Articles liés à Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

I will always remember the day Emmett was born. It was July 25, 1941. A Friday. But I’m getting a little ahead of my story, because this is not where it really begins. You see, my mother had brought me to the hospital on Wednesday. And the fact that it was my mother and not my husband who took me to the hospital to have a baby probably tells you just about everything you need to know about Louis Till. He was at work that day, I think. He worked at the Corn Products Refining Company in Argo, Illinois, where we lived, just outside Chicago. I guess you might call Argo a suburb, but it didn’t have anything at all in common with the big city, except for being close to it. It was a sleepy little town where whites called blacks by their first names and where blacks would never dare do the same thing. It was a place where most little black girls dropped out of school by age sixteen to get married and where I was considered an old maid because I had waited until I finished high school to marry Louis at age eighteen. That was just the year before. Argo was also a place where it seemed the greatest ambition of most black men, like my father and my husband, was to work for Corn Products, and the greatest ambition of their wives was to take care of things at home for their husbands. So it was with my mother, who did what my mother always seemed to be there to do. She took care of me, and on that Wednesday when she drove me to Cook County Hospital in Chicago, I really needed care. I was going into labor and I didn’t understand much about that except for this: those pains were talking to me. They were saying: "Any minute now, Mamie Till. Any minute, girl."

Now, Cook County was a public hospital and it was one place you were sure black folks could get treated. That’s not to say that we were treated well. The nurses decided right away that this was not an emergency. But, then, of course, they were feeling no pain. They put me into a room with another lady and it seems that I was the only one who noticed that this woman was screaming and hollering and cursing and she was going through every four-letter word she could think of, teaching me a few in the process. That was about the time my pain stopped. I felt so sorry for her that I forgot my own troubles. I got up out of my bed after everyone left and started trying to comfort her, help ease her pain. I didn’t understand a lot of things back then. I mean, I was so naive it wasn’t safe for me to walk the streets alone. And listening to the screams of that poor woman really frightened me because I didn’t understand any of it. My God, was this what was in store for me? No one had prepared me for any of this. Why hadn’t my mother talked to me about these things? And why on earth did this woman want to kill her husband? I guess it was her husband. "That man," I think is what she kept saying. Anyway, she told me that I would soon find out why.

Over the next couple of days, I was in and out of pain–terrible pain–and my mother was in and out of the room checking on things, taking care of me. That room always seemed dark, like a government office, not cheerful the way I thought it should look for such a blessed event. But that was Cook County Hospital. Louis never came to see about me. I would have thought that he would be excited about the baby, but he didn’t seem to care. On Friday during one of my mother’s visits, I told her what I had been telling the nurses: that I needed to go, that if the pain was a sign, then it was definitely time. I didn’t think I could take another minute of it. But they weren’t paying me any attention. Mama asked if my water had broken. I told her I thought it had and that I had asked somebody to come and change my bed. But when they didn’t, I just pulled the blanket up and got back on top of the bed. Well, Alma Gaines was having none of that. My mother called the nurse, who checked my situation and quickly got me into the labor room. And that’s where things really got serious. The doctor there began to examine me. He said something that I didn’t get, but I could hear the urgency in his voice. What I understood was that they had to get busy. They had to take my baby. The baby was coming butt first. It was a breech birth. I had no idea how serious that could be, but even I understood the anxiety I heard in the doctor’s voice, and the tense way things were moving in that room.

"What have you been doing?" he asked, like he was accusing me of murder.

Now I knew; it was my fault. Whatever was happening to my baby was all my fault. The only thing I could recall was that Louis and I had moved into a new place not that long before all of this. As the medical team rushed to prep me, I thought about that move from my mother’s house to a little apartment down the street. I was so proud of that little place, our first apartment. I had bought curtains. Everything had to be perfect. I mean, I was such a perfectionist. And now, of course, I know better, but I didn’t know anything then. I was hanging curtains and I was cleaning cobwebs high up on the windows. And somebody came by and saw me and told me I shouldn’t reach overhead like that. So, it was my fault that all this was happening, all because I wanted a nice, clean place for the baby to live and play. Now, in the delivery room, I was being punished for it, but I didn’t want my baby to have to suffer for my mistake. The agony was so severe, I finally understood why that woman back in the room wanted to kill "that man." Somehow, though, I didn’t think that would help. At that moment, I thought there could be no greater pain than giving birth to a child. I couldn’t imagine then how much more pain a mother might have to endure. Someone placed a cone over my mouth and told me to count backward from one hundred. The last thing I remember was ". . . ninety-nine . . ."

