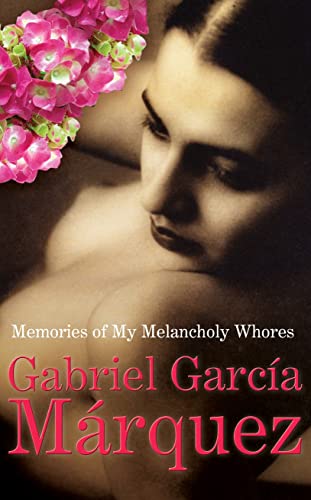

Articles liés à Memories Of My Melancholy Whores

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

The year I turned ninety, I wanted to give myself the gift of a night of wild love with an adolescent virgin. I thought of Rosa Cabarcas, the owner of an illicit house who would inform her good clients when she had a new girl available. I never succumbed to that or to any of her many other lewd temptations, but she did not believe in the purity of my principles. Morality, too, is a question of time, she would say with a malevolent smile, you’ll see. She was a little younger than I, and I hadn’t heard anything about her for so many years that she very well might have died. But after the first ring I recognized the voice on the phone, and with no preambles I fired at her:

“Today’s the day.”

She sighed: Ah, my sad scholar, you disappear for twenty years and come back only to ask for the impossible. She regained mastery of her art at once and offered me half a dozen delectable options, but all of them, to be frank, were used. I said no, insisting the girl had to be a virgin and available that very night. She asked in alarm: What are you trying to prove? Nothing, I replied, wounded to the core, I know very well what I can and cannot do. Unmoved, she said that scholars may know it all, but they don’t know everything: The only Virgos left in the world are people like you who were born in August. Why didn’t you give me more time? Inspiration gives no warnings, I said. But perhaps it can wait, she said, always more knowledgeable than any man, and she asked for just two days to make a thorough investigation of the market. I replied in all seriousness that in an affair such as this, at my age, each hour is like a year. Then it can’t be done, she said without the slightest doubt, but it doesn’t matter, it’s more exciting this way, what the hell, I’ll call you in an hour.

I don’t have to say it because people can see it from leagues away: I’m ugly, shy, and anachronistic. But by dint of not wanting to be those things I have pretended to be just the opposite. Until today, when I have resolved to tell of my own free will just what I’m like, if only to ease my conscience. I have begun with my unusual call to Rosa Cabarcas because, seen from the vantage point of today, that was the beginning of a new life at an age when most mortals have already died.

I live in a colonial house, on the sunny side of San Nicolás Park, where I have spent all the days of my life without wife or fortune, where my parents lived and died, and where I have proposed to die alone, in the same bed in which I was born and on a day that I hope will be distant and painless. My father bought the house at public auction at the end of the nineteenth century, rented the ground floor for luxury shops to a consortium of Italians, and reserved for himself the second floor, where he would live in happiness with one of their daughters, Florina de Dios Cargamantos, a notable interpreter of Mozart, a multilingual Garibaldian, and the most beautiful and talented woman who ever lived in the city: my mother.

The house is spacious and bright, with stucco arches and floors tiled in Florentine mosaics, and four glass doors leading to a wraparound balcony where my mother would sit on March nights to sing love arias with other girls, her cousins. From there you can see San Nicolás Park, the cathedral, and the statue of Christopher Columbus, and beyond that the warehouses on the river wharf and the vast horizon of the Great Magdalena River twenty leagues distant from its estuary. The only unpleasant aspect of the house is that the sun keeps changing windows in the course of the day, and all of them have to be closed when you try to take a siesta in the torrid half-light. When I was left on my own, at the age of thirty-two, I moved into what had been my parents’ bedroom, opened a doorway between that room and the library, and began to auction off whatever I didn’t need to live, which turned out to be almost everything but the books and the Pianola rolls.

For forty years I was the cable editor at El Diario de La Paz, which meant reconstructing and completing in indigenous prose the news of the world that we caught as it flew through sidereal space on shortwaves or in Morse code. Today I scrape by on my pension from that extinct profession, get by even less on the one I receive for having taught Spanish and Latin grammar, earn almost nothing from the Sunday column I’ve written without flagging for more than half a century, and nothing at all from the music and theater pieces published as a favor to me on the many occasions when notable performers come to town. I have never done anything except write, but I don’t possess the vocation or talents of a narrator, have no knowledge at all of the laws of dramatic composition, and if I have embarked upon this enterprise it is because I trust in the light shed by how much I have read in my life. In plain language, I am the end of a line, without merit or brilliance, who would have nothing to leave his descendants if not for the events I am prepared to recount, to the best of my ability, in these memories of my great love.

