Articles liés à Out of Place: A Memoir

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

The travails of bearing such a name were compounded by an equally unsettling quandary when it came to language. I have never known what language I spoke first, Arabic or English, or which one was really mine beyond any doubt. What I do know, however, is that the two have always been together in my life, one resonating in the other, sometimes ironically, sometimes nostalgically, most often each correcting, and commenting on, the other. Each can seem like my absolutely first language, but neither is. I trace this primal instability back to my mother, whom I remember speaking to me in both English and Arabic, although she always wrote to me in English--once a week, all her life, as did I, all of hers. Certain spoken phrases of hers like tislamli or mish "arfa shu biddi "amal? or rouh"ha--dozens of them--were Arabic, and I was never conscious of having to translate them or, even in cases like tislamli, knowing exactly what they meant. They were a part of her infinitely maternal atmosphere, which in moments of great stress I found myself yearning for in the softly uttered phrase "ya mama," an atmosphere dreamily seductive then suddenly snatched away, promising something in the end never given.

But woven into her Arabic speech were English words like "naughty boy" and of course my name, pronounced "Edwaad." I am still haunted by the memory of the sound, at exactly the same time and place, of her voice calling me "Edwaad," the word wafting through the dusk air at closing time of the Fish Garden (a small Zamalek park with aquarium) and of myself, undecided whether to answer her back or to remain in hiding for just awhile longer, enjoying the pleasure of being called, being wanted, the non-Edward part of myself taking luxurious respite by not answering until the silence of my being became unendurable. Her English deployed a rhetoric of statement and norms that has never left me. Once my mother left Arabic and spoke English there was a more objective and serious tone that mostly banished the forgiving and musical intimacy of her first language, Arabic. At age five or six I knew that I was irremediably "naughty" and at school was all manner of comparably disapproved-of things like "fibber" and "loiterer." By the time I was fully conscious of speaking English fluently, if not always correctly, I regularly referred to myself not as "me" but as "you." "Mummy doesn't love you, naughty boy," she would say, and I would respond, in half-plaintive echoing, half-defiant assertion, "Mummy doesn't love you, but Auntie Melia loves you." Auntie Melia was her elderly maiden aunt, who doted on me when I was a very young child. "No she doesn't," my mother persisted. "All right. Saleh [Auntie Melia's Sudanese driver] loves you," I would conclude, rescuing something from the enveloping gloom.

I hadn't then any idea where my mother's English came from or who, in the national sense of the phrase, she was: this strange state of ignorance continued until relatively late in my life, when I was in graduate school. In Cairo, one of the places where I grew up, her spoken Arabic was fluent Egyptian, but to my keener ears, and to those of the many Egyptians she knew, it was if not outright Shami, then perceptibly inflected by it. "Shami" (Damascene) is the collective adjective and noun used by Egyptians to describe both an Arabic speaker who is not Egyptian and someone who is from Greater Syria, i.e., Syria itself, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan; but "Shami" is also used to designate the Arabic dialect spoken by a Shami. Much more than my father, whose linguistic ability was primitive compared to hers, my mother had an excellent command of classical Arabic as well as the demotic. Not enough of the latter to disguise her as Egyptian, however, which of course she was not. Born in Nazareth, then sent to boarding school and junior college in Beirut, she was Palestinian, even though her mother, Munira, was Lebanese. I never knew her father, but he, I discovered, was the Baptist minister in Nazareth, although he originally came from Safad, via a sojourn in Texas.

Not only could I not absorb, much less master, all the meanderings and interruptions of these details as they broke up a simple dynastic sequence, but I could not grasp why she was not a straight English mummy. I have retained this unsettled sense of many identities--mostly in conflict with each other--all of my life, together with an acute memory of the despairing feeling that I wish we could have been all-Arab, or all-European and American, or all-Orthodox Christian, or all-Muslim, or all-Egyptian, and so on. I found I had two alternatives with which to counter what in effect was the process of challenge, recognition, and exposure, questions and remarks like "What are you?"; "But Said is an Arab name"; "You're American?"; "You're American without an American name, and you've never been to America"; "You don't look American!"; "How come you were born in Jerusalem and you live here?"; "You're an Arab after all, but what kind are you? A Protestant?"

