Articles liés à My Lobotomy: A Memoir

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

June

This much I know for sure: I was born in Peralta Hospital in Oakland, California, on November 30, 1948. My parents were Rodney Lloyd Dully and June Louise Pierce Dully. I was their first child, and they named me Howard August Dully, after my father’s father. Rodney was twenty-three. June was thirty-four.

They had been married less than a year. Their wedding was held on Sunday, December 28, 1947, three days after Christmas, at one o’clock in the afternoon, at the Westminster Presbyterian Church in Sacramento, California. The wedding photographs show an eager, nervous couple. He’s in white tie and tails, with a white carnation in his lapel. She’s in white satin, and a veil decorated with white flowers. They are both dark-haired and dark-eyed. Together they are cutting the cake—staring at the cake, not at each other—and smiling.

A reception followed at 917 Forty-fifth Street, at the home of my mother’s uncle Ross and aunt Ruth Pierce. My father’s mother attended. So did his two brothers. One of them, his younger brother, Kenneth, wore a tuxedo all the way up from San Jose on the train.

My father’s relatives were railroad workers and lumberjack types from the area around Chehalis and Centralia, Washington. My dad spent his summers in a lumber camp with one of his uncles. They were logging people.

My father’s father was an immigrant, born in 1899 in a place called Revel, Estonia, in what would later be the Soviet Union. When he left Estonia, his name was August Tulle. When he got to America, where he joined his brothers, Alexander and John— he had two sisters, Marja and Lovisa, whom he left behind in Estonia—he was called August Dully. He later added the first name Howard, because it sounded American to him.

My father’s mother was the child of immigrants from Ireland. She was born Beulah Belle Cowan in Litchfield, Michigan, in 1902. Her family later moved to Portland, Oregon, in time for Beulah to attend high school, where she was so smart she skipped two grades.

August went to Portland, too, because that’s where his brothers were. According to his World War I draft registration card, he was brown-haired, blue-eyed, and of medium height. He got work as a window dresser for the Columbia River Ship Company. He became a mason. He met the redheaded Beulah at a dance. She told her mother that night, “I just met the man I’m going to marry.” She was sixteen. A short while later, they tied the knot and took a freighter to San Francisco for their honeymoon, and stayed. A 1920 U.S. Census survey shows them living in an apartment building on Fourth Street. Howard A. Dully was now a naturalized citizen, working as a laborer in the shipyards.

Sometime after, they moved to Washington, where my grandfather went to work on the railroads. They started having sons—Eugene, Rodney, and Kenneth—before August got sick with tuberculosis. Beulah believed he caught it on that freighter going to San Francisco. He died at home, in bed, on New Year’s Day, 1929. My dad was three years old. His baby brother was only fourteen months old.

Beulah Belle never remarried. She was hardheaded and strong-willed. She said, “I will never again have a man tell me what to do.”

But she had a hard time taking care of her family. She couldn’t keep up payments on the house. When she lost it, the boys went to stay with relatives. My dad was sent to live with an aunt and uncle at age six, and was shuffled from place to place after that. By his own account, he lived in six different cities before he finished high school—born in Centralia, Washington; then shipped around Oregon to Marshfield, Grants Pass, Medford, and Eugene; then to Ryderwood, Washington, where he and his brother Kenneth lived in a logging camp with their former housekeeper Evelyn Townsend and her husband, Orville Black.

At eighteen, Rod left Washington to serve with the U.S. Army, enlisting in San Francisco on December 9, 1943. Though he later was reluctant to talk about it, I know from my uncles that he was sent overseas and stationed in France. He served with the 723rd Railroad Division, laying track in an area near L’Aigle, France, that was surrounded by mines. One of my uncles told me that my father never recovered from the war. He said, “The man who went away to France never came back. He was damaged by what he saw there.”

But another of my uncles told me Rod bragged about having a German girlfriend, so I guess it wasn’t all bad. Not as bad as his brother Gene, who joined the army and got sent to Australia and New Guinea, where he developed malaria and tuberculosis and almost died. He weighed one hundred pounds when he came back to America, and lived at a military hospital in Livermore, California, for a long time after that.

