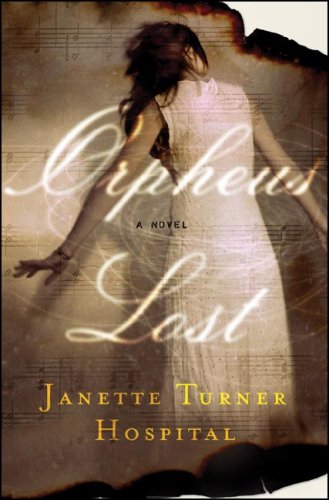

Articles liés à Orpheus Lost

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNBook by Hospital Janette Turner

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Extrait :

Afterwards, Leela realized, everything could have been predicted from the beginning. Every clue was there, the ending inevitable and curled up inside the first encounter like a tree inside a seed. The trouble was that the interpretation was obvious only in retrospect.

Fact one: Mishka Bartok was an insoluble equation.

Fact two: Leela could never leave insoluble equations alone. Before Mishka, she believed that every code could be broken and codes which had yet to be deciphered were an irresistible provocation. They kept her awake at night.

She did sense from the start that Mishka was a question without an answer, but she could not accept this. Neither could she prove it. Not then. The riddle of Mishka was like Fermat’s last theorem for which no solution exists. In 1630, Fermat himself could prove that all the way to infinity no solution would ever exist, but he kept his proof to himself and it hovered like marsh fire in algebraic and numerical dreams. It lured mathematicians for three centuries, almost for four. It drove them mad. Computations were exchanged between Oxford and Rome, between Berlin, Bologna, the Sorbonne, until finally, late in the twentieth century, someone at Princeton caught the proof of non-provability in his net. “I was ten years old,” the Princeton genius said–Andrew Wiles was his name–“when I first read about Fermat. It looked so simple, his theorem, yet all the mathematicians in history couldn’t solve it. From that moment, I knew I’d never let it go.”

Obsession, wrote a seventeenth-century don who gave his life to the quest, is its own heaven and its own hell.

The words struck Leela like a blow. She copied them onto an index card which she thumb-tacked to the wall above her desk.

Sometimes, in dreams, when the beginning began again, Mishka would warn her: “Don’t follow me, Leela.” He would lift the violin to his chin and begin to play. He would turn his back and walk away from her, walk down into the subway tunnels, deeper and deeper, the bow rising above his left shoulder and falling again, the notes drifting back, plaintive and irresistible. “Leave me alone,” he would say. “Don’t follow me.”

“Where are you going?” Leela would call, but he never answered.

Leela would push against the fog of underground air, her eyes fixed on the pale flash of bowstrings until the dark swallowed them. “Mishka! Wait!” she would call. “Wait for me!”

That always made him pause. “Don’t call me Mishka.” His sadness would speak in a minor key, two sweeps of the bow. “That’s not my name anymore.” He would wheel back then, briefly, to face her and she would see with dread–in dream after recurring dream–that indeed he was no longer Mishka, but a skeletal idea of himself thinly draped in a shroud. Some ghastly internal aura shone from the sockets that were his eyes. Humerus, radius and ulna, the bones of the arm, kept moving his bow across the strings. “Don’t follow me, Leela,” his skeleton warned.

The tunnel smelled of monstrous decay, but even so, even knowing within the dream that she should turn and flee back up into sunlight, Leela would be powerless. Mishka’s music drugged her. Waking or sleeping, she could close her eyes and see him as she saw him that first time: not just the visual memory lurking entire, but the sounds, the sensations, the hurly-burly of Harvard Square, the slightly dank odor of the steps as she descended into the underworld of the Red Line, the click of tokens and turnstiles, the gust of fragrance from the flower sellers, the funky sweat of the homeless, the subdued roar of the trains, and then those haunting notes....

She stood riveted, her token poised above the slot in the turnstile. She had heard two bars, perhaps three, in the brief lull between trains.

“Would you mind?” said someone behind her.

“What? Oh... sorry.” She let the token fall through the slot. She pushed against the steel bar and into the space of the music. There was another pause between trains, a few bars, a stringed instrument, clearly, but also a tenor voice. Was it a cello that the singer was playing? Surely not. No street musician would cart such a large and unwieldy instrument down into the bowels of the city, onto the trains, among the crowds; but the sound seemed too soft for a violin, too husky, too throaty. She could feel the music graphing itself against her skin, her body calculating the frequencies and intervals of the whole subway symphony: base throb of trains, tenor voice, soft lament of the strings, a pleasing ratio of vibrations. Mathematical perfection made her weak at the knees.

