Articles liés à The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

At the close of the twentieth century, the female body poses an enormous problem for American girls, and it does so because of the culture in which we live. The process of sexual maturation is more difficult for girls today than it was a century ago because of a set of historical changes that have resulted in a peculiar mismatch between girls' biology and today's culture. Although girls now mature sexually earlier than ever before, contemporary American society provides fewer social protections for them, a situation that leaves them unsupported in their development and extremely vulnerable to the excesses of popular culture and to pressure from peer groups. But the current body problem is not just an external issue resulting from a lack of societal vigilance or adult support; it has also become an internal, psychological problem: girls today make the body into an all-consuming project in ways young women of the past did not.

A century ago, American women were lacing themselves into corsets and teaching their adolescent daughters to do the same; today's teens shop for thong bikinis on their own, and their middle-class mothers are likely to be uninvolved until the credit card bill arrives in the mail. These contrasting images might suggest a great deal of progress, but American girls at the end of the twentieth century actually suffer from body problems more pervasive and more dangerous than the constraints implied by the corset. Historical forces have made coming of age in a female body a different and more complex experience today than it was a century ago. Although sexual development--the onset of menstruation and the appearance of breasts--occurs in every generation, a girl's experience of these inevitable biological events is shaped by the world in which she lives, so much so, that each generation, at its own point in history, develops its own characteristic body problems and projects. Every girl suffers some kind of adolescent angst about her body; it is the historical moment that defines how she reacts to her changing flesh. From the perspective of history, adolescent self-consciousness is quite persistent, but its level is raised or lowered, like the water level in a pool, by the cultural and social setting.

Back in the 1830s, Victoria, the future queen of England, became intensely self-conscious about her body at the age of fifteen and sixteen, and although her first menstrual period was never announced officially, it was generally known that Victoria crossed the threshold into womanhood at about that time. At age eighteen, before she became queen, Victoria expressed general dissatisfaction with her looks. She mused over her hair, which was getting too dark; her hands, which she considered ugly; and her eyebrows, which she thought so inadequate that she considered shaving them off in order to encourage their growth. She also made awkward attempts to disguise her physical flaws: she tried covering up her stubby fingers with rings, but then found she had difficulty wearing gloves, which were obligatory for someone of her status. Some of Victoria's self-consciousness was a response to the attention she received as a future monarch. But it also had to do with the biological changes of adolescence, changes that breed both awkwardness and awe. The American poet Lucy Larcom, who tended looms in the textile mills of nineteenth-century New England, lived a life vastly different from Victoria's, but she, too, became "morbidly self-critical" in adolescence. When her body began to change visibly, her older sisters insisted that she lengthen her skirts and put up her hair--markers of sexual maturation in those days.1

Almost a century later, in the 1920s, the feminist writer and philosopher Simone de Beauvoir ruminated about her changing body. At fifteen she thought she looked simply "awful." She had acne, her clothes no longer fit, and she had to wrap her breasts in bandages because her favorite beige silk party dress pulled so tightly across her new bosom that it looked "obscene." Later in life, de Beauvoir described adolescence as a "difficult patch."2

Although Margaret Mead's 1928 classic Coming of Age in Samoa suggested that there are cultures where girls do not experience self-consciousness in adolescence or discomfort with their changing bodies, in the United States and in Western Europe they clearly have experienced both for at least a century.3 A matronly queen, a popular poet, and a mature feminist--each left indications that she felt self-conscious in adolescence, as most girls do.

