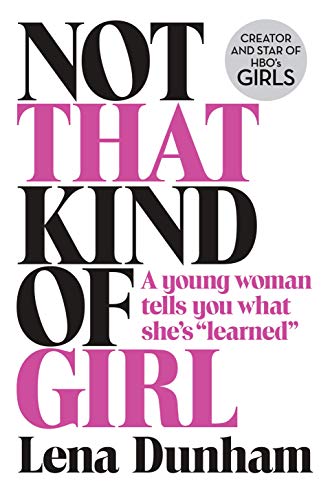

Articles liés à Not That Kind of Girl: A Young Woman Tells You What...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBN

Extrait :

Little Leather Gloves

The Joy of Wasting Time

I remember when my schedule was as flexible as she is.

—-Drake

I worked at the baby store for nine months.

Just recently graduated, I had stormed out of my restaurant job on a whim, causing my father to yell, “You can’t just do that! What if you had children?”

“Well, thank God I don’t!” I yelled right back.

At this point, I was living in a glorified closet at the back of my parents’ loft, a room they had assigned me because they thought I would graduate and move out like a properly evolving person. The room had no windows, and so, in order to get a glimpse of daylight, I had to slide open the door to my sister’s bright, airy room. “Go away,” she would hiss.

I was unemployed. And while I had a roof over my head (my parents’) and food to eat (also technically theirs), my days were shapeless, and the disappointment of the people who loved me (my parents) was palpable. I slept until noon, became defensive when asked about my plans for the future, and gained weight like it was a viable profession. I was becoming the kind of adult parents worry about producing.

I had been ambitious once. In college, all I seemed to do was found literary magazines with inexplicable names and stage experimental black--box theater and join teams (rugby, if only for a day or so). I was eager and hungry: for new art, for new friendship, for sex. Despite my ambivalence about academia, college was a wonderful gig, thousands of hours to tend to yourself like a garden. But now I was back to zero. No grades. No semesters. No CliffsNotes in case of emergency. I was lost.

It’s not that I didn’t have plans. Oh, I had plans. Just none that these small minds could understand. My first idea was to be the assistant to a private eye. I was always being accused of extreme nosiness, so why not turn this character flaw into cold hard cash? After hunting around on Craigslist, however, it soon became clear that most private eyes worked alone—-or if they needed an assistant, they wanted someone with the kind of sensual looks to bait cheating husbands. The second idea was baker. After all, I love bread and all bread by--products. But no, that involved waking up at four every morning. And knowing how to bake. What about preschool art teacher? Turns out that involved more than just a passion for pasta necklaces. There would be no rom--com--ready job for me.

The only silver lining in my situation was that it allowed me to reconnect with my oldest friends, Isabel and Joana. We were all back in Tribeca, the same neighborhood where we had met in preschool. Isabel was finishing her sculpture degree, living with an aging pug named Hamlet who had once had his head run over by a truck and survived. Joana had just completed art school and was sporting the festive remains of a bleached mullet. I had broken up with the hippie boyfriend I considered my bridge to health and wholeness and was editing a “feature film” on my laptop. Isabel was living in her father’s old studio, which she had decorated with found objects, standing racks of children’s Halloween costumes, and a TV from 1997. When the three of us met there to catch up, Joana’s nails painted like weed leaves and Monets, I felt at peace.

Isabel was employed at Peach and the Babke, a high--end children’s clothing store in our neighborhood. Isabel is a true eccentric—-not the self--conscious kind who collects feathers and snow globes but the kind whose passions and predilections are so genuinely out of sync with the world at large that she herself becomes an object of fascination. One day Isabel had strolled into the store on a dare to inquire about employment, essentially because it was the funniest thing she could imagine doing for a living. Wearing kneesocks and a man’s shirt as a dress, she had been somewhat dismayed when she was offered a job on the spot. Joana joined her there a few weeks later, when the madness of the yearly sample sale required extra hands.

“It’s a ball,” said Isabel.

“I mean, it’s awfully easy,” said Joana.

Peach and the Babke sold baby clothes at such a high price point that customers would often laugh out loud upon glimpsing a tag. Cashmere cardigans, ratty tutus, and fine--wale cords, sized six months to eight years. This is where you came if you wanted your daughter to look like a Dorothea Lange photo or your son to resemble a jaunty old--time train conductor, all oversize overalls and perky wool caps. It will be a miracle if any of the boys who wore Peach and the Babke emerged from childhood able to maintain an erection.

