Articles liés à The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life's...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBN

Extrait :

Chapter One.

Seedcase

Imagine starting your life’s work at seventy-two. At just that age, Mary Granville Pendarves Delany (May 14, 1700–April 15, 1788), a fan of George Frideric Handel, a sometime dinner partner of satirist Jonathan Swift, a wearer of green-hooped satin gowns, and a fiercely devoted subject of blond King George iii, invented a precursor of what we know as collage. One afternoon in 1772 she noticed how a piece of colored paper matched the dropped petal of a geranium. After making that vital imaginative connection between paper and petal, she lifted the eighteenth-century equivalent of an X-Acto blade (she’d have called it a scalpel) or a pair of filigree-handled scissors – the kind that must have had a nose so sharp and delicate that you could almost imagine it picking up a scent. With the instrument alive in her still rather smooth-skinned hand, she began to maneuver, carefully cutting the exact geranium petal shape from the scarlet paper.

Then she snipped out another.

And another, and another, with the trance-like efficiency of repetition – commencing the most remarkable work of her life.

Her previous seventy-two years in England and Ireland had already spanned the creation of Kew Gardens, the rise of English paper making, Jacobites thrown into the Tower of London, forced marriages, women’s floral-embroidered stomachers, and the use of the flintlock musket – all of which, except for the musket, she knew very personally.

She was born Mary Granville in 1700 at her father’s country house in the Wiltshire village of Coulston, matching her life with the start of this new century, one that would be shaped by many of her friends and acquaintances. She would see the rise of the coffee house (where she took refuge on the day of the coronation of George ii) and of fabulously elaborate court gowns (one of which she designed). She would hear first-hand of the voyage of Captain Cook (financed partly by her friend the Duchess of Portland) and be astounded by that voyage’s horticultural bonanza (instigated by her acquaintance Sir Joseph Banks). She would attend her hero Handel’s Messiah. She would share a meal with the soprano Francesca Cuzzoni and read in a rapture Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novel Clarissa. She would flirt with Jonathan Swift. In middle age, at mid-century, she would see the truth of his cudgel of an essay on Irish poverty, and in her old age she would feel the sting of a revolution on the other side of the world that divided North America into Canada and the United States.

By the time she commenced her great work, she had long outlived her uncle, the selfish Lord Lansdowne (a minor poet and playwright and patron of Alexander Pope); she had survived a marriage at age seventeen to Alexander Pendarves, a drunken sixty-year-old squire who left her nothing but a widow’s pension; she had tried to get a court position and found herself in a bust-up of a relationship with the peripatetic Lord Baltimore. But with a life-saving combination of propriety and inner fire, she also designed her own clothes, took drawing lessons with Louis Goupy, cultivated stalwart, lifelong friends (and watched her mentor William Hogarth paint a portrait of one of them), played the harpsichord and attended John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, owned adorable cats, and wrote six volumes’ worth of letters – most of them to her sister, Anne Granville Dewes (1701–61), signifying a deep, cherished relationship that anyone with a sister would kill for.

She bore no children, but at forty-three she allowed herself to be kidnapped by love and to flout her family to marry Jonathan Swift’s friend Dean Patrick Delany, a Protestant Irish clergyman. They lived at Delville, an eleven-acre estate near Dublin, where Mary attended to a multitude of crafts, from shell decoration to crewelwork, and, with the Dean, renovated his lands into one of the first Picturesque gardens in the British Isles.

But she made the spectacular mental leap between what she saw and what she cut four years after he died, and eleven years after her sister died. She was staying with her insomniac friend Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, the Duchess Dowager of Portland, at the fabulous Bulstrode, an estate of many acres in Buckinghamshire. The Duchess, who would stay up being read to for most of the night and rarely rose before noon, was one of the richest women in England. Her Dutch-gabled fortress, presiding over its own park, with its own aviary, gardens, and private zoo, housed her collections of shells and minerals, and later the Portland Vase, a Roman antiquity which now occupies a spot in the British Museum. By then the two women had been friends for more than four decades. (They met when Margaret was a little girl and Mary was in her twenties. Margaret would always have been referred to by her title, except by those of us centuries later who seek to know her on a first-name basis. Mary would have called Margaret “Duchess,” and Margaret would have called Mary “Mrs.”)

