Articles liés à The Hedgehog, the Fox and the Magister's Pox: Mending...

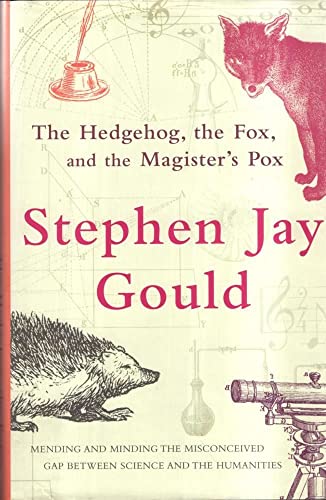

The Hedgehog, the Fox and the Magister's Pox: Mending and Minding the Misconceived Gap Between Science and the Humanities - Couverture rigide

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBN

Extrait :

The RITE and RIGHTS of a SEPARATING SPRING

Newton's Light

The epitaph czar of Westminster Abbey must have demurred, for the great man's grave does not bear these intended words. But Alexander Pope did write a memorable (and technically even heroic) couplet for the tombstone of his most illustrious contemporary. Biblical parodies, perhaps, could not pass muster in Britain's holiest of holies, both sacred and secular,* for Pope's epitome of a life well lived recalled the first overt order of the ultimate boss:

Nature and Nature's laws lay hid in night:

God said, let Newton be! and all was light.

Pope surely wins first prize for succinctness and rhyme, but we may cite any number of statements from the wisest of his contemporaries to the best of later scholars, all affirming that something truly

special roiled the world of seventeenth-century thinkers, changing the very definitions of knowledge and causality, and achieving a beginning of control over nature (or at least predictability of her ways) that previous centuries had not attained or, for themost part, even sought. Although hard to define, and even denied by some, this transforming period has been awarded the two ultimate verbal accolades by a generally timid profession of academic historians: the definite article for uniqueness, and uppercase designation for importance. Historians generally refer to this watershed of the seventeenth century as the Scientific Revolution.

To cite a key contemporary, a poet rather than a scientist, at least by current disciplinary allocations that would not then have been granted or conceptualized in the same way, John Dryden wrote in 1668:

Is it not evident, in these last hundred years (when the Study of Philosophy has been the business of all the Virtuosi in Christendome) that almost a new Nature has been revealed to us? That more errors of the School [that is, of the medieval scholastic thinkers and followers of Thomas Aquinas, generally called Schoolmen] have been detected, more useful Experiments in Philosophy have been made, more Noble Secrets in Opticks, Medicine, Anatomy, Astronomy, discovered than in all those credulous and doting Ages from Aristotle to us? So

true it is that nothing spreads more fast than Science, when rightly and generally cultivated.

To cite one of the twentieth century's most celebrated philosophers, A. N. Whitehead claimed, in Science and the Modern World, that "a brief, and sufficiently accurate description of the intellectual life of the European races during the succeeding two centuries and a quarter up to our own times is that they have been living upon the accumulated capital of ideas provided for them by the genius of the seventeenth century."

A broader range of views could be cited among historians of science, but few would deny that truly extraordinary changes in concepts of natural order-changes that we continue to recognize today as the familiar bases of modern sensibilities-occurred in seventeenth-century Europe, leading to the enterprise that we call "science," with all attendant benefits, travails, and transformation in our collective lives and societies.

In 1939, Alexander Koyré, the dean of twentieth-century students of the Scientific Revolution, described this seventeenth-century transformation as a "veritable 'mutation' of the human intellect . . . one of the most important,if not the most important, since the invention of the Cosmos by Greek thought." The Scientific evolution, according to the eminent historian Herbert Butterfield (1957), "outshines everything since the rise of Christianity and reduces the Renaissance and Reformation to the rank of mere episodes, mere internal displacements, within the system of medieval Christendom." And, in 1986, historian of science Richard S. Westfall stated: "The Scientific Revolution was the most important 'event' in Western history. . . . For good and for ill, science stands at the center of every dimension of modern life. It has shaped most of the categories in terms of which we think, and in the process has frequently subverted humanistic concepts that

furnished the sinews of our civilization."