We often spent Isabel’s lunch break in Pecan, a local coffee bar where we disturbed yuppies on laptops with our incessant—-and filthy—-chatter.

“I can’t find a goddamn fucking job and I’m too fat to be a stripper,” I said as I polished off a stale croissant.

Isabel paused as if contemplating an advanced theorem, then lit up. “We need another girl at Peach! We do, we do, we do!” It would be a gas, she told me. It’d be like our own secret clubhouse. “You can get tons of free ribbons!” It was such an easy job. All you had to do was fold, wrap, and minister to the rich and famous. “That’s all we did as kids, be nice to art collectors so our parents could pay our tuition,” Isabel said. “You’ll be amazing at it.”

The next day, I stopped by with a copy of my résumé and met Phoebe, the manager of the store, who looked like the saddest fourth--grader you ever met but was, in reality, thirty--two and none too pleased about it. She was beautiful like a Gibson girl, a pale round face, heavy lids, and rosy lips. She wiped her hands on her plaid pinafore.

“Why did you leave your last job?” she asked.

“I was hooking up with someone in the kitchen and the dessert chef was a bitch,” I explained.

“I can pay you one hundred dollars a day, cash,” she said.

“Sounds good.” I was secretly thrilled, both at the salary and the prospect of spending every day with my oldest and most amusing friends.

“We also buy you lunch every day,” Phoebe said.

“The lunch is awesome!” Isabel chimed in, spreading some pint--sized leather gloves that retailed for $155 out in the display case next to a broken vintage camera (price upon request).

“I’m in,” I said. For reasons I will never understand but did not question, Phoebe handed me twenty--five dollars for the interview itself.

And with that, Peach and the Babke became the most poorly staffed store in the history of the world.

The days at Peach and the Babke followed a certain rhythm. With only one window up front, it was hard to get a sense of time passing, and so life became a sedentary, if pleasant, mass of risotto and tiny overalls. But I will reconstruct it for you as best as I can:

10:10 Roll in the door with a coffee in your hand. If you’re feeling nice, you also bring one for Phoebe. “Sorry I’m late,” you say before flinging your coat on the floor.

10:40 Head into the back room to start casually folding some pima--cotton baby leggings ($55 to $65) and roll--neck fisherman sweaters ($175).

10:50 Get distracted telling Joana a story about a homeless guy you saw wearing a salad spinner as a hat.

11:10 First customer rings the bell. They are either freezing and looking to browse before their next appointment or obscenely rich and about to purchase five thousand dollars’ worth of gifts for their nieces. You and Joana try to do the best wrapping job you can and to calculate the tax properly, but there is a good chance you charged them an extra five hundred dollars.

11:15 Start talking about lunch. How badly you want or don’t want it. How good it will be when it finally hits your lips or, alternately, how little mind you even pay to food these days.

11:25 Call next door for the specials.

12:00 Isabel arrives. She is on a schedule called Princess Hours. When you ask if you can also work Princess Hours, Phoebe says, “No, they’re for princesses.”

12:30 Sit down for an elaborate three--course meal. Let Phoebe try your couscous, since it’s the least you can do. Split a baguette with Isabel if you can have half her butternut squash soup. Eat a pot of fresh ricotta to finish it off.

1:00 Joana leaves for therapy.

1:30 The UPS guy comes and unloads boxes of rag dolls made of vintage curtains ($320). You ask him how his son is doing. He says he’s in jail.

2:00 Isabel leaves for therapy.

2:30 Meg Ryan comes in wearing a large hat, buys nothing.

3:00 Phoebe asks you to rub her head for a while. She lies on the rug in the back and moans with pleasure. A customer rings the doorbell. She says to ignore it, and when her massage is done she sends you around the corner for cappuccino and brownies.

4:00 You leave for therapy, collecting your hundred dollars.

6:00 This is the time work was actually supposed to end, but you are already home, half asleep, waiting for Jeff Ruiz to finish his landscaping job and meet you on the roof of his building to drink beer and feel each other up. Only once in nine months does Phoebe admonish you for your poor work ethic, and she feels so guilty about it that at lunch she goes across the street and buys you a scented candle.

Phoebe ran the store with her mother, Linda, though Linda spent most of her time in Pennsylvania or, if she was in the city, upstairs in the apartment she kept, smoking and eating popcorn from a big metal bowl. As thoughtful and conflicted as Phoebe was, her mother was so wild her hair stood on end. Phoebe handled the practicalities of the business, while Linda conceived designs so fantastical that rather than sketch them she would just wave ribbons and scraps in the air, outlining a sweater or a tutu. Phoebe and Linda’s fights had a tendency to turn rabid and ranged from small--business issues to the very fiber of their characters.

