Articles liés à Last Man in Tower

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

At each election, when Mumbai takes stock of herself, it is reported that one-fourth of the city’s slums are here, in the vicinity of the airport—and many older Bombaywallahs are sure anything in or around Vakola must be slummy. (They are not sure how you even pronounce it: Va-KHO-la, or VAA-k’-la?) In such a questionable neighbourhood, Vishram Society is anchored like a dreadnought of middle-class respectability, ready to fire on anyone who might impugn the pucca quality of its inhabitants. For years it was the only good building—which is to say, the only registered co-operative society—in the neighbourhood; it was erected as an experiment in gentrification back in the late 1950s, when Vakola was semi-swamp, a few bright mansions amidst mangroves and malarial clouds. Wild boar and bands of dacoits were rumoured to prowl the banyan trees, and rickshaws and taxis refused to come here after sunset. In gratitude to Vishram Society’s pioneers, who defied bandits and anopheles mosquitoes, braved the dirt lane on their cycles and Bajaj scooters, cut down the trees, built a thick compound wall and hung signs in English on it, the local politicians have decreed that the lane that winds down from the main road to the front gate of the building be called “Vishram Society Lane.”

The mangroves are long gone. Other middle-class buildings have come up now—the best of these, so local real-estate brokers say, is Gold Coin Society, but Marigold, Hibiscus, and White Rose grow and grow in reputation—and with the recent arrival of the Grand Hyatt Hotel, a five-star, the area is on the verge of ripening into permanent middle-class propriety. Yet none of this would have been possible without Vishram Society, and the grandmotherly building is spoken of with reverence throughout the neighbourhood.

It is, strictly speaking, two distinct Societies enclosed within the same compound wall. Vishram Society Tower B, which was erected in the late 1970s, stands in the south-east corner of the original plot: seven storeys tall, it is the more desirable building to purchase or rent in, and many young executives who have found work in the nearby Bandra-Kurla financial complex live here with their families.

Tower A is what the neighbours think of as “Vishram Society.” It stands in the centre of the compound, six storeys tall; a marble block set into the gate-post says in weathered lettering:

This plaque was unveiled by Shri Krishna Menon, the honourable defence minister of India, on 14 November 1959, birthday of our beloved prime minister, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru.

Here things become blurry; you must get down on your knees and peer to make out the last lines:

. . . has asked Menon to convey his fondest hope that Vishram Society should serve as an example of “good housing for good Indians.”

Erected by:

Members of the Vishram Society Co-operative Housing Society Fully registered and incorporated in the city of Bombay 14-11-1959

The face of this tower, once pink, is now a rainwater-stained, fungus-licked grey, although veins of primordial pink show wherever the roofing has protected the walls from the monsoon rains. Every flat has iron grilles on the windows: geraniums, jasmines, and the spikes of cacti push through the rusty metal squares. Luxuriant ferns, green and reddish green, blur the corners of some windows, making them look like entrances to small caves.

The more enterprising of the residents have paid for improve- ments to this shabby exterior—hands have scrubbed around some of the windows, creating aureoles on the façade, further complicating the patchwork of pink, mildew-grey, black, cement-grey, rust-brown, fern-green, and floral red, to which, by midday, are added the patterns of bedsheets and saris put out to dry on the grilles and balconies. An old-fashioned building, Vishram has no lobby; you walk into a dark square entranceway and turn to your left (if you are, or are visiting, Mrs. Saldanha of 0C), or climb the dingy stairwell to the homes on the higher floors. (An Otis lift exists, but unreliably so.) Perforated with eight-pointed stars, the wall along the stairwell resembles the screen of the women’s zenana in an old haveli, and hints at secretive, even sinister, goings-on inside.

Outside, parked along the compound wall are a dozen scooters and motorbikes, three Maruti-Suzukis, two Tata Indicas, a battered Toyota Qualis, and a few children’s bicycles. The main feature of this compound is a three-foot-tall polished black-stone cross, set inside a shrine of glazed blue-and-white tiles and covered in fading flowers and wreaths—a reminder that the building was originally meant for Roman Catholics. Hindus were admitted in the late 1960s, and in the 1980s the better kind of Muslim—Bohra, Ismaili, college-educated. Vishram is now entirely “cosmopolitan” (i.e., ethnically and religiously mixed). Diagonally across from the black cross stands the guard’s booth, on whose wall Ram Khare, the Hindu watchman, has stencilled in red a slogan adapted from the Bhagavad Gita:

I was never born and I will never die; I do not hurt and cannot be hurt; I am invincible, immortal, indestructible.