When I finally awakened, it seemed as if I had been dreaming. I was back in the room, but there was no baby there. In fact, I had never even seen my baby. I wanted to know where they had taken the baby. All they told me was that I was very sick, and they really didn’t want to bring him to me and they had taken him to do whatever it is they do to babies. "Him." A boy. I kept insisting on seeing my baby boy and, finally, they gave in and brought him to me, probably just to keep me quiet, knowing how mothers are. But I didn’t care. I was so happy to see my baby, all six and three-quarters pounds of him.

Happy, that is, until I looked down at him in my arms.

I reacted right away with a frown. "Oooh, no . . ."I said, before thinking much about it.

His skin color was very, very light and he had blond hair and blue eyes. I looked up at the nurse, but I was assured that they had handed me the right baby. There was more. It had been such a difficult birth that they had used forceps and clinched him at the temples. He was scarred on his forehead and on the nose, and his little face looked distorted. My reaction must have startled him. His eyes grew wide, and he began to cry.

I pulled him closer to my bosom and rocked him gently. "Oh, honey. Mama loves you."

That was our first connection, mother and son. I was so contrite after that and I would remember all of my life how my son looked when he came into the world, and how I reacted to it.

The attending nurse needed a name to complete the birth certificate form. I had been ready for some time. Now, this was long before you could tell what sex a baby was going to be ahead of time, the way people do these days. But I just knew I would have a boy. After all, I had decided, a boy first, then a girl, then another boy and then another girl. So, weeks before I went to the hospital, I asked my husband what he wanted to name our son. He just shrugged and sort of brushed me off. Then I thought about my favorite uncle, who didn’t seem much concerned, either, when I asked him. That’s when I decided myself on the name Emmett Louis, after my favorite uncle and my husband, because they didn’t care and I did.

We didn’t have long together during that first visit. Emmett was taken from me again right away. I was running a temperature and at a certain point, I think I became delirious. It’s all a blur. They had given me eighteen stitches inside and I don’t know how many outside. But I began scratching at the stitches and, in my state of mind, I guess I was causing problems, making things worse. Infection set in and I had to be looked after. Emmett was in even worse shape. His neck, right knee, and left wrist had been constricted by the umbilical cord. He could have choked to death. Thank God, he didn’t. His wrist was swollen and his knee was swollen even more. It was as big as an apple. The circulation had been cut off. Apparently, that was what kept him from being delivered normally, what caused the breech birth and what forced the doctors to use the forceps to help him into the world. And it was why that doctor seemed to be accusing me of being a bad mother even before I became a mother; all because I hadn’t been taught how to prepare for such an important part of my life.

There are certain things that a parent owes a child. One is to prepare him for the world outside. I know this, not only because I became a mother, but because I learned so much from what my mother hadn’t taught me. My mother was good at a lot of things. She was a good teacher and once kept me up until three in the morning drilling me on my multiplication tables, then got me up to make the 8 a.m. school bell that same morning. She was a good nurturer, making sure that I and just about everybody else in our neighborhood was well fed. She was a firm disciplinarian, with strong Mississippi-bred church values. But she wasn’t so good at opening up to me and telling me some things I really needed to know. At age sixteen, I finally heard my mother’s version of the facts of life.

"If you run around here kissin’ these little boys, you’ll come up in a family way."

That was it. I didn’t even know what "pregnant" was. I’d never seen that word. That same year, my mother let me go to the birthday party of a friend. The parents–church members and friends of my mother–weren’t home. A boy there leaned over and kissed me on the mouth. Oh, God. If Mama knew I was up there kissing . . . I would get beheaded. I slapped that boy. Slapped him silly. But I knew it was too late. I knew I was pregnant. I left the party right away and ran home. When Mama came in, I was in the bathroom gagging. I had a toothbrush almost down to my tonsils.

She just stood there. "Gal, what’s wrong with you?"

"I’m gonna have a baby," I declared.

"Oh, my,"she said. "What have you been doing?"

That’s when I told her about the boy kissing me. And instead of her telling me everything was all right, instead of telling me that I couldn’t possibly get in a family way that way, she simply dismissed it, turned, and walked off. And I was left there, all alone with my biggest fear and a toothbrush down my throat. I waited, and waited, and waited for that baby to arrive.