I do not remember that any of the answers I gave out loud to such probings were satisfactory or even memorable. My alternatives were hatched entirely on my own: one might work, say, in school, but not in church or on the street with my friends. The first was to adopt my father's brashly assertive tone and say to myself, "I'm an American citizen," and that's it. He was American by dint of having lived in the United States followed by service in the army during World War I. Partly because this alternative meant his making of me something incredible, I found it the least convincing. To say "I am an American citizen" in an English school in wartime Cairo dominated by British troops and with what seemed to me a totally homogeneous Egyptian populace was a foolhardy venture, to be risked in public only when I was challenged officially to name my citizenship; in private I could not maintain it for long, so quickly did the affirmation wither away under existential scrutiny.

The second of my alternatives was even less successful than the first. It was to open myself to the deeply disorganized state of my real history and origins as I gleaned them in bits, and then to try to construct them into order. But I never had enough information; there were never the right number of well-functioning connectives between the parts I knew about or was able somehow to excavate; the total picture was never quite right. The trouble seemed to begin with my parents, their pasts, and names. My father, Wadie, was later called William (an early discrepancy that I assumed for a long time was only an Anglicization of his Arabic name but that soon appeared to me suspiciously like a case of assumed identity, with the name Wadie cast aside except by his wife and sister for not very creditable reasons). Born in Jerusalem in 1895--my mother said it was more likely 1893--he never told me more than ten or eleven things about his past, a series of unchanging pat phrases that hardly conveyed anything at all. He was at least forty at the time of my birth.

He hated Jerusalem, and although I was born and we spent long periods of time there, the only thing he ever said about it was that it reminded him of death. At some point in his life his father was a dragoman who because he knew German had, it was said, shown Palestine to Kaiser Wilhelm. And my grandfather--never referred to by name except when my mother, who never knew him, called him Abu-Asaad--bore the surname Ibrahim. In school, therefore, my father was known as Wadie Ibrahim. I still do not know where "Said" came from, and no one seems able to explain it. The only relevant detail about his father that my father thought fit to convey to me was that Abu-Asaad's whippings were much severer than his of me. "How did you endure it?" I asked, to which he replied with a chuckle, "Most of the time I ran away." I was never able to do this, and never even considered it.

As for my paternal grandmother, she was equally shadowy. A Shammas by birth, her name was Hanné; according to my father, she persuaded him--he had left Palestine in 1911--to return from the States in 1920 because she wanted him near her. My father always said he regretted his return home, although just as frequently he averred that the secret of his astonishing business successes was that he "took care" of his mother, and she in return constantly prayed that the streets beneath his feet would turn into gold. I was never shown her likeness in any photograph, but in my father's regimen for bringing me up she represented two contradictory adages that I could never reconcile: mothers are to be loved, he said, and taken care of unconditionally. Yet because by virtue of selfish love they can deflect children from their chosen career (my father wanted to remain in the United States and practice law), so mothers should not be allowed to get too close. And that was, is, all I ever knew about my paternal grandmother.

I assumed the existence of a longish family history in Jerusalem. I based this on the way my paternal aunt, Nabiha, and her children inhabited the place, as if they, and especially she, embodied the city's rather peculiar, not to say austere and constricted, spirit. Later I heard my father speak of us as Khleifawis, which I was informed was our real clan origin; but the Khleifawis originated in Nazareth. In the mid-1980s I was sent some extracts from a published history of Nazareth, and in them was a family tree of one Khleifi, probably my great-grandfather. Because it corresponded to no lived, even hinted-at, experience of mine, this startlingly unexpected bit of information--which suddenly gave me a whole new set of cousins--means very little to me.

My father, I know, did attend St. George's School in Jerusalem and excelled at football and cricket, making the First Eleven in both sports over successive years, as center forward and wicket keeper, respectively. He never spoke of learning anything at St. George's, nor of much else about the place, except that he was famous for dribbling a ball from one end of the field to the other, and then scoring. His father seems to have urged him to leave Palestine to escape conscription into the Ottoman army. Later I read somewhere that a war had broken out in Bulgaria around 1911 for which troops were needed; I imagined him running away from the morbid fate of becoming Palestinian cannon fodder for the Ottoman army in Bulgaria.

