Articles liés à The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We...

Synopsis

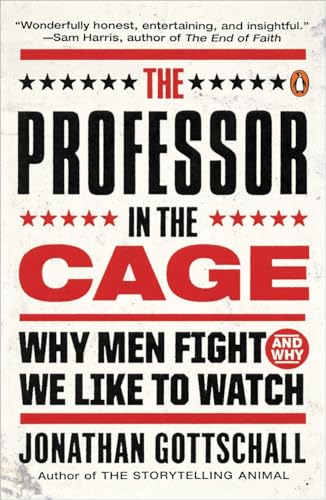

An English professor starts training in mixed martial arts, exploring the science and history behind the violence of men

When a mixed martial arts (MMA) gym opens across the street from his office, Jonathan Gottschall sees a challenge. Pushing forty, out of shape, and disenchanted with his job as an adjunct English professor, he works up his nerve and finds himself training for an all-out cage fight. He sees it not just as a personal test, but also as an opportunity to answer questions that have intrigued him for years: Why do men fight? And why do so many seemingly decent people love to watch?

In The Professor in the Cage, Gottschall’s unlikely journey from the college classroom to the fighting cage drives an important new investigation into the science and history of violence. The surging popularity of MMA—a full-contact sport in which fighters punch, choke, and kick each other into submission—is just one example of our species’ insatiable interest both in violence and in the rituals that keep violence in check. From duels to football to the roughhousing of children, humans are masters of what Gottschall calls the monkey dance: a dizzying variety of rule-bound contests that establish hierarchies while minimizing risk and social disorder. Gottschall’s unsparing odyssey—through extremes of pain, occasional humiliation, his wife’s incredulity, and ultimately his own cage fight—opens his, and our, eyes to the uncomfortable truth that, as brutal as these contests can be, the world would be a much more chaotic and dangerous place without them.

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

À propos de l?auteur

Jonathan Gottschall is a distinguished research fellow in the English Department at Washington & Jefferson College. His research has been covered in the New York Times Magazine, the New York Times, Scientific American, the New Yorker, the Atlantic, the Chronicle of Higher Education, and on NPR. His blog, The Storytelling Animal, is featured at Psychology Today. His book, The Storytelling Animal, was a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice selection and a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

Extrait. © Reproduit sur autorisation. Tous droits réservés.

PREFACE

It’s the night of March 31, 2012, and I am standing half naked in a chain-link cage. I’m bouncing restlessly from foot to bare foot, trying to vent the tension building at my core. I’m surrounded by a swarm of men in Tapout T-shirts who are hooting at me over cups of beer. I can see the young man coming through the crowd to break my face, to strangle me to sleep. It’s like a nightmare.

I’m thirty-nine years old. I’m an English teacher at a small liberal arts college. My first book, The Rape of Troy, focused on the science of violence—from murder to genocidal war—but I learned all I know from an armchair. I’ve never experienced real violence, never even been in a fight. But that’s about to change.

As I dance and pace, I watch them smear the young man’s face with Vaseline, watch them slip a mouthpiece between his lips. He’s making fists in his fingerless gloves, and I can hear my own gloves creaking as I do the same. People have the wrong idea about the gloves. They think they civilize the sport, but they are the soul of its barbarism. The fine bones of the hand are no match for a heavy skull. Knuckles shatter on heads. But if you wind the hand in ribbons of gauze and tape, then armor it in foam and leather, you turn the fragile fist into a fearsome club.

The young man strides up the steps to the cage, sinews writhing beneath his skin like snakes. The steel door clangs shut behind him, and they drive the bolts home, locking us in to battle until one of us can’t. The referee moves to the center of the cage. We will be fighting very soon, and I’m so relieved that I don’t feel the fear that I expected. There’s fear, but not the kind of terror that might unman me, might tempt me to hop the fence and run for home. Mainly I feel a sharpness of focus that I’ve never felt before. There’s nothing in the world except the young man—no sound or scent, no wife squirming in her seat, no cornerman murmuring soothingly at my back.

The referee stands sideways between us. He shouts to each of us in turn, “Fighter, are you ready?” We nod. In the next heartbeat civilization will melt away, the law will disappear, and we will meet at the center of the cage to try to kill each other. I have never seen the young man before, and I feel nothing for him but respect. And yet the crowd will cheer as I try to shut down his brain with punches, to wrench his joints, to throttle his neck until his eyes roll blindly in their sockets.

The referee yells, “Fight!” And so we do.

• • •

IT WAS THE CULMINATION of a journey that began two years earlier when I was sitting in the cubicle I shared with other English Department part-timers, mulling the disappointments of my academic career. I had a PhD, my name was on the cover of a few books, and I had already lived my fifteen minutes of fame (or what passes for it among university types), but I was still a lowly adjunct making $16,000 per year teaching composition to freshmen who couldn’t care less. My career was dead in the water. I’d known it for a long time. Whether this was because my effort to inject science into the humanities was before its time (the narrative that gets me through the day) or because that effort was wrongheaded (the more popular narrative in English departments) wasn’t the question. The question was whether I could summon the courage to move on to something new, or at least to provoke my bosses into firing me.

As I paced between my cubicle and the adjoining lounge, a streak of motion caught my eye, and I went to the window. There used to be an auto parts shop directly across the street from the English department. But now a new product was on display in the building’s big showcase windows. There were two young men in a chain-link cage. They were dancing, kicking, punching, tackling, falling, and rising to dance some more. There was a new sign on the building: MARK SHRADER’S ACADEMY OF MIXED MARTIAL ARTS. I stood at the window for a long time, peeping at the fighters through the curtains, envying their youthful strength and bravery—the way they were so alive in their octagon while I was rotting in my cube.

I began to fantasize. I saw myself walking across the street to join them. The thought of my peace-loving colleagues glancing up from their poetry volumes to see me warring in the cage filled me with perverse delight. It would be such a scandal. That’s how I’ll do it, I thought with a smile. That’s how I’ll get myself fired.

