Articles liés à The Perfect Nazi: Discovering My Grandfather's...

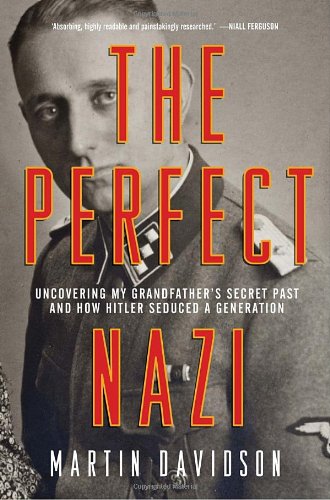

The Perfect Nazi: Discovering My Grandfather's Secret Past and How Hitler Seduced a Generation - Couverture rigide

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNThe Perfect Nazi In 1926, at the age of twenty, a trainee dentist called Bruno Langbehn joined the Nazi party. Growing up in a Germany that was impoverished and humiliated by the defeat of the First World War, Bruno was one of the first young men to sign up. This title traces Bruno's journey from disillusioned adolescent to SS Officer to mysterious grandfather. Full description

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Extrait :

1. Funeral in Berlin

Edinburgh and Berlin 1960–1984

It’s such a sweet picture. That’s me, chuckling away, my podgy little arms waving about in delight. Behind lies the gentle curve of a Scottish beach an hour’s drive east of Edinburgh, where I was born and grew up. It’s sunny and warm; the perfect day for a drive to the shore, armed with a brand new super-8 cine-camera. Holding me to his shoulder is a man in his mid-fifties, smiling, only too happy to play his part in this little family moment. In fact, he is my German grandfather and he seems very proud of his first grandson. He has a distinctive face, with its close-cropped hair, large ears, bulbous nose, stern eye-line and slightly serrated smile. Beyond that, he appears perfectly benign, a little severe maybe, but open-faced, and unembarrassed to have his cheek pawed by a gurgly baby. It’s August 1961, and I am nine months old.

For the next thirty years, like anyone who has at least one German parent, I was taught to remember that there was so much more to Germany than just the Nazis. The world’s obsession with Hitler, and with the Second World War, was just a vast distraction from the rest of German history. Even though it was a struggle to get terribly excited about the court of Frederick the Great, or the premiership of Willi Brandt, I did my bit and tried hard to avoid simply collapsing the entire meaning of the word Germany into a synonym for the Third Reich. And then, in 1992, I realized I had no choice.

Bruno Langbehn, my grandfather, the man in the cine footage, had died at the age of eighty-five. Only in the weeks after his death did I discover that ‘Papa’, as my mother always called him, hadn’t just been a German dentist who had happened to live through the tumultuous decades of the Nazi nightmare. Nothing of the sort, in fact.

I had always had my suspicions, of course, and as the years went past I had chipped away at the protective carapace that had been erected around his early career. I had tried to prise information out of my mother, but it was only with him dead that my mother felt able, finally, to tell me the truth – or at least one tiny bit of it.

I had never met my other, Scottish, grandfather. I knew he had been marched off to the trenches of the First World War with the Seaforth Highlanders and, against the odds, had managed to survive, unlike many of his friends, or indeed his older brother. Returning from France, he had decided what he most wanted to do with his life was to fish for salmon and drive down his golf handicap, each and every day. To do so he needed a job that didn’t take him away from his rods and his mashie niblicks, so he opened a cinema in his highland hometown of Dingwall, in Ross-shire. He never needed to work during daylight hours again. My father grew up in its shadow, collecting the posters, loitering in the projector room, in his wartime Cinema Mac-Paradiso. But all that standing up to his thighs in ice-cold Highland water did for my Davidson grandfather, and he died many years before I was even born. I would never know more about him than what my father could tell me. I had no idea even what he looked like, how he spoke, no sense at all of his personality beyond family anecdote.

The relationship my sister, Vanessa, and I had with Bruno, however, was more complex, and more immediate. Our lives did overlap, and we grew up with a very clear impression of what kind of man we thought he was. To this day I can call to mind his appearance, a sense of his personality and presence. And yet despite my vivid recollections of him, much about Bruno remained unknown. The mystery didn’t arise from simple distance, and the inevitable haziness of memory. The obscurity that enveloped him always felt deliberately constructed, a smokescreen and not just generational amnesia.

