Articles liés à Escape

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNI was born in the bitter cold but into warm and loving hands. Aunt Lydia Jessop was the midwife who brought me into the world on January 1, 1968, just two hours after midnight.

Aunt Lydia could not believe I’d survived. She was the midwife who had delivered babies for two generations, including my mother. When she saw the placenta, she realized that my mother had chronic placental abruption. Mom had hemorrhaged throughout her pregnancy and thought she was miscarrying. But when the bleeding stopped, she shrugged it off, assuming she was still pregnant. Aunt Lydia, the midwife, said that by the time I was born, the placenta was almost completely detached from the uterus. My mother could have bled to death and I could have been born prematurely or, worse, stillborn.

But I came into the world as a feisty seven-pound baby, my mother’s second daughter. My father said she could name me Carolyn or Annette. She looked up both names and decided to call me Carolyn because it meant “wisdom.” My mother always said that even as a baby, I looked extremely wise to her.

I was born into six generations of polygamy on my mother’s side and started life in Hildale, Utah, in a fundamentalist Mormon community known as the FLDS, or the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Polygamy was the issue that defined us and the reason we’d split from the mainstream Mormon Church.

My childhood memories really begin in Salt Lake City. We moved there when I was about five. Even though my parents believed in polygamy, my father had only one wife. He owned a small real estate business that was doing well and decided it made sense to use Salt Lake as a base. We had a lovely house with a porch swing and a landscaped yard and trees. This was a big change from the tiny house in Colorado City with dirt and weeds in the yard and a father who was rarely home.

But the biggest difference in moving to Salt Lake City was that my mother, Nurylon, was happy. She loved the city and delighted in having my father home every night after work. My dad was doing well, and Mom had enough money to buy plenty of groceries when we went to the store and even had some extra for toys.

There were soon four of us. I had two sisters, Linda and Annette. I was in the middle–Linda was eighteen months older than I and Annette two years younger. My baby brother Arthur arrived a few years after Annette. My mother was thrilled to finally have a son because in our culture, boys have more value than girls. Linda and my mother were very close. But my mother always seemed very irritated by me, in part, I think, because I was my father’s favorite.

I adored my dad, Arthur Blackmore. He was tall and thin, with large bones and dark, wavy hair. I remember that whenever we were around other families I thought I had the best-looking father in the entire world. I saw him as my personal protector and felt safe when I was in his presence. His face lit up when I entered the room; I was always the daughter he wanted to introduce when friends visited our house. My mother complained that he didn’t discipline me as much as he did my sister Linda, but he ignored her and didn’t seem to care.

We only lived in Salt Lake City for a year, but it was a happy one. Mother took us to the zoo and to the park, where we’d play on the swings and slides. My father’s business was successful and expanding. But he decided we needed to move back to Colorado City, Arizona—a tiny, nondescript FLDS enclave about 350 miles south of Salt Lake City and a stone’s throw from Hildale, Utah, where I was born. The reason we went back was that he didn’t want my sister Linda attending a regular public school. Even though she would technically be going to a public school in Colorado City, most of the teachers there were FLDS and very conservative. In theory, at least, religion is not to be taught in public schools, but in fact it was an integral part of the curriculum there.

When we returned to Colorado City, my father put an addition onto our house. There was more space to live in, but life became more claustrophobic. Mother changed. When we got up in the morning, she would still be sleeping. My father was on the road a lot now, so she was home alone. When we tried to wake her up, she’d tell us to go back to bed.

She’d finally surface midmorning and come into the kitchen to make us breakfast and talk about how much she wanted to die. While she made us hot cornmeal cereal, toast, or pancakes she’d complain about having nothing to live for and how she’d rather be dead. Those were the good mornings. The really awful mornings were the ones when she’d talk about how she was going to kill herself that day.

I remember how terrified I felt wondering what would happen to us if my mother killed herself. Who’d take care of us? Father was gone nearly all the time. One morning I asked my mother, “Mama, if a mother dies, what will happen to her children? Who will take care of them?”

I don’t think Mother noticed my urgency. She had no idea of the impact her words had been having on me. I think she felt my question arose from a general curiosity about dying. Mother was very matter–of–fact in responding to me: “Oh, the children will be all right. The priesthood will give their father a new wife. The new wife will take care of them.”

By this time I was about six. I looked at her and said, “Mama, I think that Dad better hurry up and get a new wife.”

I was beginning to notice other things about the world around me. One was that some of the women we’d see in the community when we went shopping were wearing dark sunglasses. I was surprised when a woman took her glasses off in the grocery store and I could see that both her eyes were blackened. I asked my mother what was wrong, but the question seemed to make her uncomfortable and she didn’t answer me. My curiosity was piqued, however, and every time I saw a woman in dark glasses, I stared at her to see if they were covering strange, mottled bruises.

