Articles liés à The Music Room

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBN

Extrait :

The school assembly hall was closed for renovations and on Sundays we walked to a church for our weekly service. We spread rumours along pews and daydreamed through sermons until one visiting preacher secured our attention by hoisting a bag onto the pulpit rim — a scuffed black leather bag with accordion pleats at each end, a bag a doctor might take on night visits — and unpacking metal stands and clamps we recognized from science labs, and various jars and packages he ranged along the shelf in front of him. He was in his fifties, dressed in a grey suit and a black shirt with a white dog collar, and he didn’t say anything while preparing his equipment, tightening a clamp on a retort stand, fixing a cardboard tube between the jaws. He struck a match; a fuse caught and sizzled; he shook the match out and stepped back to watch the flame. Then we understood that what he’d clamped to the stand was a firework. The tube flared with a soft, liquid rush, sparks and white embers falling to the stone floor, the preacher’s spectacles glinting in the brightness. The fountain died with a last sputter like someone clearing their throat, the after-image burning in our eyes.

‘Light,’ the preacher said.

_

Our house was almost seven hundred years old, a medieval beginning transformed in the sixteenth century into a Tudor stately home, a castle surrounded by a broad moat, with woods, farmland and a landscaped park on the far side, and a gatehouse tower guarding the two-arched stone bridge, the island’s only point of access and departure.

The gatehouse doors hung on rusty iron hinges, grids of sun-bleached vertical and cross beams like the gates of an ancient city, a Troy or Jericho, creaking like ships as you manoeuvred them. I pushed my hand deep into the keyhole to feel the lock tumblers, and climbed the waffle pattern of oak beams until my strength gave out; I imagined cauldrons of boiling oil tipped through the trapdoor on intruders; I gazed up at the flagpole turret, a canvas flag of blue and white quadrants, gold lions and black moles and chevrons rippling overhead, jackdaws clacking like snooker balls.

When the gates were closed it was as if the house had picked up a shield, but they were almost always open. My father worried for the strength of the hinges and didn’t want to stress them. The gatehouse was a rugged keep with arrowslit windows and a spiral staircase of cold stone that turned through zones of light and shadow to a leaded roof, the moat far below, a heron stooped like an Anglepoise on the near bank, moorhens legging it across the grass. My mother painted Turtle and Pearce flag bunting on the parquet floor by the upright piano; my father carried the new flag up the gatehouse stairs; I followed him onto the roof, watching as he propped the ladder against turret battlements and began to climb. He attached the flag by duffel-coat toggles and when he raised it the canvas unfurled with flame-like rip and putter, blue and white quarters flush to the wind.

_

Richard was the eldest, eleven years older than me, eighteen months older than Martin and Susannah, the twins. My father’s parents had died within ten days of each other not long before I was born, and my family had moved from their village house to the estate passed down through my father’s ancestors since the fourteenth century.

Beyond the churchyard a path of irregular flagstones joined by seams of moss and grass led past the orchard to the road, a wrought-iron gate hanging off-kilter on the far side. Sometimes I opened the gate and took the gravel path uphill through a scrubby wasteland district of nettles and elder bushes. The country flattened off and you came to a stockade of iron railings tipped with spear-points, a kissing-gate that groaned when you disturbed it. The graveyard backed into farmland, a sea of wheat pressing against the railings, trees busy with wrens and chaffinches on the other three sides, floral tributes slumped against the headstones. My grandparents and great-uncles and aunts were buried here; a newer stone beside them marked the grave of my brother Thomas, too soon for lichens or mosses to have got started.

My father kept a black-and-white photograph of him in a leather frame by his bed, and another next to the lamp on his desk; my mother had the same photograph under the glass top of her dressing-table: a boy standing on a hillside, not quite three years old, hair teased by wind, hands clasped in front of his chest, looking away into unrevealed distances. He looked like both of my brothers and me, all at once. Sometimes I stood close to the photograph — I was always careful not to touch it — and concentrated on Thomas, looking for small changes in his expression, trying to imagine him in three dimensions, walking into the kitchen or across the lawn. I wanted to hear his voice.