One day, I just couldn’t take it anymore. I worked up the nerve to ask Mama when the baby would be coming. We hadn’t talked about it, so what did I know?

Finally, she said something. "Gal, you’re not pregnant." And that was it. Until I really did become pregnant with Emmett. Eventually, I discovered where babies came from. I learned at the hospital, during labor. In the delivery room, I told the doctors and nurses to get the bedpan because I thought I was having a different kind of problem. And the doctor told me that was the baby. I asked where the baby was coming out and the doctor told me that the baby was coming out the same way he went in. Ooohhh, I was embarrassed to pieces. I should have known that the doctor knew how the baby got there, but I just couldn’t face the doctor knowing that I had slept with a man. Even though the man was my husband. Well, I was pretty educated by the time I got out of the hospital. I surely knew a lot more than I knew when I went in.

Still, I struggled with it all. There had been so many things my mother didn’t tell me; things that might have helped me avoid so many difficulties along the way. I just don’t know what her problem was, but it left me feeling vulnerable. My mother and father were divorced and my stepfather was a very nice man. But it was my mother who always was the source of strength for me. A stately, sturdy woman, who seemed so much taller than five-foot-three, she had the look of someone who could handle anything that came her way. And she always seemed to be guided by traditional values–the kind of things you learned in Sunday school more than everyday school. She taught me these things, how to be a good person, but still something was missing.

There were several incidents that occurred during my early years, events that I wish I had been better prepared to take on. Because I was used to her taking care of me, I thought I could rely on her to handle them, or at least show me she understood. There was this neighbor of ours, one of our church deacons. I was about seven, an only child, and I always loved playing with his children, three girls and a boy. One day he sent all the kids out of his house, but he told me to stay behind with him. He was cooking a turtle and asked me if I wanted to look at it. Of course I did. He picked me up and I looked over in the boiling pot and I could see the turtle’s heart beating. He told me that the turtle’s heart was like a timer, that it would not stop beating until the turtle was done. I was fascinated, but I knew right away that I did not want any turtle soup, or whatever it was he was making. That might have been the only thing I would ever remember about that man, if it hadn’t been for the other thing. He kept holding me up in his arms even though I was getting uncomfortable and told him I wanted to get down, to go out. The other kids had already left and I wanted to be with them, not him.

"No, you’re gonna stay in here with me," he said. Although I was a very naive child, I knew something was wrong. And I was right. He finally set me down, but he didn’t let me leave. He began to pull my pants down. Why was he doing this to me? He was a deacon in our church, a man I was taught to respect, but this was not what a good man was supposed to do. This was bad, and I wasn’t quite sure what I should do about it.

Well, he gave me the answer, by asking the question. "Who you gonna tell?"

"I’m gonna tell my mama," I blurted out without any hesitation. I was afraid and I didn’t know what else to say. I figured my mother could fix anything. She always did.

"Oh, no, you can’t do that," he said, as if he was really surprised by my threat. What did he think I would do?

Then he asked me again, and I repeated that I would tell my mother. I held to it because I meant it. This didn’t seem like something he should be doing, and I was going to tell her. If I could get to her. Finally, I guess he decided it wasn’t worth the risk. He let me go, sent me out to play with the other kids. But I couldn’t wait to tell Mama. What happened next was as surprising to me as what had happened in the first place. When I told Mama everything that had gone on, she didn’t have any reaction. I wanted to know what she was going to do. But she just shooed me off somewhere. She never acted like she thought it was anything of consequence. But she did make me stay around our house from then on. I don’t know to this day whether Mama spoke to that man or not. I can’t help but wonder about it, though.

There was another incident. I was about fourteen by this time, and I wanted to go to a dance with my dearest friend, Ollie Colbert. I could never go to dances. They were just off-limits. But I begged Mam...

