Articles liés à The View from the Summit

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Tenzing called it the roar of a thousand tigers. hour after hour it came whining and screeching in an unrelenting stream from the west with such ferocity it set the canvas of our small Pyramid tent cracking like a rifle range. We were 25,800 feet up on the South Col, a desolate saddle between the upper slopes of Everest and Lhotse. Rather than easing off, the gale grew more violent the longer it went on. I began to fear that our heaving and thrashing shelter must surely be wrenched from its mooring, leaving us exposed and unprotected amongst the ice and boulders. I was braced between Tenzing Norgay and the tent wall with no room to stretch out to my full length. Jammed in tight, just turning over was difficult and resulted in a spasm of panting. The thudding canvas beat constantly against my ribs and whenever my head touched the fabric my brain felt like it had been placed under a pneumatic drill. As a weight-saving device, we had left behind our inner sleeping bags and this was proving to be a considerable mistake. Even wearing all my down clothing I found the icy breath from outside penetrating through to my bones. A terrible sense of fear and loneliness dominated my thoughts. What is the sense in it all? I asked myself. A man was a fool to put up with this! When it came, sleep was a half-world of noise and cold. Then my air mattress deflated, freezing my hip where it rested on the ice. It was the worst night I have ever spent on a mountain.

On the other side of Tenzing my old climbing friend and fellow New Zealander George Lowe and the English climber Alf Gregory were similarly hunched up in their sleeping bags, twisting about in futile search for some position less uncomfortable and for some escape from the bitter cold. We were using the oxygen sleeping sets at the rate of one liter per minute, which made it easier to doze. At this height you dribble a good bit in your sleep, and when your oxygen bottle gives out you wake with a terrible start and your rubber mask is all clammy and frigid. Throughout the endless night I kept looking at my watch, wondering if it had broken, for the hands hardly seemed to move. Finally, when the hour hand crawled around to 4 A.M., I struck a match and read the thermometer on the tent wall. It was -25°C and still pitch black. I gently nudged Tenzing and he was immediately awake and, in his universally helpful fashion, wriggled up and began lighting our primus stove. The tent started warming up a little and I retreated callously deeper into my bag and thought about the events of the previous day. What a momentous day it had been!

The 26th May 1953 had dawned cold, bright and clear. We were at Camp VII, 24,000 feet up in the middle of the Lhotse Face. Overhead a cloud of powder snow was being blown off Everest's upper ramparts, but it didn't look too bad. It boded well for the first assault pair of Charles Evans and Tom Bourdillon. They were at Camp VIII on the South Col and would be going all out for the South Summit this day. Their start would need to be better than ours. At Camp VII it took us ages to get moving. Even simple tasks at this height take an inordinate length of time, as oxygen-starved brains and bodies have little concentration and lack coordination. At 8:45 A.M., after breakfasting on biscuits and lukewarm tea, Tenzing and I, the second assault pair, led off on one rope. Our support team of George Lowe and Alf Gregory followed on a second rope. Behind them were our three high-altitude Sherpas who would help us establish Camp IX on the South-East Ridge. Bringing up the rear were five load-carrying Sherpas who were taking supplies only as far as the South Col. Charles Evans and Tom Bourdillon had been chosen for the first assault because they had developed a successful partnership and were better versed than any of us in using the more experimental closed-circuit oxygen equipment which, if it worked, would allow faster and more economical progress toward the South Summit and, maybe, beyond. If the weather made it a one-dash venture, they were equipped to take their chance. Meanwhile Tenzing and I had established our credentials by being acclimatized and strong, so we would be close behind, awaiting our turn, with the cumbersome but more familiar open-circuit systems.

We crossed a frighteningly unstable crevasse and made our way up the long steep slope of the Lhotse Face. We hadn't gone far before the ever-observant George shouted and pointed up to the distant South-East Ridge, where we could see two tiny figures making their way upward toward the South Summit. It could only be the first assault party of Evans and Bourdillon. Their main objective was to reach the South Summit itself but they could make the decision to carry on toward the top if they thought they could do it. Further down the South-East Ridge we could see another couple and judged this to be John Hunt and Da Namgyal carrying some assault supplies for us as high as they could on the ridge. It was an exciting scene -- we were really on the move!

Tenzing and I rushed on ahead and reached the top of the Geneva Spur. We caught glimpses of the first assault team making excellent time up the ridge until they disappeared into the cloud covering the upper part of the mountain. I noticed that Tenzing looked decidedly subdued. We dropped down the 200-foot descent to make our second visit to the South Col. The first had been when we had pioneered the major lift of supplies to the col which had made the attempts on the summit possible. The small group of tents in the camp, bucking in the wind, looked very lonely indeed and we crawled inside one for shelter.

