Articles liés à The Mountains Won't Remember Us: and Other Stories

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Poinsett's Bridge

Son, it was the most money I'd ever had, one ten-dollar gold piece and twenty-three silver dollars. The gold piece I put in my dinner bucket so it wouldn't get worn away by the heavy silver. The dollars clinked and weighed in my pocket like a pistol. I soon wished they was a pistol.

"What you men have done here this year will not be forgotten," Senator Pineset said before he cut the ribbon across the bridge. "The coming generations will see your work and honor you. You have opened the mountains to the world, and the world to the mountains."

And he shook hands with every one of us. I still had my dirty work clothes on, but I had washed my face and hands in the river before the ceremony. The senator was as fine a looking man as you're ever likely to see. He wore a striped silk cravat and he had the kind of slightly red face that makes you think of spirit and health.

The senator and all the other dignitaries and fine ladies got in their carriages and crossed the bridge and started up the turnpike. There was to be a banquet in Flat Rock that evening to celebrate the road and the bridge. I shook hands with the foreman, Delosier, and started up the road myself for home.

Everything seemed so quiet after the ceremony. The warm fall woods was just going on about their business, with no interest in human pomp and projects. I carried my dinner bucket and my light mason's hammer, and I thought it was time to get home and do a little squirrel hunting. I hadn't spent a weekday at home since work started on the bridge in March. Suddenly two big, rough-looking boys jumped out from behind a rock above the road and run down into the turnpike in front of me.

"Scared you?" one said, and laughed like he had told a joke.

"No,"I said.

"We'll just help you carry things up the mountain," the other said. "You got anything heavy?" He looked at my pocket bulging with the silver dollars. I had my buckeye in there too, but it didn't make any sound.

"Yeah, we'll help out," the first one said, and laughed again.

Now I had built chimneys ever since I was a boy. Back yonder people would fix up a little cabin on their own, and make a fireplace of rock, then the chimney they just built of plastered mud and sticks. Nobody had the time or skill for masonry. Way back yonder after the Indians was first gone and people moved into these hollers a wag at a time coming to grab the cheap land, they'd live in any little old shack or hole in the ground with a roof over it. The first Jones that come here they said lived in a hollow tree for a year. And I knowed other families that hid theirselves in caves and leantos below cliffs. You just did the best you could.

My grandpa fit the British at King's Mountain and at Cowpens, and then he come up here and threw together a little cabin right on the pasture hill over there. You can see the cellarhole there still. And where we lived when I was a boy the chimney would catch fire on a cold night, or if pieces of mud fell off the sticks, and we'd have to get up on the roof and pour water down. You talk about cold and wet, with the house full of smoke. That was what give Grandpa pneumonia.

That was when I promised myself to build a chimney. Nobody on the creek knew rockwork then, except to lay a rough kind of fireplace. Only masons in the county was the Germans in town, the Doxtaters and Bumgarners, the Corns, and they worked on mansions in Flat Rock, and the home of the judge, and the courthouse and such. I would have gone to learn from them but I was too scared of foreigners to go off on my own. People here was raised so far back in the woods we was afraid to go out to work. So I had to learn myself. I'd seen chimneys in Greenville when Pa and me carried to market there, and I'd marveled at the old college building north of Greenville. "Rockwork's for rich folks," Pa said, but I didn't let that stop me.

After the tops was cut and the fodder pulled one year I set myself to the job. First thing that was needed was the rocks, but they was harder to get at than it might seem at first. They was rocks in the fields and pastures. Did you just pry them up with a pole and sled them to the house? And the creek was full of rocks, but they was rounded by the water and had to be cut flat. That was the hardest work I'd ever done, believe me, getting rocks out of the creek. It was already getting cold, and I'd have to go out there in the water, find the right size, and tote them up the bank. I had to pry some loose from the mud, and scrape away the moss and slick.

They was a kind of a quarry over on the hill where the Indians must have got their flint and quartz for arrowheads. The whole slope was covered with fragments of milkquartz and I hauled in some of those to put in the fireplace where the crystals could shine in the light.