On my ninetieth birthday I woke, as always, at five in the morning. Since it was Friday, my only obli- gation was to write the signed column published on Sundays in El Diario de La Paz. My symptoms at dawn were perfect for not feeling happy: my bones had been aching since the small hours, my asshole burned, and thunder threatened a storm after three months of drought. I bathed while the coffee was brewing, drank a large cup sweetened with honey, had two pieces of cassava bread, and put on the linen coverall I wear in the house.

The subject of that day’s column, of course, was my ninetieth birthday. I never have thought about age as a leak in the roof indicating the quantity of life one has left to live. When I was very young I heard someone say that when people die the lice nesting in their hair escape in terror onto the pillows, to the shame of the family. That was so harsh a warning to me that I let my hair be shorn for school, and the few strands I have left I still wash with the soap you would use on a grateful fleabitten dog. This means, I tell myself now, that ever since I was little my sense of social decency has been more developed than my sense of death.

For months I had anticipated that my birthday column would not be the usual lament for the years that were gone, but just the opposite: a glorification of old age. I began by wondering when I had become aware of being old, and I believe it was only a short time before that day. At the age of forty-two I had gone to see the doctor about a pain in my back that interfered with my breathing. He attributed no importance to it: That kind of pain is natural at your age, he said.

“In that case,” I said, “what isn’t natural is my age.”

The doctor gave me a pitying smile. I see that you’re a philosopher, he said. It was the first time I thought about my age in terms of being old, but it didn’t take me long to forget about it. I became accustomed to waking every day with a different pain that kept changing location and form as the years passed. At times it seemed to be the clawing of death, and the next day it would disappear. This was when I heard that the first symptom of old age is when you begin to resemble your father. I must be condemned to eternal youth, I thought, because my equine profile will never look like my father’s raw Caribbean features or my mother’s imperial Roman ones. The truth is that the first changes are so slow they pass almost unnoticed, and you go on seeing yourself as you always were, from the inside, but others observe you from the outside.

In my fifth decade I had begun to imagine what old age was like when I noticed the first lapses of memory. I would turn the house upside down looking for my glasses until I discovered that I had them on, or I’d wear them into the shower, or I’d put on my reading glasses over the ones I used for distance. One day I had breakfast twice because I forgot about the first time, and I learned to recognize the alarm in my friends when they didn’t have the courage to tell me I was recounting the same story I had told them a week earlier. By then I had a mental list of faces I knew and another list of the names that went with each one, but at the moment of greeting I didn’t always succeed in matching the faces to the names.

My sexual age never worried me because my powers did not depend so much on me as on women, and they know the how and the why when they want to. Today I laugh at the eighty-year-old youngsters who consult the doctor, alarmed by these sudden shocks, not knowing that in your nineties they’re worse but don’t matter anymore: they are the risks of being alive. On the other hand, it is a triumph of life that old people lose their memories of inessential things, though memory does not often fail with regard to things that are of real interest to us. Cicero illustrated this with the stroke of a pen: No old man forgets where he has hidden his treasure.

With these reflections, and several others, I had finished a first draft of my column when the August sun exploded among the almond trees in the park, and the riverboat that carried the mail, a week late because of the drought, came bellowing into the port canal. I thought: My ninetieth birthday is arriving. I’ll never know why, and don’t pretend to, but it was under the magical effect of that devastating evocation that I decided to call Rosa Cabarcas for help in celebrating my birthday with a libertine night. I’d spent years at holy peace with my body, devoting my time to the erratic rereading of my classics and to my private programs of concert music, but m...

"Marquez describes this amorous, sometimes disturbing journey with the grace and vigour of a master storyteller" (Eithne Farry Daily Mail)

"[A] tender fantasy of loneliness, hope and redemption...this enchanting little book adds another layer to his unhurried fictional world" (Angel Gurria-Quintana Financial Times)

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurJonathan Cape

- Date d'édition2005

- ISBN 10 0224077643

- ISBN 13 9780224077644

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Nombre de pages128

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 9,33

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Memories Of My Melancholy Whores - Garcia Marquez - London

Description du livre Etat : New. Libro nuevo, sellado, fisico, original. Enviamos a todos el mundo por USPS, Fedex y DHL. 100% garantia en su compra. Sealed, new. Unopened. 100%guarentee. We ship worldwide. N° de réf. du vendeur KIRKER141328

Memories of My Melancholy Whores

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.62. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-0224077643