I kept looking out the door and very soon picked up two figures moving down the Great Couloir, and traveling very slowly. I hurried across the South Col to meet them. It was John Hunt and Da Namgyal and they were completely exhausted. They had carried their loads until they could carry no longer and then dumped their supplies on the South-East Ridge. John had left his half bottle of oxygen there too and had come down without it, so was in a desperate condition. I supported him across the col as best I could but he collapsed time and time again. It was only when I obtained some oxygen from the camp and returned with it to John that his energy partly returned and he made it back to his tent and crawled thankfully inside.

By now George and his team had joined us, and he suddenly gave a yell. Through a break in the clouds his sharp eyes had caught a view of the tiny figures of Evans and Bourdillon, still above 27,000 feet, but descending into the Great Couloir. Clouds swept in again and then lifted barely ten minutes later. To our astonishment we realized that our two friends were now at the bottom of the couloir. Obviously they had slipped and fallen hundreds of feet. Only the soft snow at the bottom had saved them from plummeting into a crevasse or down the terrible Kangshung Face. They, too, were completely exhausted, only able to move a few steps before stopping and slumping over. George and I hurried across to join them. They were an astonishing sight -- covered in ice from head to foot. It demanded a great effort to get them over to a tent and push them inside with John Hunt.

With numb lips they told their story. Right from the start they had problems with their powerful but experimental closed-circuit oxygen equipment. When all went well they made excellent speed. High on the South-East Ridge Charles Evans' problems increased and they reached the South Summit with faulty gear and feeling very tired. The weather, too, had deteriorated with cloud and wind. The very stubborn Tom Bourdillon wanted to carry on, whatever the risks, but Charles Evans was sure that if they persisted they would never return. "If you do that, Tom," warned Charles Evans, "you will never see Jennifer again." So they came down.

That was a terrible night on the South Col! Charles and Tom had performed magnificently and, despite technical problems, had achieved their objective of reaching the South Summit. Now I had learned why Tenzing had been so morose -- he thought Charles and Tom were about to reach the top of Everest. He desperately wanted a Sherpa to be in the first summit team and he was always confident that he himself was the right Sherpa for this task. I, too, had a slight sense of guilt. I greatly admired what Charles and Tom had done but I had a regrettable feeling of satisfaction as well. They hadn't got to the top -- there was still a job left for Tenzing and me to do. But the storm raged on and intensified, so it was already clear there was little chance of Tenzing and myself moving upward in the morning.

The day dawned in a fury of wind and drifting snow which after a few hours started to ease a little, although there was still streaming cloud over the upper mountain. Our main worry was the importance of getting Charles Evans and Tom Bourdillon down to safer levels. I talked to Charles about the final stretches of the mountain and, although he was never prone to exaggeration, he sadly told me that he didn't think we'd make it along the summit ridge. But I didn't take this too seriously -- I had the confidence to believe I was a more experienced snow and ice climber than Charles or Tom and I felt I was probably fitter than either of them. We would see when the time came.

Around midday they emerged slowly from their tent and were joined by Sherpa Ang Temba who had come up with us to carry high on the mountain, but he had been nauseated all night so had to go down, too. To save oxygen for us they generously decided to do without it on the descent. I watched with great concern as they weaved their way up the slope toward the top of the Geneva Spur, the obstacle blocking access to descent of the Lhotse Face. To my horror, I saw Tom crumple and fall flat on the snow. Riveted with disbelief, I watched him drag himself to his feet, take a few more tottering steps, and then crash to the snow again. Clearly, he would need oxygen to have any hopes of getting down the mountain. Charles came back down with me and we quickly prepared an oxygen set which I carried up to Tom who was now on his hands and knees. With the oxygen turned on full volume, he was able to get slowly to his feet and very tentatively move up the slope again.

I returned to the tents and, when I told John Hunt and George Lowe of my considerable worry about the others getting down safely, John agreed that someone must go with them. Somewhat laboriously, he explained his conviction that he regarded it as his duty, as expedition leader, to supervise the action from the South Col. If something went wrong he might be needed higher on the mountain. George would have to go down as escort. I was greatly taken aback by this suggestion, as I was expecting considerable help from George, but I also realized how desperately keen John was to stay on the South Col, despite his exhaustion. It was difficult to know how to react to this decision. George had no such qualms. In strong and even bitter terms he pointed out how much fitter he was than John and how important he was to the success of the expedition. John had burned himself out, he said, on his great carry up the South-East Ridge and would be useless in an emergency. All very true, but unpalatable words to hear just the same. John remained adamant -- George must go! I don't know why nobody mentioned Alf Gregory. He didn't seem to be around when these crises occurred. A disgruntled George started making his preparations for departure. However, it was only a few moments before John's sense of responsibility overruled his tired mind and he agreed that he himself was indeed the right person to take the party down.

I have never admired John more than I did at that moment. When we were alone, gray and drawn, but with his blue eyes frostier than ever, John gripped my arm and told me of his deep belief that we had a duty to climb the mountain. Many thousands of people had pinned their hope and faith on us and we couldn't let them down.

"The most important thing is for you chaps to come back safely. Remember that," he implored. "But get up if you can!"

