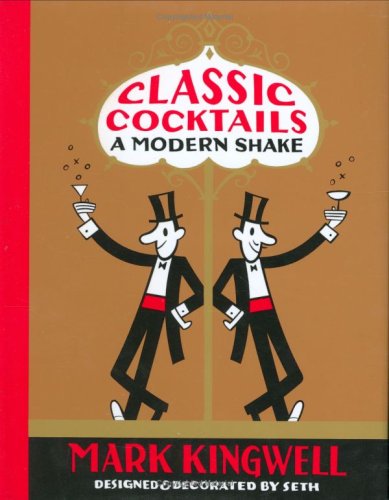

Articles liés à Classic Cocktails: A Modern Shake

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNBook by Kingwell Mark

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Extrait :

The Theory and Practice of Drink, in Five Parts

“My dear, this is a fashionable London parish, so called,” said Randolph. He carved the saddle of mutton savagely, as if he were rending his parishioners. “What hope is there for them this Lent? I suppose they can give up drinking cocktails.”

— Barbara Pym, An Unsuitable Attachment (1982)

A few years ago Conan O’Brien, the former television host and comedy producer, was asked to give a Class Day speech at Harvard University, his alma mater. He was a hit. Among other things, he described the lifelong burden of having attended the famous Ivy League finishing school in Cambridge, Mass. “You see,” O’Brien told the long rows of smiling grads, “you’re in for a lifetime of ‘and you went to Harvard?’ Accidentally give the wrong amount of change in a transaction and it’s, ‘and you went to Harvard?’ Ask the guy at the hardware store how these jumper cables work and hear, ‘and you went to Harvard?’ Forget just once that your underwear goes inside your pants and it’s ‘and you went to Harvard?’ Get your head stuck in your niece’s dollhouse because you wanted to see what it was like to be a giant and it’s ‘Uncle Conan, and you went to Harvard!?’”

Now, I didn’t go to Harvard myself. I went to Yale, where nobody expects anything of you except the occasional presidency. Still, I think I understand what O’Brien was telling the happy one-percenters as they got set to venture out into the world beyond the high-percentile security fence. I may not have gone to Harvard, but I am a philosopher.

For reasons that remain unclear, people outside the academic walls balk at the label “philosopher” in a manner not applied to “historian,” “political scientist,” or “physicist.” At the same time, curiously, everyone from defensive coordinators and garage mechanics to graphic designers and cooks speaks regularly about their “philosophy” of this or that: the nickel defence, fuel injection systems, white space, fusion spicing. As a result of this curious combination of normative escalation and commonplace lowering, mere philosophers — by which I just mean those of us whose lucky profession it is to teach the great traditions of human inquiry — are caught in a weird judgmental vertigo. We are not supposed to admit interests that fail some notional standard of intellectual seriousness; instead we are supposed to behave as if (in the great Vulcan inversion) we were dead from the neck down. Nobody knows who commands this standard, or why, but its dicta are clear.

Admit you watch kung fu movies or The Simpsons and it’s, “and you’re a philosopher?” Let slip your interest in college football or nascar and it’s, “and you’re a philosopher?” Confess a casual liking for suede sneakers or Cary Grant’s suits and it’s, “and you’re a philosopher?” Cocktails? A fatal lack of seriousness. This sort of judgment is distinct from those standard expressions of wonderment that a philosopher cannot change a tire, put up drywall, or find coordinates on a map. Whereas unworldliness confirms philosophical status, but only negatively, as a joke, worldliness disconfirms it as “serious.” Gotcha, and double gotcha!

Some people, obviously, have an interest in the subject of cocktails. For most of us, it is hardly an overpowering or obsessional calling. This interest is not merely theoretical, in that we like drinking drinks as well as writing about them. It is likewise not theoretical in another sense, because, despite the title of this introduction, we do not have, nor do we believe there to be, some Big Theory of cocktails. There is no philosophy of mixology.

One could of course subject cocktails to moral or sociological analysis, or both. One could, for example, place them in the same frame of “taste” and “production of consumption” as analyzed by Thorstein Veblen in his classic study The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899). The gentleman of leisure, Veblen says, “becomes a connoisseur in creditable viands of various degrees of merit, in manly beverages and trinkets, in seemly apparel and architecture, in weapons, games, dances, and narcotics. This cultivation of the aesthetic faculty requires time and application, and the demands made upon the gentleman in this direction therefore tend to change his life of leisure into a more or less arduous application to the business of learning how to live a life of ostensible leisure in a becoming way.”