She was letting the music reel her in, following the thread of it, leaning into the perfect fifths. Crowds intruded, echoes teased her, tunnels bounced the sound off their walls–now the music seemed to be just ahead, now to the right–and two minutes in every five, the low thunder of the trains muffled all. The notes were faint, they were clear, they were gone, they were clear again: unbearably mournful and sweet. Leela was not the only one affected. People paused in the act of buying tokens. They looked up from newspapers. They turned their heads and scanned the walls and ceiling of the subway cavern for speakers. With one foot on the outbound train, a man was arrested by a phrase and stepped back out of the sliding doors.

“Where is that gorgeous sound coming from?” he asked Leela. “Is it a recording?”

“A street musician,” she said. “Someone playing an early instrument, I think, a Renaissance violin, or something like that.”

“Over there,” the man pointed.

“Must be. Yes.”

“Extraordinary,” the man said. He began to run.

Leela followed him the length of the inbound platform to where a dense knot of commuters huddled. For a while the music was clearer as they approached, and then it was not, and then it seemed to be behind them again. Leela turned, disoriented. Her hands were shaking. The man who had stepped back from the outbound train leaned against a pillar with his eyes closed, rapt. Leela saw a woman surreptitiously wiping her sleeve across her eyes.

The violin itself was weeping music. Sometimes it wept alone; sometimes the tenor voice sorrowed along with it in a tongue not quite known but intuitively understood. The singer was singing of loss, that much was certain, and the sorrow was passing from body to body like a low electrical charge.

Leela recognized the melody, but although she could analyze the mathematical structure of any composition, she had trouble remembering titles of works and linking them to the right composers. It was an aria from some early opera, that much she knew. Gluck, probably. She had to hear all of it.

Ahead of her was an impenetrable cordon of backs.

Leela closed her eyes and pressed her hands to her face. She had a sense of floating underwater and the water was warm and moving fast and she was willing to be carried away by it. It was this way back in childhood in summer ponds in South Carolina, or on the jasmine-clotted Hamilton house veranda, or in deep grass, or lying under the pines with local boys; it was this way in later carnal adventures: body as fluid as soul. Everything was part of the euphoric storm surge which swept Leela up and rushed her toward something radiant that was just out of reach.

A fist of air punched her in the small of her back and a tidal wave of announcements drowned the music. Her hair streamed straight out in front of her face like a pennant. Words rumbled like thunder. Stopping all stations to shshshshs clang clang for Green Line change at Park clang shshshshsh.... Bucking and pushing ahead of the in-rush of train, a hard balloon of air plowed through the knot of listeners and scattered them.

That was when Leela caught her first glimpse of Mishka Bartok.

His head was bent over his instrument, his eyes focused on his fingered chords and his bow. He was oblivious to the arrival of the train. His body merged with the music and swayed. He was slender and pale, his dark hair unruly. A small shock of curls fell down over his left eye. When he leaned into the dominant notes, the curls fell across the sounding board of the instrument and he tossed them back with a flick of his head. Leela thought of a racehorse. She thought of a faun. Incongruously, she also thought of a boy she had known in childhood, a boy named Cobb, a curious boy with a curious name, a boy who had been possessed of the same skittish intensity which somehow let you know that, if cornered, this was a creature who would not yield. The violin player had Cobb’s fierce and haunted eyes.

There was no hat on the platform in front of him, no box, no can, no open violin case for donations, and the absence of any such receptacle seemed to bother the listeners. Someone tucked a folded bill into the side pocket of the violin player’s jeans but he appeared not to notice. A student in torn denim shorts took off his cloth hat and placed it beside the closed violin case as tribute and people threw coins and placed dollar bills–ones, fives, tens even–in the hat but the musician seemed indifferent and unaware. Some listeners boarded the inbound train, some seemed incapable of moving. Leela let five trains come and go, bracing herself each time against the buffeting of air. She had now worked her way forward to the innermost circle. She was four feet from the man with the violin. She could feel the intensity of his body like a series of small seismic waves against her own.

Trains arrived and departed, some people left but more gathered, the crowd around the man with the violin kept getting larger. His instrumental repertoire seemed inexhaustible–he barely paused betwe...

Présentation de l'éditeur :

Fact one: Mishka Bartok was an insoluble equation.

Fact two: Leela could never leave insoluble equations alone. Before Mishka, she believed that every code could be broken and codes which had yet to be deciphered were an irresistible provocation. They kept her awake at night.

