Articles liés à Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-America...

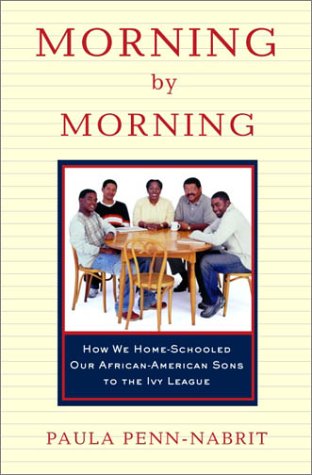

Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League - Couverture rigide

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

“OH, JESUS! . . .

WHAT HAPPENED?”

I wish I could say we began home schooling because we knew it was the best thing for our sons. I wish I could say we took our time, examined our options, and came to the calm and rational decision that home schooling was the preferred educational experience for them. Regrettably, I honestly cannot say those things. We did not begin home schooling because we thought it was the best thing for our sons. We did not take our time and examine our options. We did not reach the calm and rational decision that home schooling was the preferred educational experience for them. Most embarrassing of all, our entry into home schooling was brought about by external factors—something happened, something terrible and traumatic. As much as we work at being free and conscious people of color, independent actors rather than reactors, the truth is we began home schooling as a reaction to something some white people did to us.

When we moved from Jacksonville, Florida, to the Columbus, Ohio, area in 1989, we enrolled our sons in the local country day school for boys. I was elated! It was the school affiliated with the all-girl country day school I had attended as a young girl. The grounds were expansive, with stately brick buildings atop gently rolling hills that gave way to several perfectly framed playing fields. It offered academic programming from pre-K through twelfth grade in three manageable divisions—Lower School, Middle School, and Upper School—with imaginative after-school programs as well. I expelled a huge sigh of relief when we enrolled the boys; I thought there would be no further educational choices to deal with until they were ready to apply to college! As I followed the impressive line of expensive SUVs, vans, and luxury sedans up the long and winding drive, the idyllic scene created an atmosphere of renewed optimism for me every morning. I comforted myself with the belief that an environment so aesthetically appealing had to be good for our sons. And surely, no institution attentive to the soil requirements of each tree, shrub, and rhododendron could be insensitive to the needs of a child—any child. Plus, the school was horrendously expensive, at least by Columbus, Ohio, standards, and like many middle-class parents, we thought anything that costly had to be good. Overall, C. Madison and I felt comfortable with the school, and felt certain our family would be a welcomed and contributing addition to the community. After our combined twelve years in prep school, Wellesley and Dartmouth, everything about the place was familiar: the facilities, the administration, the faculty, the students, and their parents. We recognized this population: there were moderate Democrats and compassionate conservatives, and, of course, a lot of Anglophiles; it was a gentle combination of Protestant Gentiles (mostly Episcopalian and Presbyterian), a few Catholics, a smattering of Reform Jews, and a tiny representation of Buddhist, Islamic, and Hindu families. Many students were the children or nephews of kids with whom my sisters and I had gone to prep school. It was the kind of school where mothers wore jumpers and coordinated turtlenecks with little designs on them, and a mom or a dad could show up for a parent/teacher conference in a cotton crewneck sweater, cords, and boat shoes with no socks, without an eyebrow being raised. There was a definite L.L. Bean look to the place.

It felt like a very “white” place to us; and, in that sense, it didn’t feel negatively alien or strange, just different yet familiar. We had absolutely no doubt about the wisdom of enrolling our boys there. We knew it wasn’t perfect. We didn’t expect it to be perfect. We were making a conscious trade-off: cultural relevance in exchange for academic competitiveness.

During our brief, two-year tenure there, the boys did well. They were well liked, well behaved, and well adjusted. We got along with most of the faculty and the other parents. I sincerely enjoyed my engagements with the other “Mommys”; and although we had different variations on it, our theme issues were the same. We each wanted the best for our sons. We had lots of informal get-togethers and play dates, and the boys’ friends and classmates were always welcome at our home.

At the boys’ school, I was “Head Homeroom Mother,” served on countless and hideously time-consuming committees (book fairs, antiques shows, and patron parties), and was an assistant den mother of Evan’s Cub Scout den. School turned out to be a part-time job for me. Because there were so few black children, and no black faculty or administrators, we felt we needed to be visible for our sons’ benefit and for the benefit of the rest of the academic community.

When I was in prep school, I was the only black student in my class. There were no black teachers or administrative staff. The only black adults were the folks on the kitchen and janitorial staff; they were wonderfully supportive and never missed an opportunity to tell me how proud they were of me and how confident they were of my success. But even with the support of my parents at home and the black workers at school, I definitely felt the sense of isolation of being different and somewhat set apart. Often, such physical isolation leads to psychological isolation, alienation, and fragmentation. The absence of black adults and the accompanying isolation of African-American children in predominantly white schools can be unhealthy. Creating the impression that academically talented black children are an anomaly is unhealthy for everybody because it supports the myth of the exceptional Negro. This is the person who looks black, but isn’t really like “them.” The myth contributes to self-loathing and a desire to disassociate from other black people.