This book does not take “manly beverages” seriously in that sense, and does not have much time for people who do. Such seriousness is, among other things, boring. The relevant other things include self-defeating, and tautological: first leisure becomes work, and then all judgments are reduced to claims of status. Note also the meta-irony first remarked by the late John Kenneth Galbraith, that only the scholarly, which is to say those who enjoy either private or state-sponsored leisure, have time to read Veblen! We will not bother to argue here the obvious truth that all scales of value have their own fatal self-contradictory blind spots, usually just about exactly where their holder is standing. Baseball games, no; art openings, yes. A cufflink collection, bad; a power tool collection, good. Video games, nasty; foreign films, uplifting. Every puritan is a dandy of his own convictions — and, of course, vice versa.

For what it’s worth, philosophers have long had an abiding interest in drink, if not always as served shaken and strained into a chilled glass. For anthropological and historical reasons, they tend to prefer wine. Everyone knows that Plato’s most appealing dialogue, Symposium, is a record of a drinking party where the vinous talk turned to love. Alcibiades, who comes late and drunk to the party, notes that one of Socrates’ many virtues is that he can drink anybody under the table. This famous capacity is just one reason Socrates has got under the Athenian golden boy’s skin.

Drink and other mood-altering substances have figured in many other corners of the tradition. Thomas Aquinas enjoyed his wine and his food with such unbridled gusto that a special table had to be fashioned for him, with an arc carved out to accommodate his ample paunch. Immanuel Kant, despite his reputation for deadly seriousness and strict insistence on moral duty, was a dedicated dandy and dinner-party bon vivant for most of his life. David Hume, who warned against the dangers of self-medication when in the throes of skeptical vertigo, nevertheless enjoyed a healthy and bibulous social life. His broad red Scottish face got redder still, we are told, when he was deep in his cups.

Biographie de l'auteur :

“My dear, this is a fashionable London parish, so called,” said Randolph. He carved the saddle of mutton savagely, as if he were rending his parishioners. “What hope is there for them this Lent? I suppose they can give up drinking cocktails.”

— Barbara Pym, An Unsuitable Attachment (1982)

A few years ago Conan O’Brien, the former television host and comedy producer, was asked to give a Class Day speech at Harvard University, his alma mater. He was a hit. Among other things, he described the lifelong burden of having attended the famous Ivy League finishing school in Cambridge, Mass. “You see,” O’Brien told the long rows of smiling grads, “you’re in for a lifetime of ‘and you went to Harvard?’ Accidentally give the wrong amount of change in a transaction and it’s, ‘and you went to Harvard?’ Ask the guy at the hardware store how these jumper cables work and hear, ‘and you went to Harvard?’ Forget just once that your underwear goes inside your pants and it’s ‘and you went to Harvard?’ Get your head stuck in your niece’s dollhouse because you wanted to see what it was like to be a giant and it’s ‘Uncle Conan, and you went to Harvard!?’”

Now, I didn’t go to Harvard myself. I went to Yale, where nobody expects anything of you except the occasional presidency. Still, I think I understand what O’Brien was telling the happy one-percenters as they got set to venture out into the world beyond the high-percentile security fence. I may not have gone to Harvard, but I am a philosopher.

For reasons that remain unclear, people outside the academic walls balk at the label “philosopher” in a manner not applied to “historian,” “political scientist,” or “physicist.” At the same time, curiously, everyone from defensive coordinators and garage mechanics to graphic designers and cooks speaks regularly about their “philosophy” of this or that: the nickel defence, fuel injection systems, white space, fusion spicing. As a result of this curious combination of normative escalation and commonplace lowering, mere philosophers — by which I just mean those of us whose lucky profession it is to teach the great traditions of human inquiry — are caught in a weird judgmental vertigo. We are not supposed to admit interests that fail some notional standard of intellectual seriousness; instead we are supposed to behave as if (in the great Vulcan inversion) we were dead from the neck down. Nobody knows who commands this standard, or why, but its dicta are clear.

Admit you watch kung fu movies or The Simpsons and it’s, “and you’re a philosopher?” Let slip your interest in college football or nascar and it’s, “and you’re a philosopher?” Confess a casual liking for suede sneakers or Cary Grant’s suits and it’s, “and you’re a philosopher?” Cocktails? A fatal lack of seriousness. This sort of judgment is distinct from those standard expressions of wonderment that a philosopher cannot change a tire, put up drywall, or find coordinates on a map. Whereas unworldliness confirms philosophical status, but only negatively, as a joke, worldliness disconfirms it as “serious.” Gotcha, and double gotcha!