A blue register juts out of the open window of the guard’s booth. A sign hangs from the roof:

All visitors must sign the log book

and provide correct address and mobile phone number before entry

by order—

The Secretary Vishram Co-operative Housing Society

A banyan tree has grown through the compound wall next to the booth. Painted umber like the wall, and speckled with dirt, the stem of the tree bulges from the masonry like a camouflaged leopard; it lends an air of solidity and reliability to Ram Khare’s booth that it perhaps does not deserve.

The compound wall, which is set behind a gutter, has two dusty signs hanging from it:

Visit Speed-Tek Cyber-Café. Proprietor Ibrahim Kudwa

Renaissance Real Estate. Honest and reliable. Near Vakola Market

The evening cricket games of the children of Vishram have left most of the compound bare of any flowering plants, although a clump of hibiscus plants flourishes near the back wall to ward off the stench of raw meat from a beef shop somewhere behind the Society. At night, dark shapes shoot up and down the dim Vishram Society Lane; rats and bandicoots dart like billiard balls struck around the narrow alley, crazed by the mysterious smell of fresh blood.

On Sunday morning, the aroma is of fresh baking. There are Mangalorean stores here that cater to the Christian members of Vishram and other good Societies; on the morning of the Sabbath, ladies in long patterned dresses and girls with powdered faces and silk skirts return- ing from St. Antony Church will crowd these stores for bread and sunnas. In a little while, the smell of boiling broth and spicy chicken wafts out from the opened windows of Vishram Society into the neighbourhood. At such an hour of contentment, the spirit of Prime Minister Nehru, if it were to hover over the building, might well declare itself satisfied.

Yet Vishram’s residents are the first to point out that this Society is nothing like paradise. You know a community by the luxuries it can live without. Those in Vishram dispense with the most basic: self-deception. To any inquiring outsider they will freely admit the humiliations of life in their Society—in their honest frustration, indeed, they may exaggerate these problems.

Number one. The Society, like most buildings in Vakola, does not receive a 24-hour supply of running water. Since it is on the poorer, eastern side of the train tracks, Vakola is blessed only twice a day by the Municipality: water flows in the taps four to six in the morning, and 7:30 p.m. to 9 p.m. The residents have fitted storage tanks above their bathrooms, but these can only hold so much (larger tanks threaten the stability of a building this ancient). By five in the evening the taps have usually run dry; the residents come out to talk. A few minutes after seven thirty, the reviving vascular system of Vishram Society ends all talk; water is coursing at high pressure up the pipes, and kitchens and bathrooms are busy places. The residents know that their evening washing, bathing, and cooking all have to be timed to this hour and a half when the pressure in the taps is the greatest; as do ancillary activities that rely on the easy availability of running water. If the children of Vishram Society could trace a path back to their conceptions, they would generally find that they occurred between half past six and a quarter to eight.

The second problem is the one that all of Santa Cruz, even the good part west of the railway line, is notorious for. Acute at night, it also becomes an issue on Sundays between 7 and 8 a.m. You open your window and there it is: a Boeing 747, flying right over your building. The residents insist that after the first month, the phrase “noise pollution” means nothing to you—and this is probably true—yet rental prices for Vishram Society and its neighbours are at least a fourth lower because of the domestic airport’s proximity.

The final problem, existential in nature, is spelled out by the glass-faced noticeboard:

NOTICE

Vishram Co-operative Hsg Society Ltd, Tower A Minutes of the special meeting held on Saturday, 28 April

Theme: Emergency nature of repa...

