Articles liés à December

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNSaturday

Wilson’s got his arm deep in the twisted mess of wires, pipes, and tubing that festers there beneath his truck’s dented hood like the intestines of some living thing. He gropes at the undersides of things, trying to find whatever leaking crack it is that’s caused him now to fail inspection twice. That and the broken hinge of the driver’s seat, which he keeps upright by stacking milk crates behind it.

“Damn truck,” he mutters. “Goddamn.” He says it though he loves this truck, he wouldn’t ever trade it in. It keeps him busy on the weekends; it’s a project, a chore.

Today is Wilson’s birthday. He looks younger than his forty-two years, and in many ways he feels it. He feels the same as he always has, all his life, same as he did as a kid stalking through the woods with a BB gun or a young man drunk at a keg party, and so sometimes he doesn’t recognize the city businessman he’s become, with a weekend house in the country, a wife, a child who breaks his heart. He’d always thought by the time he got to somewhere around forty-two he’d be ready to accept stiffening joints and graying hair, wrinkles and cholesterol pills, but when these things apply to him he feels as if there’s been some mistake; he’s not quite ready for them yet.

He pulls his arm out from under the truck’s hood and starts to wipe the grease from his hand onto the rag he’s taken from the bag of them in the hall closet: old clothing ripped into neat squares. He stares absently at the truck’s engine as he rubs the rag over his fingers one by one, then he shuts the hood. He’ll have to take the thing in to the shop, he thinks; he’s no mechanic. A breeze chills him, and he looks at the sky. The clouds are low and rolling. Fall leaves ride the air, and he imagines gulls at the nearby shore coasting the wind. Late autumn always fills him with something like fear, or dread, or sadness; he’s never sure how to label the feeling. It’s an awareness of the inevitable impending dark, barren cold of winter, which when it comes is fine, he knows, and eventually ends. Still, he shudders.

Firewood, he thinks. He should chop some firewood. He’s bought a new rack to store it on outside this winter, with a tarp attached to keep it dry; he assembled it last weekend, and now it needs filling. He should bring some wood inside, too; it’s getting cold enough for a fire, and Isabelle loves a fire. She’ll sit in front of one for hours, reading, or drawing, or staring at the flames, rotating her body when one side gets too hot. Like a chicken on a spit, he once said, which made her laugh.

He walks to the garage for an ax. He tosses the dirty rag he’s holding into the trash can, which is nearly overflowing with cardboard, Styrofoam, wood scraps, newspapers, empty paint cans and oil bottles, and other rags like this one. He stares at the newest rag and tilts his head in recognition. The rag is flannel, printed with purple alligators. It’s from a nightgown he brought back years ago for Isabelle, from a business trip to where? Spain, or maybe Portugal that time; he can’t remember. But he does remember buying it, calling Ruth back in the States to make sure that he bought the right size, and the right size slippers to match.

He takes the rag from the trash can and holds it in his hand. He considers folding it up, tucking it away somewhere, but then he sees no point in that. He hesitates a second more, then tosses it back into the can, lifts his ax, and goes outside.

...

Ruth stands over the kitchen sink peeling carrots. “I thought I’d make split pea,” she says. “A huge vat of it that we can keep frozen and warm up, you know, on those Friday nights when we get here and it’s late and cold and the furnace is out or the pipes are frozen. I feel like that happens more and more each winter, but wouldn’t it be nice to have a warm bowl of soup? That and a fire, if your father ever gets around to chopping wood.” She puts the last peeled carrot down onto the pile of them stacked on the cutting board and watches the skin spin down the drain as she runs the disposal.

“You know,” she says, chopping the carrots into coins, “your uncle called this morning. He’s convinced he’s under surveillance. He’s being buzzed by black helicopters. He’s counted thirty-six since yesterday.” She wipes the hair from her forehead with the back of her wrist. “And,” she says, “he thinks Ronna’s mind is being poisoned.” Ruth looks up. “Because she uses aspartame, not sugar.” She pushes the carrot coins to the side of the cutting board and reaches for an onion.

The kitchen opens onto the family room, the rooms themselves separated only by the wide counter where Ruth stands. She looks up over the counter and into the other room, where her daughter sits at the table, her head bent low over her sketchbook, a pencil clutched firmly in her hand. She looks stern with concentration, and Ruth can tell by the whiteness of her fingertips that she is pressing the pencil hard against the page. She is framed by the picture window, and her silhouette is dark against the sky behind her, its steely canvas broken only by the jagged limbs of the apple tree, Ruth’s favorite. Bare long before the other trees this fall, the apple tree is dying, Ruth knows. Wilson wanted to cut it down, but she wouldn’t let him.

“It’s dead, Ruth,” he’d said.

“It’s not dead,” she’d said. “It’s dying. Let’s just let it die.”

The winter will kill it, she suspects. It’s meant to be a bad one.