In the nineteenth century, the "growing pains" of adolescence were diminished by society's emphasis on spiritual rather than physical matters. There were rigid standards of decorum that made discussion of the body "impolite." Yet among girls in the middle and upper classes, there was concern about the size of certain body parts, such as the hands, feet, and waist. To be too large or too robust was a sign of indelicacy that suggested lower-class origins and a rough way of life. Even the exalted Victoria and her mother, the Duchess of Kent, worried about body size. Victoria's feet were admirable because they were tiny; yet she was warned periodically by her mother against becoming too stout, and she was chided for eating too much. A future queen, after all, was not supposed to look like a husky milkmaid or mill girl, and her body must never imply that she did demanding physical labor.4

Still, there is an important difference between the past and the present when it comes to the level of social support for the adolescent girl's preoccupation with her body. Beauty imperatives for girls in the nineteenth century were kept in check by consideration of moral character and by culturally mandated patterns of emotional denial and repression.5 Nineteenth-century girls often noted in their diaries when they acquired an exciting personal embellishment, such as a hair ribbon or a new dress, but these were not linked to self-worth or personhood in quite the ways they are today. In fact, girls who were preoccupied with their looks were likely to be accused of vanity or self-indulgence. Many parents tried to limit their daughters' interest in superficial things, such as hairdos, dresses, or the size of their waists, because character was considered more important than beauty by both parents and the community. And character was built on attention to self-control, service to others, and belief in God--not on attention to one's own, highly individualistic body project.

Good Works Versus Good Looks

The traditional emphasis on "good works" as opposed to "good looks" meant that the lives of young women in the nineteenth century had a very different orientation from those of girls today. This difference is reflected in the tone of their personal diaries, a source I use extensively to tell the story of how the American girl's relationship to her body has changed over the past century. Before World War I, girls rarely mentioned their bodies in terms of strategies for self-improvement or struggles for personal identity. Becoming a better person meant paying less attention to the self, giving more assistance to others, and putting more effort into instructive reading or lessons at school. When girls in the nineteenth century thought about ways to improve themselves, they almost always focused on their internal character and how it was reflected in outward behavior. In 1892, the personal agenda of an adolescent diarist read: "Resolved, not to talk about myself or feelings. To think before speaking. To work seriously. To be self restrained in conversation and actions. Not to let my thoughts wander. To be dignified. Interest myself more in others."6

A century later, in the 1990s, American girls think very differently. In a New Year's resolution written in 1982, a girl wrote: "I will try to make myself better in any way I possibly can with the help of my budget and baby-sitting money. I will lose weight, get new lenses, already got new haircut, good makeup, new clothes and accessories."7 This concise declaration clearly captures how girls feel about themselves in the contemporary world. Like many adults in American society, girls today are concerned with the shape and appearance of their bodies as a primary expression of their individual identity.

At the end of the twentieth century, the body is regarded as something to be managed and maintained, usually through expenditures on clothes and personal grooming items, with special attention to exterior surfaces--skin, hair, and contours. In adolescent girls' private diaries and journals, the body is a consistent preoccupation, second only to peer relationships. "I'm so fat. [Hence] I'm so ugly," is as common a comment today as are classic adolescent ruminations about whether Jennifer is a true friend, or if Scott likes Amy.

In my role as a teacher of women's history and women's studies at Cornell University, I have heard variations of this kind of "body talk" for almost two decades. It usually takes the form of offhand comments, but it recently surfaced in a seminar discussion about the health of women and girls in the nineteenth century. Clad in a variety of comfortable clothes, ranging from leggings and jeans to baggy sweaters and dresses, my students deplored the corset and lamented the constraints Victorian society imposed on women. Clearly, they considered themselves much better off than the young women who had braved public criticism to study at Cornell a century earlier.

Then the conversation drifted to the present, and somehow we ended up talking about a current body project that I had known little about. My students told me how they remove pubic hair in order to wear the newest, most minimal bikinis. As we talked, a few uttered a disapproving "No way" or "Ouch," but others felt compelled to offer a rationale for this delicate procedure. "It's necessary," they said, "so you can feel confident at the beach." Although they admitted that male ogling made them nervous, they also regarded the ability to display their bodies as a sign of women's liberation, a mark of progress, and a basic American right. Madonna was mentioned as a model: she keeps her body absolutely hairless, my students assured me, and she retains a highly paid, personal cosmetologist to do the job.

