Articles liés à Seeing Further: The Story of Science and the Royal...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

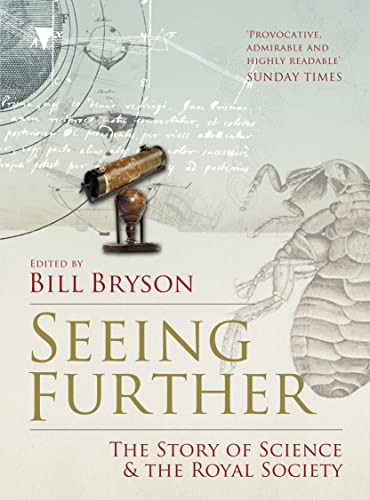

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNEdited and introduced by Bill Bryson, and with contributions from Richard Dawkins, Margaret Atwood, David Attenborough, Martin Rees and Richard Fortey amongst others, this is a remarkable volume celebrating the 350th anniversary of the Royal Society. Since its inception in 1660, the Royal Society has pioneered scientific discovery and exploration. The oldest scientific academy in existence, its backbone is its Fellowship of the most eminent scientists in history including Charles Darwin, Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein. Today, its Fellows are the most influential men and women in science, many of whom have contributed to this ground-breaking volume alongside some of the world's most celebrated novelists, essayists and historians. Published to mark its 350th anniversary, this highly illustrated book celebrates the Royal Society's vast achievements in its illustrious past as well as its huge contribution to the development of modern science.With unrestricted access to the Society's archives and photographs, 'Seeing Further' shows that the history of scientific endeavour and discovery is a continuous thread running through the history of the world and of society - and is one that continues to shape the world we live in today.

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Extrait :

1

James Gleick

At the Beginning: More Things in Heaven and Earth

James Gleick last visited the Royal Society when researching his recent biography Isaac Newton. His first book, Chaos, was a National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize finalist and an international bestseller, translated into more than twenty languages. His other books include Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman, Faster: The Acceleration of Just About Everything and What Just Happened: A Chronicle from the Information Frontier.

The first formal meeting of what became the Royal Society was held in London on 28 November 1660. The dozen men present agreed to constitute themselves as a society for ‘the promoting of experimental philosophy’. Experimental philosophy? What could that mean? As James Gleick shows from their own records, it meant, among other things, a boundless curiosity about natural phenomena of all kinds, and something else – a kind of exuberance of inquiry which has lasted into our own day.

To invent science was a heavy responsibility, which these gentlemen took seriously. Having declared their purpose to be ‘improving’ knowledge, they gathered it and they made it – two different things. From their beginnings in the winter of 1660–61, when they met with the King’s approval Wednesday afternoons in Laurence Rooke’s room at Gresham College, their way of making knowledge was mainly to talk about it.

For accumulating information in the raw, they were well situated in the place that seemed to them the centre of the universe: ‘It has a large Intercourse with all the Earth: ... a City, where all the Noises and Business in the World do meet: ... the constant place of Residence for that Knowledge, which is to be made up of the Reports and Intelligence of all Countries.’ But we who know everything tend to forget how little was known. They were starting from scratch. To the extent that the slate was not blank, it often needed erasure.

At an initial meeting on 2 January their thoughts turned to the faraway island of Tenerife, where stood the great peak known to mariners on the Atlantic trade routes and sometimes thought to be the tallest in the known world. If questions could be sent there (Ralph Greatorex, a maker of mathematical instruments with a shop in the Strand, proposed to make the voyage), what would the new and experimental philosophers want to ask? The Lord Viscount Brouncker and Robert Boyle, who was performing experiments on that invisible fluid the air, composed a list:

· ‘Try the quicksilver experiment.’ This involved a glass tube, bent into a U, partly filled with mercury, and closed at one end. Boyle believed that air had weight and ‘spring’ and that these could be measured. The height of the mercury column fluctuated, which he explained by saying, ‘there may be strange Ebbings and Flowings, as it were, in the Atmosphere’ – from causes unknown. Christopher Wren (‘that excellent Mathematician’) wondered whether this might correspond to ‘those great Flowings and Ebbs of the Sea, that they call the Spring-Tides’, since, after all, Descartes said the tides were caused by pressure made on the air by the Moon and the Intercurrent Ethereal Substance. Boyle, having spent many hours watching the mercury rise and fall unpredictably, somewhat doubted it.