“Do you know what my mother said to me on her deathbed?” Ruth asks, flaking the onion’s skin away. “I asked her, I said, ‘Mother, what am I going to do about Jimmy?’ And she looked at me, and she smiled, and she said, ‘Ruthie, I don’t know, but he is your problem now.’ And, my God, words have never been truer.” She picks the knife back up and holds it above the onion, then she pauses. “I’m just not quite sure what I’m supposed to do.” She lowers the knife onto the onion. “What do I say about thirty-six black helicopters, for instance? Do I say I see them, too? That everyone does? Or do I tell him he’s delusional?”

Ruth steps back from the onion to dry her eyes. Isabelle has not looked up. A large pot of water on the stove has finally come to a boil, and Ruth pours several bags of split peas in. “There,” she says. “That should last us for a couple months at least. Maybe even all winter. Though I’d like to make lentil, too, at some point.” She turns back to the cutting board. Her daughter hunches over her sketchbook, very still except for the slow and deliberate movements of her drawing hand.

“I’d like to see what you’re drawing, Isabelle,” Ruth says. “When you’re finished, if you want to show me.”

Her daughter says nothing, though Ruth didn’t expect an answer. Isabelle hasn’t spoken for nine months now. She has been to countless doctors and psychiatrists, but nothing seems to help, to penetrate the silence. Ruth is sure that she is somehow responsible. There are images that haunt and tease: Isabelle at two, sitting alone on the edge of the sandbox in the same blue overalls every day, watching as the other children play; Isabelle at four, sitting small among her preschool classmates, glancing often at Ruth with her book in the corner to make sure she hasn’t left her there alone; Isabelle in tears on her first day of kindergarten when finally Ruth arrived to pick her up, ten minutes late. Isabelle had taken literally her teacher’s joking threat to turn the stragglers into chicken soup, and she had nightmares for months. Of all days, on that day, Ruth should have been on time. And maybe she shouldn’t have stayed with her daughter at preschool, the only parent, until April, when Isabelle was finally ready to let her go. Maybe she should have gotten into the sandbox with her daughter and helped her to make friends instead of allowing her to sit as a spectator until she was comfortable. She’s read countless books on parenting, trying to figure out just where she went wrong, and how she can make it right. Each book tells her something different: she should discipline, she should tolerate, she should encourage independence, she should allow for dependence—and each book points to a mistake. Where she should have tolerated, she disciplined instead; where she should have disciplined, she didn’t.

She lifts the cutting knife and begins to chop the second onion. She hears the back door whine open and waits to hear it close; it doesn’t. “Shut the door!” she yells. “You’re letting out the heat!”

Wilson appears in the kitchen door with a bundle of firewood in his arms. “What are you making?” he asks.

“Split pea. Could you please close the door behind you when you come inside?”

“My arms are full. And I’m going right back out,” he says, passing through the kitchen into the family room. “I’m going to bring another load in.”

“Yes, well, in the meantime I can already feel the draft.”

Ruth sets her knife down and goes to shut the door herself. When she comes back into the kitchen, she sees Wilson crouched at the hearth, building a fire. “It’s fire season, Belle,” he’s saying. “I thought you might like a fire. Doesn’t that sound good?”

Isabelle doesn’t look up from her drawing. Ruth watches as Wilson balls up newspaper to set beneath the logs. “Don’t forget to open ...

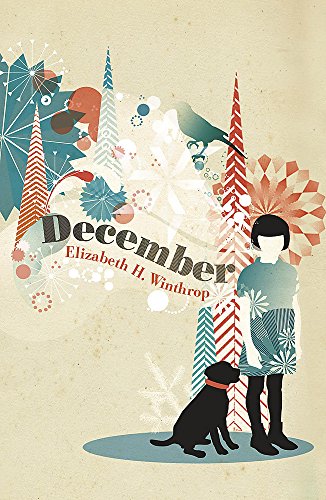

Eleven-year-old Isabelle hasn't spoken in nine months, and as December begins the situation is getting desperate. Her mother has stopped work to devote herself full-time to her daughter's care. Four psychiatrists have already given up on her, and her school, which until now has allowed her to study from home, will not take her back in the New Year. Her parents are frantically trying to understand what has happened to their child so they can help her, but they cannot escape the thought of darker possibilities. What if Isabelle is damaged beyond their reach? Will she never speak again? Is it their fault?

As her parents spiral around Isabelle's impenetrable silence, she herself emerges, in a fascinating portrait of an exceptional child, as a bright young girl in need of help yet too terrified to ask for it.

By the talented young author of FIREWORKS, this is a novel of spellbinding emotional power about a family in crisis, showing the delicate web of threads that connect a husband and wife, parents and children, and how easily it can tear.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurSceptre

- Date d'édition2008

- ISBN 10 0340961422

- ISBN 13 9780340961421

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages256

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

December

Description du livre Etat : New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition 0.97. N° de réf. du vendeur bk0340961422xvz189zvxnew