These young women were bright enough to gain admission to an Ivy League university, and they enjoyed educational opportunities unknown to earlier generations. But they also felt a need to strictly police their bodies. I was intrigued by both their discreet euphemism for genitalia--"bikini-line area"--and their willingness to add yet another body concern to the already substantial litany of adolescent anxieties: hair, pimples, thighs. We talked some more, and I offered my perspective as a historian and feminist, but also as a grandmother. Life in the world of the microbikini is obviously different from life in the world of the corset, I argued, but there are still constraints and difficulties, perhaps even greater ones. Today, unlike in the Victorian era, commercial interests play directly to the body angst of young girls, a marketing strategy that results in enormous revenues for manufacturers of skin and hair products as well as diet foods.8 Although elevated body angst is a great boost to corporate profits, it saps the creativity of girls and threatens their mental and physical health. Progress for women is obviously filled with ambiguities.

What makes the situation today especially urgent, however, is that the problem begins so early in life, when the female body first begins to gear up for reproduction. Puberty begins earlier today, which means that girls must cope with menstruation and other aspects of physical maturation at a younger age, when they are really still children emotionally. Until puberty, girls really are the stronger sex in terms of standard measures of physical and mental health: they are hardier, less likely to injure themselves, and more competent in social relations. But as soon as the body begins to change, a girl's advantage starts to evaporate. At that point, more and more girls begin to suffer bouts of clinical depression. The explanation of this sex difference lies in the frustrations girls feel about the divergence between their dreams for the future and the conventional sex roles implied by their emerging breasts and hips.9

In addition to an increasing risk of depression and suicide attempts, adolescent girls today are more vulnerable than boys of the same age to eating disorders, substance abuse, and dropping out of school. And of course, early childbearing has a greater impact on a girl's life than it has on that of her male sexual partner. The well-known work of Harvard psychologist Carol Gilligan is premised on the notion that adolescence is a time of crisis for contemporary girls; so is Reviving Ophelia, a recent best-seller by clinical psychologist Mary Pipher. Gilligan's sensitive studies reveal that between the ages of eleven and sixteen young women lose their confidence and become insecure and self-doubting; Pipher sees adolescence as the time when a girl's self-esteem crumbles.10

The body is at the heart of the crisis of confidence that Gilligan, Pipher, and others describe. By age thirteen, 53 percent of American girls are unhappy with their bodies; by age seventeen, 78 percent are dissatisfied. Although there are some differences across race and class lines, talk about the body and learning how to improve it is a central motif in publications and media aimed at adolescent girls. Seventeen magazine tapped into this well of angst when it ran a headline on a story in the July 1995 issue: "Do You Hate Your Body? How to Stop." The article itself proposed ways to stop the agonizing, but the author also admitted that it was awfully hard to do so in a world where "your body is very, very important."11

Adolescent girls today face the issues girls have always faced--Who am I? Who do I want to be?--but their answers, more than ever before, revolve around the body. The increase in anorexia nervosa and bulimia in the past thirty years suggests that in some cases the body becomes an obsession, leading to recalcitrant eating behaviors that can result in death. But even among girls who never develop full-blown eating disorders, the body is so central to definitions of the self that psychologists sometimes use numerical scores of "body esteem" and "body dissatisfaction" to evaluate a girl's mental health. In the 1990s, tests that ask respondents to indicate levels of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their own thighs or buttocks have become a useful key for unlocking the inner life of many American girls.12

Why is the body still a girl's nemesis? Shouldn't today's sexually liberated girls feel better about themselves than their corseted sisters of a century ago? The historical evidence I present in this book, based on research that includes diaries written by American girls in the years between the 1830s and the 1990s, suggests that although young women today enjoy greater freedom and more options than their counterparts of a century ago, they are also under more pressure, and at greater risk, because of a unique combination of biological and cultural forces that have made the adolescent female body into a template for much of the social change of the twentieth century. I use the body as evidence to show how the mother-daughter connection has loosened, especially with regard to the experience of menstruation and sexuality; how doctors and marketers took over important educational functions that were once the special domain of female relatives and mentors; how scientific medicine, movies, and advertising created a new, more exacting ideal of physical ...

