Articles liés à Such Troops as These: The Genius and Leadership of...

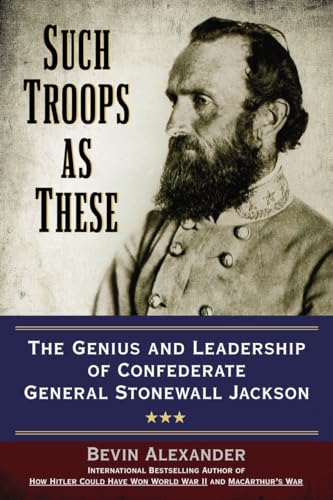

Such Troops as These: The Genius and Leadership of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson - Couverture souple

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNMAPS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am extremely grateful to Natalee Rosenstein, vice president and senior executive editor of the Berkley Publishing Group, for her splendid, insightful, and discerning support of this project. It has been a pleasure working with her and with Robin Barletta, editorial assistant at Berkley. Robin is a most remarkably sensitive, understanding, and efficient person who expedited the project most wonderfully. She corrected all my errors, removed all roadblocks, and turned the entire endeavor into an adventure.

Richard Hasselberger produced a superb cover design that conveys the content of the book most effectively. Laura K. Corless conceived a tasteful and truly beautiful design for the interior text. My longtime cartographer, Jeffrey L. Ward, drew the exceptionally accurate maps that allow the reader to follow exactly where the actions took place. Clear and comprehensible maps are mandatory for understanding military operations, and Jeffrey, in my opinion, draws the best maps in America today.

I have relied for a long time on my agent, Agnes Birnbaum, for her friendship, sage advice, and surpassing knowledge of the publishing industry, but mostly for the inspiring example she presents of a caring and considerate human being.

Finally, I am most honored that my sons Bevin Jr., Troy, and David, and my daughters-in-law, Mary and Kim, have always supported me steadfastly in my long and exhausting writing ventures.

INTRODUCTION

Jackson’s Recipes for Victory

Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson was a unique, incredibly complicated figure. He was committed to his Presbyterian religious faith, devoted to his second wife, so reserved that even his close friends seldom knew what he was thinking, dedicated to duty and the cause of Southern independence, and by far the greatest general ever produced by the American people.

Very early, Jackson discerned a way for the South to win the Civil War with speed and few losses. He recognized that the North, with three times the population of the South and eleven times its industry, was so sure of victory that it had sent practically all of its military forces into the South and had left the North almost entirely undefended. The only thing the South had to do to win, Jackson saw, was to invade the eastern states of the Union, where the vast majority of Northern industry was located and where most of its population resided. Before any Union armies could be extricated from the South, Confederate troops could cut the single railway corridor connecting Washington with Northern states, force the Abraham Lincoln administration to abandon the capital, and, by threatening the railroads, factories, farms, and mines along the great industrial corridor from Baltimore to southern Maine, compel the Northern people to give up the struggle.

A similar assault on Southern economic prosperity was precisely the strategy that Lincoln was using to conquer the South. But the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, was a decidedly third-rate leader who possessed extremely little vision or imagination. He was committed to passive defense of the South, despite the fact that it was guaranteed to fail.1 Davis refused to endorse Jackson’s strategy, although he pressed it on Davis four times.

Once Jackson realized that Davis was never going to authorize a decisive invasion of the North, he developed another method of winning the war. He saw that two new weapons had made attacks against defended positions almost certain to fail. The first weapon was the single-shot Minié-ball rifle, with a range four times that of the old standard infantry weapon, the smoothbore musket. The second was the lightweight “Napoleon” cannon (named after Napoleon III, not the emperor) that could be rolled up to the firing line and could spew out clouds of deadly metal fragments called canister into the faces of advancing enemy troops. Jackson saw that the South could be victorious if it induced Northern armies to attack well-emplaced Confederate positions. The Union armies would inevitably be defeated, and the Confederates could swing around the flank of the demoralized Northerners and force them into retreat or surrender.

