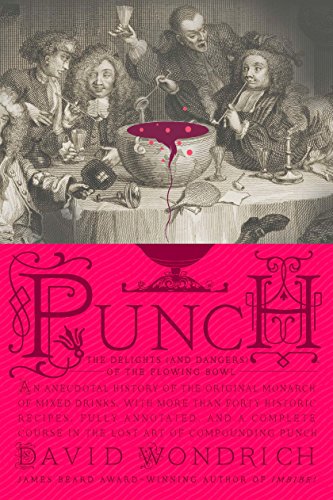

Articles liés à Punch: The Delights (and Dangers) of the Flowing Bowl

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

This book is about Punch. And by “Punch,” I don’t mean the stuff sluiced around at fraternity mixers—several 1.75-liter handles of whatever hooch is the cheapest, diluted with a random array of sodas and ersatz juices and ladled elegantly forth from a plastic trashcan. Nor do I mean the creative concoctions proffered by feature articles on stylish entertaining, the sort where a near-homeopathic quantity of liquor is thrown into a desperate rearguard action against an army of berries, tropical fruits and such, only to succumb to a fizzy wave of cheap cava. In short, there are lots of Punches this book isn’t about. But you wouldn’t expect a serious book on the Martini (such things do exist) to waste a lot of time on the so-called chocolate Martini, or in fact anything not containing gin, vermouth and practically nothing else that tries to pass itself off as a Martini—to say nothing of the “x-tini,” where x= “Mar.” And this is a serious book about Punch. Well, as serious as a book can be that tells the story of a means of communal inebriation and its associated traditions, supported by a slew of sometimes rather fiddly formulae for re-creating drinks that haven’t been tasted by humankind in at least a century and a half. In any case, it’s the first of its kind, and as such, it’s going to discriminate.

The fact that nobody’s published a real book about Punch before is in and of itself a remarkable thing. Open just about any volume written in English between the late 1600s and the mid-1800s that deals with the details of day-to-day life and odds are sooner or later somebody’s going to brew up a bowl of the stuff—Behn, Defoe, Addison & Steele, Swift, Pope, Fielding, Richardson, Smollett, Sheridan, Boswell, Burney, Edgeworth, Austen, Byron, Thackeray, Dickens, world without end. The rakes of the Restoration knew it, William and Mary’s subjects drank it readily, the reigns of the three Georges were damp with it, very damp, and the Regency was well steeped indeed. George Washington enjoyed it and Thomas Jefferson owed a part of his property to it. For some 200 years, Punch1—at base a simple combination of distilled spirits, citrus juice, sugar, water and a little spice—was the reigning monarch of the kingdom of mixed drinks. If nothing else, it has stories to tell.

Most of Punch’s stories are of warm fellowship and conviviality and high-spirited evenings afloat on oceans of witty talk. But it would be disingenuous to pretend that there aren’t also plenty of battles and brawls and all the other products of the temporary madness that overtakes even the strongest-headed when they’ve consumed more distilled spirits than they can keep track of. For every cozy evening like the ones in the settled Sussex townsman and diarist Thomas Turner used to spend, back in the days of George III, drinking Punch made from smuggled French brandy with his fellow tradesmen, there was one like Captain Drake’s in early 1709, when he sat up drinking arrack Punch with three fashionable whores in his cell in London’s Newgate prison, where he was being held for treason under arms. “On a sudden some difference arose between the ladies,” he later recalled, causing them to engage in “bloodshed and battery” until they were exhausted and their clothes and coiffures in tatters—at which point they patched themselves up as best as they could, rearranged their hair and called for another bowl.

But sufficient as it may be, the chance to retail a mess of moist anecdotes is far from the only reason to write a book about Punch. Recent years have seen public interest in the fine art of mixing drinks fizz up to an almost alarming level, spawning a number of surprisingly sober books on the subject; books that focus almost obsessively on the craft and history of the cocktail. (I myself have written three.) Almost without exception, these books have focused on the American part of the story, the part that begins with the Sling, the Cocktail, the Mint Julep and all the other ancestral “American sensations,” progenitors of pretty much every mixed drink we lap up today save vodka and Red Bull—and you could even squeeze that one in among the slings, if you were to rub it with a little Vaseline first.

We don’t know who first came up with the Julep or the Cocktail or indeed almost any of the foundational American drinks. But somebody had to teach those anonymous folk geniuses how to mix drinks. Mixology might be simple enough, as far as crafts go, but it still has its secrets, its right ways and wrong ways, tricks and traditions. Indeed, by 1803, when the cocktail first appeared in print, concerned men and women had already been grappling for two centuries and more with all the issues of balance, potency, and proper service that mixing drinks with distilled spirits raises. Admittedly, in the larger scheme of things, these are pretty trivial. Unless, that is, you’ve just laid down good coin for a drink, coin that was earned by the sweat of your brow (or whatever other part of your body you sweat with). In that case, it has real meaning whether the drink you’re about to taste was made by a ham-handed ignoramus who’s making it up as he goes along or someone who has spent a few years absorbing the best practices of the job from people who really know their onions.