I asked Old Man Davis over at the line what could be used for mortar and he said a bucket of lime mixed with sand and water would do the trick. And even branch clay would serve, though it never set itself hard except where heated by a fire.

Took me most of the fall, way up into hog-killing time, to get my stuff assembled. I just had a hammer and one cold chisel to dress the rock. Nobody ever taught me how to cut stone, or how to measure and lay out. I just learned myself as I made mistakes and went along.

Son, I remember looking at that pile of rocks I'd carried into the yard and wondering how I'd ever put them together in a firebox and chimney. My little brother Joe had already started to play with the rocks and scatter them around. Leaves from the poplars had drifted on my heap and already it looked half-buried. I waited until Ma and Pa and the other younguns had gone over to Fletcher to Cousin Charlie's. In those times people would visit each other for a week at a time once the crops was in. I stayed home to look after the stock. One morning at daylight I lit in and tore the old mud chimney down. I knocked most of it down with an ax, it was so shackly, and then I knocked the firebox apart with a sledgehammer.

Well, there it was, the cabin with a hole in the side and winter just a few short weeks away. That was when I liked to have lost my nerve. The yard was a mess of sooty mud and sticks, and my heaps of rocks. I thought of just heading west and never coming back, of taking the horse and going. I stood there froze, you might say, with fear.

But then I seen in my pile a rock that was perfect for a cornerstone, and another that would fit against it in a line with just a little chipping. So I shoveled out and leveled the foundation and mixed up a bucket of mortar. I put the cornerstone in place, and slapped on some wet clay, then fitted the next rock to it. It was like solving a puzzle, finding rocks that would join together with just a little mud, maybe a little chipping here and there to smooth a point or corner. But best of all was the way you could rough out a line, running a string or a rule along the edge to see how it would line up, so when you backed away you saw the wall was straight in spite of gaps and bulges. I worked so hard selecting and tossing rocks for my pile, mixing more clay and water, setting stone against stone, that I never stopped for dinner. By dark I had the hole covered with the fireplace, so the coons couldn't get inside. I liked the way I made the firebox slope in toward the chimney to a place where I could put a damper. And I set between the rocks the hook Ma's pot would hang from.

It wasn't until I was milking the cow by lanternlight I seen how rough my hands had wore. The skin at the ends of my fingers and in my palms was fuzzy from handling the rock. The cow liked to kicked me, they rasped her tits so bad.

But by the time Ma and Pa had come home from Cousin Charlie's I had made them a chimney. I made my scaffold out of hickory poles and hoisted every rock up the ladder myself and set it into place. It was not the kind of chimney I'd a built later, but you can see the work over there at the old place still, kind of ragged and taking too much mortar, but still in plumb and holding together after more than sixty years. I knowed you had to go above the roof to make a chimney draw, and I got it up to maybe six inches above the comb. Later I learned any good chimney goes six feet above the ridgepole. It's the height of a chimney makes it draw, makes the flow of smoke go strong up the chimney into the cooler air. The higher she goes the harder she pulls.

People started asking me to build chimneys, and I made enough so I started using fieldstone, and breaking the rocks to get flat edges that would fit so you don't hardly have to use any mortar. They just stay together where they're laid. And people asked me to steen their wells and wall in springs and cellars. It was hard and heavy work, taking rocks out of the ground and placing them back in order, finding the new and just arrangements so they would stay. I had all the work I could do in good weather, after laying-by time.

Then I heard about the bridge old Senator Pineset was building down in South Carolina. Clara -- we was married by then -- read about it in the Greenville paper which come once a week. The senator was building a turnpike from Charleston to the mountains, to open up the Dark Corner of the state for commerce he said. But everybody knowed it was for him and his Low Country kind to bring their carriages to the cool mountains for the summer. They found out what a fine place this was and they started buying up the land around Flat Rock. But there wasn't hardly a road up Saluda Mountain and through the Gap except the little wagon trace down through Gap Creek. That's the way we hauled our hams and apples down to Greenville and Augusta in the fall. That same newspaper said the state of North Carolina was building a turnpike all the way from Tennessee to the line at Saluda Gap.

