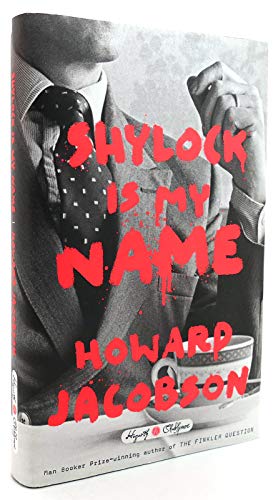

Articles liés à Shylock Is My Name: The Merchant of Venice Retold

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNCopyright ©2016 Howard Jacobsen

It is one of those better-to-be-dead-than-alive days you get in the North of England in February, the space between the land and sky a mere letterbox of squeezed light, the sky itself unfathomably banal. A stage unsuited to tragedy, even here where the dead lie quietly. There are two men in the cemetery, occupied in duties of the heart. They don't look up. In these parts you must wage war against the weather if you don't want farce to claim you.

Signs of just such a struggle are etched on the face of the first of the mourners, a man of middle-age and uncertain bearing, who sometimes walks with his head held arrogantly high, and at others stoops as though hoping not to be seen. His mouth, too, is twitchy and misleading, his lips one moment twisted into a sneer, the next fallen softly open, as vulnerable to bruising as summer fruit. He is Simon Strulovitch - a rich, furious, but easily hurt philanthropist with on-again off-again enthusiasms, a distinguished collection of twentieth-century Anglo-Jewish art and old Bibles, a passion for Shakespeare (whose genius and swashbuckling Sephardi looks he once thought could only be explained by the playwright's ancestors having changed their name from Shapiro, but now he isn't sure), honorary doctorates from universities in London, Manchester and Tel Aviv (the one from Tel Aviv is something else he isn't sure about) and a daughter going off the rails. He is here to inspect the stone that has recently been erected at the head of his mother's grave, now that the 12 months of mourning for her has elapsed. He hasn't mourned her conscientiously during that period - too busy buying and lending art, too busy with his foundations and endowments, or 'benefacting,' as his mother called it with mixture of pride and concern (she didn't want him killing himself giving money away), too busy settling scores in his head, too busy with his daughter - but he intends to make amends. There is always time to be a better son.

Or a better father. Could it be that it's his daughter he's really getting ready to mourn? These things run in families. His father had briefly mourned him. 'You are dead to me!' And why? Because of his bride's religion. Yet his father wasn't in the slightest bit religious.

'Better you were dead at my feet...'

Would that really have been better?

We can't get enough of dying, he thinks, shuffling between the unheralded headstones. 'We' - an idea of belonging to which he sometimes subscribes and sometimes doesn't. We arrive, lucky to be alive, carrying our belongings on a stick, and immediately look for somewhere to bury the children who betray us.

Perhaps because of all the anger that precedes all the burying, the place lacks the consolation of beauty. In his student days, when there was no word 'we' in his vocabulary, Strulovitch wrote a paper on Stanley Spencer's 'The Resurrection, Cookham', admiring the tumult of Spencer's graves, bulging with eager life, the dead in a hurry for what comes next. But this isn't a country churchyard in Berkshire; this is a cemetery of the Messiahless in Gatley, South Manchester, where there is no next. It all finishes here.

There is a lingering of snow on the ground, turning a dirty black where it nestles into the granite of the graves. It will be there until early summer, if summer ever comes.

The second person, here long before Strulovitch arrived, tenderly addressing the occupant of a grave whose headstone is worn to nothing, is Shylock, also an infuriated and tempestuous Jew, though his fury tends more to the sardonic than the mercurial, and the tempest subsides when he is able to enjoy the company of his wife Leah, buried deep beneath the snow. He is less divided in himself than Strulovitch but, perhaps for that very reason, more divisive. No two people feel the same about him. Even those who unreservedly despise him, despise him with different degrees of unreservation. He has money worries that Strulovitch doesn't, collects neither art nor Bibles, and finds it difficult to be charitable where people are not charitable to him, which some would say takes something from the soul of charity. About his daughter, the least said the better.

He is not an occasional mourner like Strulovitch. He cannot leave and think of something else. Because he is not a forgetful or a forgiving man, there never was or will be something else.

Strulovitch, pausing in his reflections, feels Shylock's presence before he sees him - a blow to the back of the neck, as though someone in the cemetery has been irreverent enough to throw a snowball.