It wasn’t hard to see why this might be so. Simply knowing where and when he was born – Prussia, 1906 – had ominous significance. It was impossible for him not to have come to adulthood in the heart of Nazi darkness. And, as for all Germans of his generation, it raised a mass of implied questions. What had he done? What had he been? What did he know? Bruno’s behaviour did nothing to dispel such questions; on the contrary, it positively invited them. Of all my German relatives, he was the least apologetic, the least self-effacing. Even in his seventies he bristled with views about life, about politics and human nature, about the follies of the world, which he expressed with uncompromising force, and the vigour of someone whose whole life had been one long argument. In this regard he always struck me as being the most explicitly belligerent German, the one whose convictions about the present most provoked you into daring to think about his past.

But thinking about it was as far as we were ever allowed to get. Talking about it – or even asking questions about it – was not encouraged in our home. My mother would refuse point blank to be drawn into our speculations, deflecting and evading them whenever they surfaced. We were children, indulging in subjects we couldn’t possibly understand. The subject was closed. The result was that we grew up with huge and tantalizing gaps in our knowledge of him. These only made him more mysterious, as did the defensiveness with which my other relatives had encircled him. He was a no-go area.

If, as a child, I hadn’t been curious about my older German relatives, everyone else around me certainly was. The culture of Britain in the 1960s and 70s was dominated by the long shadow of the Second World War, which had ended only fifteen years before my birth. Like the rest of my generation, I may not have known much about their historical reality, but the ‘Nazis’ were as vivid to me as the Daleks on Dr Who. I thought I knew what they looked like, what they sounded like, how they behaved. Defeating them had been the greatest achievement of the twentieth century.

They were tall and blond; they often had scars; they clicked their heels and held their cigarettes with sadistic precision. They didn’t talk, they barked, though sometimes they issued their threats in quiet, determined tones, choosing their every word carefully, and with cruel, menacing deliberation. More usually they shouted, especially when enraged, which they seemed always to be, at which point they would scream into phones, or bring their fist crashing down on desks. They were oleaginous in their behaviour towards attractive women, who would recoil and squirm when their hands were kissed. I knew all this because not a week went by without some kind of war film on television, whose basic grammar got replicated wildly in comics and playground games. I watched them all avidly, as did everyone my age. We all loved imagining what it must have been like to have been a Spitfire pilot, a jungle commando or a cocoa-supping officer on the bridge of an Atlantic destroyer. I may have been half-German, but I wasn’t the slightest bit confused about who the heroes were. Every Messerschmitt shot down, every German battleship sunk, every defeated Wehrmacht soldier was a triumph to cheer. Above all Nazis were them, separated from us (not just the British, but the entire human race) by an uncrossable divide. And yet I still stopped short of seeing my grandfather reflected in these depictions.

There was no question that my German relatives, especially my grandfather, had been on the wrong side, and yet even as a child I couldn’t fully equate him with the grimly robotic ‘Krauts’ and ‘squareheads’ whose walk-on parts were so unvarying – there to display the arrogance and cruelty that would be tamed by Tommy bravado. He would have had to have been unutterably evil to have been one of them. Surely the truth was less melodramatic than that. The movies appeared to bear me out. As I grew older, a new generation of Second World War Germans were depicted in a much less one-dimensionally unpalatable way. They had stopped being either morons or psychopaths and had become, instead, conflicted officers usually alienated from, and deeply disillusioned by, the Nazi regime. Most ambiguous of all was Das Boot, which featured in the character of the captain played by Jurgen Prochnow, the ultimate example of a man with no love for the politics that had triggered the war, anxious only to do his duty and get his men out alive. Perhaps that was what my grandfather had been like? Needless to say, my mother felt much more comfortable with these more complex and ambiguous portraits of Germans at war. So it appeared possible to wear a German uniform without necessarily being a fanatical Nazi.