She did sense from the start that Mishka was a question without an answer, but she could not accept this. Neither could she prove it. Not then. The riddle of Mishka was like Fermat’s last theorem for which no solution exists. In 1630, Fermat himself could prove that all the way to infinity no solution would ever exist, but he kept his proof to himself and it hovered like marsh fire in algebraic and numerical dreams. It lured mathematicians for three centuries, almost for four. It drove them mad. Computations were exchanged between Oxford and Rome, between Berlin, Bologna, the Sorbonne, until finally, late in the twentieth century, someone at Princeton caught the proof of non-provability in his net. “I was ten years old,” the Princeton genius said–Andrew Wiles was his name–“when I first read about Fermat. It looked so simple, his theorem, yet all the mathematicians in history couldn’t solve it. From that moment, I knew I’d never let it go.”

Obsession, wrote a seventeenth-century don who gave his life to the quest, is its own heaven and its own hell.

The words struck Leela like a blow. She copied them onto an index card which she thumb-tacked to the wall above her desk.

Sometimes, in dreams, when the beginning began again, Mishka would warn her: “Don’t follow me, Leela.” He would lift the violin to his chin and begin to play. He would turn his back and walk away from her, walk down into the subway tunnels, deeper and deeper, the bow rising above his left shoulder and falling again, the notes drifting back, plaintive and irresistible. “Leave me alone,” he would say. “Don’t follow me.”

“Where are you going?” Leela would call, but he never answered.

Leela would push against the fog of underground air, her eyes fixed on the pale flash of bowstrings until the dark swallowed them. “Mishka! Wait!” she would call. “Wait for me!”

That always made him pause. “Don’t call me Mishka.” His sadness would speak in a minor key, two sweeps of the bow. “That’s not my name anymore.” He would wheel back then, briefly, to face her and she would see with dread–in dream after recurring dream–that indeed he was no longer Mishka, but a skeletal idea of himself thinly draped in a shroud. Some ghastly internal aura shone from the sockets that were his eyes. Humerus, radius and ulna, the bones of the arm, kept moving his bow across the strings. “Don’t follow me, Leela,” his skeleton warned.

The tunnel smelled of monstrous decay, but even so, even knowing within the dream that she should turn and flee back up into sunlight, Leela would be powerless. Mishka’s music drugged her. Waking or sleeping, she could close her eyes and see him as she saw him that first time: not just the visual memory lurking entire, but the sounds, the sensations, the hurly-burly of Harvard Square, the slightly dank odor of the steps as she descended into the underworld of the Red Line, the click of tokens and turnstiles, the gust of fragrance from the flower sellers, the funky sweat of the homeless, the subdued roar of the trains, and then those haunting notes....

She stood riveted, her token poised above the slot in the turnstile. She had heard two bars, perhaps three, in the brief lull between trains.

“Would you mind?” said someone behind her.

“What? Oh... sorry.” She let the token fall through the slot. She pushed against the steel bar and into the space of the music. There was another pause between trains, a few bars, a stringed instrument, clearly, but also a tenor voice. Was it a cello that the singer was playing? Surely not. No street musician would cart such a large and unwieldy instrument down into the bowels of the city, onto the trains, among the crowds; but the sound seemed too soft for a violin, too husky, too throaty. She could feel the music graphing itself against her skin, her body calculating the frequencies and intervals of the whole subway symphony: base throb of trains, tenor voice, soft lament of the strings, a pleasing ratio of vibrations. Mathematical perfection made her weak at the knees.

She was letting the music reel her in, following the thread of it, leaning into the perfect fifths. Crowds intruded, echoes teased her, tunnels bounced the sound off their walls–now the music seemed to be just ahead, now to the right–and two minutes in every five, the low thunder of the trains muffled all. The notes were faint, they were clear, they were gone, they were clear again: unbearably mournful and sweet. Leela was not the only one affected. People paused in the act of buying tokens. They looked up from newspapers. They turned their heads and scanned the walls and ceiling of the subway cavern for speakers. With one foot on the outbound train, a man was arrested by a phrase and stepped back out of the sliding doors.

“Where is that gorgeous sound coming from?” he asked Leela. “Is it a recording?”

“A street musician,” she said. “Someone playing an early instrument, I think, a Renaissance violin, or something like that.”

“Over there,” the man pointed.

“Must be. Yes.”

“Extraordinary,” the man said. He began to run.