Some people, obviously, have an interest in the subject of cocktails. For most of us, it is hardly an overpowering or obsessional calling. This interest is not merely theoretical, in that we like drinking drinks as well as writing about them. It is likewise not theoretical in another sense, because, despite the title of this introduction, we do not have, nor do we believe there to be, some Big Theory of cocktails. There is no philosophy of mixology.

One could of course subject cocktails to moral or sociological analysis, or both. One could, for example, place them in the same frame of “taste” and “production of consumption” as analyzed by Thorstein Veblen in his classic study The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899). The gentleman of leisure, Veblen says, “becomes a connoisseur in creditable viands of various degrees of merit, in manly beverages and trinkets, in seemly apparel and architecture, in weapons, games, dances, and narcotics. This cultivation of the aesthetic faculty requires time and application, and the demands made upon the gentleman in this direction therefore tend to change his life of leisure into a more or less arduous application to the business of learning how to live a life of ostensible leisure in a becoming way.”

This book does not take “manly beverages” seriously in that sense, and does not have much time for people who do. Such seriousness is, among other things, boring. The relevant other things include self-defeating, and tautological: first leisure becomes work, and then all judgments are reduced to claims of status. Note also the meta-irony first remarked by the late John Kenneth Galbraith, that only the scholarly, which is to say those who enjoy either private or state-sponsored leisure, have time to read Veblen! We will not bother to argue here the obvious truth that all scales of value have their own fatal self-contradictory blind spots, usually just about exactly where their holder is standing. Baseball games, no; art openings, yes. A cufflink collection, bad; a power tool collection, good. Video games, nasty; foreign films, uplifting. Every puritan is a dandy of his own convictions — and, of course, vice versa.

For what it’s worth, philosophers have long had an abiding interest in drink, if not always as served shaken and strained into a chilled glass. For anthropological and historical reasons, they tend to prefer wine. Everyone knows that Plato’s most appealing dialogue, Symposium, is a record of a drinking party where the vinous talk turned to love. Alcibiades, who comes late and drunk to the party, notes that one of Socrates’ many virtues is that he can drink anybody under the table. This famous capacity is just one reason Socrates has got under the Athenian golden boy’s skin.

Drink and other mood-altering substances have figured in many other corners of the tradition. Thomas Aquinas enjoyed his wine and his food with such unbridled gusto that a special table had to be fashioned for him, with an arc carved out to accommodate his ample paunch. Immanuel Kant, despite his reputation for deadly seriousness and strict insistence on moral duty, was a dedicated dandy and dinner-party bon vivant for most of his life. David Hume, who warned against the dangers of self-medication when in the throes of skeptical vertigo, nevertheless enjoyed a healthy and bibulous social life. His broad red Scottish face got redder still, we are told, when he was deep in his cups.

Philosopher and critic Mark Kingwell is the author of nine previous books, including the national bestsellers Better Living (1998) and The World We Want (2000). Currently a professor of philosophy at the University of Toronto, his scholarly work has appeared in many leading journals, including the Journal of Philosophy, Political Theory, and the Harvard Design Magazine. He is also a contributing editor of Harper’s Magazine and a regular contributor to Adbusters, the National Post, and the Globe and Mail. He has won many awards for his writing, including the National Magazine Award for both essays (2002) and columns (2004). Classic Cocktails is based on his award-winning cocktail column, which appears in the men’s magazine Toro.

Seth was born in 1962 in a rural Ontario town. Seth lives in Guelph, Ontario, with five cats, a gigantic collection of vintage records, comic books, and twentieth-century Canadiana, and his very patient wife. He regularly contributes illustrations to The New Yorker and the National Post. Seth’s comic-book series, Palookaville, has been collected into It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken and Clyde Fans. He is the designer of the bestselling The Complete Peanuts.

Seth was born in 1962 in a rural Ontario town. Seth lives in Guelph, Ontario, with five cats, a gigantic collection of vintage records, comic books, and twentieth-century Canadiana, and his very patient wife. He regularly contributes illustrations to The New Yorker and the National Post. Seth’s comic-book series, Palookaville, has been collected into It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken and Clyde Fans. He is the designer of the bestselling The Complete Peanuts.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurThomas Dunne Books

- Date d'édition2007

- ISBN 10 0312375239

- ISBN 13 9780312375232

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages228

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 16,52

Frais de port :

EUR 4,13

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Classic Cocktails: A Modern Shake

Edité par

Thomas Dunne Books

(2007)

ISBN 10 : 0312375239

ISBN 13 : 9780312375232

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 2212140050

Acheter neuf

EUR 16,52

Autre devise