None of the other commanders on either side identified the revolutionary implications of these two weapons, however, and Jackson had an extremely difficult time trying to convince the senior Confederate commander in the East, Robert E. Lee, to follow his new system.

Jackson recognized that there is only one fundamental principle of military strategy, or the successful conduct of war. It is to attack the enemy where he is not. That is, to exert force where there is little or no opposition. All the other axioms of warfare can be reduced to variations on this single elementary theme. The ancient Chinese military sage Sun Tzu encapsulated the idea in a single sentence around 400 B.C.: “The way to avoid what is strong is to strike what is weak.”2 Jackson knew nothing of Sun Tzu, but he developed the same understanding on his own.

This is an extremely difficult concept to get across, however. Warfare to most people does not seem to be so simple. They view it through the lens of very different experiences. Human beings built their concept of warfare in the Stone Age. The small bands and tribes into which the human race was divided found that direct confrontation was the most likely way to deter opposing bands and tribes from encroaching on their safe havens and hunting grounds.3 We have carried this concept of frontal challenge forward into modern times. It is deeply ingrained in the human psyche. We label persons who act otherwise as sly and shifty; we say that they blindside other people, that they stab them in the back. We revile and despise such people, while we admire people who act in a direct, straightforward manner.

Over the aeons, highly observant individuals have occasionally seen, however, that indirection is the most effective way to achieve success, in military and in other matters, and they have attacked their opponent’s weakness. But these have been rare occurrences. In times of stress we usually revert to the instinctive response we learned in the Stone Age. We challenge the opponent right in front of us.

Therefore it is the extraordinary person who can avoid straight confrontation and can recognize the wisdom of Sun Tzu, who said: “All warfare is based on deception.”4 Stonewall Jackson was such an extraordinary person. And he saw clearly ways to win by going around the enemy, not confronting him headlong.

The Civil War of 1861–65 was the greatest crisis ever to befall the American Union. This war pitted the industrial North against the agricultural South. Though the population of the United States in 1860 was only 31.5 million people, less than a tenth of what it is today, 600,000 men were killed in the war, far more than in any other war in American history, including World War II.

The primary fact about the South was that it was an overwhelmingly agrarian, preindustrial society within a larger society that was rapidly industrializing. Because of the railroad, this larger industrial society was spreading its influence and power over the entire country. Until the coming of the railroads in the 1840s, North and South had been able to maintain radically different economies without great conflict because they interacted with each other largely at the peripheries.

For example, New England was developing a textile industry that used Southern cotton as its main feedstock. But, because roads were atrocious, it was easier to import cotton from the South and to export finished textiles to the South by ship rather than by land. Therefore, New England competed directly with Britain for the South’s raw cotton and for the South’s finished textile trade. This competition kept cotton prices high and finished product prices low. Much the same was true of iron and steel. The North produced some metal products, but it competed directly with Britain’s vast iron and steel industry.

By 1860, however, the extension of the railroads had made feasible the economical shipping of Northern industrial products throughout the country. This had aroused a tremendous move in the North to establish high tariffs to protect Northern industry from the far larger and more proficient British factories. In other words, Northern industrialists wanted to create a closed American economy in which only their products would be available. And these products would cost more than British products because American industry was newer and less efficient than British industry. The South was being asked to pay to strengthen Northern industry, while at the same time it was being asked to weaken Britain, by far the greatest market for its cotton. Also, Northern textile manufacturers, with reduced competition from Britain, would have to pay less for Southern cotton. Since, therefore, a high tariff would directly damage Southern pocketbooks, Southerners were violently opposed to it—and this conflict played an important role in the division of North and South.