I knew what had happened, though no one had told me directly. I must have pieced it together from different sources, conversations I’d overheard, my mother or father describing the event to others: a horse, a road, a car passing. When people pointed to the photograph and asked me who it was, I said it was my brother, Thomas, and that I never knew him, he died two years before I was born. I didn’t understand why they said they were sorry. I knew it was a loss, but I couldn’t feel it as one. He was a presence to me, not something taken away.

_

I played in a room at the east end of the house, the moat immediately outside. On clear mornings light bounced off the water through the windows, the white ceiling suddenly unstable with ripples and wind-stir, the surface of the moat reproduced in sunlight overhead. Our new freezer had just been delivered, and I’d got the cardboard box to customize into a secret house, a hatch cut into one side. My father was at work, dog-eared maps and his battered lunch tin on the passenger seat, and my mother was showing a group of history students round the house, so Patsy was here to keep an eye on me and Richard. I liked the threshold moments of crawling into or out of the den, the clement burrow darkness inside the box, the smell of cardboard, the enticing privacy and warmth. Lying on my back I could look through a crack in the roof and watch the ceiling’s imitation of water.

Patsy tried to interest Richard in a book but he was restless, brooding, pacing the room. He noticed a pair of moorhens paddling close to the window and shouted at them — ‘Shoo!’ — as if they’d insulted him, and that eruption seemed to nudge the whole morning off its rails, because Rich stood there with both arms held out like a scarecrow’s, his eyes half-closed, lids fluttering, as if there were static electricity in his eyelashes that made them flicker in and out of each other. His arms began to jerk; he turned round on the spot with his arms held out, jolting; the room went sludgy, as if a spell had swung us out of orbit and everything was slowing down — as if Patsy and I existed in our own current of time and were moving past Richard on a raft, keeping our eyes fixed on him. The spell lasted less than twenty seconds, and as he came through it he lowered his arms to his sides and saw both of us looking intently at him.

‘What?’ he said.

_

I was four when a local school performed Twelfth Night in our garden. A tiered, covered stand went up on the back lawn opposite the yew tree; stagehands rigged up lights and jammed the door on a writhe of power cables. The moat that ran along two sides of the lawn was now the sea around Illyria. Actors emerged from the water and dragged themselves onto dry land after the shipwreck. A spotlight picked out Feste standing on the flat roof above the bathroom on the east stairs. Malvolio’s prison was a wooden cage fitted precisely to my square sandpit.

The drawing room’s French windows opened onto an iron balcony where my father hung the bird-feeders. The stone that anchored the balcony was crumbling and we all knew better than to trust our weight to it. The play started after my bedtime, but the July nights were hot and my parents had left the windows open: I could hear the actors’ voices, the audience laughing at mix-ups and pretensions; I slipped out of bed and crept across the landing, edging on all fours into the windows to watch through the ironwork.

The following summer the Banbury Cross Players performed A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Each night I lay awake listening to the applause as Bottom and his crew approached in the punt and disembarked by the young copper beech in the corner. I couldn’t sleep. I crawled across the landing and up the two carpeted steps to take my place at the balcony, a full moon spinning up like a cue-ball as Oberon and Titania summoned spirits from the shadows. The rustic players reappeared in the punt, Peter Quince holding a lantern at the prow.

I was walking across that lawn with my mother when Dad appeared in the open windows and called out to us, ‘Hold on one second.’

‘Why?’ I said.

‘Keep your eyes on the window.’

He vanished. Mum and I watched the dark gap in the wall. Nothing happened, and I didn’t understand why my father had made us stop, but then a blackbird shot from the side of the house, Dad appearing behind it, smiling, his arms spread like an impresario’s, as if he’d just conjured the bird into existence.

A white china owl sat on a table next to the windows, the first thing I looked for when I pushed through the door from the landing. I came up the spiral staircase calling for my mother and father. I could hear voices. I went straight in, ready for the white owl. Richard was lying on the rug, on his back, his head close to the windows. My mother was kneeling beside him; my father stood next to her, leaning over. I stopped in the doorway. Richard wasn’t moving. He lay rigid, his feet pointing up at the c...

Présentation de l'éditeur :

‘Light,’ the preacher said.

_

Our house was almost seven hundred years old, a medieval beginning transformed in the sixteenth century into a Tudor stately home, a castle surrounded by a broad moat, with woods, farmland and a landscaped park on the far side, and a gatehouse tower guarding the two-arched stone bridge, the island’s only point of access and departure.