Over the next months, I began to plan a book about a cultured English professor—a lifelong specialist in the art of flight, not fight—learning the combat sport of mixed martial arts (MMA). The book would be part history of violence, part nonfiction Fight Club, and part tour of the sciences of sports and bloodlust. It would be about the struggles—sad and silly and anachronistic though they may seem—that men endure to be men.

One day, not long after noticing the cage fighting studio across the street from my office, I met my family for lunch. When I ordered a salad, my wife gave me a skeptical look. “Salad?” she asked. “Are you okay?”

“Yeah,” I said. “But I’m so fat. Gotta get in shape.”

When she asked why, I told her—a little shamefacedly—my whole dumb plan for becoming a cage fighter. “Why would you do that?” she asked. I fumbled for an honest answer. “You’ll be killed,” she pointed out. “You have no skills.”

Learning that my wife had no respect for my skills hurt, but it hurt worse to see how casually she learned to treat my danger. Much later, when I was having trouble getting a fight here in Pennsylvania (the state commission does not make it easy for older fighters), she recommended that I fight in Las Vegas, where her brother lives. “Anthony knows a lot of fighters,” she said. “I bet he could help get you a fight.”

The very idea made me clammy. “Vegas is the fight Mecca of the whole universe,” I explained to her. “I’m not exaggerating. Those guys would end my life. They would send me home to you in buckets.” A big part of me wanted her to talk me out of my whole suicidal plan. I wanted her to seize my hands and tell me through her big, pretty, man-slaying tears that it was just too dangerous and that she couldn’t stand the thought of scars on my handsome face. But instead she stared off into space like a prisoner dreaming of freedom.

“Yeah,” she said, “you should definitely fight in Vegas.”

But my wife’s question was a good one. Why did I really want to do this? Was I having a midlife crisis? I didn’t think so. Did taking up MMA—a sport where the whole point is to violently incapacitate the other guy before he can violently incapacitate you—seem like fun? It didn’t. Did I actually think that the cage could free me from the cubicle? Yes, I was just desperate enough to hope that it could. But there was more to it than that. I wanted to fight because I was simply fascinated by fighting, and I wanted to learn about it—and write about it—from the inside. I wanted to fight because I’d always admired physical courage, and yet I’d never done a brave thing. I wanted to fight, I suppose, for one of the main reasons men have always fought: to discover if I was a coward.

So in January 2011 I finally made the short walk from the brick and leaf of my college to the grit and stink of the local fighting academy. Beneath the English Department’s windows, I began studying the fighting arts alongside students, soldiers, frackers, an actuary, a busboy, a rock singer, a tree trimmer, and the occasional young woman. And each night I carried home, along with my bruises and abrasions, powerful insights into why violence is so attractive—and so repulsive.

When I crossed the street to try to become a fighter, I never stopped being a professor. I never stopped noticing the basic questions that hang in the humid air of an MMA gym, and I never stopped trying to answer them. There were the biggies: Why do men fight? Why do so many people like to watch? And why, especially when it comes to violence, do men differ so greatly from women? And there were the questions that seemed small at first but ended up having large implications: Why do human beings spend (waste?) so much energy on sports? Are traditional martial arts such as karate and kung fu sheer hokum? Why do fighters try to stare each other down? And why do nonhuman primates do exactly the same thing?

When I first joined the gym, I expected to write a book about the rapid rise of cage fighting in America and what its massive popularity says about us—not just as a nation, but as a species. I thought MMA was bad for the athletes who did it and bad for society at large. I saw cage fighting as a metaphor for something darkly rotten at the human core. But my library research convinced me that MMA tells us nothing particularly interesting about our place or time; everywhere and always, people have loved to watch men fight. And my gym research—sparring, interviewing, and finally fighting myself—upended all my other preconceptions. In short, I set out to write about the darkness in men, but I ended up with a book about how men keep the darkness in check.

One big idea threads through all the chapters to come: While always anchored in MMA, The Professor in the Cage is about the duels of men, broadly defined. Most historians trace the origins of the duel back to Europe in the 1500s. But far from being a Western invention, the duel is not even a human invention. Animals have their fights, too, and biologists refer to them tellingly as duels, sports, tournaments, or, most commonly, ritual combat. Ritual combat—think of elephant seals clashing in the surf, or deer locking antlers—establishes dibs on all good things through restrained contests that diminish risk. The same is true of human contests, only more so. Humans, especially men, are masters of what I call the monkey dance—a dizzying variety of ritualized, rule-bound competitions. These events range from elaborate and deadly duels (pistols at dawn), to combat sports such as MMA or football, to the play fights of boys, to duels of pure language (rap battles, everyday pissing contests). They often seem ridiculous and sometimes end in tragedy. But they serve a vital function: they help men work out conflicts and thrash out hierarchies while minimizing carnage and social chaos. Without the restraining codes of the monkey dance, the world would be a much bleaker and more violent place.

ONE

THE RIDDLE OF THE DUEL

The trouble with this country is that a man can live his entire life without knowing whether or not he is a coward.

John Berryman

The first cage fight in the history of the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) occurred on November 12, 1993, pitting karate against sumo. There were no rules. There were no rounds. There were no weight classes. There were no gloves. There was no mercy. There was also no ring.

The UFC’s creators wanted the fighting space to drive home the whole point of the sport—which was that it wasn’t a sport. It was, in the words of its first announcer, Rich “G-Man” Goins, “combat in its most basic equation: Survival or destruction.” The creators considered locking the fighters in an electrified cage surrounded by a moat full of famished alligators, but they decided that was a bit much. Instead, the men would fight in a chain-link octagonal cage, which one announcer likened to the “pits” used in dogfighting. Once the fighters entered the cage, officials would bolt the door behind them, and the only way out would be through the other man. To quote the G-Man again: “The rules are simple—two men enter, one man leaves.” (It’s probably no coincidence that in Mel Gibson’s 1985 dystopian fantasy Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, the crowd chants “Two men enter; one man leaves” as gladiators fight inside a steel cage.)