· Find out whether a pendulum clock runs faster or slower at the mountain top. This was a problem, though: pendulum clocks were themselves the best measures of time. So Brouncker and Boyle suggested using an hourglass.

· Hobble birds with weights and find out whether they fly better above or below.

· ‘Observe the difference of sounds made by a bell, watch, gun, &c. on the top of the hill, in respect to the same below.’

And many more: candles, vials of smoky liquor, sheep’s bladders filled with air, pieces of iron and copper, and various living creatures, to be carried thither.

A stew of good questions, but to no avail. Greatorex apparently did not go, nor anyone else of use to the virtuosi, for the next half-century. Then, when Mr J. Edens made an expedition to the top of the peak in August 1715, he was less interested in the air than in the volcanic activity: ‘the Sulphur discharg[ing] its self like a Squib or Serpent made of Gun-powder, the Fire running downwards in a Stream, and the Smoak ascending upwards’. He did wish he had brought a Barometer – the device having by now been invented and named – but he would have had to send all the way to England, and the expense would have come from his own pocket. Nonetheless he was able to say firmly that there was no truth to the report about ‘the Difficulty of breathing upon the top of the place; for we breath’d as well as if we had been below’.

No one knew how tall the mountain was anyway, or how to measure it. Sixteenth-century estimates ranged as high as 15 leagues (more than 80,000 metres) and 70 miles (more than 110,000 metres). One method was to measure from a ship at sea; this required a number for the radius of the Earth, which wasn’t known itself, though we know that Eratosthenes had got it right. The authoritative Geographia of Bernhardus Varenius, published in Cambridge in 1672 with Isaac Newton’s help, computed the height as 8 Italian miles (11,840 metres) – ‘quae incredibilis fere est’ – and then guessed 4 to 5 miles instead. (An accurate measurement, 3,718 metres, had to wait till the twentieth century.) But interest in Tenerife did not abate – far from it. Curiosity about remote lands was always honoured in Royal Society discourse. ‘It was directed,’ according to the minutes for 25 March, ‘that inquiry should be made, whether there be such little dwarvish men in the vaults of the Canaries, as was reported.’ And at the next meeting, ‘It was ordered to inquire, whether the flakes of snow are bigger or less in Teneriffe than in England ...’

Reports did arrive from all over. The inaugural issue of the Philosophical Transactions featured a report (written by Boyle, at second hand) of ‘a very odd Monstrous Calf ’ born in Hampshire; another ‘of a peculiar Lead-Ore of Germany’; and another of ‘an Hungarian Bolus’, a sort of clay said to have good effects in physick. From Leyden came news of a man who, by star-gazing nightly in the cold, wet air, obstructed the pores of his skin, ‘which appeared hence, because that the shirt, he had worn five or six weeks, was then as white as if he had worn it but one day’. The same correspondent described a young maid, about thirteen years old, who ate salt ‘as other children doe Sugar: whence she was so dried up, and grown so stiff, that she could not stirre her limbs, and was thereby starved to death’.

Iceland was the source of especially strange rumours: holes, ‘which, if a stone be thrown into them, throw it back again’; fire in the sea, and smoking lakes, and green flames appearing on hillsides; a lake near the middle of the isle ‘that kills the birds, that fly over it’; and inhabitants that sell winds and converse with spirits. It was ordered that inquiries be sent regarding all these, as well as ‘what is said there concerning raining mice’.

The very existence of these published transactions encouraged witnesses to relay the noteworthy and strange, and who could say what was strange and what was normal? Correspondents were moved to share their ‘Observables’. Observables upon a monstrous head. Observables in the body of the Earl of Balcarres (his liver very big; the spleen big also). Observables were as ephemeral as vapour in this camera-less world, and the Society’s role was to grant them persistence. Many letters were titled simply, ‘An Account of a remarkable [object, event, appearance]’: a remarkable meteor, fossil, halo; monument unearthed, marine insect captured, ice shower endured; Aurora Borealis, Imperfection of Sight, Darkness at Detroit; appearance in the Moon, agitation of the sea; and a host of remarkable cures. An Account of a remarkable Fish began, ‘I herewith take the liberty of sending you a drawing of a very uncommon kind of fish which was lately caught in King-Road ...’