The gatehouse doors hung on rusty iron hinges, grids of sun-bleached vertical and cross beams like the gates of an ancient city, a Troy or Jericho, creaking like ships as you manoeuvred them. I pushed my hand deep into the keyhole to feel the lock tumblers, and climbed the waffle pattern of oak beams until my strength gave out; I imagined cauldrons of boiling oil tipped through the trapdoor on intruders; I gazed up at the flagpole turret, a canvas flag of blue and white quadrants, gold lions and black moles and chevrons rippling overhead, jackdaws clacking like snooker balls.

When the gates were closed it was as if the house had picked up a shield, but they were almost always open. My father worried for the strength of the hinges and didn’t want to stress them. The gatehouse was a rugged keep with arrowslit windows and a spiral staircase of cold stone that turned through zones of light and shadow to a leaded roof, the moat far below, a heron stooped like an Anglepoise on the near bank, moorhens legging it across the grass. My mother painted Turtle and Pearce flag bunting on the parquet floor by the upright piano; my father carried the new flag up the gatehouse stairs; I followed him onto the roof, watching as he propped the ladder against turret battlements and began to climb. He attached the flag by duffel-coat toggles and when he raised it the canvas unfurled with flame-like rip and putter, blue and white quarters flush to the wind.

_

Richard was the eldest, eleven years older than me, eighteen months older than Martin and Susannah, the twins. My father’s parents had died within ten days of each other not long before I was born, and my family had moved from their village house to the estate passed down through my father’s ancestors since the fourteenth century.

Beyond the churchyard a path of irregular flagstones joined by seams of moss and grass led past the orchard to the road, a wrought-iron gate hanging off-kilter on the far side. Sometimes I opened the gate and took the gravel path uphill through a scrubby wasteland district of nettles and elder bushes. The country flattened off and you came to a stockade of iron railings tipped with spear-points, a kissing-gate that groaned when you disturbed it. The graveyard backed into farmland, a sea of wheat pressing against the railings, trees busy with wrens and chaffinches on the other three sides, floral tributes slumped against the headstones. My grandparents and great-uncles and aunts were buried here; a newer stone beside them marked the grave of my brother Thomas, too soon for lichens or mosses to have got started.

My father kept a black-and-white photograph of him in a leather frame by his bed, and another next to the lamp on his desk; my mother had the same photograph under the glass top of her dressing-table: a boy standing on a hillside, not quite three years old, hair teased by wind, hands clasped in front of his chest, looking away into unrevealed distances. He looked like both of my brothers and me, all at once. Sometimes I stood close to the photograph — I was always careful not to touch it — and concentrated on Thomas, looking for small changes in his expression, trying to imagine him in three dimensions, walking into the kitchen or across the lawn. I wanted to hear his voice.

I knew what had happened, though no one had told me directly. I must have pieced it together from different sources, conversations I’d overheard, my mother or father describing the event to others: a horse, a road, a car passing. When people pointed to the photograph and asked me who it was, I said it was my brother, Thomas, and that I never knew him, he died two years before I was born. I didn’t understand why they said they were sorry. I knew it was a loss, but I couldn’t feel it as one. He was a presence to me, not something taken away.

_

I played in a room at the east end of the house, the moat immediately outside. On clear mornings light bounced off the water through the windows, the white ceiling suddenly unstable with ripples and wind-stir, the surface of the moat reproduced in sunlight overhead. Our new freezer had just been delivered, and I’d got the cardboard box to customize into a secret house, a hatch cut into one side. My father was at work, dog-eared maps and his battered lunch tin on the passenger seat, and my mother was showing a group of history students round the house, so Patsy was here to keep an eye on me and Richard. I liked the threshold moments of crawling into or out of the den, the clement burrow darkness inside the box, the smell of cardboard, the enticing privacy and warmth. Lying on my back I could look through a crack in the roof and watch the ceiling’s imitation of water.