The first fighter to step into the UFC cage was a mountainous Hawaiian sumo wrestler named Teila Tuli. He walked through the crowd wearing traditional island garb resembling a checkered muumuu, paired with a ski hat. He handed his hat and gown to his cornermen, then danced around the cage in his Hawaiian skirt, looking loose and confident. Teila Tuli was six feet two, sleekly bald, and massively obese. At more than four hundred pounds, he was fat in all the ordinary places—thick in the hams, belly, and jowls. But at some point he maxed out the fat-storage capacity of the ordinary places, and so his body started laying in cellulite bags wherever it could. Tuli had several bags pinned between his chest and upper arms, as well as a blubbery roll fitted like a pillow to the back of his neck. Even so, he was a magnificent animal, with huge muscles twitching beneath the fat. Despite the bulk, he moved as nimbly as a dancer and dropped effortlessly into deep stretches. Teila Tuli was a formidable athlete.

Tuli’s opponent was a Dutch karate black belt named Gerard Gordeau, and compared with the Hawaiian he wasn’t much to look at. Gordeau was tall and skinny, with a buzz cut and scraggly chest hair. With his thin arms and almost defiantly unripped torso, he didn’t look like an athlete at all. Instead, he looked exactly like what he was: a guy who made his living as a school janitor, while competing in karate tournaments on the side. Gordeau walked to the cage wearing karate pants and a white towel draped over his shoulders. Though he was only moments away from fighting an athlete who was double his size, he looked about as troubled as a guy walking from the shower to his bedroom.

When Gordeau entered the cage, Tuli’s mask of serene confidence—of manly insouciance—began to slip. Tuli moved nervously in his corner, sucking down huge lungfuls of air and spewing them out again. As the camera panned to Gordeau’s corner, it was clear why. Gordeau didn’t look like a man who was about to be sacrificed to a giant. He just stood there, flat-footed, slump-shouldered, and breathing normally through his nose, as if he were running a pulse of about forty. And he watched Tuli not with the “mean mug” of a fighter trying to intimidate, but with a serial killer’s blank stare. His look said to Tuli, not unkindly, This is nothing to me. You are nothing to me.

The bell rang, and after a few seconds of circling and feinting Tuli tipped himself toward Gordeau and let gravity take over. Gordeau pivoted like a matador and stung Tuli with a hard punch as he charged by. Unbalanced, Tuli crashed face-first into the bottom of the fence. As the huge man struggled to rise, Gordeau stepped in, wound up, and soccer-kicked Tuli, full power, in the mouth. The crack of the blow was so terrible, the spray of blood and slobber so dramatic, that the referee jumped in to stop the fight. But not before Gordeau crouched down for a haymaker that spun Tuli around and left him sagging against the fence. The fight lasted twenty seconds. Tuli hauled himself upright and shuffled out of the cage, complaining through the gory hole of his mouth that he wanted to fight on. Gordeau left the cage with a fractured right fist and one of Tuli’s front teeth broken off inside his foot. Gordeau had punted Tuli’s other front tooth straight through the chain-link cage, past the announcers’ heads, and into the crowd.

• • •

I DIDN’T SEE Gordeau fight Tuli live. I saw the fight a few years later at a party when a friend cracked open a Blockbuster video case and jammed a tape into a VCR. He said, “Check this out. You guys won’t believe it.” I didn’t believe it. Watching Gordeau punt Tuli’s face, then watching replays of him punting it again and again, from multiple super-slo-mo angles, made me sick to my stomach. And listening as my friends yelped and giggled through the onslaught—watching as men in the Denver crowd screamed through conniptions of bloodlust—sickened me even more. I asked myself, What kind of savage would want to watch this? And then the next pair of fighters strode into the cage, and I found that I couldn’t look away.

That night we gorged ourselves on raw violence. When it ended, with a skinny Brazilian choking Gordeau into submission in the final fight, I staggered home feeling exactly like I’d felt after seeing my first porno as a teenager. The porn tape, like the UFC tape, was a fleshy catastrophe that raised serious ethical issues. After both experiences I lay awake trying to erase the images of swollen flesh and spattering fluids strobing in my mind. And in both cases I awoke still feeling disgusted and disturbed—but also wanting to see more. And soon. In the ensuing months I frequently visited the video store, where I guiltily lurked through the section that included UFC tapes, professional wrestling tapes, and tapes from an infamous video series called Faces of Death.

I told myself that unlike the blood-drunk men raving in the UFC crowd, I had a good reason for watching. In my early twenties I was a devoted, if basically inept, karate student, and the UFC was an education about what worked in a real fight and what absolutely didn’t. I watched the tapes in a scholarly spirit, rewinding over and over to study particularly cool moves—etching them in my mind so I could drill them with my karate friends. But I didn’t try too hard to fool myself. I watched the tapes to learn, but also because I was a lot like those UFC fans cheering for carnage—I just had the good taste not to show it. I watched because the fights excited me. I watched because fighting was real, high-stakes drama with no acting and no artifice. I watched because I envied the manly excellence and courage of the fighters. I watched because—God help the human race—there’s nothing harder not to watch than two men fighting.

And I watched because I was deeply confused. As I took in the footage of Gordeau shattering Tuli’s teeth, the questions of this book were already forming in my mind. Why do men fight? And why are seemingly decent people drawn to watch? I didn’t know it at the time, but that night I began a research project that would last almost twenty years and culminate in this book.

EN GARDE!

To begin, I have to take you back more than two hundred years to tell the story of a different fight—a story you only think you know.