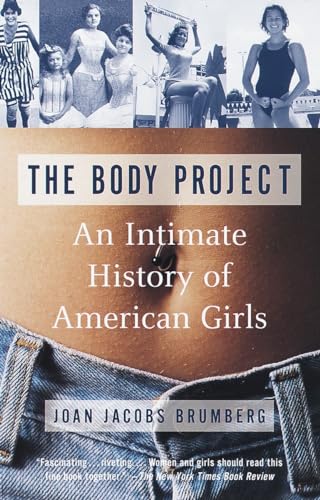

A hundred years ago, women were lacing themselves into corsets and teaching their daughters to do the same. The ideal of the day, however, was inner beauty: a focus on good deeds and a pure heart. Today American women have more social choices and personal freedom than ever before. But fifty-three percent of our girls are dissatisfied with their bodies by the age of thirteen, and many begin a pattern of weight obsession and dieting as early as eight or nine. Why?

In The Body Project, historian Joan Jacobs Brumberg answers this question, drawing on diary excerpts and media images from 1830 to the present. Tracing girls' attitudes toward topics ranging from breast size and menstruation to hair, clothing, and cosmetics, she exposes the shift from the Victorian concern with inner beauty to our modern focus on outward appearance--in particular, the desire to be model-thin and sexy. Compassionate, insightful, and gracefully written, The Body Project explores the gains and losses adolescent girls have inherited since they shed the corset and the ideal of virginity for a new world of sexual freedom and consumerism--a world in which the body is their primary project.

"Joan Brumberg's book offers us an insightful and entertaining history behind the destructive mantra of the '90s--'I hate my body!'" --Katie Couric

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurKnopf Doubleday Publishing Group

- Date d'édition1998

- ISBN 10 0679735291

- ISBN 13 9780679735298

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages336

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,97

De Canada vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

The Body Project

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : New. Paperback. Publisher overstock, may contain remainder mark on edge. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780679735298B

The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls by Brumberg, Joan Jacobs [Paperback ]

Description du livre Soft Cover. Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780679735298

Body Project : An Intimate History of American Girls

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 413021-n

The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls

Description du livre Etat : New. Book is in NEW condition. N° de réf. du vendeur 0679735291-2-1

The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls

Description du livre Etat : New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-0679735291-new

The Body Project Format: Paperback

Description du livre Etat : New. Brand New. N° de réf. du vendeur 0679735291

The Body Project (Paperback)

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Paperback. The award-winning author of Fasting Girls explores what teenage girls have lost in this new world of freedom and consumerisma world in which the body is their primary project."Fascinating . riveting . Women and girls should read this fine book together." The New York Times Book Review A hundred years ago, women were lacing themselves into corsets and teaching their daughters to do the same. The ideal of the day, however, was inner beauty: a focus on good deeds and a pure heart. Today American women have more social choices and personal freedom than ever before. But fifty-three percent of our girls are dissatisfied with their bodies by the age of thirteen, and many begin a pattern of weight obsession and dieting as early as eight or nine. Why?In The Body Project, historian Joan Jacobs Brumberg answers this question, drawing on diary excerpts and media images from 1830 to the present. Tracing girls' attitudes toward topics ranging from breast size and menstruation to hair, clothing, and cosmetics, she exposes the shift from the Victorian concern with character to our modern focus on outward appearancein particular, the desire to be model-thin and sexy. Compassionate, insightful, and gracefully written, The Body Project explores the gains and losses adolescent girls have inherited since they shed the corset and the ideal of virginity for a new world of sexual freedom and consumerisma world in which the body is their primary project. Explains how growing up female has changed over the past century and argues that American girls have come to define themselves more and more through their bodies. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780679735298

The Body Project

Description du livre Etat : New. pp. 336. N° de réf. du vendeur 26823436

The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0679735291

The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur V9780679735298