“All my friends were getting abortions!” she screamed. Linda often spoke of her former life in San Francisco, prechildren, a utopia of knitwear designers and early Western practitioners of yoga who supported and inspired one another. The money was good, and the sex was even better.

As they fought, Isabel and I (or Joana and I, as it was rare we all worked at once) would look at each other nervously, shrug, then proceed to try on all the dresses we carried in a child’s size 8, whose hemlines hit right below our crotches (aka just right). Another common distraction was to cover our heads in rabbit--fur barrettes ($16) or strap each other up with ribbons like some ersatz Helmut Newton photograph.

Sometimes I would find Phoebe crying by the air conditioner, head on the desk where she kept her old PC, staring at a pile of unpaid bills. The fact was the store was in trouble. The recession was in full swing and, in times of economic hardship, high--end children’s clothing is the first thing to go. We felt a deep and impenetrable sadness when we watched a hip--hop mogul’s credit card get declined, a sure sign of doom for Peach and the Babke—-and for the world.

Every day we hoped for a big sale, and every day we watched Phoebe’s brow furrow as she went over the books, and every night we took our one--hundred--dollar bill home without reservation.

The job allowed us a lot of time for socializing. Together we were finding our own New York, which looked a lot like the New York of our parents. We went to art openings for the free wine and Christmas parties for the free food, then peeled off to smoke pot on Isabel’s couch and watch reruns of Seinfeld. We stopped by parties where we didn’t know the host, wore skirts as tube tops and tights as pants. We split bowls of Bo-lo-gnese at chic restaurants rather than get full meals at boring ones. A night of carousing never passed without me stepping outside the experience to think, Yes, this must be what it is to be young.

Upon graduation I had felt a heavy sense of doom, a sense that nothing would ever be simple again. But look, look what we had found! We were making it work, with our cash and our bad wrapping jobs, with our fried overdyed hair and our fried overprocessed foods. Everything took on a hazy romance: having a pimple, eating a doughnut, being cold. Nothing was a tragedy, and everything was a joke. I had waited a long time to be a woman, a long time to venture away from my parents, and now I had sex, once with two guys in a week, and bragged about it like a divorcée who was getting back in the game. Up to my knees in mud from a night on the town, I rinsed off in the shower as Isabel watched and said, “Handle it, dirty girl!”

I didn’t know the word for it, but I was happy. I was happy wrapping presents, catering to listless bankers’ wives, and locking the store up with a rusty key a few minutes before closing time. I was happy being slightly condescending to people with platinum cards, reveling in our status as shopgirls who knew more than we were letting on. We would stay here in our cave, looking out on Tribeca through the picture window, and on weekends we would trip up the West Side Highway in red dresses, sloshing beer, ready to fuck and fight and fall asleep on top of one another.

But ambition is a funny thing: it creeps in when you least expect it and keeps you moving, even when you think you want to stay put. I missed making things, the meaning it gave this long march we call life. One night, as we readied ourselves for another event where we weren’t exactly welcome, it occurred to me: This is something. Why didn’t we tell this story, instead of just living it? The story of children of the art world trying (and failing) to match their parents’ successes, unsure of their own passions, but sure they wanted glory. Why didn’t we make a webseries (at that point, the Internet webseries was poised to replace film, television, radio, and literature) about characters even more pathetic than we were?

We never made it to the party that night. Instead we ordered pizza, curled up in easy chairs, and began pitching names and locations and plotlines into the night. We ransacked Isabel’s closet for possible costume pieces (a beaded flapper dress, a Dudley Do--Right hat), and Joana conceived the hairstyle that would be her character’s signature (a sleek beehive built around a shampoo bottle for height). And so, using the money that Peach and the Babke provided, we began to create something that would reflect the manic energy of this moment.

It was called Delusional Downtown Divas, a title we hated but couldn’t top. Isabel portrayed AgNess, an aspiring businesswoman with a passion for power suits. Joana was the enigmatic Swann, a private performance artist. My character, Oona Winegrod, was an aspiring novelist who had never actually written a word. All of them were obsessed with a young painter named Jake Pheasant. We completed ten episodes, many of which featured cameos from our parents’ friends, who still viewed us as children doing an adorable class project.