—Meera Subramanian, Orion Magazine

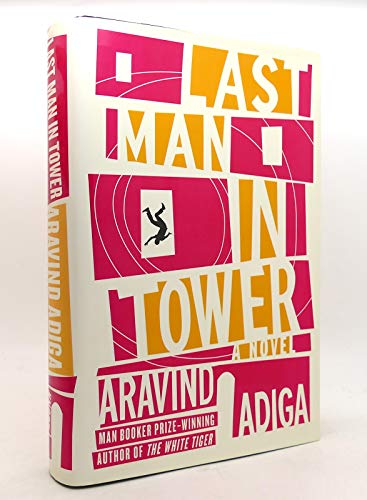

“Vivid. . . A novel written by a Man Booker prize winner [comes with] high expectations, [and] Adiga’s latest Last Man in Tower, does not disappoint. He skillfully builds the backdrop for his story. With few words, he sets the scene of poverty and filth in the slums in sharp contrast to the newfound riches made by some in Mumbai, contrasting the new India and its bright technological future with the last remnants of the British Raj. . . . Graphic and colorful . . . thought-provoking and intense.”

—Christine Morris Campbell, The Decatur Daily

“In the rapidly expanding city of Mumbai, where new buildings sprout like weeds, the construction business isn’t just a front for illegal activity, it’s a raison d’être. When a less-than-ethical developer tries to lure, and later coerce, a community of long-standing tenants out of their apartment complex, it is only the widowed schoolteacher of 3A who continues to rebuff him. In this struggle, Adiga—the author of the Man Booker-winning The White Tiger—maps out in luminous prose India’s ambivalence toward its accelerated growth, while creating an engaging protagonist in the stubborn resident: a man whose ambition and independence have been tempered with an understanding of the important, if almost imperceptible, difference between development and progress. A-”

—Keith Staskiewicz, Entertainment Weekly

“Aravind Adiga, winner of the Man Booker Prize for The White Tiger, brings readers another look at an India at once simple and complex, as old as time and brand new. . . . Adiga has written the story of a New India; one rife with greed and opportunism, underpinned by the daily struggle of millions in the lower classes. This funny and poignant story is multidimensional, layered with many engaging stories and characters, with Masterji as the hero. He is neither Gandhi nor Christ but an unmistakable, irresistible symbol of integrity and quiet perseverance.”

—Valerie Ryan, The Seattle Times

“It sounds far too clinical to say that Aravind Adiga writes about the human condition. He does, but, like any good novelist, Adiga’s story lingers because it nestles in the heart and the head. In Last Man in Tower, his new novel about the perils of gentrification in a Mumbai neighborhood, the plot turns on a developer’s generous offer to convince apartment residents to leave their building so that he can build a luxury tower in its place. The book mines the tricky terrain of the bittersweet and black humor, always teasing out just enough goodness to allow readers a glimmer of hope for humanity. Adiga won the Booker for his debut, The White Tiger, and his new novel shows no signs of a sophomore slump. Last Man in Tower glides along with a sprawling cast of characters, including the teeming city of Mumbai itself. . . . With wit and observation, Adiga gives readers a well-rounded portrait of Mumbai in all of its teeming, bleating, inefficient glory. In one delightful aside, Adiga notes the transition beyond middle age with a zinger of a question: ‘What would he do with his remaining time—the cigarette stub of years left to a man already in his 60s?’ . . . Adiga never settles for the grand epiphany or the tidy conclusion. In a line worthy of John Irving, Adiga writes: ‘A man’s past keeps growing, even when his future has come to a full stop.’”

—Erik Spanberg, Christian Science Monitor

“First-rate. If you loved the movie Slumdog Millionaire, you will inhale the novel Last Man in Tower. Adiga’s second novel is even better than the superb White Tiger. You simply do not realize how anemic most contemporary fiction is until you read Adiga's muscular prose. His plots don't unwind, they surge. [Last Man] tells the story of a small apartment building and its owner occupants, a collection of middle-class Indians—Hindu, Muslim, Catholic. There is love, dislike, bickering, resentment. Most of all, there are genuine human connections. Trouble begins when a real estate mogul decides to build a luxury high-rise where the building currently stands, offer[ing] residents 250 times what their dinky little apartments are worth. The result is chaos . . . life-long friends turn on each other. Money—even the possibility of it—changes everything. What makes [Last Man in Tower] so superb is the way Adiga balances the micro plot—will Masterji agree to sell?—with the macro: How Mumbai is changing in profound, often disturbing ways. Most of all, Last Man in Tower asks the eternal questions: What is right, what is wrong, what do we owe each other, what do we owe ourselves? Just brilliant.”