None of this was ever presented to me in sequence, as if his pre-American years were discarded by my father as irrelevant to his present identity as my father, Hilda's husband, U.S. citizen. One of the great set stories, told and retold many times while I was growing up, was his narrative of coming to the United States. It was a sort of official version, and was intended, in Horatio Alger fashion, to instruct and inform his listeners, who were mostly his children and wife. But it also collected and put solidly in place both what he wanted known about himself before he married my mother and what thereafter was allowed into public view. It still impresses me that he stuck to the story in its few episodes and details for the thirty-six years he was my father until his death in 1971, and that he was so successful in keeping at bay all the other either forgotten or denied aspects of his story. Not until twenty years after his death did it occur to me that he and I were almost exactly the same age when we, precisely forty years apart, came to the United States, he to make his life, I to be directed by his script for me, until I broke away and started trying to live and write my own.

My father and a friend called Balloura (no first name ever given) went first from Haifa to Port Said in 1911, where they boarded a British freighter to Liverpool. They were in Liverpool for six months before they got jobs as stewards on a passenger liner to New York. Their first chore on board was to clean portholes, but since neither of them knew what a porthole was, despite having pretended to "great sea-going experience" in order to get the jobs, they cleaned everything but the portholes. Their supervisor was "nervous" (a word my father used regularly to signify anger and general bother) about them, overturned a pail of water, and set them to floor swabbing. Wadie was then switched to waiting on tables, the only memorable aspect of which was his description of serving one course, then rushing out to vomit as the ship heaved and pitched, then staggering back to serve the next. Arriving in New York without valid papers, Wadie and the shadowy Balloura bided their time, until, on the pretext of leaving the ship temporarily to visit a nearby bar, they boarded a passing streetcar "going they had no idea where," and rode it to the end of the line.

Another of my father's much repeated stories concerned a YMCA swimming race at an upstate New York lake. This provided him with an engaging moral: he was the last to finish, but persisted to the end ("Never give up" was the motto)--in fact until the next race had already begun. I never questioned, and was duly submissive to, the packaged homily "Never give up." Then, when I was in my early thirties, it dawned on me that Wadie was so slow and stubborn he had in fact delayed all the other events, not a commendable thing. "Ne...

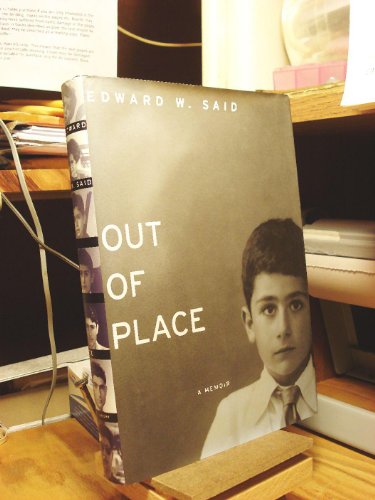

Said writes with great passion and wit about his family and his friends from his birthplace in Jerusalem, schools in Cairo, and summers in the mountains above Beirut, to boarding school and college in the United States, revealing an unimaginable world of rich, colorful characters and exotic eastern landscapes. Underscoring all is the confusion of identity the young Said experienced as he came to terms with the dissonance of being an American citizen, a Christian and a Palestinian, and, ultimately, an outsider. Richly detailed, moving, often profound, Out of Place depicts a young man's coming of age and the genesis of a great modern thinker.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurAlfred a Knopf Inc

- Date d'édition1999

- ISBN 10 0394587391

- ISBN 13 9780394587394

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Nombre de pages295

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 2,80

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Out of Place: A Memoir

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur newMercantile_0394587391

Out of Place: A Memoir

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0394587391

Out of Place: A Memoir

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover0394587391

Out of Place: A Memoir

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0394587391

Out of Place: A Memoir

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur Abebooks74899

Out of Place: A Memoir

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Buy for Great customer experience. N° de réf. du vendeur GoldenDragon0394587391

Out of Place: A Memoir

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0394587391

Out of Place: A Memoir

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Brand New!. N° de réf. du vendeur VIB0394587391

OUT OF PLACE: A MEMOIR

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.6. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-0394587391

Out of Place: A Memoir

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur Hafa_fresh_0394587391