It fought violently against the fisher-man’s boat ... and was killed with great difficulty. No body here can tell what fish it is ... I took the drawing on the spot, and do wish I had had my Indian Ink and Pencils ...

From Scotland came a careful report by Robert Moray of unusual tides in the Western Isles. Moray, a confidant of the King and an earnest early member of the Society, had spent some time in a tract of islands for which he had no name – ‘called by the Inhabitants, the Long-Island’ (the Outer Hebrides, we would say now). ‘I observed a very strange Reciprocation of the Flux and Re-flux of the Sea,’ he wrote, ‘and heard of another, no less remarkable.’ He described them in painstaking detail: the number of days before the full and quarter moons; the current running sometimes eastward but other times westward; flowing from 9½ of the clock to 3½; ebbing and flowing orderly for some days, but then making ‘constantly a great and singular variation’. Tides were a Royal Society favourite, and they were a problem. Humanity had been watching them for uncounted thousands of years, and observing the coincidence of their timing with the phases of the Moon, without developing an understanding of their nature – Descartes notwithstanding. No global sense of the tides could be possibl...

Présentation de l'éditeur :

James Gleick

At the Beginning: More Things in Heaven and Earth

James Gleick last visited the Royal Society when researching his recent biography Isaac Newton. His first book, Chaos, was a National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize finalist and an international bestseller, translated into more than twenty languages. His other books include Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman, Faster: The Acceleration of Just About Everything and What Just Happened: A Chronicle from the Information Frontier.

The first formal meeting of what became the Royal Society was held in London on 28 November 1660. The dozen men present agreed to constitute themselves as a society for ‘the promoting of experimental philosophy’. Experimental philosophy? What could that mean? As James Gleick shows from their own records, it meant, among other things, a boundless curiosity about natural phenomena of all kinds, and something else – a kind of exuberance of inquiry which has lasted into our own day.

To invent science was a heavy responsibility, which these gentlemen took seriously. Having declared their purpose to be ‘improving’ knowledge, they gathered it and they made it – two different things. From their beginnings in the winter of 1660–61, when they met with the King’s approval Wednesday afternoons in Laurence Rooke’s room at Gresham College, their way of making knowledge was mainly to talk about it.

For accumulating information in the raw, they were well situated in the place that seemed to them the centre of the universe: ‘It has a large Intercourse with all the Earth: ... a City, where all the Noises and Business in the World do meet: ... the constant place of Residence for that Knowledge, which is to be made up of the Reports and Intelligence of all Countries.’ But we who know everything tend to forget how little was known. They were starting from scratch. To the extent that the slate was not blank, it often needed erasure.

At an initial meeting on 2 January their thoughts turned to the faraway island of Tenerife, where stood the great peak known to mariners on the Atlantic trade routes and sometimes thought to be the tallest in the known world. If questions could be sent there (Ralph Greatorex, a maker of mathematical instruments with a shop in the Strand, proposed to make the voyage), what would the new and experimental philosophers want to ask? The Lord Viscount Brouncker and Robert Boyle, who was performing experiments on that invisible fluid the air, composed a list:

· ‘Try the quicksilver experiment.’ This involved a glass tube, bent into a U, partly filled with mercury, and closed at one end. Boyle believed that air had weight and ‘spring’ and that these could be measured. The height of the mercury column fluctuated, which he explained by saying, ‘there may be strange Ebbings and Flowings, as it were, in the Atmosphere’ – from causes unknown. Christopher Wren (‘that excellent Mathematician’) wondered whether this might correspond to ‘those great Flowings and Ebbs of the Sea, that they call the Spring-Tides’, since, after all, Descartes said the tides were caused by pressure made on the air by the Moon and the Intercurrent Ethereal Substance. Boyle, having spent many hours watching the mercury rise and fall unpredictably, somewhat doubted it.

· Find out whether a pendulum clock runs faster or slower at the mountain top. This was a problem, though: pendulum clocks were themselves the best measures of time. So Brouncker and Boyle suggested using an hourglass.

· Hobble birds with weights and find out whether they fly better above or below.

· ‘Observe the difference of sounds made by a bell, watch, gun, &c. on the top of the hill, in respect to the same below.’

And many more: candles, vials of smoky liquor, sheep’s bladders filled with air, pieces of iron and copper, and various living creatures, to be carried thither.