In the cartoonish caricature of a "one-line" primer, the Scientific Revolution boasts two philosophical founders of the early seventeenth century-the Englishman Francis Bacon (1561-1626), who touted

observational and experimental methods, and the Frenchman René Descartes (1596-1650), who promulgated the mechanical worldview. Galileo (1564-1642) then becomes the first astoundingly successful practitioner, the man who discovered the moons of Jupiter, rearranged the cosmos with a raft of additional telescopic defenses of Copernicus, and famously proclaimed that the "grand book" of nature-that is, the universe-"is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometrical figures." (Galileo's status as martyr to the Roman Inquisition-for he spent the last nine years of his life under the equivalent of "house arrest," following his forced recantation in 1633-also, and justly, enhances his role as a primary hero of rationality.) But the culmination, both in triumphant practice and in fully formulated methodology, resides in a remarkable conjunction of late-seventeenth-century talent, a generation epitomized and honored with the name of its preeminent leader, Isaac Newton (1642-1727), who enjoyed the good fortune of coexistence with so many other brilliant thinkers and doers, most notably Robert Boyle (1627-1691), Edmund Halley (1656-1742), and Robert Hooke (1635-1703).

As with all caricatures based on simplistic historical models of accreting "betterness" (whether by smoothly accumulating improvement or by discontinuous leaps of progress), and on false dichotomies of a bad "before" replaced by a good "after," this description of the Scientific Revolution cannot survive a careful scrutiny of any major aspect of the standard story. To cite just two objections with pedigrees virtually as long as the conventional formulation itself: First, the break between the supposedly benighted Aristotelianism of medieval and Renaissance scholarship, and the experimental and mechanical reforms of the Scientific Revolution, can be recast as far more continuous, with many key insights and discoveries achieved long before the seventeenth century, and abundantly transmitted across the supposed divide. In an early rebuttal that became almost as well known as the basic case for a discontinuous revolution, the French scholar Pierre Duhem, in the opening years of the twentieth century, published three volumes on Leonardo and his precursors. Here Duhem argued that several cornerstones of the Scientific Revolution had been formulated by Aristotelian scholars in fourteenth-century Paris, and had also become sufficiently familiar and accessible that even the formally ill-educated Leonardo, albeit the most brilliant raw intellect of his (or any other) age, sought out and utilized this work, often struggling with Latin texts that he could only read in a halting fashion, as the foundation for his own views of nature. (Duhem developed his thesis under a complex parti pris of personal belief, including strong nationalistic and Catholic elements, but his predisposing biases, although markedly different from the a priori commitments of historians who built the conventional view, cannot be labeled as stronger or more distorting.)

Second, and in an objection close to the heart of my own persona and chosen profession, the conventional view does seem more than a tad parochial in its nearly exclusive focus on the physical sciences, and upon the kinds of relatively simple problems solvable by controlled experiment and subject to reliable mathematical formulation. What can we say about the sciences of natural history, which underwent equally

extensive and strikingly similar changes in the seventeenth century,

but largely without the explicit benefit of such experimental and mathematical reconstitution? Did students of living (and geological) nature merely act as camp followers, passively catching the reflected beams of victorious physics and astronomy? Or did the Scientific Revolution encompass bigger, and perhaps more elusive, themes only partially and imperfectly rendered by the admitted triumphs of new discovery and discombobulations of old beliefs so evident in seventeenth-century physics and astronomy? (Because these questions intrigue me, and because my own expertise lies in this area, I shall choose my examples almost entirely from this neglected study of the impact of the Scientific Revolution upon natural history.)

I derived much of the framework, and many of the quotations, for this opening section from the long and excellent treatise of H. Floris Cohen (The Scientific Revolution: A Historiographical Inquiry, University of Chicago Press, 1994), a work not so much about the content of the Scientific Revolution as about the construction of the concept by historians. Cohen locates much of the difficulty in defining this episode, or any other major "event" in the history of ideas for that matter, in the complex and elusive nature of change itself. We encounter enough trouble in trying to define and characterize the transformation of clear material entities-the evolution of the human lineage, for example. How shall we treat major changes in our approach to the very nature of knowledge and causality? Cohen writes: "To strike the proper balance between a perception of historical events as relatively continuous or relatively discontinuous has been the historian's task ever since the craft attained maturity in the course of the nineteenth century." The Scientific Revolution becomes so elusive in the enormity of its undeniable impact that Steven Shapin, something of an enfant terrible among conventional academicians, opened his iconoclastic, but much respected, study (The Scientific Revolution, University of Chi...