Patsy tried to interest Richard in a book but he was restless, brooding, pacing the room. He noticed a pair of moorhens paddling close to the window and shouted at them — ‘Shoo!’ — as if they’d insulted him, and that eruption seemed to nudge the whole morning off its rails, because Rich stood there with both arms held out like a scarecrow’s, his eyes half-closed, lids fluttering, as if there were static electricity in his eyelashes that made them flicker in and out of each other. His arms began to jerk; he turned round on the spot with his arms held out, jolting; the room went sludgy, as if a spell had swung us out of orbit and everything was slowing down — as if Patsy and I existed in our own current of time and were moving past Richard on a raft, keeping our eyes fixed on him. The spell lasted less than twenty seconds, and as he came through it he lowered his arms to his sides and saw both of us looking intently at him.

‘What?’ he said.

_

I was four when a local school performed Twelfth Night in our garden. A tiered, covered stand went up on the back lawn opposite the yew tree; stagehands rigged up lights and jammed the door on a writhe of power cables. The moat that ran along two sides of the lawn was now the sea around Illyria. Actors emerged from the water and dragged themselves onto dry land after the shipwreck. A spotlight picked out Feste standing on the flat roof above the bathroom on the east stairs. Malvolio’s prison was a wooden cage fitted precisely to my square sandpit.

The drawing room’s French windows opened onto an iron balcony where my father hung the bird-feeders. The stone that anchored the balcony was crumbling and we all knew better than to trust our weight to it. The play started after my bedtime, but the July nights were hot and my parents had left the windows open: I could hear the actors’ voices, the audience laughing at mix-ups and pretensions; I slipped out of bed and crept across the landing, edging on all fours into the windows to watch through the ironwork.

The following summer the Banbury Cross Players performed A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Each night I lay awake listening to the applause as Bottom and his crew approached in the punt and disembarked by the young copper beech in the corner. I couldn’t sleep. I crawled across the landing and up the two carpeted steps to take my place at the balcony, a full moon spinning up like a cue-ball as Oberon and Titania summoned spirits from the shadows. The rustic players reappeared in the punt, Peter Quince holding a lantern at the prow.

I was walking across that lawn with my mother when Dad appeared in the open windows and called out to us, ‘Hold on one second.’

‘Why?’ I said.

‘Keep your eyes on the window.’

He vanished. Mum and I watched the dark gap in the wall. Nothing happened, and I didn’t understand why my father had made us stop, but then a blackbird shot from the side of the house, Dad appearing behind it, smiling, his arms spread like an impresario’s, as if he’d just conjured the bird into existence.

A white china owl sat on a table next to the windows, the first thing I looked for when I pushed through the door from the landing. I came up the spiral staircase calling for my mother and father. I could hear voices. I went straight in, ready for the white owl. Richard was lying on the rug, on his back, his head close to the windows. My mother was kneeling beside him; my father stood next to her, leaning over. I stopped in the doorway. Richard wasn’t moving. He lay rigid, his feet pointing up at the c...

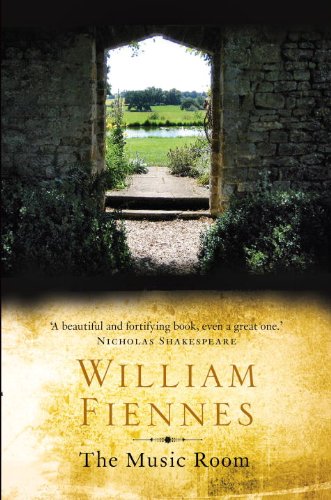

The house was alive with secrets and history, its vaulted passageways, Great Hall and extensive grounds the setting for theatrical presentations, local fairs and international film shoots. Equally fascinating to young Will was his eldest brother Richard, who suffered from disabling epilepsy. The ebbs and flows of electricity in Richard’s brain, along with the mood swings and outbursts caused by the damage his brain sustained, created the rhythm of family life; Richard’s story inspires Fiennes’ journey towards an understanding of the mind. This is a song of home, of an adored and sometimes feared brother and of the miracle of consciousness. Bursting with tender detail, with humour, pathos and wisdom, The Music Room is a sensuous tribute to place, to memory, to the permanence of love and the ache of loss.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurNorton

- Date d'édition2009

- ISBN 10 0307357864

- ISBN 13 9780307357861

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Nombre de pages224

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 115,84

Frais de port :

EUR 21,47

De Canada vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

The Music Room Fiennes, William

Edité par

Random House Canada

(2009)

ISBN 10 : 0307357864

ISBN 13 : 9780307357861

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur XDE--335

Acheter neuf

EUR 115,84

Autre devise