Looking at the videos now, they leave something to be desired. Blaringly digital, with shaky camerawork, we careen across the screen in messy costumes, cracking up at our own jokes, tickled wi...

Revue de presse :

The Joy of Wasting Time

I remember when my schedule was as flexible as she is.

—-Drake

I worked at the baby store for nine months.

Just recently graduated, I had stormed out of my restaurant job on a whim, causing my father to yell, “You can’t just do that! What if you had children?”

“Well, thank God I don’t!” I yelled right back.

At this point, I was living in a glorified closet at the back of my parents’ loft, a room they had assigned me because they thought I would graduate and move out like a properly evolving person. The room had no windows, and so, in order to get a glimpse of daylight, I had to slide open the door to my sister’s bright, airy room. “Go away,” she would hiss.

I was unemployed. And while I had a roof over my head (my parents’) and food to eat (also technically theirs), my days were shapeless, and the disappointment of the people who loved me (my parents) was palpable. I slept until noon, became defensive when asked about my plans for the future, and gained weight like it was a viable profession. I was becoming the kind of adult parents worry about producing.

I had been ambitious once. In college, all I seemed to do was found literary magazines with inexplicable names and stage experimental black--box theater and join teams (rugby, if only for a day or so). I was eager and hungry: for new art, for new friendship, for sex. Despite my ambivalence about academia, college was a wonderful gig, thousands of hours to tend to yourself like a garden. But now I was back to zero. No grades. No semesters. No CliffsNotes in case of emergency. I was lost.

It’s not that I didn’t have plans. Oh, I had plans. Just none that these small minds could understand. My first idea was to be the assistant to a private eye. I was always being accused of extreme nosiness, so why not turn this character flaw into cold hard cash? After hunting around on Craigslist, however, it soon became clear that most private eyes worked alone—-or if they needed an assistant, they wanted someone with the kind of sensual looks to bait cheating husbands. The second idea was baker. After all, I love bread and all bread by--products. But no, that involved waking up at four every morning. And knowing how to bake. What about preschool art teacher? Turns out that involved more than just a passion for pasta necklaces. There would be no rom--com--ready job for me.

The only silver lining in my situation was that it allowed me to reconnect with my oldest friends, Isabel and Joana. We were all back in Tribeca, the same neighborhood where we had met in preschool. Isabel was finishing her sculpture degree, living with an aging pug named Hamlet who had once had his head run over by a truck and survived. Joana had just completed art school and was sporting the festive remains of a bleached mullet. I had broken up with the hippie boyfriend I considered my bridge to health and wholeness and was editing a “feature film” on my laptop. Isabel was living in her father’s old studio, which she had decorated with found objects, standing racks of children’s Halloween costumes, and a TV from 1997. When the three of us met there to catch up, Joana’s nails painted like weed leaves and Monets, I felt at peace.

Isabel was employed at Peach and the Babke, a high--end children’s clothing store in our neighborhood. Isabel is a true eccentric—-not the self--conscious kind who collects feathers and snow globes but the kind whose passions and predilections are so genuinely out of sync with the world at large that she herself becomes an object of fascination. One day Isabel had strolled into the store on a dare to inquire about employment, essentially because it was the funniest thing she could imagine doing for a living. Wearing kneesocks and a man’s shirt as a dress, she had been somewhat dismayed when she was offered a job on the spot. Joana joined her there a few weeks later, when the madness of the yearly sample sale required extra hands.

“It’s a ball,” said Isabel.

“I mean, it’s awfully easy,” said Joana.

Peach and the Babke sold baby clothes at such a high price point that customers would often laugh out loud upon glimpsing a tag. Cashmere cardigans, ratty tutus, and fine--wale cords, sized six months to eight years. This is where you came if you wanted your daughter to look like a Dorothea Lange photo or your son to resemble a jaunty old--time train conductor, all oversize overalls and perky wool caps. It will be a miracle if any of the boys who wore Peach and the Babke emerged from childhood able to maintain an erection.

We often spent Isabel’s lunch break in Pecan, a local coffee bar where we disturbed yuppies on laptops with our incessant—-and filthy—-chatter.

“I can’t find a goddamn fucking job and I’m too fat to be a stripper,” I said as I polished off a stale croissant.

Isabel paused as if contemplating an advanced theorem, then lit up. “We need another girl at Peach! We do, we do, we do!” It would be a gas, she told me. It’d be like our own secret clubhouse. “You can get tons of free ribbons!” It was such an easy job. All you had to do was fold, wrap, and minister to the rich and famous. “That’s all we did as kids, be nice to art collectors so our parents could pay our tuition,” Isabel said. “You’ll be amazing at it.”