Before dawn on November 23, 1801, Hamilton, his second, and his surgeon eased aboard a wobbly dinghy, and a ferryman rowed them away from Manhattan (and its laws against dueling) to the Jersey side of the Hudson River. Hamilton crunched through the forest into a clearing, where his adversary was already busy with his own second, clearing away branches and pacing off the agreed distance—ten paces, or around thirty feet. Hamilton stood off to one side, eyeing his opponent through the slanting dawn light, feeling no hatred toward him. He was thinking, How strange and stupid this is. He was thinking, Don’t let your hands shake. He could hear the seconds droning through their last, pro forma attempts at reconciliation. Although both Hamilton and his opponent had much to be sorry for, neither could say so for fear of appearing cowardly.

The two men would fight with a pair of dueling pistols that belonged to Hamilton’s uncle. The pistols were handcrafted, gorgeously filigreed objects of art and death. With dark walnut stocks and gleaming barrels, they were about the size of sawed-off shotguns, and with their .54-caliber balls they could open a man about as wide. The seconds loaded the weapons, each using a ramrod to pack in powder, ball, and wadding, then handed them to the duelists by the barrels. Hamilton took his place and tried to avoid his adversary’s gaze. It was his first duel, and he could not believe how close together they were standing. They could almost duel by spitting.

We don’t know for sure, but the men may have arranged themselves in classic dueling stances that were designed to shrink the profile and shield the vital organs. If so, they would have positioned themselves sideways to each other, sucking in their bellies and tucking their chins to hide their necks. They would have turned their hips in hopes of taking a low shot in the buttock and not the groin. Thus contorted, they would have stood with their pistols dangling, awaiting the command to fire. When the command came, they would not have fired with their arms extended to full length. Instead, they would have fired with their right elbows cramped tight to their ribs so their pistols and arms could shield their torsos.

“Present!” said one of the seconds, commanding the duelists to raise their weapons and fire. But neither man did. They just stared at each other across the stillness of the clearing, their breath clouding the morning air. They stared at each other for a long time, perhaps hoping that someone might still call this madness off and they could embrace and part as friends. After a full minute had passed, Hamilton raised his weapon. The clearing erupted with two near-simultaneous explosions. The two lead balls passed each other in flight, one sizzling wide into the trees, and the other steering around Hamilton’s gun arm to bite into the soft flesh beneath his ribs. The ball punched a fist-size hole through his innards before exiting through his left side and lodging in his opposite arm. Hamilton fell face-first to the earth. Once back in Manhattan, he lay in bed for more than twenty-four hours, writhing in agony and trying to die bravely.

And now we come to the part of the story you probably don’t know. When Hamilton’s father received news of the catastrophe, he raced to his son’s bedside. The father—Alexander Hamilton, the man whose handsome face still graces the ten-dollar bill—climbed carefully into bed with his doomed son Philip and gave vent to his grief. One of Philip’s friends was looking on and said that Alexander’s sorrow “beggared all description.” The nineteen-year-old Philip was Alexander’s eldest and favorite child, the one he’d doted on as a baby and later called “the brightest, as well as the ablest, hope of my family.” When Philip was buried, Alexander had trouble walking to the graveside; as one observer wrote, he had to be half carried to “the grave of his hopes.”

And yet, less than three years later, still mourning Philip and knowing he was in the wrong, Alexander had himself rowed away from Manhattan to the Jersey banks of the Hudson, directly across the river from Forty-second Street. There, at Weehawken, on a lovely summer morning, he was greeted by the vice president of the United States, Aaron Burr. When the two men fired, Hamilton fell, perhaps cut down by the very same pistol that had killed Philip. (Hamilton and Burr certainly used the same set of pistols.) Gut shot like his son, Hamilton’s death throes lasted thirty-eight hours. His agony was, according to his surgeon, “almost intolerable” and not much deadened by opium.

Philip Hamilton was killed by one of his father’s many political adversaries, a twenty-seven-year-old lawyer named George Eacker. One night at the theater, young Philip, possibly drunk, stormed Eacker’s private box with a friend and abused the lawyer for criticizing his father in a speech. Afterward Philip wouldn’t apologize for his insults. He was too enraged over the way Eacker had insulted him in reply, calling him a “damned rascal.” These were, quite literally, fighting words. A man called someone a rascal—or a puppy, a jackanapes, a coxcomb, or a liar—only if he specifically wished to provoke a duel.

Aaron Burr called out Alexander Hamilton for more serious affronts. Hamilton was outwardly friendly to Burr when they met on the street or socialized in each other’s Wall Street homes. In later years Burr would sometimes speak of “my friend Hamilton—whom I shot.” But Hamilton deeply distrusted Burr’s politics and character and said that he felt “a religious duty to oppose his career.” Rather than confront Burr openly, however, Hamilton opted, in the parlance of the day, to slit Burr’s throat with whispers. Hamilton may have had a hand in newspaper accounts that accused Burr of, among other depravities, treason, being named as the best customer of no fewer than twenty whores, and twirling buxom girls at a “nigger ball.” Burr believed that Hamilton was smearing him, and his suspicions were confirmed when Hamilton was quoted in a newspaper calling Burr a “profligate” and a “voluptuary in the extreme,” with implications that he had said far worse.

On the eve of his duel, Hamilton tried to put his affairs in order. He updated his will and wrote a letter to his wife, Elizabeth, whom he addressed as “best of wives, best of women.” The letter explained that he was fighting Burr with the greatest reluctance and only after exhausting all other options. This was true. Burr and Hamilton had traded endless letters back and forth through their seconds, with Hamilton working lawyerly dodges and splitting verbal hairs, trying to weasel out of the mess on a technicality. He was reluctant to fight because he didn’t hate Burr and he felt that dueling was radically at odds with good Christian behavior. Moreover, Hamilton knew that if he died, his family would struggle to pay their debts.