Leela followed him the length of the inbound platform to where a dense knot of commuters huddled. For a while the music was clearer as they approached, and then it was not, and then it seemed to be behind them again. Leela turned, disoriented. Her hands were shaking. The man who had stepped back from the outbound train leaned against a pillar with his eyes closed, rapt. Leela saw a woman surreptitiously wiping her sleeve across her eyes.

The violin itself was weeping music. Sometimes it wept alone; sometimes the tenor voice sorrowed along with it in a tongue not quite known but intuitively understood. The singer was singing of loss, that much was certain, and the sorrow was passing from body to body like a low electrical charge.

Leela recognized the melody, but although she could analyze the mathematical structure of any composition, she had trouble remembering titles of works and linking them to the right composers. It was an aria from some early opera, that much she knew. Gluck, probably. She had to hear all of it.

Ahead of her was an impenetrable cordon of backs.

Leela closed her eyes and pressed her hands to her face. She had a sense of floating underwater and the water was warm and moving fast and she was willing to be carried away by it. It was this way back in childhood in summer ponds in South Carolina, or on the jasmine-clotted Hamilton house veranda, or in deep grass, or lying under the pines with local boys; it was this way in later carnal adventures: body as fluid as soul. Everything was part of the euphoric storm surge which swept Leela up and rushed her toward something radiant that was just out of reach.

A fist of air punched her in the small of her back and a tidal wave of announcements drowned the music. Her hair streamed straight out in front of her face like a pennant. Words rumbled like thunder. Stopping all stations to shshshshs clang clang for Green Line change at Park clang shshshshsh.... Bucking and pushing ahead of the in-rush of train, a hard balloon of air plowed through the knot of listeners and scattered them.

That was when Leela caught her first glimpse of Mishka Bartok.

His head was bent over his instrument, his eyes focused on his fingered chords and his bow. He was oblivious to the arrival of the train. His body merged with the music and swayed. He was slender and pale, his dark hair unruly. A small shock of curls fell down over his left eye. When he leaned into the dominant notes, the curls fell across the sounding board of the instrument and he tossed them back with a flick of his head. Leela thought of a racehorse. She thought of a faun. Incongruously, she also thought of a boy she had known in childhood, a boy named Cobb, a curious boy with a curious name, a boy who had been possessed of the same skittish intensity which somehow let you know that, if cornered, this was a creature who would not yield. The violin player had Cobb’s fierce and haunted eyes.

There was no hat on the platform in front of him, no box, no can, no open violin case for donations, and the absence of any such receptacle seemed to bother the listeners. Someone tucked a folded bill into the side pocket of the violin player’s jeans but he appeared not to notice. A student in torn denim shorts took off his cloth hat and placed it beside the closed violin case as tribute and people threw coins and placed dollar bills–ones, fives, tens even–in the hat but the musician seemed indifferent and unaware. Some listeners boarded the inbound train, some seemed incapable of moving. Leela let five trains come and go, bracing herself each time against the buffeting of air. She had now worked her way forward to the innermost circle. She was four feet from the man with the violin. She could feel the intensity of his body like a series of small seismic waves against her own.

Trains arrived and departed, some people left but more gathered, the crowd around the man with the violin kept getting larger. His instrumental repertoire seemed inexhaustible–he barely paused betwe...

In this powerful and achingly beautiful novel, Janette Turner Hospital tackles head-on questions of national security, art, terrorism and love.

From the moment Leela’s ear catches the first few bars of music in between the roar of subway trains, she’s entranced by its haunting beauty. Letting the music reel her in, in perfect fifths, it’s at the end of the inbound platform that she finds Mishka Bartok, singing Che farò senza Euridice and accompanying himself on the violin. He’s surrounded by a cluster of commuters, but hardly seems to notice they are there until he stops playing. Despite Mishka’s reluctance to talk, Leela discovers that he’s a graduate student at Harvard, studying composition. She’s a mathematician at MIT, researching the math of music. Their connection is immediate, and that night they embark on a steamy love affair.

Living together in Boston, Leela and Mishka pursue their mutual passions — both academic and carnal — in a fog, as if the outside world does not exist. They have both distanced themselves from their families — Mishka from his mother and grandparents in Australia, Leela from her father and sister back in Promised Land, South Carolina. Both recoil from the reality of the city streets, where terrorists attack American civilians and a subway bombing under Harvard Square comes dangerously close to tearing their world apart. But that is ultimately the effect of the bombing, when Leela is grabbed off the street, thrust into a dark car, and taken to an interrogation room. There, she is questioned about the recent attacks by a masked man who tells her he’s a member of a private security force. He also asks directly about Mishka — who often visits an Arab café and a mosque that are under surveillance, and socializes with known instigators… all signs that he’s a terrorist, or at least aiding those responsible for the subway bombing.