Snip.

Mary Delany took the organic shapes she had cut and recomposed them in the mirror likeness of that geranium, pasting up an exact, life-sized replica of the flower on a piece of black paper.

Then the Duchess popped in.

She couldn’t tell the paper flower from the real one.

Mrs. D., which is what they affectionately call her at the British Museum, dubbed her paper and petal paste-up a flower mosaick, and in the next ten years she completed nearly a thousand cut-paper botanicals so accurate that botanists still refer to them – each one so energetically dramatic that it seems to leap out from the dark as onto a lit stage. Unlike pale botanical drawings, they are all done on deep black backgrounds. She drenched the front of white laid paper with black watercolor to obtain a stage-curtain-like darkness. Once dry, she’d paste onto these backgrounds hundreds – and I mean hundreds upon hundreds – of the tiniest dots, squiggles, scoops, moons, slivers, islands, and loops of brightly colored paper, slowly building up the verisimilitude of flora.

“I have invented a new way of imitating flowers,” she wrote with astonishing understatement to her niece in 1772.1

How did she have the eyesight to do it, let alone the physical energy? How, with her eighth-decade knuckles and wrists, did she manage the dexterity? Did her arm muscles not seize up? Now Mrs. D.’s works rustle in leather-edged volumes in the British Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings Study Room, where they have been sequestered since her descendant, Lady Llanover, donated them in 1895.

Seventy-two years old. It gives a person hope.

Who doesn’t hold out the hope of starting a memorable project at a grand old age? A life’s work is always unfinished and requires creativity till the day a person dies. Even if you’ve managed major accomplishments throughout your life and don’t really need a model for making a mark, you do need one for enriching an ongoing existence.

Where was she when she cut out her first mosaick? In the spacious ground-floor apartments that the Duchess had assigned her at Bulstrode. What time was it? Probably sometime in the morning. At night, with short candles burning (she preferred short candles because they shed more intense, lower light), it would have been time for embroidery or handiwork. Was it messy? Oh, it was messy. The Duchess was always having to clean up all their projects when she was expecting guests: her vast collection of shells and their flaking, her minerals and their dust, her exotic plants and their shedding particles of leaves.

Mrs. Delany did not pick up a quill pen, nor did she draw. Instead, she entered a mesmerized state induced by close observation. If you have ever looked at a word so long that it becomes unfamiliar, you have crossed into a similar state, seizing on detail, then seizing up, because that very focus blurs the context of meaning. This is the mental ambience in which a ghost of something can appear. A memory. An atmosphere of a time in life long gone but now present and almost palpable to the touch. Touch is the operative word here because Mary Delany touched many implements. According to those who’ve tried to recreate her technique, Mrs. Delany used tweezers, a bodkin (an embroidery tool for poking holes), perhaps a thin, flat bone folder (shaped like a tongue depressor and made for creasing paper), brushes of various kinds, mortar and pestle for grinding pigment, bowls to contain ox gall (the bile of cows which when mixed with paint made it flow more smoothly) and more bowls to contain the honey that would plasticize the pigment for her inky backgrounds, pieces of glass or board to fix her papers, pins to hang her papers to dry.2 It was a feast for the tactile sense; it was dirty, smelly, prodigious.

If you make an appointment to see the flower mosaicks in the Prints and Drawings Study Room of the British Museum, they will let you hold these miracles by the edges of their mats (provided you borrow a pair of chalky curatorial gloves) or even let you turn the pages of their albums. I dare you not to release a dumbfounded syllable or two out of sheer disbelief and disturb the whole staid mahogany room. The flowers are portraits of the possibilities of age. They are aged. They can be portraits of sexual intensity – but softened. Softer, and drier, as our sexuality becomes. Yet they also can be simple botany, nearly accurate representations of specimens. They all come out of darkness, intense and vaginal, bright on their black backgrounds as if, had she possessed one, she had shined a flashlight on nine hundred and eighty-five flowers’ cunts.