So why, when they had so much to live for, did the Hamiltons, father and son, recklessly risk their lives over such paltry stuff? Alexander Hamilton was a co-author of The Federalist Papers and the architect of the American financial system. Couldn’t he do the cost-benefit math?

To us moderns the killing of a former Treasury secretary by a sitting vice president seems fantastically exotic. (Remember the uproar in 2006 when Vice President Dick Cheney accidentally wounded a friend in a quail-hunting accident? Well, imagine the hullabaloo if Cheney had killed Clinton’s former Treasury secretary Robert Rubin in a shoot-out on the Virginia side of the Potomac, and had then gone on the lam.) But a little more than two centuries ago, there was nothing particularly strange about the Burr-Hamilton affair—not the high social and political status of the combatants, nor the way that the effect (a deadly gunfight) seemed so out of proportion to the cause (gossip). Throughout the five-hundred-year history of Euro-American dueling culture, aristocratic men were generally prepared to kill each other at the drop of a hat. In sharp contrast to modern times, in those days it was educated, rich, and powerful men—blue bloods, newspaper owners, congressmen, future presidents, British prime ministers—who were most likely to shoot or stab each other over disses.

It’s easy to see why men fight over precious and necessary things such as food, wealth, or the love of a woman. But duelists so often killed, and were killed, over trifles—loose words, rumors, impertinent looks. Duelists imperiled their lives for something they couldn’t touch, see, or even precisely define: their personal honor. This is the riddle of the duel: how could intelligent men risk so much over what seems like so little?

HONOR

Killing a man in cold blood because he has called you a voluptuary or ruined your night at the theater seems deranged. But that’s because most of us today don’t fully grasp the historical importance of honor. In the Hamiltons’ time, honor represented the entirety of a man’s social wealth. Honor wasn’t some trivial thing; it was precious coin that bought the best things in life. And if this coin was devalued, a man’s prospects—and the prospects of his entire family—were devalued as well.

Muscular cultures of honor still exist today, and where they do, it’s easy to see honor’s value. Take prison. If a mad scientist wanted to run an experiment that plunged deep down to the roots of masculine aggression, he could do no better than to take many hundreds of frustrated young men, isolate them from the softening influence of women and children, see that they are armed with all kinds of ingeniously improvised weapons, and cage them together for years on end in circumstances that give them little hope of ever prospering outside the walls. Prisons are the most extreme honor cultures currently in existence. The harder the prison, the harder the culture of honor. And what emerges from such cultures is a lot of violence. In prison, inmates fight over tangible things such as control of a black-market economy in drugs, booze, and other contraband. But as frequently they fight over honor, although they usually don’t call it that. They call it respect. But honor and respect are different words for the same thing. They represent a group’s estimation of a man’s ability to inflict harm and confer benefits—of his power, in other words.

It may seem odd to think of a prison as an honor culture, because for us honor has noble connotations. But a culture of honor can tolerate extremely ignoble behavior—from Alexander Hamilton’s profane gossip to the rapes and murders in modern American jails. A culture of honor is really nothing more than a culture of reciprocation. A man of honor builds a reputation for payback. In a tit-for-tat fashion he returns favors and retaliates against slights. Consider the case of Jimmy Lerner, a corporate number cruncher who got locked up for killing a friend in a fight and afterward wrote a prison memoir called You Got Nothing Coming. Early in his sentence a massive inmate called Big Hungry approached Lerner in the crowded lunchroom, lifted a banana from Lerner’s tray, and sauntered away as he peeled it. On a second occasion Big Hungry wordlessly cut in front of Lerner in the phone line. On both occasions Lerner was more chagrined than annoyed, and he let the slights pass with a shrug.

Lerner was lucky in having a formidable cell mate named Kansas, who was still a young man but old in the ways of prison. After the phone incident Kansas told Lerner that he had no choice but to kill Big Hungry. “Kansas, that seems a little extreme, don’t you think? Stabbing a guy over a phone call?” Kansas replied, “It ain’t about the phone call, O.G. It’s about Respect.” Lerner explains: “Ask any convict who has been down a few days for his definition of a ‘man’ and the concept of ‘disrespect’ will surface quicker than stank on shit . . . ‘A man,’ Kansas might say, ‘is someone who tolerates no disrespect! A real man, a stand-up man, seeks out disrespect and destroys it!’”

A different convict, a thirty-five-year-old armed robber named Peter, explains why. “You can tell the rabbits . . . They bring this guy in and he is doing time for some punk-ass white-collar rip-off, and right away I figure this guy’s got no heart.” So Peter gives the new guy a “heart check” by harassing him on little things—stealing his books in the same way Big Hungry stole Lerner’s banana. By failing to retaliate, the new guy fails the heart test, just as Lerner did. Peter says, “I mean, c’mon, a righteous motherfucker would have stuck me, ’cause he’s gonna know that if he lets me take his law books, I’m coming back for his ass next. I’m no fool. A few days later, I go up to this dude and tell ’im we are forming a partnership. He’s gonna do my laundry for me and buy me whatever I want from the commissary and that’s just how it’s gonna be . . . You see, that’s how it is with rabbits. You ever wonder what they are good for, or why God made them? They’re food.”

In a tough prison, you can either be a “righteous motherfucker”—a missile programmed to seek out and destroy disrespect—or you can give up your ass, often literally but figuratively, too. If you fail the heart test, the other inmates will take your food, exploit your commissary privileges, extort your relatives, and make you a slave. The prison equation is ruthlessly simple: yielding on the smallest thing (a banana, a book) is equivalent to yielding on the biggest. Not fighting over a banana or a book is the same as declaring I am a rabbit. I am food.