In the early days of the American republic, when this quintessentially American art was first finding its legs, the best practices with which the wide-awake young men behind the bar had been indoctrinated were British, developed across the Atlantic and transplanted in American soil, and the laboratory in which they had been developed was the Punch bowl. We don’t know precisely who invented Punch in the first place, nor are we ever likely to. But we don’t know who invented the Martini, either, or the original Cocktail. Such is the history of mixed drinks. We do know that if Punch wasn’t the first mixed drink powered by distilled spirits, it was certainly the first globally popular one—spirits drinking’s killer app, as it were—and that its first unambiguous appearance in writing was in a letter by an Englishman. Whoever might have invented it, it was Englishmen, or at least Britons, who fostered the formula, spread it to their neighbors and took it all around the world.

Like all the best and most enduring culinary preparations, Punch was a simple formula that could grow in complexity with its executor’s skill and available resources. During the two centuries of its hegemony, British Punch-makers, generously endowed with both, used them to develop a good many of what we consider today to be the hallmarks of the American school of mixing drinks. The appreciation of which liquors and wines complement each other and which don’t; the ins and outs of balancing sweet and sour; the use of liqueurs and various flavored syrups for sweetening; the salutary effects of champagne and sparkling water on drink and drinker; the affinities between certain citrus fruits and certain spirits (e.g., the orange and brandy, the lime and rum); the use of eggs, dairy products and gelatin as smoothing agents—the list is both long and technical, descending into the minutiae of proportion, technique and even garnish.

The chance to explore the British foundations of modern mixology and, even better, to delve into the rich and mostly unmined quarry of anecdotes that stemmed from it, is certainly motivation enough to write a book, and, I hope, to read it. Yet there’s another, even better reason, but to explain it I’m going to have to stoop to autobiography.

How to Win Friends and Intoxicate People

Ten years ago, I fell into a job writing about cocktails. It began as an amusing sideline, something to have a little fun with while I pursued a career as professor of English literature. but it turned out mixing up Sazerac Cocktails and Green Swizzles, researching their histories and writing anecdotal little essays about them for Esquire magazine’s website was not only more fun than grading comp papers and trying to keep classes full of hormone-buzzed sophomores focused on the tribulations of King Lear, it was also—to me, anyway—considerably more satisfying. Perhaps I lacked academic seriousness. In any case, before very long the sideline metastasized into a career.

Being a professional cocktail geek brought its own peculiar challenges. one of them was what to do at parties. Spending all this time in the company of delightful drinks, I wanted to share— friends don’t let friends drink vodka tonics, not when they could be absorbing iced dew-drops crafted from good gin or straight rye whiskey, fresh-squeezed juices, rare bitters and liqueurs and, of course, lots of love. But bartending is hard work, and after a couple of years’ worth of parties spent measuring, shaking, stirring, spilling, fumbling for ingredients, fielding requests for vodka tonics and, worst of all, never getting a chance to actually talk to anyone, I was willing to relinquish the spotlight and the performative glory of mixing drinks in front of people for a little hanging out and cocktail party chitchat. Perhaps it might be time to take a second look at Punch. After all, all the old bartender’s guides I’d been steadily accumulating had clutches of large-bore recipes tucked away at the back, and if these were anything as tasty as the cocktails I’d been successfully extracting from them . . .

My first attempts to fill the Punch bowl, however, were cavalier at best. I treated the recipes as mere guidelines, changing things for convenience, cost and because surely I knew better than the mustachioed old gent who wrote the recipe. Used to making cocktails, where dilution is a no-no, I would cut back the seemingly excessive amounts of water the recipes called for. The result, of course, was chaos. I remember, dimly, one summer afternoon when I made the famous Philadelphia Fish-House Punch for the first time, leaving in the copious amounts of rum and brandy but omitting most of the water. Fortunately, it was at a house party out in the country, and nobody had to drive. Or even walk, for that matter. Even staying pantsed was somewhat of a challenge. Other times, I’d skimp on the ice, think nothing of using powdered nutmeg instead of grating it fresh, splash in Technicolor arrays of clashing liqueurs, substitute cheap bourbon for good cognac or ginger ale for champagne, and a host of other things too embarrassing to relate. Amateur stuff.

Eventually, though, I began to learn. I had help, thank God. Friends shared their expertise, their space, their liquor and, most important, themselves. It’s not Punch if there’s nobody to drink it. Ted “Dr. Cocktail” Haigh, who had put in some sterling work at the Punch bowl, was happy to share the fruits of his experience (for the record, his Bimbo Punch is a thing of beauty). Sherwin Dunner, friend to every living hot jazz musician, hosted some memorable evenings where the Punch flowed like ditchwater and the music reached an authentic speakeasy-era level of abandon. Nick Noyes and Jessica Monaco provided guinea pigs in their dozens and in their hundreds and the booze with which to water them—and, even better, an appreciation for precisely the sort of recherché, historic formulae that appealed to me. There’s something stirring about gazing across a sweeping lawn full of people all mildly intoxicated on Captain Radcliffe’s Punch, a recipe that hadn’t seen the light of day since England was ruled by a Dutchman. I could go on, but I’ll save everyone else—as many as I can remember—for the acknowledgments.