Flow...

Présentation de l'éditeur :

Seedcase

Imagine starting your life’s work at seventy-two. At just that age, Mary Granville Pendarves Delany (May 14, 1700–April 15, 1788), a fan of George Frideric Handel, a sometime dinner partner of satirist Jonathan Swift, a wearer of green-hooped satin gowns, and a fiercely devoted subject of blond King George iii, invented a precursor of what we know as collage. One afternoon in 1772 she noticed how a piece of colored paper matched the dropped petal of a geranium. After making that vital imaginative connection between paper and petal, she lifted the eighteenth-century equivalent of an X-Acto blade (she’d have called it a scalpel) or a pair of filigree-handled scissors – the kind that must have had a nose so sharp and delicate that you could almost imagine it picking up a scent. With the instrument alive in her still rather smooth-skinned hand, she began to maneuver, carefully cutting the exact geranium petal shape from the scarlet paper.

Then she snipped out another.

And another, and another, with the trance-like efficiency of repetition – commencing the most remarkable work of her life.

Her previous seventy-two years in England and Ireland had already spanned the creation of Kew Gardens, the rise of English paper making, Jacobites thrown into the Tower of London, forced marriages, women’s floral-embroidered stomachers, and the use of the flintlock musket – all of which, except for the musket, she knew very personally.

She was born Mary Granville in 1700 at her father’s country house in the Wiltshire village of Coulston, matching her life with the start of this new century, one that would be shaped by many of her friends and acquaintances. She would see the rise of the coffee house (where she took refuge on the day of the coronation of George ii) and of fabulously elaborate court gowns (one of which she designed). She would hear first-hand of the voyage of Captain Cook (financed partly by her friend the Duchess of Portland) and be astounded by that voyage’s horticultural bonanza (instigated by her acquaintance Sir Joseph Banks). She would attend her hero Handel’s Messiah. She would share a meal with the soprano Francesca Cuzzoni and read in a rapture Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novel Clarissa. She would flirt with Jonathan Swift. In middle age, at mid-century, she would see the truth of his cudgel of an essay on Irish poverty, and in her old age she would feel the sting of a revolution on the other side of the world that divided North America into Canada and the United States.

By the time she commenced her great work, she had long outlived her uncle, the selfish Lord Lansdowne (a minor poet and playwright and patron of Alexander Pope); she had survived a marriage at age seventeen to Alexander Pendarves, a drunken sixty-year-old squire who left her nothing but a widow’s pension; she had tried to get a court position and found herself in a bust-up of a relationship with the peripatetic Lord Baltimore. But with a life-saving combination of propriety and inner fire, she also designed her own clothes, took drawing lessons with Louis Goupy, cultivated stalwart, lifelong friends (and watched her mentor William Hogarth paint a portrait of one of them), played the harpsichord and attended John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, owned adorable cats, and wrote six volumes’ worth of letters – most of them to her sister, Anne Granville Dewes (1701–61), signifying a deep, cherished relationship that anyone with a sister would kill for.

She bore no children, but at forty-three she allowed herself to be kidnapped by love and to flout her family to marry Jonathan Swift’s friend Dean Patrick Delany, a Protestant Irish clergyman. They lived at Delville, an eleven-acre estate near Dublin, where Mary attended to a multitude of crafts, from shell decoration to crewelwork, and, with the Dean, renovated his lands into one of the first Picturesque gardens in the British Isles.