The words 'My dearest Leah,' dropped like blessings into the icy grave, reach Strulovitch's ears. There will be many Leahs here. Strulovitch's mother was a Leah. But this Leah attracts an imperishable piteousness to her name that is unmistakable to Strulovitch, student of husbandly sorrow and fatherly wrath. Leah who bought Shylock a courtship ring. Leah, mother to Jessica who stole that ring to buy a monkey. Jessica the pattern of perfidy. Not for a wilderness of monkeys would Shylock have parted with that ring.

Strulovitch neither.

So 'we' does mean something to Strulovitch after all. The faith Jessica violates is his faith.

Such, anyway, are the only clues to recognition Strulovitch needs. He is matter of fact about it. Of course Shylock is here, among the dead. When hasn't he been?

Eleven years old, precociously moustached, too clever by half, he was shopping with his mother in a department store when she saw Hitler buying aftershave.

'Quick, Simon!' she ordered him. 'Run and get a policeman, I'll stay here and make sure he doesn't get away.'

But no policeman would believe that Hitler was in the store and eventually he escaped Strulovitch's mother's scrutiny.

Strulovitch hadn't believed that Hitler was in the store either. Back home he made a joke of it to his father.

'Don't cheek your mother,' his father told him. 'If she said she saw Hitler, she saw Hitler. Your Aunty Annie ran into Stalin on Stockport market last year, and when I was your age I saw Moses rowing on Heaton Park Lake.'

'Couldn't have been,' Strulovitch said. 'Moses would just have parted the waters.'

For which smart remark he was sent to his room.

'Unless it was Noah,' Strulovitch shouted from the top of the stairs.

'And for that,' his father said, 'you're not getting anything to eat.'

Later, his mother sneaked a sandwich up to him, as Rebekah would have done for Jacob.

The older Strulovitch understands the Jewish imagination better - why it sets no limits to chronology or topography, why it cannot ever trust the past to the past, and why his mother probably did see Hitler. He is no Talmudist but he occasionally reads a page in a small, private-press anthology of the best bits. The thing about the Talmud is that it allows a bolshie contrarian like him to argue face-to-face with other bolshie contrarians long dead.

You think what, Rabbah bar Nahmani? Well fuck you!

So is there a hereafter after all? What's your view, Rabbi?

To Strulovitch, Rabbah bar Nahmani, shaking off his cerements, gives the finger back.

Long ago is now and somewhere else is here.

How it is that Leah should be buried among the dead of Gatley is a question only a fool would risk Shylock's displeasure by asking. The specifics of interment - the whens, the wheres - are supremely unimportant to him. She is under the ground, that is enough. Alive, she had been everywhere to him. Dead - he long ago determined - she will be the same. Wheeling with the planet. An eternal presence, never far from him, wherever he treads.

Strulovitch, alert and avid, tensed like a minor instrument into affinity with a greater, watches without being seen to watch. He will stand here all day if he has to. From Shylock's demeanour - the way he inclines his head, nods, looks away, but never looks at anything, sees sideways like a snake - he is able to deduce that the conversation with Leah is engrossing and devoted, oblivious to external event, and no longer painful - a fond but brisk, even matter-of-fact, two-way affair. Shylock listens as much as he speaks, pondering the things she says, though he must have heard her say them many times before. He has a paperback in one hand, rolled up like a legal document or a gangster's wad of bank notes, and every now and then he opens it brusquely, as though he intends to rip out a page, and reads to her in a low voice, covering his mouth in the way a person who is too private to make a show of mirth

will stifle a laugh. If that is laughter, Strulovitch thinks, it's laughter that has had a long way to travel - brain laughter. A phrase of Kafka's (what's one more unhappy son in this battlefield of them?) returns to him: laughter that has no lungs behind it. Like Kafka's own, maybe. Mine too? - Strulovitch wonders. Laughter that lies too deep for lungs? As for the jokes, if they are jokes, they are strictly private. Just possibly, unseemly.

He is is at home here as I am not, Strulovitch thinks. At home among the gravestones. At home in a marriage.

Strulovitch is pierced by the difference between Shylock's situation and his. His own marital record is poor. He and his first wife made a little hell of their life together. Was that because she'd been a Christian? ('Gai in drerd!' his father said when he learnt his son was marrying out. 'Go to hell!' Not just any hell but the fieriest circle, where marriers-out go. And on the night before the wedding he left an even less ambiguous phone message: 'You are dead to me.') His second marriage, to a daughter of Abraham this time, for which reason his father rescinded his curse and called him Lazarus on the phone, was brought to an abrupt, numbing halt - a suspension of all feeling, akin to waiting for news you hope will never come - when his wife suffered a stroke on their daughter's fourteenth birthday, losing the better part of language and memory, and when he, as a consequence, shut down the husband part of his heart.