I carried John's load for him to the top of the Geneva Spur and was distressed at how weak he was as he weaved from side to side. We arrived at the top of the slope only to see that Tom, despite breathing oxygen, had once again collapsed on the snow. It seemed that the whole expedition was falling to pieces. Noting my concern, Charles turned his warm and friendly smile on me and said consolingly, "Don't worry, Ed. I'll get them down."

John immediately decided he would take the back place on the rope and play the critical anchor role, but Charles merely did a middleman loop, handing it to his leader and said, "Get in there, John." Which he meekly did. With John in the middle position, they shuffled off. Watching them disappear from view down the steep and demanding Lhotse Face was a disheartening sight. George was with me and, to vent some of the guilt I felt at letting four exhausted men descend unaided, I turned on him and snapped unreasonably, "It will be all your fault, George, if they don't get down!"

George and I spent the rest of the day preparing the oxygen, food and equipment for the next day's assault, periodically ducking into our tents to warm ourselves. With the wind behind us, we crossed over the South Col and looked down the great East or Kangshung Face as no one had ever seen it from the top before, and a very awesome sight it proved to be. We turned back into the bitter wind and had a fearful struggle reaching our tents again, but were greatly encouraged at how fit we still felt and how freely we could work and move at 26,000 feet without oxygen. We were still worried about the descending party but we knew that with every hundred feet of height they lost, their strength would improve. As the day wore on, my thoughts turned increasingly to the next day ahead of us but I couldn't help dwelling at times on those rather awful moments with the departing team. Where were Tenzing and Alf Gregory, I asked myself, when we were making all our executive decisions, as I kindly described our rather ferocious arguments? Probably Tenzing was very wisely keeping his distance. And where was all the help when I was carrying loads and encouraging people up and down the demanding slope to the top of the Geneva Spur? I was pretty sure that Alf had been resting comfortably in his sleeping bag, conserving his strength for what he saw as the battles ahead. The altitude of 26,000 feet distorted everyone's judgment during this long and difficult day.

That night I moved with Tenzing into the relative comfort of a Meade tent. I had been wandering around all afternoon with a span-ner in my hand (George claimed I looked more like a mechanic than a mountaineer) but it meant I knew precisely how much oxygen we had and decided we could spare a tiny bit for sleeping. It was still blowing hard, but at first I slept quite well, although periodically I'd waken stiff and cold to find my air mattress had deflated due to ice in the valve. It reminded me of an earlier time I had been sleeping with Tenzing at much lower altitude and woke to see him on his hands and knees bowing and murmuring in a strange fashion. I accepted that he was carrying out some sophisticated Buddhist ceremony until I realized that he was only inflating a faulty air mattress.

Early in the morning I was woken by a sudden quietness and realized the wind had stopped. Although it soon returned, it was much more spasmodic and a good sign for the day ahead. We started making our slow preparations and at 7:30 A.M. I crossed to George and Alf in the Pyramid tent. We agreed to start and accepted that we would have to carry heavy loads. Two high-altitude porters were supp...

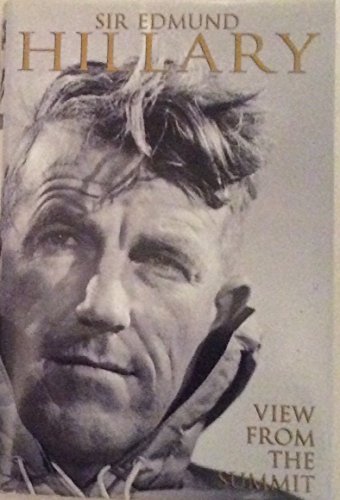

AN ORDINARY MAN WHO BECAME THE

CENTURY'S MOST IMPORTANT EXPLORER

Adventurers the world over have been inspired by the achievements of Sir Edmund Hillary, the first man ever to set foot on the summit of Mount Everest. In this candid, wry, and vastly entertaining autobiography, Hillary looks back on that 1953 landmark expedition, as well as his remarkable explorations in other exotic locales, from the South Pole to the Ganges. View From The Summit is the compelling life story of a New Zealand country boy who daydreamed of wild adventures; the pioneering climber who was knighted by Queen Elizabeth after scaling the world's tallest peak; and the elder statesman and unlikely diplomat whose groundbreaking program of aid to Nepal continues to this day, paying his debt of worldwide fame to the Himalayan region.

More than four decades after Hillary looked down from Everest's 29,000 feet, his impact is still felt -- in our fascination with the perils and triumphs of mountain climbing, and in today's phenomenon of extreme sports. The call to adventure is alive and real on every page of this gripping memoir.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurDoubleday

- Date d'édition1999

- ISBN 10 0385600208

- ISBN 13 9780385600200

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Nombre de pages320

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,97

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

View From the Summit

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0385600208

View From the Summit

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover0385600208

View From the Summit

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0385600208

VIEW FROM THE SUMMIT

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.63. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-0385600208

View From the Summit

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0385600208

View From the Summit Hillary, Sir Edmund

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur DRN1---0166