But she made the spectacular mental leap between what she saw and what she cut four years after he died, and eleven years after her sister died. She was staying with her insomniac friend Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, the Duchess Dowager of Portland, at the fabulous Bulstrode, an estate of many acres in Buckinghamshire. The Duchess, who would stay up being read to for most of the night and rarely rose before noon, was one of the richest women in England. Her Dutch-gabled fortress, presiding over its own park, with its own aviary, gardens, and private zoo, housed her collections of shells and minerals, and later the Portland Vase, a Roman antiquity which now occupies a spot in the British Museum. By then the two women had been friends for more than four decades. (They met when Margaret was a little girl and Mary was in her twenties. Margaret would always have been referred to by her title, except by those of us centuries later who seek to know her on a first-name basis. Mary would have called Margaret “Duchess,” and Margaret would have called Mary “Mrs.”)

Snip.

Mary Delany took the organic shapes she had cut and recomposed them in the mirror likeness of that geranium, pasting up an exact, life-sized replica of the flower on a piece of black paper.

Then the Duchess popped in.

She couldn’t tell the paper flower from the real one.

Mrs. D., which is what they affectionately call her at the British Museum, dubbed her paper and petal paste-up a flower mosaick, and in the next ten years she completed nearly a thousand cut-paper botanicals so accurate that botanists still refer to them – each one so energetically dramatic that it seems to leap out from the dark as onto a lit stage. Unlike pale botanical drawings, they are all done on deep black backgrounds. She drenched the front of white laid paper with black watercolor to obtain a stage-curtain-like darkness. Once dry, she’d paste onto these backgrounds hundreds – and I mean hundreds upon hundreds – of the tiniest dots, squiggles, scoops, moons, slivers, islands, and loops of brightly colored paper, slowly building up the verisimilitude of flora.

“I have invented a new way of imitating flowers,” she wrote with astonishing understatement to her niece in 1772.1

How did she have the eyesight to do it, let alone the physical energy? How, with her eighth-decade knuckles and wrists, did she manage the dexterity? Did her arm muscles not seize up? Now Mrs. D.’s works rustle in leather-edged volumes in the British Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings Study Room, where they have been sequestered since her descendant, Lady Llanover, donated them in 1895.

Seventy-two years old. It gives a person hope.

Who doesn’t hold out the hope of starting a memorable project at a grand old age? A life’s work is always unfinished and requires creativity till the day a person dies. Even if you’ve managed major accomplishments throughout your life and don’t really need a model for making a mark, you do need one for enriching an ongoing existence.

Where was she when she cut out her first mosaick? In the spacious ground-floor apartments that the Duchess had assigned her at Bulstrode. What time was it? Probably sometime in the morning. At night, with short candles burning (she preferred short candles because they shed more intense, lower light), it would have been time for embroidery or handiwork. Was it messy? Oh, it was messy. The Duchess was always having to clean up all their projects when she was expecting guests: her vast collection of shells and their flaking, her minerals and their dust, her exotic plants and their shedding particles of leaves.

Mrs. Delany did not pick up a quill pen, nor did she draw. Instead, she entered a mesmerized state induced by close observation. If you have ever looked at a word so long that it becomes unfamiliar, you have crossed into a similar state, seizing on detail, then seizing up, because that very focus blurs the context of meaning. This is the mental ambience in which a ghost of something can appear. A memory. An atmosphere of a time in life long gone but now present and almost palpable to the touch. Touch is the operative word here because Mary Delany touched many implements. According to those who’ve tried to recreate her technique, Mrs. Delany used tweezers, a bodkin (an embroidery tool for poking holes), perhaps a thin, flat bone folder (shaped like a tongue depressor and made for creasing paper), brushes of various kinds, mortar and pestle for grinding pigment, bowls to contain ox gall (the bile of cows which when mixed with paint made it flow more smoothly) and more bowls to contain the honey that would plasticize the pigment for her inky backgrounds, pieces of glass or board to fix her papers, pins to hang her papers to dry.2 It was a feast for the tactile sense; it was dirty, smelly, prodigious.