By the time Rod finished his military service, his mother had left her job with Western Union Telegraph, in the Northwest, and moved to Oakland to work for the Southern Pacific Railroad. She was later made a night supervisor, working in the San Francisco office on Market Street. She would still be working there when I was born.

My mother’s folks came from the other end of the economic spectrum. June was the daughter of Daisy Seulberger and Hubert O. Pierce—German on her mother’s side, English on her father’s. Daisy grew up weatlthy, married Pierce, and had three children: Gordon, June, and Hugh. When Pierce died, Daisy married Delos Patrician, another wealthy Bay Area businessman. She moved her family to Oakland, into a huge, three-story shingled home on Newton Avenue. June spent her childhood there.

After his military service, my father relocated to the Bay Area and started taking classes at San Francisco Junior College, learning to be a teacher and doing his undergraduate work in elementary education.

Over the summers, he got part-time work at a popular high Sierras vacation spot, Tuolumne Meadows, in Yosemite. He met a young woman there, working as a housekeeper, who captured his eye. Her name was June.

She was tall, dark, and athletic, and for Rod she was a real catch. She was a graduate of the University of California at Berkeley, where she had been active with the Alpha Xi Delta sorority, and had a certificate to teach nursery school. She was from a well-known Oakland family, and for several years she had been a fixture on the local social scene. During the war she had worked in Washington, D.C., as a private secretary to the U.S. congressman from her district. When she returned to Oakland, she often had her name in the newspapers, hosting luncheons and teas for her society friends.

She had been courted by quite a few young men, but her controlling mother, Daisy, drove all the boyfriends away. When she met Rod, June was still beautiful, but she was no longer what you’d call young, especially not at that time. She was thirty-two. Being unmarried at that age during the 1940s was almost like being a spinster.

Their courtship was sudden and passionate. They fell in love over the summer of 1946, and saw each other in San Francisco and Berkeley through the next year. When June returned to work in Yosemite in the summer of ’47, this time at Glen Aulin Camp, Rod left for the lumberyards of northern California and southern Oregon, where he was determined to make enough money to marry June in style. His letters over that summer were eager and filled with love. He was full of plans and promises—for his career, their wedding, the house he would buy her, the family they would have. He was worried that he was not the man June’s mother wanted, or from the right level of society, but he was determined to prove himself. “I expect to make you happy. I won’t marry you and take you into a life you won’t be happy in,” he wrote. “I’m happy now, much happier than I’ve ever been before in my life, cause you’re my little dream girl and my dream is coming true.”

After a hard summer of logging work, the plans for the wedding were made. The ceremony was held three days after Christmas in Sacramento. According to a newspaper story a week later, the couple was “honeymooning in Carmel” after a ceremony in which “the bride wore a white satin gown with a sweetheart neckline, long sleeves ending in points at the wrists and full skirt with a double peplum pointed at the front. Her full-length veil of silk net was attached to a bandeau of seed pearls and orange blossoms. She also carried a handkerchief which has been in her family for 75 years.”

The bride was given away by her uncle Ross, in whose Sacramento house she had been living. The groom’s best man was his brother Kenneth.

According to family stories, some of June’s family objected. Rod was too young for June, Daisy said, and didn’t have good prospects. June may have been uncomfortable with the relative poverty she was marrying into, too. My dad later told people that he got into a fender bender not long after he met June, and that his feelings were hurt when she said she was embarrassed to be seen driving around in his banged-up car.

With a wife to support, my father left school. He and my mother moved up north, to Medford, Oregon, where Rod returned to the lumber business and went to work as a lumber tallyman with the Southern Oregon Sugar Pine Corporation in Central Point, two miles outside of Medford.

Soon the young married couple had a baby on the way—me. Near the end of her term, my mother left my dad in Medford and moved in with her mother in Oakland, a pattern she would repeat for the births of all her children.