In prison men defend honor because honor is necessary to life. The most respected prisoners have the best lives, while the least respected have no lives at all. Prison culture provides an exaggerated—and thus clarifying—insight into why men like the Hamiltons were willing to risk so much over honor. In the upper strata of European and American society, not dueling in defense of honor was a form of suicide. Men risked death or injury (throughout history, most duelists managed to walk or limp away afterward) to avoid the certainty of social annihilation. Some historians have speculated, lamely, that Hamilton fought Burr because he was suicidally depressed over Philip’s death, a daughter’s mental illness, political setbacks, and constant money problems. But this is wrong. Hamilton desperately sought a face-saving way out of the duel and fought Burr not because he wanted to kill or die, but because he so much wanted to live.

To dodge the fight Hamilton would have had to apologize to Burr and effectively admit to a history of low and dirty lies. If Hamilton simply refused to fight, Burr would have instantly “posted him,” literally printing the news that Hamilton was a coward. To be seen as a duel dodger was, in many ways, a fate worse than death. Backing down would have jeopardized Hamilton’s political ambitions, his position of social eminence, and his business as a lawyer. Hamilton’s family would have been tainted as well—his wife unable to show her face in society, his children’s prospects diminished professionally and romantically. Hamilton fought not because he was brave, but because he was scared of what it would cost him not to fight. As one of Hamilton’s friends wrote after his death, “If we were truly brave, we should not accept a challenge; but we are all cowards.”

BRAIN DAMAGE

Two centuries after the Hamiltons tromped through the New Jersey woods to their deaths, I was crossing an octagonal cage to face mine. I tapped fists with my coach, Mark Shrader. We circled away from each other, then reengaged.

Mark Shrader (right) posing with champion boxer Roy Jones Jr. Shrader served as a sparring partner for Jones as the latter prepared for his 2008 fight against Felix Trinidad. Note the enormous size of Shrader’s left fist and then read on.

I was a few months into my MMA adventure, and I was already getting impatient. I knew that for a book with a “memoir stunt” component to work, I’d need to get hurt and humiliated, early and often. From George Plimpton’s forays into professional sports to the gentler stunts of A. J. Jacobs (such as spending a year living as an extreme biblical fundamentalist), the formula is pretty much set: ordinary schmuck enters an exotic world; suffers humorous setbacks, agony, and shame; learns a lot along the way. But so far I’d hardly been hurt or humiliated at all. The guys at the gym seemed to be treating me gently, either because I was new or because they feared for my ancient, chalky bones. So one day I blurted to Coach Shrader that I wanted to boost my training. I was writing a book about fighting, and I had to know what it was like to be hit.

I actually said that. It was a foolish thing to say and, as I would learn, an even more foolish thing to say to Mark Shrader. Mark is black-haired and handsome, with just a touch of what the boxing writer F. X. Toole calls “the monkey look”—the pugilist’s scar-thickened eyebrows and fist-flattened nose. He has a quick, charismatic smile and the infectious energy of a boyhood martial arts fanatic who grew up to do exactly what he wanted with his life. But Shrader’s also had more than thirty fights as an amateur boxer, kickboxer, and MMA fighter. And as he was edging into his late thirties, he was going through a hard transition—from being an ambitious fighter who simply must dominate everything that moves in a gym to being a teacher whose job is building up, not beating down.

The round began, and I moved forward with my gloves high. We played a bit of patty-cake, pecking each other with jabs and catching them in the palms of our mitts. He started to throw another jab, and I reached out to block it with my right glove. Mark had repeatedly warned me not to reach out to intercept punches, and now he showed me why. The jab was just a feint, and he lunged forward, hooking his fist around my outstretched glove and caving it into the right side of my face. Mark likes to quote Sun Tzu: “All warfare is based on deception.”

Earlier that week, I’d held the focus mitts during class while Mark hammered them with punches, demonstrating a two-three combination: right cross followed by atomic left hook. Mark was showing us the brutal, simple physics of hitting. He was twisting his whole body in one direction, then untwisting it the other way; coiling up his life force and uncoiling it as a death force—coiling and uncoiling. Mark says that a fighter’s fist is “just the messenger” because its job is to deliver energy generated by the whole body. And the energy it can deliver is enormous, greeting the skull like a twelve-pound mallet moving at twenty miles per hour and imparting as many as one hundred Gs of force. Feeling Mark rip those Gs through the focus mitts and into my arms made me marvel at the toughness and resilience of the human skull, brain, and neck—that men can be clubbed with such heavy punches and keep living. Now I’d taken one of those punches, and I was still alive.

Rocky Marciano’s right cross greets Jersey Joe Walcott’s chin. You can’t see it, but the same shock wave deforming Walcott’s face is also rolling and twisting through the soft stuff of his brain.

But just barely. With the punch pain detonated inside my brain. Gloved punches don’t hurt your face all that much, unless they flatten your nose or crush a tooth through your lip. The padding distributes the force and dulls the pain. But the full shock wave of the punch still passes through the skull to slosh and jiggle the brain in its casing, just like Jell-O in a mold. Neuroscientists don’t fully understand the physiology of a knockout, but here’s the gist. The brain is a soggy, fatty, gelatinous meat computer, with chemicals and electrical signals running through its trillions of wispy connections. The shock wave from a heavy blow rolls through the brain like a tsunami, shearing connections and disrupting signals. Effectively the brain shorts out. And the man falls stiff and twitchy to the mat until the brain can reroute the signals and get back online. Feeling that instantaneous brain pain was a eureka moment for me. It made me really get—in a way that just watching fights can’t—that the main object of fighting sports is to temporarily shut down the other guy’s brain. Head punches hurt what they are designed to hurt: not the face, the brain.

Simultaneous with the brain pain my consciousness flickered out, and I started to tip like a chopped tree. But in the next moment I realized that it was just my perception of the world that was tipping, not my actual body, and when I blinked, the world heaved itself upright. I realized that I was reeling across the cage and Shrader was pursuing with a predatory look in his eyes. I backpedaled, weaving here and there, bouncing off the cage. A few times I literally turned my back on Mark in panic and ran for it. But no matter how fast I fled, he was always right there hitting me. The barrage never stopped. Shots to the belly, shocks to the arms, whip-crack jabs, bomb crosses, and the terrible concussive explosions of his left hooks going off inside my brain—filling the cage with a snow of glinting, golden flakes. I tried to fight back, flailing my arms in Mark’s general vicinity, but he seemed almost offended that I had the gall to try to hit him, and he stung me with counterpunches.