But as a twelve-year-old, I felt residual self-consciousness about having a German mother. It still chafed a little. Talking to the parents of school friends, my heart would always beat a little faster when explaining how Berlin was our favourite holiday destination. Nobody ever said anything, but I knew what they were thinking. Of course, far less inhibited were my school friends. For them it was all too obvious. They would taunt me with their playground Sieg Heils, giggling as they decided my mysterious German relatives must all have been Nazi soldiers who knew Hitler personally. It was embarrassing, though I don’t recall finding any of this especially traumatic. I was big, I was good at sports, and therefore not a natural public-school victim. Anyway, it wasn’t as if I had an overtly German name. But they only had to come and visit our house to see with their own eyes that I wasn’t, finally, 100 per cent British. Anyone meeting my mother could see, and hear, in an instant, that she was German.

She had come to Edinburgh in 1958, to learn English, had met my Scottish father, g...

Revue de presse :

Edinburgh and Berlin 1960–1984

It’s such a sweet picture. That’s me, chuckling away, my podgy little arms waving about in delight. Behind lies the gentle curve of a Scottish beach an hour’s drive east of Edinburgh, where I was born and grew up. It’s sunny and warm; the perfect day for a drive to the shore, armed with a brand new super-8 cine-camera. Holding me to his shoulder is a man in his mid-fifties, smiling, only too happy to play his part in this little family moment. In fact, he is my German grandfather and he seems very proud of his first grandson. He has a distinctive face, with its close-cropped hair, large ears, bulbous nose, stern eye-line and slightly serrated smile. Beyond that, he appears perfectly benign, a little severe maybe, but open-faced, and unembarrassed to have his cheek pawed by a gurgly baby. It’s August 1961, and I am nine months old.

For the next thirty years, like anyone who has at least one German parent, I was taught to remember that there was so much more to Germany than just the Nazis. The world’s obsession with Hitler, and with the Second World War, was just a vast distraction from the rest of German history. Even though it was a struggle to get terribly excited about the court of Frederick the Great, or the premiership of Willi Brandt, I did my bit and tried hard to avoid simply collapsing the entire meaning of the word Germany into a synonym for the Third Reich. And then, in 1992, I realized I had no choice.

Bruno Langbehn, my grandfather, the man in the cine footage, had died at the age of eighty-five. Only in the weeks after his death did I discover that ‘Papa’, as my mother always called him, hadn’t just been a German dentist who had happened to live through the tumultuous decades of the Nazi nightmare. Nothing of the sort, in fact.

I had always had my suspicions, of course, and as the years went past I had chipped away at the protective carapace that had been erected around his early career. I had tried to prise information out of my mother, but it was only with him dead that my mother felt able, finally, to tell me the truth – or at least one tiny bit of it.

I had never met my other, Scottish, grandfather. I knew he had been marched off to the trenches of the First World War with the Seaforth Highlanders and, against the odds, had managed to survive, unlike many of his friends, or indeed his older brother. Returning from France, he had decided what he most wanted to do with his life was to fish for salmon and drive down his golf handicap, each and every day. To do so he needed a job that didn’t take him away from his rods and his mashie niblicks, so he opened a cinema in his highland hometown of Dingwall, in Ross-shire. He never needed to work during daylight hours again. My father grew up in its shadow, collecting the posters, loitering in the projector room, in his wartime Cinema Mac-Paradiso. But all that standing up to his thighs in ice-cold Highland water did for my Davidson grandfather, and he died many years before I was even born. I would never know more about him than what my father could tell me. I had no idea even what he looked like, how he spoke, no sense at all of his personality beyond family anecdote.

The relationship my sister, Vanessa, and I had with Bruno, however, was more complex, and more immediate. Our lives did overlap, and we grew up with a very clear impression of what kind of man we thought he was. To this day I can call to mind his appearance, a sense of his personality and presence. And yet despite my vivid recollections of him, much about Bruno remained unknown. The mystery didn’t arise from simple distance, and the inevitable haziness of memory. The obscurity that enveloped him always felt deliberately constructed, a smokescreen and not just generational amnesia.