If everything had gone as planned, she probably would have returned to Medford and raised a family.

But my father had some bad luck. One morning on a work break he became incoherent and had to be taken by ambulance to a Medford hospital. He was treated for sun stroke and sent back to work. When his symptoms returned, he saw another doctor and was treated for heat stroke. When he still did not improve, Rod left Medford and went to live with June’s family in the big house in Oakland. He recovered but was told not to resume any kind of hard, physical outdoor work. The lumber business was over for him. He would never return to the Northwest.

I was carried to full term, according to the birth records, and I was a normal, healthy child, delivered early in the morning by a doctor named John Henry. I was a big baby—nine pounds and twenty-four inches long. (I come by that naturally. My parents were both big. My mother was six feet and my father was six feet three inches. My younger brother, Brian, is six feet ten inches.) Photo- graphs of me when I was a baby show a big, goofy-looking infant with bright eyes and a healthy appetite. In one picture I am reaching out for a slice of cake. My father says I was a cheerful, happy, friendly baby who was doted upon by his mother.

They gave me my grandfather’s adopted American name—Howard August Dully. To this day my uncle Kenneth says I’m the one Dully who looks most like him.

My father’s occupation was listed on my birth certificate as “Talley man, Southern Sugar Pine Lumber Co., Medford, Ore.” But he never went back to that job. After my birth, he moved his new family into a one-bedroom apartment at Spartan Village, a low-income student-housing complex near San Jose State University. He got a sales job at San Jose Lumber, a lumberyard right down the street from our apartment, and resumed his studies at the university.

I have very few memories of living at Spartan Village. The clearest one is a memory of fear. There was a playground there and my dad built me a choo-choo train out of fifty-gallon oil drums and lumber. I was proud of it, and proud that my dad had built it.

But there was a big, open field of weeds next to the apartment complex. I was afraid of that field. I was afraid of what was in those weeds. There was a low place in the center of the field that kids would run into and disappear. I was afraid they wouldn’t come out. I knew that if I went into that field I would fall in and not be able to come out. It’s the first thing in my life I remember being afraid of.

In August 1951, when I was two and a half years old, Rodney and June had another son. They named him Brian. Like me, he was born healthy. I now had a roommate in our Spartan Village apartment.

In some families, the arrival of the second son is the end of the world for the first son, because now he has to share his mother with a stranger. Not in my family. My dad said Brian’s birth did not have any impact on my close relationship with June. He was responsi- ble for Brian, while she concentrated all her love on me. “I was the one taking care of Brian,” he said. “All she cared about was little Howard.”

My father told me later that I was the most important person in my mother’s life—more important, even, than him. I was the number-one son. “I could’ve dropped dead and it wouldn’t have made a bit of difference,” my dad said. “She had you.”

When he completed his degree, my father was hired as an elementary school teacher in a one-room schoolhouse in a little town called Pollock Pines in the Sierras, about halfway between Sacramento and Lake Tahoe.

Most of my early childhood memories come from this place. Our house sat on a hill that sloped down to a bend in Highway 50, the two-lane road that led from Sacramento to Lake Tahoe. We had a little cocker spaniel named Blackie. He was hit by a car on that road, and killed, when I was about two years old.

I also remember sitting in a coffee shop in Placerville, having a soda with my mother. We were waiting for my father. Music was playing.

My mother’s uncle Ross and aunt Ruth had a huge mountain cabin, so big it was more like a hunting lodge, farther up Highway 50, near a famous old resort called Little Norway. It had been built by my great-grandfather—Grandma Daisy’s father—in the 1930s. The main building, which was two stories and filled with moose heads, was surrounded by pine trees and smaller cabins that were so primitive they had dirt floors. We used to stay in one of them when I was little.

In the winter, the snow was so deep we cut steps in it and climbed onto the cabin roof. Later on I learned to ski there, but my earliest memories of the snow are unhappy ones. I stepped into a snow drift that was so deep I sank in up to my waist and couldn’t get out. This frightened me. I thought some kind of snow monster was going to come and eat me, and I began to cry.