When Leela’s captor removes his mask at last, Cobb stands before her: the person she was perhaps closest to as a teenager back in Promised Land. Since leaving the army, after a long stint in the Middle East, he’s been involved in paramilitary work. Cobb knows from experience that photographs can be disastrously misinterpreted, but in his eyes, Mishka is guilty. Against her instincts, Leela thinks back to Mishka’s many unexplained disappearances, often around the time of such attacks. It’s then that she realizes the mystery and intensity at the heart of their relationship could be hiding much more than she’d thought.

Mishka disappears again the next day, and doubt erodes Leela’s love as she embarks on her own investigation to find him and unravel the mystery of his life. Little does she know that her search will lead her across the globe and into an underworld of kidnapping, torture and despair.

With this compelling re-imagining of the Orpheus story, Janette Turner Hospital again shows her genius, interweaving a literary thriller with a story of passion and the triumph of decency in confusing and dangerous times. It is at once a love story on a grand scale that spans America, Australia and the Middle East, and an exploration of how ghastly side effects of terrorism can wreak havoc on individual lives.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the moment Leela’s ear catches the first few bars of music in between the roar of subway trains, she’s entranced by its haunting beauty. Letting the music reel her in, in perfect fifths, it’s at the end of the inbound platform that she finds Mishka Bartok, singing Che farò senza Euridice and accompanying himself on the violin. He’s surrounded by a cluster of commuters, but hardly seems to notice they are there until he stops playing. Despite Mishka’s reluctance to talk, Leela discovers that he’s a graduate student at Harvard, studying composition. She’s a mathematician at MIT, researching the math of music. Their connection is immediate, and that night they embark on a steamy love affair.

Living together in Boston, Leela and Mishka pursue their mutual passions — both academic and carnal — in a fog, as if the outside world does not exist. They have both distanced themselves from their families — Mishka from his mother and grandparents in Australia, Leela from her father and sister back in Promised Land, South Carolina. Both recoil from the reality of the city streets, where terrorists attack American civilians and a subway bombing under Harvard Square comes dangerously close to tearing their world apart. But that is ultimately the effect of the bombing, when Leela is grabbed off the street, thrust into a dark car, and taken to an interrogation room. There, she is questioned about the recent attacks by a masked man who tells her he’s a member of a private security force. He also asks directly about Mishka — who often visits an Arab café and a mosque that are under surveillance, and socializes with known instigators… all signs that he’s a terrorist, or at least aiding those responsible for the subway bombing.

When Leela’s captor removes his mask at last, Cobb stands before her: the person she was perhaps closest to as a teenager back in Promised Land. Since leaving the army, after a long stint in the Middle East, he’s been involved in paramilitary work. Cobb knows from experience that photographs can be disastrously misinterpreted, but in his eyes, Mishka is guilty. Against her instincts, Leela thinks back to Mishka’s many unexplained disappearances, often around the time of such attacks. It’s then that she realizes the mystery and intensity at the heart of their relationship could be hiding much more than she’d thought.

Mishka disappears again the next day, and doubt erodes Leela’s love as she embarks on her own investigation to find him and unravel the mystery of his life. Little does she know that her search will lead her across the globe and into an underworld of kidnapping, torture and despair.

With this compelling re-imagining of the Orpheus story, Janette Turner Hospital again shows her genius, interweaving a literary thriller with a story of passion and the triumph of decency in confusing and dangerous times. It is at once a love story on a grand scale that spans America, Australia and the Middle East, and an exploration of how ghastly side effects of terrorism can wreak havoc on individual lives.

From the Hardcover edition.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurW W Norton & Co Inc

- Date d'édition1900

- ISBN 10 0393065529

- ISBN 13 9780393065527

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages368

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 39,41

Frais de port :

EUR 11,74

De Royaume-Uni vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Orpheus Lost

Edité par

W W Norton & Co Inc

(2007)

ISBN 10 : 0393065529

ISBN 13 : 9780393065527

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : Brand New. 368 pages. 9.25x6.25x1.25 inches. In Stock. N° de réf. du vendeur 0393065529

Acheter neuf

EUR 39,41

Autre devise

Orpheus Lost: A Novel

Edité par

W. W. Norton & Company

(2007)

ISBN 10 : 0393065529

ISBN 13 : 9780393065527

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur Abebooks52428

Acheter neuf

EUR 56,02

Autre devise