It wasn’t just laziness that kept me making Punch, although Lord knows I can be plenty lazy. But if you’re spending the hour and a half before party time assembling a baroque concoction that was originally created for European royalty and calls for fifteen ingredients, half of them prepared from other ingredients, sloth doesn’t really enter into it. Nor was it the utter deliciousness of most of these old Punches. G&Ts are delicious, too, and they take a lot less work. But over the last seven or eight years, I’ve made historic Punches dozens and dozens of times, for groups as small as four and as large as 250; for friends coming over to chat, backyard barbecues, Christmas parties, book parties, weddings (a massive bowl of Punch makes a fine wedding present, and happy wedding guests); for Victorian societies and Museums and clubs and too many lectures to count. Every time, it happens the same way.

First, while everyone else remembers those fraternal garbage cans and decides that they’ll stick to the wine, thanks anyway, the veterans, those who have shared a bowl of real Punch before, step smartly up to the sideboard and ladle themselves a cup. Meanwhile, a few adventurous or unusually bibulous newcomers sniff around the bowl, examining the unpromising, brownish liquid within (frat and food-magazine Punches are always as bright and cheerful in their coloration as drinks marketed for toddlers) and studying the vets for signs of liver disease or just plain bad character. Then one of these will give in and ladle herself a glass, taking a tentative sip as the others look on with concern. Okay, so it’s not poisonous. In fact—well, soon the knot by the bowl is making a joyful little noise and the rest of the folks are beginning to reconsider their policy of sticking to the Grüner Veltliner. One by one, what the heck, they drift over to see what the fuss is about, soon to be joined by whomever it was they were talking to before they excused themselves for the minute that has turned into ten or fifteen. Before you know it, everyone’s chattering away with tipsy animation and it’s a party. Sure, there are always a few holdouts, but sooner or later all but the most stridently resistant will get sucked in. Nobody likes to be the odd person out, particularly if all it takes to participate is to stand around sipping something truly delightful, made from a formula that Charles Dickens used to enjoy.

But that’s the true beauty of Punch. The “flowing bowl,” as its devotees used to call it, makes itself the catalyst for, and focus of, a temporary community of drinkers, not unlike the one you’ll find on a good night at a really good neighborhood pub. Admittedly, some will have drunk a little more than they’re used to; the limpid balance of good Punch makes that easy. One or two might have been grievously overserved, but if so, it was by their own hands. the Punch bowl holds dangers as well as delights; it is freedom, and freedom is a test that some must fail. But Punch isn’t cocktails. The cocktail is an unforgiving drink, with a very narrow margin of safety. Two Martinis and you’re fine, three and you’re on the redeye to Drunkistan. The little glasses of Punch—the traditional serving is about a sherry-glass full; just a couple of ounces—mount up, to be sure, but it’s easy to pull back before you’ve gone too far. Whatever their octane, though, there’s something particularly exhilarating to drinks based on distilled spirits, and Punch will always share that. as the eighteenth-century song put it:

You may talk of brisk Claret, sing Praises of Sherry,

Speak well of old Hock, Mum, Cider and Perry;

But you must drink Punch if you mean to be Merry.

There’s the crux. Without merriment, life is scarcely worth living. I know th...

-Bookforum

"Most punches have fascinating back stories - at least they do when Wondrich is in charge."

-The New York Times Book Review

"Mr. Wondrich's noble effort to restore Punch's good name offers sound advice on the basics of Punch-making along with a variety of vintage recipes."

-The Wall Street Journal

"A lively, fascinating history of punch[...]. Wondrich is a tremendously witty writer."

-The New Yorker

"Wondrich peels punch's image off the sticky fraternity house floor and reinstates it into the more dignified annals of drinking tradition."

-The Boston Globe

"It's fair to say there's nobody in the country who knows more about drinking than David Wondrich."

-New York Magazine

"Punch stays true to the antique, but by no means staid, spirit of its old timey, black-and-white-etching-illustrated subject matter, while somehow managing to keep current, relevant, and fresh. [...] A rollickingly fun read."

-TheKitchn.com

"[Wondrich's] interest in history runs as deep as his thirst for beverage experiences on the banks of the mainstream[...]."

-The New York Times

"Punch lovers are in luck[...]. These aren't the fruity, simplistic punches of recent times. They're complex, subtle concoctions...."

-The Oregonian

"The best part of the book isn't the history-it's the 40-plus detailed recipes of how to make your very own authentic Punch."

-The New York Post

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurTarcherPerigee

- Date d'édition1999

- ISBN 10 0399536167

- ISBN 13 9780399536168

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages320

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Punch: The Delights (and Dangers) of the Flowing Bowl

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur DADAX0399536167

Punch: The Delights (and Dangers) of the Flowing Bowl

Description du livre Etat : New. Book is in NEW condition. N° de réf. du vendeur 0399536167-2-1