My father thought it was the funniest thing he’d ever seen. I was terrified, but he was laughing. That made me mad at him.

I think I was a happy child. I remember walking the two blocks from our apartment to my father’s work every day, my mother carrying the sack lunch she’d made for him. But I also remember not liking the way my mother made me dress. I had to wear colored shirts, and those little shorts that have straps to hold them up. They looked like those German lederhosen. Even as a kid I thought they were lame. I probably wanted to wear blue jeans.

My mother liked being a mother and she took naturally to it. In my favorite picture of her from that time, she’s wearing a cap-sleeve shirt, a wide black belt, and a billowing skirt, and she’s standing under a clothesline in the Spartan Village yard. She looks like she’s calling to me, and she looks happy.

Family members have told me that she enjoyed life and laughed a lot. She wasn’t serious, like my dad. She was more carefree, and liked to have fun.

In my memory, she was a very loving and indulgent mother. I remember being held and hugged and kissed by her. I remember being loved. I have fleeting pictures in my head of green grass, of sunshine, of running past my mother’s full skirts. I remember her laughing.

My father was ...

—William Grimes, The New York Times

"Dully's tale is a heartbreakingly sad story of a life seriously, tragically interrupted. All Howard Dully wanted was to be normal. His entire life has been a search for normality. He did what he had to do to survive. This book is his legacy, and it is a powerful one."

—San Francisco Chronicle

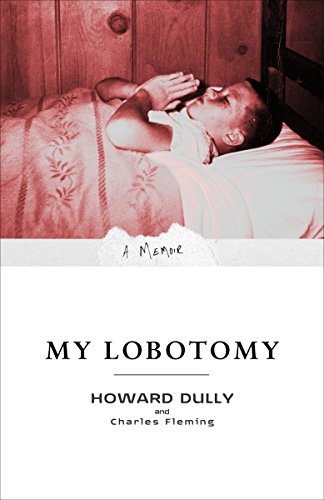

"In My Lobotomy Howard Dully tells more of the story that so many found gripping in a National Public Radio broadcast: how his stepmother joined with a doctor willing to slice into his brain with “ice picks” when he was all of 12 years old."

—New York Daily News

"[Dully's] memoir is vital and almost too disturbing to bear-a piece of recent history that reads like science fiction... Dully, the only patient to ever request his file, speaks eloquently. It’s a voice to crash a server, and to break your heart.”

—Cleveland Plain Dealer

"The value of the book is in the indomitable spirit Dully displays throughout his grueling saga...By coming to grips with his past and shining a light into the dark corners of his medical records, Dully shows that regardless of what happened to his brain, his heart and soul are ferociously strong.”

—Chicago-Sun Times

"Plain-spoken, heart wrenching memoir ..."

—San Jose Mercury News

"Gut-wrenching memoir by a man who was lobotomized at the age of 12.

Assisted by journalist/novelist Fleming (After Havana, 2003, etc.), Dully recounts a family

tragedy whose Sophoclean proportions he could only sketch in his powerful 2005 broadcast on NPR’s

All Things Considered.

“In 1960,” he writes, “I was given a transorbital, or ‘ice pick’ lobotomy. My stepmother arranged it. My father agreed to it. Dr. Walter Freeman, the father of the American lobotomy, told me he was going to do some ‘tests.’ It took ten minutes and cost two hundred dollars.” Fellow doctors called Freeman’s technique barbaric: an ice pick—like instrument was inserted about three inches into each eye socket and twirled to sever connections from the frontal lobe to the rest of the brain. The procedure was intended to help curb a variety of psychoses by muting emotional responses, but sometimes it irreversibly reduced patients to a childlike state or (in 15% of the operations Freeman performed) killed them outright. Dully’s ten-minute “test” did neither, but in some ways it had a far crueler result, since it didn’t end the unruly behavior that had set his stepmother against him to begin with.