The paper said they was building this stone bridge across the North Fork of the Saluda River. It was to be fifty feet high and more than a hundred feet long,"the greatest work of masonry and engineering in upper Carolina" the paper said. And I knowed I had to work on that bridge. It was the first turnpike into the mountains and I had to go help out. The paper said they was importing masons from Philadelphia and even a master mason from England. I knowed I had to go and learn what I could.

Senator Pineset had his own ideas about the turnpike and the bridge, but we knowed there'd be thousands of cattle and hogs and sheep drove out of the mountains and across from Tennessee as well as the rich folks driving in their coaches. That highway would put us in touch with every place in the country you might want to go to.

I felt some dread, going off like that not knowing if they would hire me or not. I had no way of proving I was a mason. What would that fancy Englishman think of my laying skill? And even if the took me on it was a nine mile walk each way to the bridge site. I knowed the place all right, where the North Fork goes thorough a narrow valley too steep to get a wagon down and across.

They's something about the things a man really wants to do that scares him. He's got to go on nerve a lot of the time. And nobody else is looking or cares when you make your choices. That's the way it has to be. But it was a kind of fate, too and even Clara didn't try to stop me. She complained, as a woman will, that I'd be gone from sunup to sundown and no telling how long it would take to finish the bridge through the summer and into the fall. And she wouldn't have no help around the place except the kids. "They may not do any more hiring," she said. But I knowed better. I knowed masons and stonecutters of any kind was hard to come by in the up country, and there would be thousands of rocks to cut for such a bridge. And when I set off she give me a buckeye to put in my pocket for luck. She'd didn't normally hold to such things, but I guess she was worried as I was.

Sometimes you get a vision of what's ahead for you. And even if it's what you most want to do, you see all the work it is. It's like foreseeing an endless journey of climbing over logs and crossing creeks, looking for footholds in mud and swampland. And every little step and detail is real and has to be worked out. But it's what you are going to do, what you have been given to do. It will be your life to get through it.

That's the way I seen this work. Every one of that thousand rocks, some weighing a ton I guessed, had to be dressed, had to be measured and cut out of the mountainside, and then joined to one another. And every rock would take hundreds, maybe thousands, of hammer and chisellicks, each lick leading to another, swing by swing, chip by chip, every rock different and yet cut to fit with the rest. Every rock has its own flavor, so to speak, its own grain and hardness. No two rocks are exactly alike, but they have to be put together, supporting each other, locked into place. It was like I was behind a mountain of hammer blows, of chips and dust, and the only way out was through them. It was my life's work to get through them. And when I got through them my life would be over. It's like everybody has to earn their own death. We all want to reach the peacefulness and rest of death, but we have to work our way through a million little jobs to get there, and everybody has to do it in their own way.

The Englishman was Barnes, and he wore a top hat and silk tie, though he had a kind of apron on. "Have you been a mason long?" he said.

"Since I was a boy," I said.

"Have you ever made an arch?"

"Yes sir, over a fireplace," I said.

"Ours will be a little bigger," he said and looked me up and down.

"Let me see your hands," he said. He glanced at the calluses the trowel had made and sent me to the clerk, who he called "the clark."

I was signed on as a mason's helper, which hurt my pride some, I'll admit. All morning I thought of heading back up the trail for home, and letting the fine Englishman and crew build whatever bridge they wanted.

And if I thought about leaving when the clerk signed me on as an assistant, I thought about it twice when Barnes sent me away from the bridge site up the road to the quarry. It was about a mile where they had picked a granite face on the side of the mountain to blast away. One crew was drilling holes for the black powder, and another was put to dressing the rock that had already been blasted loose.

I had brought my light mason's hammer and trowel, but I was give a heavy hammer and some big cold chisels and told to cut a regular block, eighteen inches thick, two feet wide, and three feet long. The whole area was powdered with rock dust from the blasting and chipping.

"Surely you don't want all the blocks the same size?" I said to Delosier, the foreman from Charleston.

"The cornerstones and arch stones will be cut on the site," he said. "In the meantime we need more than five hundred regular blocks, for the body of the bridge." He showed me an architect's plan where every single block was already drawed in, separate and numbered.