Présentation de l'éditeur :

Newton's Light

The epitaph czar of Westminster Abbey must have demurred, for the great man's grave does not bear these intended words. But Alexander Pope did write a memorable (and technically even heroic) couplet for the tombstone of his most illustrious contemporary. Biblical parodies, perhaps, could not pass muster in Britain's holiest of holies, both sacred and secular,* for Pope's epitome of a life well lived recalled the first overt order of the ultimate boss:

Nature and Nature's laws lay hid in night:

God said, let Newton be! and all was light.

Pope surely wins first prize for succinctness and rhyme, but we may cite any number of statements from the wisest of his contemporaries to the best of later scholars, all affirming that something truly

special roiled the world of seventeenth-century thinkers, changing the very definitions of knowledge and causality, and achieving a beginning of control over nature (or at least predictability of her ways) that previous centuries had not attained or, for themost part, even sought. Although hard to define, and even denied by some, this transforming period has been awarded the two ultimate verbal accolades by a generally timid profession of academic historians: the definite article for uniqueness, and uppercase designation for importance. Historians generally refer to this watershed of the seventeenth century as the Scientific Revolution.

To cite a key contemporary, a poet rather than a scientist, at least by current disciplinary allocations that would not then have been granted or conceptualized in the same way, John Dryden wrote in 1668:

Is it not evident, in these last hundred years (when the Study of Philosophy has been the business of all the Virtuosi in Christendome) that almost a new Nature has been revealed to us? That more errors of the School [that is, of the medieval scholastic thinkers and followers of Thomas Aquinas, generally called Schoolmen] have been detected, more useful Experiments in Philosophy have been made, more Noble Secrets in Opticks, Medicine, Anatomy, Astronomy, discovered than in all those credulous and doting Ages from Aristotle to us? So

true it is that nothing spreads more fast than Science, when rightly and generally cultivated.

To cite one of the twentieth century's most celebrated philosophers, A. N. Whitehead claimed, in Science and the Modern World, that "a brief, and sufficiently accurate description of the intellectual life of the European races during the succeeding two centuries and a quarter up to our own times is that they have been living upon the accumulated capital of ideas provided for them by the genius of the seventeenth century."

A broader range of views could be cited among historians of science, but few would deny that truly extraordinary changes in concepts of natural order-changes that we continue to recognize today as the familiar bases of modern sensibilities-occurred in seventeenth-century Europe, leading to the enterprise that we call "science," with all attendant benefits, travails, and transformation in our collective lives and societies.

In 1939, Alexander Koyré, the dean of twentieth-century students of the Scientific Revolution, described this seventeenth-century transformation as a "veritable 'mutation' of the human intellect . . . one of the most important,if not the most important, since the invention of the Cosmos by Greek thought." The Scientific evolution, according to the eminent historian Herbert Butterfield (1957), "outshines everything since the rise of Christianity and reduces the Renaissance and Reformation to the rank of mere episodes, mere internal displacements, within the system of medieval Christendom." And, in 1986, historian of science Richard S. Westfall stated: "The Scientific Revolution was the most important 'event' in Western history. . . . For good and for ill, science stands at the center of every dimension of modern life. It has shaped most of the categories in terms of which we think, and in the process has frequently subverted humanistic concepts that

furnished the sinews of our civilization."

In the cartoonish caricature of a "one-line" primer, the Scientific Revolution boasts two philosophical founders of the early seventeenth century-the Englishman Francis Bacon (1561-1626), who touted

observational and experimental methods, and the Frenchman René Descartes (1596-1650), who promulgated the mechanical worldview. Galileo (1564-1642) then becomes the first astoundingly successful practitioner, the man who discovered the moons of Jupiter, rearranged the cosmos with a raft of additional telescopic defenses of Copernicus, and famously proclaimed that the "grand book" of nature-that is, the universe-"is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometrical figures." (Galileo's status as martyr to the Roman Inquisition-for he spent the last nine years of his life under the equivalent of "house arrest," following his forced recantation in 1633-also, and justly, enhances his role as a primary hero of rationality.) But the culmination, both in triumphant practice and in fully formulated methodology, resides in a remarkable conjunction of late-seventeenth-century talent, a generation epitomized and honored with the name of its preeminent leader, Isaac Newton (1642-1727), who enjoyed the good fortune of coexistence with so many other brilliant thinkers and doers, most notably Robert Boyle (1627-1691), Edmund Halley (1656-1742), and Robert Hooke (1635-1703).