Initially, we were well aware of the challenges facing black kids in white schools, but we were convinced we could make the situation at prep school work for our children. Overall, the private school experience was good. The facilities were excellent, the faculty was good, and the environment seemed adequate. What was our chief complaint? We wanted the school to live up to its commitment to diversity within the community.

The school said it was unable to find any African-American adults, much less male adults, who were qualified to teach at such an outstanding educational institution. The school asked for the help and assistance of the black parents in finding and recruiting such rare and elusive individuals. While I didn’t say it, I felt the school was making the issue of black faculty solely the responsibility of the black parents, and I felt this was inappropriate. But I tried to be cooperative. The school had a diversity committee that met in the evenings, ostensibly so parents could attend and participate. The group met for months to discuss the issue facing us, namely, how to find black faculty without lowering the standards of the school. After all, none of us wanted that, did we? What would be the point of our sons’ attendance if the school’s reputation was tarnished? The unstated and racist assumption here was that it would take some kind of Herculean effort to find any black people, much less black men, who could match the qualifications of the current faculty and administration. In fact, while the faculty and administration were certainly appropriately educated for secondary school employment, there was hardly an abundance of spectacular credentials, e.g., Oxford or Ivy League–level PhDs. Primarily, this was an institution run by state and land grant college graduates. It was hard for me to believe that it was really that difficult to find black people at the same schools. I tried to find nice, nonthreatening ways to say this, ways that were not so provocative that people couldn’t hear me. I really tried to be a team player.

At about the same time the diversity committee was meeting, the school decided to become coeducational and hired an older, wealthy, white woman as the diversity coordinator. She was extremely well educated and seemed quite sincere in her commitment to coeducation and diversity. During our evening meetings, several black parents expressed concerns about coeducation and its potential impact on our sons; specifically, C. Madison and I felt that adding girls to the mix was a complication the school was not prepared to handle. The concerns the black parents had about our sons were not adequately addressed in a single-sex environment. Many of us were convinced that adding girls, most of whom would be the sisters of the majority population, would further diminish the school’s attention to the issues of race and multiculturalism. We were also concerned about the whole issue of sexual tension in a newly coeducational environment where unexamined and unresolved issues of racism were present. I was having a very difficult time expressing these concerns in a way that could be heard.

Thinking the intersecting issues of race and gender were too complicated to grasp in an evening after dinner, I scheduled a daytime appointment with the diversity coordinator. I expressed my commitment to gender equity, because as Sojourner Truth allegedly asked once, “Ain’t I a woman?” But I tried to explain that I was as concerned about how the school saw the balance between issues of race and gender. The diversity coordinator listened atten- tively and then explained that the issues of gender were more important because people can, with enough money, escape the challenge of racial diversity, thereby making it an elective, while the issue of gender is inescapable, thereby making it mandatory. While I thought the analysis was grossly oversimplified and I vehemently disagreed with it, I felt enlightened by our conversation. As a black woman with black sons, I knew the school would place the needs of white girls ahead of those of black boys. The diversity coordinator knew that too; it’s just that that wasn’t really a problem for her.

We talked to each other, and that was good—it was progress, it was a beginning—but it was insufficient. We were, as they say, “close, but no dog biscuit.” I was beginning to see the school’s limitations in dealing with the issue. I was beginning to see that what we wanted—change—was at cross-purposes with what the school wanted—modification. The school year ended where it had begun, with lots of dialogue but no black faculty.

In conversations with other black parents over the summer, I thought we should begin the new academic year with a more focused and collective approach. Previously, we each had addressed our concerns individually, even though many of those concerns were collective. We knew they were connected and collective issues because we were all pretty much dealing with the same themes, just with different variations. We discussed these themes with each other to get ideas on strategies and approaches, and sometimes to just vent. This was, as they say, all good, except that the school didn’t have a framework for addressing these issues. I thought the school didn’t have a framework because it didn’t understand that these were, in fact, connected and collective issues within the institution. Because we, as black parents, had consistently addressed our concerns about our sons individually, the school saw the concerns as individual, isolated “incidents,” not institutionalized issues worthy of its collective attention. I thought our individual approaches possibly had made it more difficult for the school to see the breadth of the issues. I thought we would all be better served if we could identify and articulate which of our individual issues and concerns were actually collective concerns within the institution. I thought we needed a gathering, and a picnic seemed perfect.

So I decided to organize an unofficial back-to-school picnic for the school’s black families. I went through the school directory and created a listing of all the black families, and sent each one a postcard invitation. It was a basic, run-of-the-mill, prep-school-type postcard invitation: heavy, white card stock; hunter green borders with navy blue print (handwritten, of course). It was neither militant nor threatening; there were no kente cloth insignias and no red, black, and green maps of “Afrika.” A new school year had begun; it was late September, the weather was still great, and the picnic was a chance for some black families to connect. We didn’t live in the same neighborhoods and we didn’t belong to the same private clubs, but we did share a common desire to provide the best possible education for our sons with the least amount of psychological damage.