It wasn’t hard to see why this might be so. Simply knowing where and when he was born – Prussia, 1906 – had ominous significance. It was impossible for him not to have come to adulthood in the heart of Nazi darkness. And, as for all Germans of his generation, it raised a mass of implied questions. What had he done? What had he been? What did he know? Bruno’s behaviour did nothing to dispel such questions; on the contrary, it positively invited them. Of all my German relatives, he was the least apologetic, the least self-effacing. Even in his seventies he bristled with views about life, about politics and human nature, about the follies of the world, which he expressed with uncompromising force, and the vigour of someone whose whole life had been one long argument. In this regard he always struck me as being the most explicitly belligerent German, the one whose convictions about the present most provoked you into daring to think about his past.

But thinking about it was as far as we were ever allowed to get. Talking about it – or even asking questions about it – was not encouraged in our home. My mother would refuse point blank to be drawn into our speculations, deflecting and evading them whenever they surfaced. We were children, indulging in subjects we couldn’t possibly understand. The subject was closed. The result was that we grew up with huge and tantalizing gaps in our knowledge of him. These only made him more mysterious, as did the defensiveness with which my other relatives had encircled him. He was a no-go area.

If, as a child, I hadn’t been curious about my older German relatives, everyone else around me certainly was. The culture of Britain in the 1960s and 70s was dominated by the long shadow of the Second World War, which had ended only fifteen years before my birth. Like the rest of my generation, I may not have known much about their historical reality, but the ‘Nazis’ were as vivid to me as the Daleks on Dr Who. I thought I knew what they looked like, what they sounded like, how they behaved. Defeating them had been the greatest achievement of the twentieth century.

They were tall and blond; they often had scars; they clicked their heels and held their cigarettes with sadistic precision. They didn’t talk, they barked, though sometimes they issued their threats in quiet, determined tones, choosing their every word carefully, and with cruel, menacing deliberation. More usually they shouted, especially when enraged, which they seemed always to be, at which point they would scream into phones, or bring their fist crashing down on desks. They were oleaginous in their behaviour towards attractive women, who would recoil and squirm when their hands were kissed. I knew all this because not a week went by without some kind of war film on television, whose basic grammar got replicated wildly in comics and playground games. I watched them all avidly, as did everyone my age. We all loved imagining what it must have been like to have been a Spitfire pilot, a jungle commando or a cocoa-supping officer on the bridge of an Atlantic destroyer. I may have been half-German, but I wasn’t the slightest bit confused about who the heroes were. Every Messerschmitt shot down, every German battleship sunk, every defeated Wehrmacht soldier was a triumph to cheer. Above all Nazis were them, separated from us (not just the British, but the entire human race) by an uncrossable divide. And yet I still stopped short of seeing my grandfather reflected in these depictions.

There was no question that my German relatives, especially my grandfather, had been on the wrong side, and yet even as a child I couldn’t fully equate him with the grimly robotic ‘Krauts’ and ‘squareheads’ whose walk-on parts were so unvarying – there to display the arrogance and cruelty that would be tamed by Tommy bravado. He would have had to have been unutterably evil to have been one of them. Surely the truth was less melodramatic than that. The movies appeared to bear me out. As I grew older, a new generation of Second World War Germans were depicted in a much less one-dimensionally unpalatable way. They had stopped being either morons or psychopaths and had become, instead, conflicted officers usually alienated from, and deeply disillusioned by, the Nazi regime. Most ambiguous of all was Das Boot, which featured in the character of the captain played by Jurgen Prochnow, the ultimate example of a man with no love for the politics that had triggered the war, anxious only to do his duty and get his men out alive. Perhaps that was what my grandfather had been like? Needless to say, my mother felt much more comfortable with these more complex and ambiguous portraits of Germans at war. So it appeared possible to wear a German uniform without necessarily being a fanatical Nazi.

But as a twelve-year-old, I felt residual self-consciousness about having a German mother. It still chafed a little. Talking to the parents of school friends, my heart would always beat a little faster when explaining how Berlin was our favourite holiday destination. Nobody ever said anything, but I knew what they were thinking. Of course, far less inhibited were my school friends. For them it was all too obvious. They would taunt me with their playground Sieg Heils, giggling as they decided my mysterious German relatives must all have been Nazi soldiers who knew Hitler personally. It was embarrassing, though I don’t recall finding any of this especially traumatic. I was big, I was good at sports, and therefore not a natural public-school victim. Anyway, it wasn’t as if I had an overtly German name. But they only had to come and visit our house to see with their own eyes that I wasn’t, finally, 100 per cent British. Anyone meeting my mother could see, and hear, in an instant, that she was German.