What I did love about my mother was her beauty. In my eyes, she was gorgeous. She dressed with pride and care. Like my father, she was tall and thin. The clothes she made for herself and my sisters and me were exquisite. She always picked the best fabrics. She knew how to make pleats and frills. I remember beaming when someone would praise my mother for her well–mannered and well–dressed children. Everyone in the community thought she was an exceptional mother.

But that was the public façade. In private, my mother was depressed and volatile. She beat us almost every day. The range was anything from several small swats on the behind to a lengthy whipping with a belt. Once the beating was so bad I had bruises all over my back and my legs for more than a week. When she hit us, she accused us of always doing things to try to make her miserable.

I feared her, but my fear made me a student of her behavior. I watched her closely and realized that even though she slapped us throughout the day, she never spanked us more than once a day. The morning swats were never that intense or prolonged. The real danger came in late afternoon, when she was in the depths of her sorrow.

I concluded that if I got my spanking early in the morning and got it out of the way, I would basically have a free pass for the rest of the day. As soon as Mama got up, I knew I had a spanking coming. Linda and Annette quickly caught on to what I was doing, and they tried to get their spankings out of the way in the morning, too.

There were several times when my mother spanked me and then screamed and screamed at me. “I’m going to give you a beating you’ll never forget! I am not going to stop beating you until you shut up and stop crying! You make me so mad! How could you be so stupid!” Even though it’s been decades, her screams still echo inside me when I think about her.

I remember overhearing my mother say to a relative, “I just don’t understand what has gotten into my three daughters. As soon as I am out of bed every morning, they are so bad that no matter how much I warn them, they will just not be quiet until I give them all a spanking. After they have all gotten a spanking, then everything calms down and we can all get on with our day.”

When my mother beat me, she would always say she was doing it because she loved me. So I used to wish that she didn’t love me. I was afraid of her, but I would also get angry at her when she hit me. After she beat me she insisted on giving me a hug. I hated that. The hug didn’t make the spanking stop hurting. It didn’t fix anything.

I never told my father about the beatings because it was such an accepted part of our culture. What my mother was doing would be considered “good discipline.” My mother saw herself as raising righteous children and felt teaching us obedience was one of her most important responsibilities. Spanking your children was widely seen as the way to reach that goal. It wasn’t considered abuse; it was considered good parenting.

Some of the happiest times for me would be when we would have quilting parties at home. The women from the community would spend the day at our house, quilting around a big frame. Stories and gossip were shared, there was a lot of food, and the children all had a chance to play together. Quilting parties were the one time we had breathing room.

Once I was playing with dolls with my cousin under the quilt when I heard my aunt Elaine say, “I was so scared the other day. Ray Dee was playing out in the yard with her brothers and sisters. Some people from out of town stopped in front of our house. All of the other children ran into the house screaming, but Ray Dee stayed outside and talked to the out–of–towners.”

Aunt...

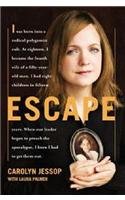

The dramatic first-person account of life inside an ultra-fundamentalist American religious sect, and one woman’s courageous flight to freedom with her eight children.

When she was eighteen years old, Carolyn Jessop was coerced into an arranged marriage with a total stranger: a man thirty-two years her senior. Merril Jessop already had three wives. But arranged plural marriages were an integral part of Carolyn’s heritage: She was born into and raised in the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS), the radical offshoot of the Mormon Church that had settled in small communities along the Arizona-Utah border. Over the next fifteen years, Carolyn had eight children and withstood her husband’s psychological abuse and the watchful eyes of his other wives who were locked in a constant battle for supremacy.

Carolyn’s every move was dictated by her husband’s whims. He decided where she lived and how her children would be treated. He controlled the money she earned as a school teacher. He chose when they had sex; Carolyn could only refuse—at her peril. For in the FLDS, a wife’s compliance with her husband determined how much status both she and her children held in the family. Carolyn was miserable for years and wanted out, but she knew that if she tried to leave and got caught, her children would be taken away from her. No woman in the country had ever escaped from the FLDS and managed to get her children out, too. But in 2003, Carolyn chose freedom over fear and fled her home with her eight children. She had $20 to her name.

Escape exposes a world tantamount to a prison camp, created by religious fanatics who, in the name of God, deprive their followers the right to make choices, force women to be totally subservient to men, and brainwash children in church-run schools. Against this background, Carolyn Jessop’s flight takes on an extraordinary, inspiring power. Not only did she manage a daring escape from a brutal environment, she became the first woman ever granted full custody of her children in a contested suit involving the FLDS. And in 2006, her reports to the Utah attorney general on church abuses formed a crucial part of the case that led to the arrest of their notorious leader, Warren Jeffs.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurViking

- Date d'édition2007

- ISBN 10 0670917214

- ISBN 13 9780670917211

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages432

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,74

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Escape

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0670917214