At the picnic, I passed out copies of the invitation list with addresses and phone numbers. We talked about the importance of increasing our visibility in the school. I encouraged more of the mothers to consider becoming room mothers. We talked about the importance of increased financial support of the school, beyond the astronomical tuition. We talked about encouraging black teachers, administrators, and graduate students interested in teaching to apply to the school. We talked about the impact the older boys could have on the younger ones, and how to increase their interaction. (C. Madison and I had used a couple of the older black guys at the school as baby-sitters for our sons, and it had been great. It created another link at the school for our sons, another connection, another opportunity to learn the traditions and unwritten rules that form the bonds that help make a private school education so special.) While there were only a few boys in each grade, there was no reason they couldn’t support one another outside the artificial boundaries of grade. Further, there was no reason why we as parents couldn’t network and help create a more supportive environment for all our sons.

We all ate; the boys played; and we talked and discussed our concerns from about two in the afternoon until almost eight that night. By the end of the evening, lots of new connections had been formed and old ones were strengthened. We had a great time; the parents felt energized; and the kids were knocked out. I went to bed feeling like we were well on our way to addressing the issues of race and diversity at school constructively and collectively.

The very next week, I was called into the headmaster’s office. He was clutching one of my invitations, and he was furious! He could not believe I had had the “audacity” to host such an event without the school’s knowledge or his permission. It had never occurred to me ask permission to host a social gathering. After all, this was a picnic, not a coup. I explained to him that this was a social gathering and no more sinister than the countless cocktail parties he had probably attended over the summer with various families from school. He was unable to see the analogy. Further, he was outraged on behalf of some black parents who had been insulted by their inclusion on the invitation list. I sincerely and actively listened both for information and for understanding. Apparently, the insulted black parents felt this was a return to segregation and the headmaster agreed. I asked him if he had been as outraged at any of the segregated events he had attended at private clubs over the summer. Again, he claimed not to see the analogy, an unbelievable allegation for someone so highly educated. In any event, he felt I owed him and the school an apology. I disagreed.

The meeting ended and I went to pick up the boys in the never-ending carpool line. The headmaster and I had had serious disagreements before, so I was not concerned about this latest incident. I was confident of the health of our family’s relationship with him and with the school; but, as it turned out, I was very wrong. The...

But ultimately, Paula and C. Madison felt that they knew what was best for their sons. So in 1991—when Evan was nine and twins Charles and Damon were eleven—the children were withdrawn from the exclusive country day school they’d been attending.

In Morning by Morning, Paula Penn-Nabrit discusses her family’s emotional transition to home schooling and shares the nuts and bolts of the boys’ educational experience. She explains how she and her husband developed a curriculum, provided adequate exposure to the arts as well as quiet time for reflection and meditation, initiated quality opportunities for volunteerism, and sought out athletic activities for their sons. At the end of each chapter, she offers advice on how readers can incorporate some of the steps her family took—even if they aren’t able to home-school; plus, there’s a website resource guide at the end of the book.

Charles and Damon were eventually admitted to Princeton, and Evan attended Amherst College. But Morning by Morning is frank about the challenges the boys faced in their transition from home schooling to the college experience, and Penn-Nabrit reflects on some things she might have done differently.

With great warmth and perception, Paula Penn-Nabrit discusses her personal experience and the amazing outcome of her home-schooling experience: three spiritually and intellectually well balanced sons who attended some of the top educational institutions in this country.

What we learned from home schooling:

-Use your time wisely.

-Education is more than academics.

-The idea of parent as teacher doesn’t have to end at kindergarten.

-The family is our introduction to community.

-Extended family is a safety net.

-Yes, kids really do better in environments designed for them.

-Travel is an education.

-Athletics is more than competitive sports.

-Get used to diversity.

-It’s okay if your kids get angry at you—they’ll get over it!

-from Morning by Morning

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurVillard Books

- Date d'édition2003

- ISBN 10 0375507744

- ISBN 13 9780375507748

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Nombre de pages304

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. 1st Edition. Book. N° de réf. du vendeur ABE-1670438032950

Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0375507744

Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Buy for Great customer experience. N° de réf. du vendeur GoldenDragon0375507744

Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League

Description du livre Etat : New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition 1.16. N° de réf. du vendeur bk0375507744xvz189zvxnew

Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Brand New Copy. N° de réf. du vendeur BBB_new0375507744

Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0375507744

Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover0375507744

Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League Penn-Nabrit, Paula

Description du livre hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur MESLF-09116-08-22-2022

Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : Brand New. 1st edition. 304 pages. 9.50x6.50x1.25 inches. In Stock. N° de réf. du vendeur 0375507744

Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League

Description du livre Etat : New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 1.16. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-0375507744-new