She had come to Edinburgh in 1958, to learn English, had met my Scottish father, g...

"A fascinating and extraordinary journey into the heart of Nazism."

— Ben Macintyre, Author Of Agent Zigzag And Operation Mincemeat

"Martin Davidson has done a brave thing: he has confronted and revealed his own family's Nazi past. The result is absorbing, highly readable and painstakingly researched."

— Niall Ferguson

"The utterly compelling account of what it's like to discover that your grandfather was a ruthless officer in Hitler's SS."

— Philip Kerr

"The Perfect Nazi is a terrific piece of writing, shedding light on how ordinary Germans abetted the Nazi terror and how in later years all was conveniently "forgotten"."

— David Cesarani, Author Of Eichmann: His Life And Crimes

"A fascinating and compelling account. This is an important book for anyone interested in the moral climate which led to the Holocaust and the other crimes of the Third Reich."

— Adrian Weale Evening Standard (UK)

"A riveting narrative that brings a fresh vividness to a familiar episode."

— Valerie Grove The Times (UK)

"Davidson's journey into his grandfather's past makes for a compelling and unsettling tale ... A thoughtful and affecting book."

— Telegraph (UK)

"Shocking and compelling ... Hollywood fiction turns out to be not so far from the truth as revealed in Martin Davidson's fascinating account of his maternal grandfather."

— Sunday Times (UK)

"Chillingly addictive ... Davidson was right to decide that, whatever the cost, Bruno had "forfeited the right" to post-humous anonymity."

— Roger Hutchinson Scotsman (UK)

"This highly readable, thought-provoking book highlights the challenges that German families have faced as they seek to put the past behind them ... It offers a window on how the different generations grappled with the Nazi past."

— Hester Vaizey Independent (UK)

— Ben Macintyre, Author Of Agent Zigzag And Operation Mincemeat

"Martin Davidson has done a brave thing: he has confronted and revealed his own family's Nazi past. The result is absorbing, highly readable and painstakingly researched."

— Niall Ferguson

"The utterly compelling account of what it's like to discover that your grandfather was a ruthless officer in Hitler's SS."

— Philip Kerr

"The Perfect Nazi is a terrific piece of writing, shedding light on how ordinary Germans abetted the Nazi terror and how in later years all was conveniently "forgotten"."

— David Cesarani, Author Of Eichmann: His Life And Crimes

"A fascinating and compelling account. This is an important book for anyone interested in the moral climate which led to the Holocaust and the other crimes of the Third Reich."

— Adrian Weale Evening Standard (UK)

"A riveting narrative that brings a fresh vividness to a familiar episode."

— Valerie Grove The Times (UK)

"Davidson's journey into his grandfather's past makes for a compelling and unsettling tale ... A thoughtful and affecting book."

— Telegraph (UK)

"Shocking and compelling ... Hollywood fiction turns out to be not so far from the truth as revealed in Martin Davidson's fascinating account of his maternal grandfather."

— Sunday Times (UK)

"Chillingly addictive ... Davidson was right to decide that, whatever the cost, Bruno had "forfeited the right" to post-humous anonymity."

— Roger Hutchinson Scotsman (UK)

"This highly readable, thought-provoking book highlights the challenges that German families have faced as they seek to put the past behind them ... It offers a window on how the different generations grappled with the Nazi past."

— Hester Vaizey Independent (UK)

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurVIKING

- Date d'édition2010

- ISBN 10 0385662343

- ISBN 13 9780385662345

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 74,36

Frais de port :

EUR 21,56

De Canada vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

The Perfect Nazi: Discovering My Grandfather's Secret Past and How Hitler Seduced a Generation Davidson, Martin

Edité par

Doubleday Canada

(2010)

ISBN 10 : 0385662343

ISBN 13 : 9780385662345

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur XA3--0063

Acheter neuf

EUR 74,36

Autre devise