"You're cutting block one aught three," he said.

Some of the men had put handkerchiefs over their noses to keep out the rock dust. They looked like a gang of outlaws hammering at the rocks, but there was nothing to protect their eyes. I squatted down to the rough block Delosier had assigned me. After the first few licks I felt even more like going home. It would take all day to cut the piece to the size Barnes required. I wasn't used to working on rocks that size and shape.

After a few more licks I saw where the smell in the quarry come from. I thought it was just burned black po...

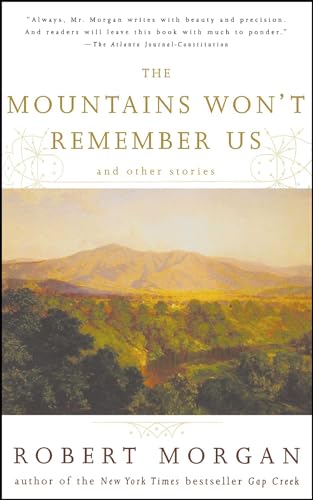

Struggling to survive in an ancient mountain landscape that alternately thwarts their efforts and infuses them with joy and vitality, the strong-limbed and strong-willed people of the Blue Ridge Mountains undergo the transition from ploughshares to bulldozers -- from the Indian skirmishes of the post-Revoluationary War era to the trailer parks of the present day. In these eleven first-person narratives, Morgan visits the themes that matter to all people in all places: birth and death, love and loss, joy and sorrow, the necessity for remembrance and the inevitability of forgetting.

This is a moving tribute to that which is universal and eternal -- the majestic immutability of the earth and the heroic human struggle to live, love, and create new life.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurTouchstone

- Date d'édition2000

- ISBN 10 0743204212

- ISBN 13 9780743204217

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages256

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

The Mountains Won't Remember Us: And Other Stories (Paperback or Softback)

Description du livre Paperback or Softback. Etat : New. The Mountains Won't Remember Us: And Other Stories 0.6. Book. N° de réf. du vendeur BBS-9780743204217

The Mountains Won't Remember Us: and Other Stories by Morgan, Robert [Paperback ]

Description du livre Soft Cover. Etat : new. This item is printed on demand. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780743204217

The Mountains Won't Remember Us: and Other Stories

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur ABLIING23Feb2416190144207

Mountains Won't Remember Us : And Other Stories

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 378908-n

The Mountains Won't Remember Us: and Other Stories

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : New. 1st Scribner Paperback Fiction e. N° de réf. du vendeur DADAX0743204212

The Mountains Won't Remember Us: and Other Stories

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : New. Brand New! This item is printed on demand. N° de réf. du vendeur 0743204212

The Mountains Won't Remember Us: and Other Stories

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : New. In shrink wrap. N° de réf. du vendeur 10-24082

The Mountains Won't Remember Us and Other Stories (Paperback)

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Paperback. From the bestselling author of Gap Creek, comes a breathtaking collection of stories about the lives and history of the settlers of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Struggling to survive in an ancient mountain landscape that alternately thwarts their efforts and infuses them with joy and vitality, the strong-limbed and strong-willed people of the Blue Ridge Mountains undergo the transition from ploughshares to bulldozers -- from the Indian skirmishes of the post-Revoluationary War era to the trailer parks of the present day. In these eleven first-person narratives, Morgan visits the themes that matter to all people in all places: birth and death, love and loss, joy and sorrow, the necessity for remembrance and the inevitability of forgetting. This is a moving tribute to that which is universal and eternal -- the majestic immutability of the earth and the heroic human struggle to live, love, and create new life. Capturing the unchanging quality of the earth and the universal human struggle to live, love, and create new life, a second collection of short fiction by the author of Gap Creek chronicles the lives of the determined, strong-willed people who settled the Blue Ridge Mountains. Reprint. 15,000 first Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780743204217

The Mountains Won't Remember Us: and Other Stories

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur I-9780743204217

The Mountains Won't Remember Us: and Other Stories

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0743204212