As with all caricatures based on simplistic historical models of accreting "betterness" (whether by smoothly accumulating improvement or by discontinuous leaps of progress), and on false dichotomies of a bad "before" replaced by a good "after," this description of the Scientific Revolution cannot survive a careful scrutiny of any major aspect of the standard story. To cite just two objections with pedigrees virtually as long as the conventional formulation itself: First, the break between the supposedly benighted Aristotelianism of medieval and Renaissance scholarship, and the experimental and mechanical reforms of the Scientific Revolution, can be recast as far more continuous, with many key insights and discoveries achieved long before the seventeenth century, and abundantly transmitted across the supposed divide. In an early rebuttal that became almost as well known as the basic case for a discontinuous revolution, the French scholar Pierre Duhem, in the opening years of the twentieth century, published three volumes on Leonardo and his precursors. Here Duhem argued that several cornerstones of the Scientific Revolution had been formulated by Aristotelian scholars in fourteenth-century Paris, and had also become sufficiently familiar and accessible that even the formally ill-educated Leonardo, albeit the most brilliant raw intellect of his (or any other) age, sought out and utilized this work, often struggling with Latin texts that he could only read in a halting fashion, as the foundation for his own views of nature. (Duhem developed his thesis under a complex parti pris of personal belief, including strong nationalistic and Catholic elements, but his predisposing biases, although markedly different from the a priori commitments of historians who built the conventional view, cannot be labeled as stronger or more distorting.)

Second, and in an objection close to the heart of my own persona and chosen profession, the conventional view does seem more than a tad parochial in its nearly exclusive focus on the physical sciences, and upon the kinds of relatively simple problems solvable by controlled experiment and subject to reliable mathematical formulation. What can we say about the sciences of natural history, which underwent equally

extensive and strikingly similar changes in the seventeenth century,

but largely without the explicit benefit of such experimental and mathematical reconstitution? Did students of living (and geological) nature merely act as camp followers, passively catching the reflected beams of victorious physics and astronomy? Or did the Scientific Revolution encompass bigger, and perhaps more elusive, themes only partially and imperfectly rendered by the admitted triumphs of new discovery and discombobulations of old beliefs so evident in seventeenth-century physics and astronomy? (Because these questions intrigue me, and because my own expertise lies in this area, I shall choose my examples almost entirely from this neglected study of the impact of the Scientific Revolution upon natural history.)

I derived much of the framework, and many of the quotations, for this opening section from the long and excellent treatise of H. Floris Cohen (The Scientific Revolution: A Historiographical Inquiry, University of Chicago Press, 1994), a work not so much about the content of the Scientific Revolution as about the construction of the concept by historians. Cohen locates much of the difficulty in defining this episode, or any other major "event" in the history of ideas for that matter, in the complex and elusive nature of change itself. We encounter enough trouble in trying to define and characterize the transformation of clear material entities-the evolution of the human lineage, for example. How shall we treat major changes in our approach to the very nature of knowledge and causality? Cohen writes: "To strike the proper balance between a perception of historical events as relatively continuous or relatively discontinuous has been the historian's task ever since the craft attained maturity in the course of the nineteenth century." The Scientific Revolution becomes so elusive in the enormity of its undeniable impact that Steven Shapin, something of an enfant terrible among conventional academicians, opened his iconoclastic, but much respected, study (The Scientific Revolution, University of Chi...

In his ?nal book and his ?rst full-length original title since Full House in 1996, the eminent paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould offers a surprising and nuanced study of the complex relationship between our two great ways of knowing: science and the humanities, twin realms of knowledge that have been divided against each other for far too long. In building his case, Gould shows why the common assumption of an inescapable conflict between science and the humanities is false, mounts a spirited rebuttal to the ideas that his intellectual rival E. O. Wilson set forth in his book Consilience, and explains why the pursuit of knowledge must always operate upon the bedrock of nature’s randomness. The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox is a controversial discourse, rich with facts and observations gathered by one of the most erudite minds of our time.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurJonathan Cape Ltd

- Date d'édition2003

- ISBN 10 022406309X

- ISBN 13 9780224063098

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages288

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 24,90

Frais de port :

EUR 4,67

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister's Pox Mending the Gap Between Science and the Humanities

Edité par

Harmony Books

(2003)

ISBN 10 : 022406309X

ISBN 13 : 9780224063098

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre hardcover. Etat : New. Illustrated (illustrateur). N° de réf. du vendeur 221109004

Acheter neuf

EUR 24,90

Autre devise