A stew of good questions, but to no avail. Greatorex apparently did not go, nor anyone else of use to the virtuosi, for the next half-century. Then, when Mr J. Edens made an expedition to the top of the peak in August 1715, he was less interested in the air than in the volcanic activity: ‘the Sulphur discharg[ing] its self like a Squib or Serpent made of Gun-powder, the Fire running downwards in a Stream, and the Smoak ascending upwards’. He did wish he had brought a Barometer – the device having by now been invented and named – but he would have had to send all the way to England, and the expense would have come from his own pocket. Nonetheless he was able to say firmly that there was no truth to the report about ‘the Difficulty of breathing upon the top of the place; for we breath’d as well as if we had been below’.

No one knew how tall the mountain was anyway, or how to measure it. Sixteenth-century estimates ranged as high as 15 leagues (more than 80,000 metres) and 70 miles (more than 110,000 metres). One method was to measure from a ship at sea; this required a number for the radius of the Earth, which wasn’t known itself, though we know that Eratosthenes had got it right. The authoritative Geographia of Bernhardus Varenius, published in Cambridge in 1672 with Isaac Newton’s help, computed the height as 8 Italian miles (11,840 metres) – ‘quae incredibilis fere est’ – and then guessed 4 to 5 miles instead. (An accurate measurement, 3,718 metres, had to wait till the twentieth century.) But interest in Tenerife did not abate – far from it. Curiosity about remote lands was always honoured in Royal Society discourse. ‘It was directed,’ according to the minutes for 25 March, ‘that inquiry should be made, whether there be such little dwarvish men in the vaults of the Canaries, as was reported.’ And at the next meeting, ‘It was ordered to inquire, whether the flakes of snow are bigger or less in Teneriffe than in England ...’

Reports did arrive from all over. The inaugural issue of the Philosophical Transactions featured a report (written by Boyle, at second hand) of ‘a very odd Monstrous Calf ’ born in Hampshire; another ‘of a peculiar Lead-Ore of Germany’; and another of ‘an Hungarian Bolus’, a sort of clay said to have good effects in physick. From Leyden came news of a man who, by star-gazing nightly in the cold, wet air, obstructed the pores of his skin, ‘which appeared hence, because that the shirt, he had worn five or six weeks, was then as white as if he had worn it but one day’. The same correspondent described a young maid, about thirteen years old, who ate salt ‘as other children doe Sugar: whence she was so dried up, and grown so stiff, that she could not stirre her limbs, and was thereby starved to death’.

Iceland was the source of especially strange rumours: holes, ‘which, if a stone be thrown into them, throw it back again’; fire in the sea, and smoking lakes, and green flames appearing on hillsides; a lake near the middle of the isle ‘that kills the birds, that fly over it’; and inhabitants that sell winds and converse with spirits. It was ordered that inquiries be sent regarding all these, as well as ‘what is said there concerning raining mice’.

The very existence of these published transactions encouraged witnesses to relay the noteworthy and strange, and who could say what was strange and what was normal? Correspondents were moved to share their ‘Observables’. Observables upon a monstrous head. Observables in the body of the Earl of Balcarres (his liver very big; the spleen big also). Observables were as ephemeral as vapour in this camera-less world, and the Society’s role was to grant them persistence. Many letters were titled simply, ‘An Account of a remarkable [object, event, appearance]’: a remarkable meteor, fossil, halo; monument unearthed, marine insect captured, ice shower endured; Aurora Borealis, Imperfection of Sight, Darkness at Detroit; appearance in the Moon, agitation of the sea; and a host of remarkable cures. An Account of a remarkable Fish began, ‘I herewith take the liberty of sending you a drawing of a very uncommon kind of fish which was lately caught in King-Road ...’

It fought violently against the fisher-man’s boat ... and was killed with great difficulty. No body here can tell what fish it is ... I took the drawing on the spot, and do wish I had had my Indian Ink and Pencils ...

From Scotland came a careful report by Robert Moray of unusual tides in the Western Isles. Moray, a confidant of the King and an earnest early member of the Society, had spent some time in a tract of islands for which he had no name – ‘called by the Inhabitants, the Long-Island’ (the Outer Hebrides, we would say now). ‘I observed a very strange Reciprocation of the Flux and Re-flux of the Sea,’ he wrote, ‘and heard of another, no less remarkable.’ He described them in painstaking detail: the number of days before the full and quarter moons; the current running sometimes eastward but other times westward; flowing from 9½ of the clock to 3½; ebbing and flowing orderly for some days, but then making ‘constantly a great and singular variation’. Tides were a Royal Society favourite, and they were a problem. Humanity had been watching them for uncounted thousands of years, and observing the coincidence of their timing with the phases of the Moon, without developing an understanding of their nature – Descartes notwithstanding. No global sense of the tides could be possibl...