The next day, I stopped by with a copy of my résumé and met Phoebe, the manager of the store, who looked like the saddest fourth--grader you ever met but was, in reality, thirty--two and none too pleased about it. She was beautiful like a Gibson girl, a pale round face, heavy lids, and rosy lips. She wiped her hands on her plaid pinafore.

“Why did you leave your last job?” she asked.

“I was hooking up with someone in the kitchen and the dessert chef was a bitch,” I explained.

“I can pay you one hundred dollars a day, cash,” she said.

“Sounds good.” I was secretly thrilled, both at the salary and the prospect of spending every day with my oldest and most amusing friends.

“We also buy you lunch every day,” Phoebe said.

“The lunch is awesome!” Isabel chimed in, spreading some pint--sized leather gloves that retailed for $155 out in the display case next to a broken vintage camera (price upon request).

“I’m in,” I said. For reasons I will never understand but did not question, Phoebe handed me twenty--five dollars for the interview itself.

And with that, Peach and the Babke became the most poorly staffed store in the history of the world.

The days at Peach and the Babke followed a certain rhythm. With only one window up front, it was hard to get a sense of time passing, and so life became a sedentary, if pleasant, mass of risotto and tiny overalls. But I will reconstruct it for you as best as I can:

10:10 Roll in the door with a coffee in your hand. If you’re feeling nice, you also bring one for Phoebe. “Sorry I’m late,” you say before flinging your coat on the floor.

10:40 Head into the back room to start casually folding some pima--cotton baby leggings ($55 to $65) and roll--neck fisherman sweaters ($175).

10:50 Get distracted telling Joana a story about a homeless guy you saw wearing a salad spinner as a hat.

11:10 First customer rings the bell. They are either freezing and looking to browse before their next appointment or obscenely rich and about to purchase five thousand dollars’ worth of gifts for their nieces. You and Joana try to do the best wrapping job you can and to calculate the tax properly, but there is a good chance you charged them an extra five hundred dollars.

11:15 Start talking about lunch. How badly you want or don’t want it. How good it will be when it finally hits your lips or, alternately, how little mind you even pay to food these days.

11:25 Call next door for the specials.

12:00 Isabel arrives. She is on a schedule called Princess Hours. When you ask if you can also work Princess Hours, Phoebe says, “No, they’re for princesses.”

12:30 Sit down for an elaborate three--course meal. Let Phoebe try your couscous, since it’s the least you can do. Split a baguette with Isabel if you can have half her butternut squash soup. Eat a pot of fresh ricotta to finish it off.

1:00 Joana leaves for therapy.

1:30 The UPS guy comes and unloads boxes of rag dolls made of vintage curtains ($320). You ask him how his son is doing. He says he’s in jail.

2:00 Isabel leaves for therapy.

2:30 Meg Ryan comes in wearing a large hat, buys nothing.

3:00 Phoebe asks you to rub her head for a while. She lies on the rug in the back and moans with pleasure. A customer rings the doorbell. She says to ignore it, and when her massage is done she sends you around the corner for cappuccino and brownies.

4:00 You leave for therapy, collecting your hundred dollars.

6:00 This is the time work was actually supposed to end, but you are already home, half asleep, waiting for Jeff Ruiz to finish his landscaping job and meet you on the roof of his building to drink beer and feel each other up. Only once in nine months does Phoebe admonish you for your poor work ethic, and she feels so guilty about it that at lunch she goes across the street and buys you a scented candle.

Phoebe ran the store with her mother, Linda, though Linda spent most of her time in Pennsylvania or, if she was in the city, upstairs in the apartment she kept, smoking and eating popcorn from a big metal bowl. As thoughtful and conflicted as Phoebe was, her mother was so wild her hair stood on end. Phoebe handled the practicalities of the business, while Linda conceived designs so fantastical that rather than sketch them she would just wave ribbons and scraps in the air, outlining a sweater or a tutu. Phoebe and Linda’s fights had a tendency to turn rabid and ranged from small--business issues to the very fiber of their characters.

“All my friends were getting abortions!” she screamed. Linda often spoke of her former life in San Francisco, prechildren, a utopia of knitwear designers and early Western practitioners of yoga who supported and inspired one another. The money was good, and the sex was even better.