After what seemed like forever, Mark backed off to let me gasp. Hiding behind my gloves, I flicked my eyes at the clock. The sight crushed me. There were still nearly two minutes left in a three-minute round, and I was already worn-out from the punches, the running, and the fear. Realizing that I was almost helpless from fatigue after just sixty seconds was a second eureka moment. Unless you’ve fought in the cage, it’s hard to grasp how exhausting it is. MMA fans know that fighters have to be strong and skilled, but few really appreciate how freakishly fit the best guys are. MMA demands a sprinter’s explosiveness and a marathoner’s stamina. When the pace is hot, when the match mixes the constant footwork of striking with the heavy exertion of grappling, the experience feels like sprinting uphill, like drowning in a sea of air. Fighters call it gassing out. And when you gas out, that’s it; you’re done. Your brain sends commands, but your body can’t respond, or it responds so sluggishly that it’s useless.

In MMA, as in other sports, it is conventional to speak of “heart.” A man with a lot of determination and fighting spirit, a man who never quits, is said to have a lot of heart. This is meant as a metaphor, but it’s also literally true. The quality of the physical heart—its ability to push oxygenated blood through the veins—is the best indicator of fighting spirit. A guy in great shape is literally great-hearted. Fighters break when their hearts break—when the heart muscle can’t keep up with the body’s demand for oxygen.

My heart was sorely taxed, but it wasn’t broken, and so when Mark came forward again, I tucked my chin and raised my fists against him, just as he’d taught me. When the round finally ended, Mark gave me a little half hug and apologized: “Sorry, man, that first hook got away from me.”

“That’s okay,” I said, meaning it. He’d given me only what I was stupid enough to ask for. And besides, he’d also just given me the most intensely educational three minutes of my life.

Mark tousled my hair with a gloved hand and said, “Now you know what it’s like!” I watched him cross back to his side of the cage. I was thinking, I’m alive right now only because he likes me better this way.

Afterward I felt concussed. For the rest of that day and into the next, my vision and thinking were hazy, like someone had thrown a translucent blanket over my head that dulled my perception and slowed my mind. My head throbbed in rhythm with my heart, and when I cleared my sore nose, clots of black blood appeared in the tissue. The whole left side of my face felt as if it had been pushed in by that first left hook, from my right eyeball down to my swollen lip. One of the punches seemed to have knocked most of the feeling out of my mouth, except that touching my aching right eye was like pushing a button that delivered an electric jolt of pain to my front teeth.

Midway through sparring with Mark and feeling him attack my brain again and again, it occurred to me that this was very reckless and stupid. I make my living trying to think smart thoughts. I’d better cry uncle while I still know my alphabet. But I didn’t cry uncle. Why? It had something to do with honor—something to do with the other guys in the gym, lazing around the cage, watching. So when the bell rang signaling the end of our round, I had one minute to bend over, grip my knees with my hands, and suck wind. And then the bell sounded again. I had two more rounds to go.

FEAR

Fighting deadly duels over slights and gossip might seem stupid and barbaric. But we should avoid falling for a self-flattering narrative that portrays us as the enlightened ones. “Leviathan” is the name the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) gave to the huge apparatus of state power, from the laws to the judges to the enforcing cops, prison guards, and executioners. The formal duel arose in Europe when Leviathan was weak and men were largely responsible for getting their own justice. A duelist wasn’t behaving stupidly when he fought over an insult—because he wasn’t really fighting over the insult. The insult was spilled milk. He fought to keep the next guy from even thinking about spilling his milk. So there is a certain madness to the duel. Duelists risked so much for so little. But it was totally sane and smart, too. By dueling, a man demonstrated in a moment of intense risk that he would literally fight to the death anyone who crossed him. And this gave other men excellent reason not to cross him.

Neither was the duel barbaric. The duel wasn’t about authorizing unfettered violence. To the contrary, it was about fettering violence—locking it up in tight rules that were as clear and fair as the rules of tennis. The duel system evolved to civilize savage passions. It helped limit conflict to two aggrieved parties and kept it from metastasizing into what you get when you have an honor culture without a dueling system: Hatfield-McCoy–style vendettas, prison shankings, and inner-city drive-bys.

The European duel’s greatest civilizing innovation was simple delay. Offense was often given and challenges delivered in hot blood. But duel etiquette demanded a delay between the challenge and the actual duel so the seconds could try to negotiate a peaceful way out. As time passed, rage tended to give way to fear, and men would look for a way out.

On the dueling grounds, the great adversary wasn’t really the other duelist so much as the fear. To win a duel you didn’t need to shoot straight or slash gracefully. You didn’t need to kill your opponent or hurt him worse than he hurt you. You didn’t even need to survive. A duel was a bravery contest far more than a skill contest. To win all you really needed to do was show up and not show fear, even if you were mortally wounded. As one dueling manual explained, “I cannot impress upon an individual too strongly, the propriety of remaining perfectly calm and collected when hit: he must not allow himself to be alarmed or confused, but summoning up all his resolution, treat the matter coolly; and if he dies, go off with as good a grace as possible.”

Most duelists stewed through a nerve-racking waiting period ranging from a couple of days to a couple of weeks. The waiting period for my MMA duel began the moment I decided to write this book and lasted until my actual fight, more than two years later. For most of that period I lived with a sense of mild anxiety occasionally punctuated by stabs of terror. I had set out on a journey that would most likely end with a martial arts master splashing my face across the cage—hitting me in the brain as hard and as fast and as savagely as he could, until he laid me down in a dreamless sleep. But my big fear wasn’t of a concussion, or a broken nose, or a torn knee. As in Maupassant’s short story, my central fear was of fear itself. What if I panicked cageside and refused to climb the stairs? What if I unconvincingly faked a last-minute injury? What if, once the fight started, I turned and ran—sprinting in circles around the perimeter of the cage while my opponent gave chase? What if, in short, I showed myself to be a coward?