Marriage! You lose your father or you lose your wife.

He is no stranger to self-pity. Leah is more alive to Shylock than poor Kay is to me, he thinks, feeling the cold for the first time that day.

He notes, observing Shylock, that there is a muscular tightness in his back and neck. This calls to mind a character in one of his favourite comics of years ago, a boxer, or was he a wrestler, who was always drawn with wavy lines around him, to suggest a force field. How would I be drawn, Strulovitch wonders. What marks could denote what I'm feeling?

'Imagine that,' Shylock says to Leah.

'Imagine what, my love?'

'Shylock-envy.'

Such a lovely laugh she has.

Shylock is dressed in a long black coat, the hem of which he appears concerned to keep out of the snow, and sits, inclined forward - but not so far as to crease his coat - on a folding stool of the kind Home Counties opera-lovers take to Glyndebourne. Strulovitch cannot decide what statement his hat is making. Were he to have asked, Shylock would have told him it was to keep his head warm. But it's a fedora - the mark of a man conscious of his appearance. A dandy's hat, worn with a hint of frolicsome menace belied by the absence of any mark or memory of frolic on his face.

Strulovitch's clothes are the more abstemious, his art-collector's coat flowing like a surplice, the collar of his snowy white shirt buttoned to the throat without a tie in the style of contemporary quattrocento. Shylock, with his air of dangerous inaffability, is less ethereal and could be taken for a banker or a lawyer. Just possibly he could be a Godfather.

Strulovitch is glad he came to pay his respects to his mother's remains and wonders whether the graveside conversation he is witness to is his reward. Is this what you get for being a good son? He should have tried it sooner in that case. Unless something else explains it. Does one simply see what one is fit to see? In which case there's no point going looking: you have to let it come to you. He entertains a passing fancy that Shakespeare, whose ancestors just might - to be on the safe side - have changed their name from Shapiro, also allowed Shylock to come to him. Walking home from the theatre, seeing ghosts and writing in his tablets, he looks outside himself just long enough to espy Antonio spitting at that abominated thing, a Jew.

'How now! A Jew! Is that you cousin?' Shakespeare asks.

This is Juden-frei Elizabethan England. Hence his surprise.

'Shush,' says the Jew.

'Shylock!' exclaims Shakespeare, heedlessly. 'My cousin Shylock or I'm a

Christian!'

Shapiro, Shakespeare, Shylock. A family association.

Strulovitch feels sad to be excluded. Only a shame his name doesn't have a

shush in it.

It is evident to Strulovitch, anyway, that receptivity is the thing, and that those who go looking are on a fool's errand. He knows of a picturesque Jewish cemetery on the Lido di Venezia - once abandoned but latterly restored in line with the new European spirit of reparation - a cypress-guarded place of melancholy gloom and sudden shafts of cruel light, to which a fevered righter of wrongs of his acquaintance has made countless pilgrimages, certain that since Shylock would not have been seen dead among the ice-cream licking tourists in the Venice ghetto, he must find him here, broken and embittered, gliding between the ruined tombstones, muttering the prayer for his several dead. But no luck. The great German poet Heine - a man every bit as unwilling to use the 'we' word as Strulovitch, and the next day every bit as much in love with it - went on an identically sentimental 'dream-hunt', again without success.

But the hunting - with so much unresolved and still to be redeemed - never stops. Simon Strulovitch's trembling Jew-mad Christian wife, Ophelia-Jane, pointed him out, hobbling down the Rialto steps, carrying a fake Louis Vuitton bag stuffed with fake Dunhill watches, as they were dining by the Grand Canal. They were on their honeymoon and Ophelia-Jane wanted to do something Jewishly nice for her new husband. (He hadn't told her that his father had verbally buried him on the eve of their wedding. He would never tell her that.) 'Look, Si!' she'd said, tugging his sleeve. A gesture that annoyed him because of the care he lavished on his clothes. Which might have been why he took an eternity following the direction of her finger and when at last he looked saw nothing.