As they fought, Isabel and I (or Joana and I, as it was rare we all worked at once) would look at each other nervously, shrug, then proceed to try on all the dresses we carried in a child’s size 8, whose hemlines hit right below our crotches (aka just right). Another common distraction was to cover our heads in rabbit--fur barrettes ($16) or strap each other up with ribbons like some ersatz Helmut Newton photograph.

Sometimes I would find Phoebe crying by the air conditioner, head on the desk where she kept her old PC, staring at a pile of unpaid bills. The fact was the store was in trouble. The recession was in full swing and, in times of economic hardship, high--end children’s clothing is the first thing to go. We felt a deep and impenetrable sadness when we watched a hip--hop mogul’s credit card get declined, a sure sign of doom for Peach and the Babke—-and for the world.

Every day we hoped for a big sale, and every day we watched Phoebe’s brow furrow as she went over the books, and every night we took our one--hundred--dollar bill home without reservation.

The job allowed us a lot of time for socializing. Together we were finding our own New York, which looked a lot like the New York of our parents. We went to art openings for the free wine and Christmas parties for the free food, then peeled off to smoke pot on Isabel’s couch and watch reruns of Seinfeld. We stopped by parties where we didn’t know the host, wore skirts as tube tops and tights as pants. We split bowls of Bo-lo-gnese at chic restaurants rather than get full meals at boring ones. A night of carousing never passed without me stepping outside the experience to think, Yes, this must be what it is to be young.

Upon graduation I had felt a heavy sense of doom, a sense that nothing would ever be simple again. But look, look what we had found! We were making it work, with our cash and our bad wrapping jobs, with our fried overdyed hair and our fried overprocessed foods. Everything took on a hazy romance: having a pimple, eating a doughnut, being cold. Nothing was a tragedy, and everything was a joke. I had waited a long time to be a woman, a long time to venture away from my parents, and now I had sex, once with two guys in a week, and bragged about it like a divorcée who was getting back in the game. Up to my knees in mud from a night on the town, I rinsed off in the shower as Isabel watched and said, “Handle it, dirty girl!”

I didn’t know the word for it, but I was happy. I was happy wrapping presents, catering to listless bankers’ wives, and locking the store up with a rusty key a few minutes before closing time. I was happy being slightly condescending to people with platinum cards, reveling in our status as shopgirls who knew more than we were letting on. We would stay here in our cave, looking out on Tribeca through the picture window, and on weekends we would trip up the West Side Highway in red dresses, sloshing beer, ready to fuck and fight and fall asleep on top of one another.

But ambition is a funny thing: it creeps in when you least expect it and keeps you moving, even when you think you want to stay put. I missed making things, the meaning it gave this long march we call life. One night, as we readied ourselves for another event where we weren’t exactly welcome, it occurred to me: This is something. Why didn’t we tell this story, instead of just living it? The story of children of the art world trying (and failing) to match their parents’ successes, unsure of their own passions, but sure they wanted glory. Why didn’t we make a webseries (at that point, the Internet webseries was poised to replace film, television, radio, and literature) about characters even more pathetic than we were?

We never made it to the party that night. Instead we ordered pizza, curled up in easy chairs, and began pitching names and locations and plotlines into the night. We ransacked Isabel’s closet for possible costume pieces (a beaded flapper dress, a Dudley Do--Right hat), and Joana conceived the hairstyle that would be her character’s signature (a sleek beehive built around a shampoo bottle for height). And so, using the money that Peach and the Babke provided, we began to create something that would reflect the manic energy of this moment.

It was called Delusional Downtown Divas, a title we hated but couldn’t top. Isabel portrayed AgNess, an aspiring businesswoman with a passion for power suits. Joana was the enigmatic Swann, a private performance artist. My character, Oona Winegrod, was an aspiring novelist who had never actually written a word. All of them were obsessed with a young painter named Jake Pheasant. We completed ten episodes, many of which featured cameos from our parents’ friends, who still viewed us as children doing an adorable class project.

Looking at the videos now, they leave something to be desired. Blaringly digital, with shaky camerawork, we careen across the screen in messy costumes, cracking up at our own jokes, tickled wi...