The key immediate dispute, however, was over the continued bondage of 3.5 million black slaves in fifteen Southern states. Only a fraction of the Southern people owned slaves. Of the 1.6 million white families in 1860, only one in four owned any slaves, and only 133,000 owned ten or more slaves, or about one family in thirteen. Only 7,000 families owned fifty or more slaves, or one family in 228.5 The overwhelming majority of slaves were owned by an extremely small, wealthy aristocracy that possessed most of the good farmland and that dominated the South politically.

Although slavery was extremely controversial, and people North and South knew it was evil and had to be ended, it was the foundation of Southern agriculture. Cotton, produced largely on big plantations in the Deep South, constituted by far the greatest portion of the region’s wealth. The Industrial Revolution had not mechanized agriculture to any substantial degree, and farmers and planters relied overwhelmingly on hand labor to produce all crops, but most especially cotton, whose fiber bolls had to be picked one at a time. Therefore, eliminating slavery in one swift process would devastate the South’s economy, and, if slave owners were not compensated, would not only impoverish the elite landed aristocracy, but also the overwhelming bulk of the Southern people, white and black.

The only equitable solution was to pay the owners the value the slaves represented. But the politicians of the North were not inclined to induce the Northern people to foot most of the cost of such a transformation. This was a profoundly wrong decision, for the cost of the conflict in money alone—not to speak of the human cost and the social upheaval that it caused—was at least twice what it would have taken to purchase all of the slaves and give every freed family forty acres and a mule.6

The issue came to a head in the presidential election of 1860. Abolitionists, who were pushing for an immediate end of slavery and nothing for the planters, gained momentum, and an antislavery Republican, Abraham Lincoln, won the election. Southern planters feared he would force through laws demanded by the abolitionists.

No aristocracy ever voluntarily gives up its privileges. Every aristocracy is willing to bring down the entire social edifice to preserve its favored position. The British aristocrats refused to grant the American colonies any political rights. This set off the American Revolution of 1775 to 1783, causing the aristocrats to lose the greatest empire Britain ever possessed. The French aristocracy refused to offer the peasants and the merchants any rights and brought on the French Revolution of 1789, which destroyed the aristocracy but also threw French society into chaos.

The Southern aristocrats were no different from their British and French counterparts. Since they controlled the political fortunes of the Deep South, they passed secession ordinances in the seven Deep South states in late 1860 and early 1861. These acts catered to the aristocrats’ economic interests, and also reflected their belief that the Constitution gave them the legal right to do so. Lincoln denied this right, and in April 1861, he called on the remaining states to quash what he called the “rebellion” of these seven states. Forced to choose between Lincoln’s demand and what they believed to be morally correct and honorable, four Upper South states that had remained steadfastly loyal—North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and Arkansas—refused to accept the idea of forcing their “erring sisters” back into the Union at the bayonet’s point, and seceded as well.

The entire issue of the Civil War was summarized brilliantly by an astute South Carolina woman, Mary Boykin Chesnut (1823–86), wife of a U.S. senator who became a Confederate officer. She wrote in her diary on July 8, 1862: “This war was undertaken by us to shake off the yoke of foreign invaders, so we consider our cause righteous. The Yankees, since the war has begun, have discovered it is to free the slaves they are fighting, so their cause is noble.”7

With both sides so starkly divided regarding even what the war was all about, there was little hope of compromise. Each side was convinced of the justice of its cause. The war was going to be pursued to the bitter end.

This book is a very human story of Stonewall Jackson, who was caught in the vortex of this great crisis, and of how he made the judgments that could have won the war for the South and prevented the South from descending into catastrophe. In carrying out his mission, Jackson demonstrated a transcendent superiority over every other general he encountered. He ranks as one of the supreme military geniuses in world history. Unfortunately for the South, the Confederacy was ruled by leaders who possessed none of Jackson’s vision.