It was in the hope of a second visitation that she took him there on every remaining night of their honeymoon. 'Oy gevalto, we're back on the Rialto,' he complained finally. She put her face in her hands. She thought him ungrateful and unserious. Five days into their marriage she already hated his folksy yiddishisms. They took from the grandeur she wanted for them both. Venice had been her idea. Reconnect him. She could just as easily have suggested Cordoba. She had married him to get close to the tragic experience of the Hebrews, the tribulations ...

“[An] ebullient riff on Shakespeare... [a] blend of purposeful deja vu and Jewish fatalism...Jacobson’s highflying wit is more Stoppardian than Shakespearean, even amid rom-com subplots and phallocentric jests equally well suited to Elizabethan drama as to the world of Judd Apatow.”

-- The New York Times Book Review

“Jacobson... has delivered with authority and style... [a] deft artist firmly in control, offering witty twists to a play long experienced by many as a racial tragedy.”

-– The Washington Post

“Sharply written, profoundly provocative.”

--The Huffington Post

"The Shylock of the novel is ... a character in search of an author, or at least an author who will write him fully, fill in the blanks and give him a voice where once he was voiceless. And in Jacobson, after just over 400 years, he has found a mensch who has done—with considerable skill—exactly that."

-- The Daily Beast

“Stimulating... Jacobson is ideally suited to take on ‘Merchant.’”

-- The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“It is delicious...Jacobson is one of our finest writers.”

-- Forward

“A funny and insightful reimagining of The Merchant of Venice...Jacobson is uniquely qualified to take on The Merchant of Venice.”

-- The Miami Herald

“A serious comic masterpiece.”

–- The Spectator (UK)

“Supremely stylish, probing and unsettling...This Shylock is a sympathetic character... both savagely funny and intellectually searching, both wise and sophistical, intimate and coldly controlling... Jacobson's writing is virtuoso. He is a master of shifting tones, from the satirical to the serious. His prose has the sort of elastic precision you only get from a writer who is truly in command.”

-- The Independent (UK)

“Jacobson takes the play's themes - justice, revenge, mercy, Jews and Christians, Jew-hatred, fathers and daughters - and works away at them with dark humour and rare intelligence... This is Jacobson at his best. There is no funnier writer in English today. Not just laugh-out-loud humour, though there is plenty of that, including wonderful jokes about circumcision and masturbation. But a sharp, biting humour, which stabs home in a single line... This is one of his best novels yet.”

– Jewish Chronicle (UK)

“Part remake, part satire and part symposium, Jacobson's Merchant is less Shakespeare retold than Shakespeare reverse-engineered... in these juicy, intemperate, wisecracking squabbles, Jacobson really communicates with Shakespeare's play, teasing out the lacunae, quietly adjusting its emphases ... and making startlingly creative use of the centuries-old playscript.”

–-Daily Telegraph (UK)

“Jacobson, with glorious chutzpah, gives Shylock his Act V, and the end when it comes is extremely satisfying... Provocative, caustic and bold.”

–- Financial Times (UK)

"Jacobson is a novelist of ideas... What is added to a great work in the rewriting? Do we need the argot of the 21st century because the original is now intimidatingly remote? [Shylock Is My Name] is a moving, disturbing and compelling riposte to the blithe resolution offered in the urtext."

-- Sydney Morning Herald (Australia)

“Jacobson treats Shylock less as a product of Shakespeare’s culture and imagination than as a real historical figure emblematic of Jewish experience—an approach that gives the novel peculiar vigour.”

– Prospect Magazine (UK)

“When Shylock and Strulovitch are swapping jokes, stories, and fears, the tale is energetic...a work that stands on its own.”

– Publishers Weekly

“The Merchant is well-suited to Jacobson, a Philip Roth–like British writer known for his sterling prose and Jewish themes....full of the facile asides and riffs for which Jacobson has been praised.” -- Kirkus

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurHogarth Pr

- Date d'édition2016

- ISBN 10 0804141320

- ISBN 13 9780804141321

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages275

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,75

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Shylock Is My Name (Hogarth Shakespeare)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0804141320

Shylock Is My Name (Hogarth Shakespeare)

Description du livre Etat : New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. N° de réf. du vendeur bk0804141320xvz189zvxnew

Shylock Is My Name (Hogarth Shakespeare)

Description du livre Etat : New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-0804141320-new

Shylock Is My Name (Hogarth Shakespeare)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0804141320

Shylock Is My Name (Hogarth Shakespeare)

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover0804141320

Shylock Is My Name (Hogarth Shakespeare)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0804141320