—Deirdre Donahue, USA Today

“What happens to a man who is not for sale in a society where everyone else has his price? That is the subject of Adiga’s adroit, ruthless and sobering novel. Masterji is sequentially betrayed by neighbors, clergy, friends, lawyers, journalists and even his own grasping son as the reader roots for some deus ex machina to save him. Adiga, who earned the Man Booker prize for White Tiger, peppers his universally relevant tour de force with brilliant touches, multiple ironies and an indictment of our nature.”

—Sheila Anne Feeney, The Star Ledger

“When does the heartfelt convictions of one solitary man negate the jointly held consensus of the rest of any civic society? That is the question posed at the center of Aravind Adiga’s audacious new novel, an impressive and propulsive examination of the struggle for a slice of prime Mumbai real estate. It is a worthy follow-up to Adiga’s Booker Prize novel, White Tiger, as he goes back to the well to explore the changing face of a rapidly growing India. . . . Whether the reader sympathizes with Masterji—who stands in the way of his neighbors’ most audacious dreams, and whose integrity and incorruptibility borders on narcissims—may be equivalent to, say, how each of us felt with the Ralph Nader spoiler in the Bush-Gore election. Was he an honorable man to have taken a stand? Or was he simply an egoist? There is a grudging admiration for Masterji’s stand, mixed with an impatience and frustration at how this high-principled man stubbornly torpedoes the will of the majority. . . . A Dickensian quality pervades this ambitious novel, which fearlessly tackles electrifying themes: what price growth? Will good people risk their humanity when faced with a chance to score a big payday? When does the will of a man who foregoes monetary gain resemble selfishness as opposed to virtue? And who can we trust to stand by us when we take a lone stance? This book of contrasts—between a man of finance and a man of virtue (although, of course, it is not as simple as that) . . . between wealth and squalor . . . between the old and the new is a tour de force. And it is certain to add to Aravind Adiga’s already sterling reputation.”

—Jill I. Shtulman, Mostly Fiction Book Reviews

“We humans are an optimistic lot. We want to believe that things will get better. . . . What would we do if just one old man kept us from fulfilling these dreams? This is the question that dogs the residents of rundown Vishram Society Tower A in Last Man in Tower, Aravind Adiga’s follow up to his Booker Prize winning debut novel, The White Tiger. . . . In his earlier works Adiga’s tender attention to the frustrations, yearning and anger of a cycle-cart puller, train station porter, and chauffeur lifted away the dehumanizing mask of vocation and poverty to reveal familiar vulnerabilities and aspirations. Now Adiga’s shrewd empathy extends to middle-class characters like the building’s secretary, and African born ‘nothing-man,’ who plans to use his windfall to move somewhere with a view of migrating flamingos. . . . Adiga examines cruelty and ugliness to find the trampled shreds of virtue and humanity beneath. His brilliance comes from showing good and bad hopelessly mixed together like, ‘water, the colour of Assam tea, on which floated rubbish and blazing light.’ After all—and in spite of our collective penchant for optimism—the same rubbish is piling up everywhere and there may not be much more we can do than appreciate the blazing light.”

—Erin Gilbert, The Rumpus.net

“Adiga, author of the highly acclaimed White Tiger, returns with this morality tale about events at a respectable, solidly middle-class building in Mumbai. The veneer of respectability and hard-earned bonhomie falls away after the residents—Hindu, Christian, and Muslim—are offered a windfall by an unscrupulous real estate developer who wants them to move. It is a credit to the author that the reader manages to keep...

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurKnopf

- Date d'édition2011

- ISBN 10 0307594092

- ISBN 13 9780307594099

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages400

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,72

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Last Man in Tower

Description du livre Etat : New. Well packaged and promptly shipped from California. Partnered with Friends of the Library since 2010. N° de réf. du vendeur 1LAUHV002K86

Last Man in Tower

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0307594092

Last Man in Tower

Description du livre Etat : New. Book is in NEW condition. N° de réf. du vendeur 0307594092-2-1

Last Man in Tower

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0307594092

Last Man in Tower

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0307594092

Last Man in Tower

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover0307594092

Last Man in Tower

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : Brand New. 400 pages. 9.50x6.50x1.50 inches. In Stock. N° de réf. du vendeur 0307594092