“I spent the next forty years in and out of insane asylums, jails, and halfway houses,” he tells us. “I was homeless, alcoholic, and drug-addicted. I was lost.” From all accounts, there was no excuse for the lobotomy. Dully had never been “crazy,” and his (not very) bad behavior sounds like the typical acting-up of a child in desperate need of affection. His stepmother responded with unrelenting abuse and neglect, his father allowed her to demonize his son and never admitted his complicity in the lobotomy; Freeman capitalized on their monumental dysfunction. It’s a tale of epic horror, and while Dully’s courage in telling it inspires awe, readers are left to speculate about what drove supposedly responsible adults to such unconscionable acts.

A profoundly disturbing survivor’s tale."

—Kirkus

"...Hard to put down."

—The Record

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurCrown

- Date d'édition2008

- ISBN 10 0307381277

- ISBN 13 9780307381279

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages304

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,73

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

My Lobotomy: A Memoir

Description du livre Etat : New. Brand New! Not Overstocks or Low Quality Book Club Editions! Direct From the Publisher! We're not a giant, faceless warehouse organization! We're a small town bookstore that loves books and loves it's customers! Buy from Lakeside Books!. N° de réf. du vendeur OTF-S-9780307381279

My Lobotomy: A Memoir

Description du livre Etat : New. Well packaged and promptly shipped from California. Partnered with Friends of the Library since 2010. N° de réf. du vendeur 1LAUHV002I9Z

My Lobotomy: A Memoir by Dully, Howard, Fleming, Charles [Paperback ]

Description du livre Soft Cover. Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780307381279

My Lobotomy: A Memoir (Paperback or Softback)

Description du livre Paperback or Softback. Etat : New. My Lobotomy: A Memoir 0.49. Book. N° de réf. du vendeur BBS-9780307381279

My Lobotomy: A Memoir

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : New. Brand New!. N° de réf. du vendeur 0307381277

My Lobotomy

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 5946493-n

My Lobotomy: A Memoir

Description du livre Etat : New. Book is in NEW condition. N° de réf. du vendeur 0307381277-2-1

My Lobotomy: A Memoir

Description du livre Etat : New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-0307381277-new

My Lobotomy: A Memoir

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur I-9780307381279

My Lobotomy (Paperback)

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Paperback. In this heartfelt memoir from one of the youngest recipients of the transorbital lobotamy, Howard Dully shares the story of a painfully dysfunctional childhood, a misspent youth, his struggle to claim the life that was taken from him, and his redemption.At twelve, Howard Dully was guilty of the same crimes as other boys his age: he was moody and messy, rambunctious with his brothers, contrary just to prove a point, and perpetually at odds with his parents. Yet somehow, this normal boy became one of the youngest people on whom Dr. Walter Freeman performed his barbaric transorbitalor ice picklobotomy.Abandoned by his family within a year of the surgery, Howard spent his teen years in mental institutions, his twenties in jail, and his thirties in a bottle. It wasnt until he was in his forties that Howard began to pull his life together. But even as he began to live the normal life he had been denied, Howard struggled with one question: Why?There were only three people who would know the truth: Freeman, the man who performed the procedure; Lou, his cold and demanding stepmother who brought Howard to the doctors attention; and his father, Rodney. Of the three, only Rodney, the man who hadnt intervened on his sons behalf, was still living. Time was running out. Stable and happy for the first time in decades, Howard began to search for answers.Through his research, Howard met other lobotomy patients and their families, talked with one of Freemans sons about his fathers controversial lifes work, and confronted Rodney about his complicity. And, in the archive where the doctors files are stored, he finally came face to face with the truth.Revealing what happened to a child no onenot his father, not the medical community, not the statewas willing to protect, My Lobotomy exposes a shameful chapter in the history of the treatment of mental illness. Yet, ultimately, this is a powerful and moving chronicle of the life of one man. Dully became, at age 12, one of the youngest victims of the infamous ice-pick lobotomy. The story of his courageous journey to understand why this nightmare happened is told here. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780307381279