If you make an appointment to see the flower mosaicks in the Prints and Drawings Study Room of the British Museum, they will let you hold these miracles by the edges of their mats (provided you borrow a pair of chalky curatorial gloves) or even let you turn the pages of their albums. I dare you not to release a dumbfounded syllable or two out of sheer disbelief and disturb the whole staid mahogany room. The flowers are portraits of the possibilities of age. They are aged. They can be portraits of sexual intensity – but softened. Softer, and drier, as our sexuality becomes. Yet they also can be simple botany, nearly accurate representations of specimens. They all come out of darkness, intense and vaginal, bright on their black backgrounds as if, had she possessed one, she had shined a flashlight on nine hundred and eighty-five flowers’ cunts.

Flow...

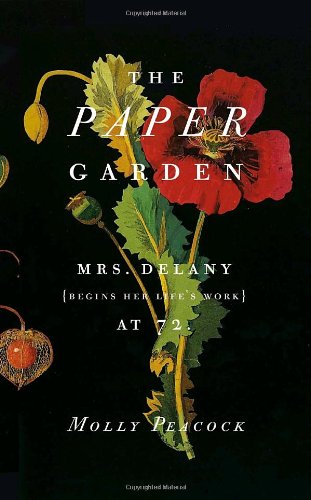

The Paper Garden is unlike anything else you have ever read. At once a biography of an extraordinary 18th century gentlewoman and a meditation on late-life creativity, it is a beautifully written tour de force from an acclaimed poet. Mary Granville Pendarves Delany (1700-1788) was the witty, beautiful and talented daughter of a minor branch of a powerful family. Married off at 16 to a 61-year-old drunken squire to improve the family fortunes, she was widowed by 25, and henceforth had a small stipend and a horror of a marriage. She spurned many suitors over the next twenty years, including the powerful Lord Baltimore and the charismatic radical John Wesley. She cultivated a wide circle of friends, including Handel and Jonathan Swift. And she painted, she stitched, she observed, as she swirled in the outskirts of the Georgian court. In mid-life she found love, and married. Upon her husband's death 23 years later, she arose from her grief, picked up a pair of scissors and, at the age of 72, created a new art form, mixed-media collage. Over the next decade, Mrs Delany created an astonishing 985 botanically correct, breathtaking cut-paper flowers, now housed in the British Museum and referred to as the Botanica Delanica.

Delicately, Peacock has woven parallels in her own life around the story of Mrs Delany's and, in doing so, has made this biography into a profound and beautiful examination of the nature of creativity and art.

Gorgeously designed and featuring 35 full-colour illustrations, this is a sumptuous and lively book full of fashion and friendships, gossip and politics, letters and love. It's to be devoured as voraciously as one of the court dinners it describes.

Delicately, Peacock has woven parallels in her own life around the story of Mrs Delany's and, in doing so, has made this biography into a profound and beautiful examination of the nature of creativity and art.

Gorgeously designed and featuring 35 full-colour illustrations, this is a sumptuous and lively book full of fashion and friendships, gossip and politics, letters and love. It's to be devoured as voraciously as one of the court dinners it describes.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ISBN 10 0771070330

- ISBN 13 9780771070334

- ReliureRelié

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 162,04

Frais de port :

EUR 4,03

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life's Work at 72

Edité par

McClelland & Stewart

(2010)

ISBN 10 : 0771070330

ISBN 13 : 9780771070334

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover0771070330

Acheter neuf

EUR 162,04

Autre devise

The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life's Work at 72

Edité par

McClelland & Stewart

(2010)

ISBN 10 : 0771070330

ISBN 13 : 9780771070334

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0771070330

Acheter neuf

EUR 162,62

Autre devise

The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life's Work at 72

Edité par

McClelland & Stewart

(2010)

ISBN 10 : 0771070330

ISBN 13 : 9780771070334

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 2

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Brand New!. N° de réf. du vendeur VIB0771070330

Acheter neuf

EUR 176,22

Autre devise