From the Royal Society, a peerless collection of all-new science writing

Bill Bryson, who explored all - or at least a great deal of - current scientific knowledge in A Short History of Nearly Everything, now turns his attention to the history of that knowledge. As editor of Seeing Further, he has rounded up an extraordinary roster of scientists who write and writers who know science in order to celebrate 350 years of the Royal Society, Britain's scientific national academy. The result is an encyclopedic survey of the history, philosophy and current state of science, written in an accessible and inspiring style by some of today's most important writers.

The contributors include Margaret Atwood, Steve Jones, Richard Dawkins, James Gleick, Richard Holmes, and Neal Stephenson, among many others, on subjects ranging from metaphysics to nuclear physics, from the threatened endtimes of flu and climate change to our evolving ideas about the nature of time itself, from the hidden mathematics that rule the universe to the cosmological principle that guides Star Trek.

The collection begins with a brilliant introduction from Bryson himself, who says: "It is impossible to list all the ways that the Royal Society has influenced the world, but you can get some idea by typing in 'Royal Society' as a word search in the electronic version of the Dictionary of National Biography. That produces 218 pages of results — 4,355 entries, nearly as many as for the Church of England (at 4,500) and considerably more than for the House of Commons (3,124) or House of Lords (2,503)."

As this book shows, the Royal Society not only produces the best scientists and science, it also produces and inspires the very best science writing.

Bill Bryson, who explored all - or at least a great deal of - current scientific knowledge in A Short History of Nearly Everything, now turns his attention to the history of that knowledge. As editor of Seeing Further, he has rounded up an extraordinary roster of scientists who write and writers who know science in order to celebrate 350 years of the Royal Society, Britain's scientific national academy. The result is an encyclopedic survey of the history, philosophy and current state of science, written in an accessible and inspiring style by some of today's most important writers.

The contributors include Margaret Atwood, Steve Jones, Richard Dawkins, James Gleick, Richard Holmes, and Neal Stephenson, among many others, on subjects ranging from metaphysics to nuclear physics, from the threatened endtimes of flu and climate change to our evolving ideas about the nature of time itself, from the hidden mathematics that rule the universe to the cosmological principle that guides Star Trek.

The collection begins with a brilliant introduction from Bryson himself, who says: "It is impossible to list all the ways that the Royal Society has influenced the world, but you can get some idea by typing in 'Royal Society' as a word search in the electronic version of the Dictionary of National Biography. That produces 218 pages of results — 4,355 entries, nearly as many as for the Church of England (at 4,500) and considerably more than for the House of Commons (3,124) or House of Lords (2,503)."

As this book shows, the Royal Society not only produces the best scientists and science, it also produces and inspires the very best science writing.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurWilliam Collins

- Date d'édition2011

- ISBN 10 0007302576

- ISBN 13 9780007302574

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages496

- ÉditeurBryson Bill

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 38,28

Frais de port :

EUR 3,73

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Seeing Further

Edité par

Harper Collins Publishers

(2011)

ISBN 10 : 0007302576

ISBN 13 : 9780007302574

Neuf

Couverture souple

Quantité disponible : 4

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Etat : New. pp. 496. N° de réf. du vendeur 2614281315

Acheter neuf

EUR 38,28

Autre devise

Seeing Further

Edité par

Harper Collins Publishers

(2011)

ISBN 10 : 0007302576

ISBN 13 : 9780007302574

Neuf

Couverture souple

Quantité disponible : 4

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Etat : New. pp. 496. N° de réf. du vendeur 11425212

Acheter neuf

EUR 36,04

Autre devise

Seeing Further: The Story of Science and the Royal Society

Edité par

Harper Press

(2011)

ISBN 10 : 0007302576

ISBN 13 : 9780007302574

Neuf

Brossura

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Brossura. Etat : nuovo. N° de réf. du vendeur 069408

Acheter neuf

EUR 28,50

Autre devise