“The gifted [Lena] Dunham not only writes with observant precision, but also brings a measure of perspective, nostalgia and an older person’s sort of wisdom to her portrait of her (not all that much) younger self and her world. . . . As acute and heartfelt as it is funny.”—Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

“It’s not Lena Dunham’s candor that makes me gasp. Rather, it’s her writing—which is full of surprises where you least expect them. A fine, subversive book.”—David Sedaris

“This book should be required reading for anyone who thinks they understand the experience of being a young woman in our culture. I thought I knew the author rather well, and I found many (not altogether welcome) surprises.”—Carroll Dunham

“Witty, illuminating, maddening, bracingly bleak . . . [Dunham] is a genuine artist, and a disturber of the order.”—The Atlantic

“As [Lena] Dunham proves beyond a shadow of a doubt in Not That Kind of Girl, she’s not remotely at risk of offering up the same old sentimental tales we’ve read dozens of times. Dunham’s outer and inner worlds are so eccentric and distinct that every anecdote, every observation, every mundane moment of self-doubt actually feels valuable and revelatory.”—The Los Angeles Review of Books

“We are forever in search of someone who will speak not only to us but for us. . . . Not That Kind of Girl is from that kind of girl: gutsy, audacious, willing to stand up and shout. And that is why Dunham is not only a voice who deserves to be heard but also one who will inspire other important voices to tell their stories too.”—Roxane Gay, Time

“I’m surprised by how successful this was. I couldn’t finish it.”—Laurie Simmons

“Always funny, sometimes wrenching, these essays are a testament to the creative wonder that is Lena Dunham.”—Judy Blume

“An offbeat and soulful declaration that Ms. Dunham can deliver on nearly any platform she chooses.”—Dwight Garner, The New York Times

“Very few women have become famous for being who they actually are, nuanced and imperfect. When honesty happens, it’s usually couched in self-ridicule or self-help. Dunham doesn’t apologize like that—she simply tells her story as if it might be interesting. The result is shocking and radical because it is utterly familiar. Not That Kind of Girl is hilarious, artful, and staggeringly intimate; I read it shivering with recognition.”—Miranda July

“Dunham’s writing is just as smart, honest, sophisticated, dangerous, luminous, and charming as her work on Girls. Reading her makes you glad to be in the world, and glad that she’s in it with you.”—George Saunders

“A lovely, touching, surprisingly sentimental portrait of a woman who, despite repeatedly baring her body and soul to audiences, remains a bit of an enigma: a young woman who sets the agenda, defies classification and seems utterly at home in her own skin.”—Chicago Tribune

“A lot of us fear we don’t measure up beautywise and that we endure too much crummy treatment from men. On these topics, Dunham is funny, wise, and, yes, brave. . . . Among Dunham’s gifts to womankind is her frontline example that some asshole may call you undesirable or worse, and it won’t kill you. Your version matters more.”—Elle

“[Not That Kind of Girl is] witty and wise and rife with the kind of pacing and comedic flourishes that characterize early Woody Allen books. . . . Dunham is an extraordinary talent, and her vision . . . is stunningly original.”—Meghan Daum, The New York Times Magazine

“There’s a lot of power in retelling your mistakes so people can see what’s funny about them—and so that you are in control. Dunham knows about this power, and she has harnessed it.”—The Washington Post

“Dunham’s book is one of those rare examples when something hyped deserves its buzz. Those of us familiar with her wit and weirdness on HBO’s Girls will experience it in spades in these essays. . . . There are hilarious moments here—I cracked up on a crowded subway reading an essay about her childhood—and disturbing ones, too. But it’s always heartfelt and very real.”—New York Post

“We are comforted, we are charmed, we leave more empowered than we came.”—NPR

“Touching, at times profound, and deeply funny . . . Dunham is expert at combining despair and humor.”—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Most of us live our lives desperately trying to conceal the anguishing gap between our polished, aspirational, representational selves and our real, human, deeply flawed selves. Dunham lives hers in that gap, welcomes the rest of the world into it with boundless openheartedness, and writes about it with the kind of profound self-awareness and self-compassion that invite us to inhabit our own gaps and maybe even embrace them a little bit more, anguish over them a little bit less.”—Maria Popova, Brain Pickings

“Reading this book is a pleasure. . . . [These essays] exude brilliance and insight well beyond Dunham’s twenty-eight years.”—The Philadelphia Inquirer

From the Hardcover edition.