CHAPTER 1

The Making of a Soldier

Thomas Jonathan Jackson was born January 21, 1824, in Clarksburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), into a family that was beset with tragedy. On March 6, 1826, when Thomas was two years old and his brother Warren was five years old, his sister Elizabeth, six years old, died of typhoid fever. Only twenty days later his father, Jonathan, an unsuccessful attorney, also died of typhoid fever. The very next day, Thomas’s mother, Julia, gave birth to a daughter, who was named Laura.1

Julia, twenty-eight years old, was left destitute with two small boys and an infant daughter. She had to give up her home and nearly all of her resources to pay off her husband’s debts. She barely supported herself and her family by moving to a donated one-room cottage, where she took in sewing and taught paying children school. Julia herself began to weaken with the first signs of tuberculosis. Realizing that her health was slipping, Julia married Blake B. Woodson, an attorney fifteen years her senior, in 1830.

The next year Woodson became clerk of court of newly created Fayette County, in the high mountains 125 miles south of Clarksburg. The family moved to the county seat of Ansted, but Julia’s health was now deteriorating badly, and she was forced to send her son Warren, now ten years o...

The Civil War pitted the industrial North against the agricultural South, and remains one of the most catastrophic conflicts in American history. With triple the population and eleven times the industry, the Union had a decided advantage over the Confederacy. But one general had a vision that could win the War for the South—Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson.

Jackson believed invading the eastern states from Baltimore to Maine could divide and cripple the Union, forcing surrender, but failed to convince Confederate president Jefferson Davis or General Robert E. Lee.

In Such Troops as These, Bevin Alexander presents a compelling case for Jackson as the greatest general in American history. Fiercely dedicated to the cause of Southern independence, Jackson would not live to see the end of the War. But his military legacy lives on and finds fitting tribute in this book.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurDutton Caliber

- Date d'édition2015

- ISBN 10 0425271307

- ISBN 13 9780425271308

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages336

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,97

De Canada vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Such Troops as These: The Genius and Leadership of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : New. Paperback. Publisher overstock, may contain remainder mark on edge. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780425271308B

Such Troops as These Format: Paperback

Description du livre Etat : New. Brand New. N° de réf. du vendeur 0425271307

Such Troops as These: The Genius and Leadership of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson

Description du livre Etat : New. Book is in NEW condition. N° de réf. du vendeur 0425271307-2-1

Such Troops as These: The Genius and Leadership of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson

Description du livre Etat : New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-0425271307-new

Such Troops As These (Paperback)

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Paperback. Acclaimed military historian Bevin Alexander offers a fresh and cogent analysis of Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's military genius and explores how the Civil War might have ended differently if Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee had adopted Jackson's bold alternative strategies.Acclaimed military historian Bevin Alexander offers a provocative analysis of Stonewall Jackson's military genius and reveals how the Civil War might have ended differently if Jackson's strategies had been adopted.The Civil War pitted the industrial North against the agricultural South, and remains one of the most catastrophic conflicts in American history. With triple the population and eleven times the industry, the Union had a decided advantage over the Confederacy. But one general had a vision that could win the War for the South-Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson.Jackson believed invading the eastern states from Baltimore to Maine could divide and cripple the Union, forcing surrender, but failed to convince Confederate president Jefferson Davis or General Robert E. Lee.In Such Troops as These, Bevin Alexander presents a compelling case for Jackson as the greatest general in American history. Fiercely dedicated to the cause of Southern independence, Jackson would not live to see the end of the War. But his military legacy lives on and finds fitting tribute in this book. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780425271308

Such Troops as These: The Genius and Leadership of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson

Description du livre Etat : New. 336. N° de réf. du vendeur 26372302630

Such Troops as These: The Genius and Leadership of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0425271307

Such Troops as These: The Genius and Leadership of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Buy for Great customer experience. N° de réf. du vendeur GoldenDragon0425271307

Such Troops As These: The Genius and Leadership of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson

Description du livre Paperback / softback. Etat : New. New copy - Usually dispatched within 4 working days. N° de réf. du vendeur B9780425271308

Such Troops as These: The Genius and Leadership of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0425271307