The French short story writer Guy de Maupassant (1850–1893). Maupassant’s story “A Coward” describes a man on the eve of a duel, struggling with his fear—not of death but of fear itself. The story ends with the coward sitting at his desk before dawn, inspecting his dueling pistol: “He looked at the little black, death-spitting hole at the end of the pistol; he thought of dishonor, of the whispers at the clubs, the smiles in his friends’ drawing-rooms, the contempt of women, the veiled sneers of the newspapers, the insults that would be hurled at him by cowards. He still looked at the weapon, and raising the hammer, saw the glitter of the priming below it. The pistol had been left loaded by some chance, some oversight. And the discovery rejoiced him, he knew not why. If he did not maintain, in presence of his opponent, the steadfast bearing which was so necessary to his honor, he would be ruined forever. He would be branded, stigmatized as a coward, hounded out of society! And he felt, he knew, that he could not maintain that calm, unmoved demeanor. And yet he was brave, since the thought that followed was not even rounded to a finish in his mind; but, opening his mouth wide, he suddenly plunged the barrel of the pistol as far back as his throat, and pressed the trigger.”

So, like many duelists, I spent a lot of time and energy trying to negotiate a way out of my mess. I negotiated almost exclusively with myself, constantly fondling all of the reasons I shouldn’t fight (pain, disfigurement, brain damage, paralysis, disgrace). And then I argued the other side of it. I told myself that MMA wasn’t all that dangerous. Look at how many fights I’d seen in which no one died. Plus, in Pennsylvania’s amateur divisions, striking the head of a down man—the signature MMA maneuver of “ground and pound”—is against the rules. But then I recalled how many bloody amateur scraps I’d seen—with all the full-force nose punching, gut kneeing, strangling, body slamming, and testicular hazard—which looked unpleasant enough.

Unlike most duelists, I had not only to prepare for my fight but also to steep myself to saturation in the science and history of mano a mano conflict. Fighting can be seductive. It seduces men, and it helps men seduce women, who have always been drawn to the blood on a duelist’s hands. But the more I immersed myself in the history and social science of men’s fights, the less seduced I felt. I’ve claimed that the duel was not barbaric. But of course the duel was barbaric. It was just that the duel’s restrained violence was less barbaric than the alternative, which wasn’t peace, love, and understanding, but unrestrained violence. The story of the duel is one of (usually) young men getting themselves killed over nothing, or getting their noses cut off by swords, their penises nipped off by bullets, or their brains bashed into comas over spilled beers. How sad it is that the Hamiltons, father and son, got themselves killed. How selfish of the young Russian poet Alexander Pushkin (see chapter 2) to waste his life in a duel when he still had decades’ worth of poetry locked inside him. Wasn’t there more nobility by far in not fighting than in fighting?

About nine months into my training I was pondering these questions as I hobbled around on crutches thanks to a kick to the calf that had temporarily crippled me. I was worried about the long-term damage the sparring might be doing to my brain, about all the ibuprofen I was taking for headaches. I was tired of hurting all the time—of the way my whole body had become a road for migrating pain. I was exhausted from the training and constantly famished from the dieting I was doing to lose weight. And I was a little queasy from all the fights I’d been watching, not on TV but at local MMA events.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Gratuit expédition vers Etats-Unis

Destinations, frais et délaisAcheter neuf

Afficher cet articleEUR 6,01 expédition vers Etats-Unis

Destinations, frais et délaisRésultats de recherche pour The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We...

The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch

Vendeur : Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, Etats-Unis

Etat : Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. N° de réf. du vendeur X00A-01930

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch

Vendeur : Greenworld Books, Arlington, TX, Etats-Unis

Etat : good. Fast Free Shipping â" Good condition book with a firm cover and clean, readable pages. Shows normal use, including some light wear or limited notes highlighting, yet remains a dependable copy overall. Supplemental items like CDs or access codes may not be included. N° de réf. du vendeur GWV.0143108050.G

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. N° de réf. du vendeur G0143108050I3N00

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. N° de réf. du vendeur G0143108050I3N00

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. N° de réf. du vendeur G0143108050I4N00

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch

Vendeur : Blue Vase Books, Interlochen, MI, Etats-Unis

Etat : acceptable. The item is very worn but is perfectly usable. Signs of wear can include aesthetic issues such as scratches, dents, worn and creased covers, folded page corners and minor liquid stains. All pages and the cover are intact, but the dust cover may be missing. Pages may include moderate to heavy amount of notes and highlighting, but the text is not obscured or unreadable. Page edges may have foxing age related spots and browning . May NOT include discs, access code or other supplemental materials. N° de réf. du vendeur BVV.0143108050.A

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch

Vendeur : VanderMeer Creative, Inc., Tallahassee, FL, Etats-Unis

Soft cover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 000128

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch

Vendeur : HPB-Diamond, Dallas, TX, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! N° de réf. du vendeur S_451140144

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch

Vendeur : Textbooks_Source, Columbia, MO, Etats-Unis

paperback. Etat : New. Reprint. Ships in a BOX from Central Missouri! UPS shipping for most packages, (Priority Mail for AK/HI/APO/PO Boxes). N° de réf. du vendeur 001994901N

Quantité disponible : 15 disponible(s)

Professor in the Cage : Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch

Vendeur : GreatBookPrices, Columbia, MD, Etats-Unis

Etat : As New. Unread book in perfect condition. N° de réf. du vendeur 24048623

Quantité disponible : Plus de 20 disponibles