“It’s not Lena Dunham’s candor that makes me gasp. Rather, it’s her writing—which is full of surprises where you least expect them. A fine, subversive book.”—David Sedaris

“This book should be required reading for anyone who thinks they understand the experience of being a young woman in our culture. I thought I knew the author rather well, and I found many (not altogether welcome) surprises.”—Carroll Dunham

“Witty, illuminating, maddening, bracingly bleak . . . [Dunham] is a genuine artist, and a disturber of the order.”—The Atlantic

“As [Lena] Dunham proves beyond a shadow of a doubt in Not That Kind of Girl, she’s not remotely at risk of offering up the same old sentimental tales we’ve read dozens of times. Dunham’s outer and inner worlds are so eccentric and distinct that every anecdote, every observation, every mundane moment of self-doubt actually feels valuable and revelatory.”—The Los Angeles Review of Books

“We are forever in search of someone who will speak not only to us but for us. . . . Not That Kind of Girl is from that kind of girl: gutsy, audacious, willing to stand up and shout. And that is why Dunham is not only a voice who deserves to be heard but also one who will inspire other important voices to tell their stories too.”—Roxane Gay, Time

“I’m surprised by how successful this was. I couldn’t finish it.”—Laurie Simmons

“Always funny, sometimes wrenching, these essays are a testament to the creative wonder that is Lena Dunham.”—Judy Blume

“An offbeat and soulful declaration that Ms. Dunham can deliver on nearly any platform she chooses.”—Dwight Garner, The New York Times

“Very few women have become famous for being who they actually are, nuanced and imperfect. When honesty happens, it’s usually couched in self-ridicule or self-help. Dunham doesn’t apologize like that—she simply tells her story as if it might be interesting. The result is shocking and radical because it is utterly familiar. Not That Kind of Girl is hilarious, artful, and staggeringly intimate; I read it shivering with recognition.”—Miranda July

“Dunham’s writing is just as smart, honest, sophisticated, dangerous, luminous, and charming as her work on Girls. Reading her makes you glad to be in the world, and glad that she’s in it with you.”—George Saunders

“A lovely, touching, surprisingly sentimental portrait of a woman who, despite repeatedly baring her body and soul to audiences, remains a bit of an enigma: a young woman who sets the agenda, defies classification and seems utterly at home in her own skin.”—Chicago Tribune

“A lot of us fear we don’t measure up beautywise and that we endure too much crummy treatment from men. On these topics, Dunham is funny, wise, and, yes, brave. . . . Among Dunham’s gifts to womankind is her frontline example that some asshole may call you undesirable or worse, and it won’t kill you. Your version matters more.”—Elle

“[Not That Kind of Girl is] witty and wise and rife with the kind of pacing and comedic flourishes that characterize early Woody Allen books. . . . Dunham is an extraordinary talent, and her vision . . . is stunningly original.”—Meghan Daum, The New York Times Magazine

“There’s a lot of power in retelling your mistakes so people can see what’s funny about them—and so that you are in control. Dunham knows about this power, and she has harnessed it.”—The Washington Post

“Dunham’s book is one of those rare examples when something hyped deserves its buzz. Those of us familiar with her wit and weirdness on HBO’s Girls will experience it in spades in these essays. . . . There are hilarious moments here—I cracked up on a crowded subway reading an essay about her childhood—and disturbing ones, too. But it’s always heartfelt and very real.”—New York Post

“We are comforted, we are charmed, we leave more empowered than we came.”—NPR

“Touching, at times profound, and deeply funny . . . Dunham is expert at combining despair and humor.”—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Most of us live our lives desperately trying to conceal the anguishing gap between our polished, aspirational, representational selves and our real, human, deeply flawed selves. Dunham lives hers in that gap, welcomes the rest of the world into it with boundless openheartedness, and writes about it with the kind of profound self-awareness and self-compassion that invite us to inhabit our own gaps and maybe even embrace them a little bit more, anguish over them a little bit less.”—Maria Popova, Brain Pickings

“Reading this book is a pleasure. . . . [These essays] exude brilliance and insight well beyond Dunham’s twenty-eight years.”—The Philadelphia Inquirer

From the Hardcover edition.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurFourth Estate Ltd

- Date d'édition2014

- ISBN 10 0008101264

- ISBN 13 9780008101268

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages288

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 24,65

Frais de port :

EUR 3,29

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Not That Kind of Girl: A Young Woman Tells You What She's Learned

Edité par

Random House

(2014)

ISBN 10 : 0008101264

ISBN 13 : 9780008101268

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0008101264

Acheter neuf

EUR 24,65

Autre devise

Not That Kind of Girl: A Young Woman Tells You What She's Learned

Edité par

Random House

(2014)

ISBN 10 : 0008101264

ISBN 13 : 9780008101268

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0008101264

Acheter neuf

EUR 27,29

Autre devise