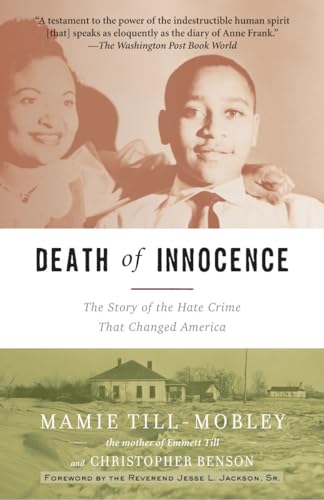

“Death of Innocence reveals Mamie Till-Mobley for what she was: one of the greatest, but largely unsung, heroes in all of African-American history. Her words are powerful; her strength and vision in the face of the unspeakable horror of her son’s death are astonishing. The life and work of Mamie Till-Mobley serves as an inspiration to all who love justice."—Stanley Nelson, executive producer and director of the documentary The Murder of Emmett Till

“Mamie Till-Mobley has written a powerful book in which she reveals to us the life she shared with her son, Emmett Till, and her pride and joy as he became a remarkable young man. This story shows us how the cruelty of a few changed the life of a loving, caring mother and the history of a nation.”—Kadiatou Diallo, author of My Heart Will Cross This Ocean: My Story, My Son, Amadou

“An epic drama of despair and hope. The most powerful personal story, so far, from the civil rights movement.”—Morris Dees, Southern Poverty Law Center

“Mamie Till-Mobley has always deserved our admiration for her insistence that the world know her son’s terrible fate, and for her determination to confront his killers in a Mississippi courtroom. Now, in the final act of her life, she gives us an account of the crime, its victim, and its aftermath that is as historically valuable as it is inspiring.”—Philip Dray, author of At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America

"In the pantheon of Black women I love and admire, Mamie Till-Mobley stands tall. Throughout her memoir...she is as fearless in sharing her life story as she was when she insisted on an open-casket funeral for her beloved son, Emmett. It was wise of Till-Mobley, who died earlier this year at 81, to wait until she could see the end of her journey to tell her story....Throughout her life, Till-Mobley never tried to cash in on her son's death. Instead, she tried to find a way to make sense of it. None of us can really know her pain, but through Death of Innocence we do know her grace. Her book is a story of faith and hope -- but not blind faith and hope; rather faith and hope as action, as being worthy of the challenge."—Nikki Giovanni

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurOne World

- Date d'édition2004

- ISBN 10 0812970470

- ISBN 13 9780812970470

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages320

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,72

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Death of Innocence Format: Paperback

Description du livre Etat : New. Brand New. N° de réf. du vendeur 0812970470

Death Of Innocence : The Story Of The Hate Crime That Changed America

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 3184727-n

Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America

Description du livre Etat : New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. N° de réf. du vendeur bk0812970470xvz189zvxnew

Death of Innocence (Paperback)

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Paperback. The mother of Emmett Till recounts the story of her life, her sons tragic death, and the dawn of the civil rights movementwith a foreword by the Reverend Jesse L. Jackson, Sr. In August 1955, a fourteen-year-old African American, Emmett Till, was visiting family in Mississippi when he was kidnapped from his bed in the middle of the night by two white men and brutally murdered. His crime: allegedly whistling at a white woman in a convenience store. The killers were eventually acquitted. What followed altered the course of this countrys historyand it was all set in motion by the sheer will, determination, and courage of Mamie Till-Mobley, whose actions galvanized the civil rights movement, leaving an indelible mark on our racial consciousness. Death of Innocence is an essential document in the annals of American civil rights history, and a painful yet beautiful account of a mothers ability to transform tragedy into boundless courage and hope. Praise for Death of Innocence A testament to the power of the indestructible human spirit [that] speaks as eloquently as the diary of Anne Frank.The Washington Post Book World With this important book, [Mamie Till-Mobley] has helped ensure that the story of her son (and her own story) will not soon be forgotten. . . . A riveting account of a tragedy that upended her life and ultimately the Jim Crow system.Chicago Tribune The book will . . . inform or remind people of what a courageous figure for justice [Mamie Till-Mobley] was and how important she and her son were to setting the stage for the modern-day civil rights movement.The Detroit News Poignant . . . In his mothers descriptions, Emmett becomes more than an icon; he becomes a living, breathing youngsterany mothers child.Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Powerful . . . [Mamie Till-Mobleys] courage transformed her loss into a moral compass for a nation.Black Issues Book Review Robert F. Kennedy Book Award Special Recognition BlackBoard Nonfiction Book of the Year The heart-wrenching, inspiring, and award-winning memoir by Mamie Till-Mobley, the mother of Emmett Till, an innocent 14-year-old boy who was in the wrong place at the wrong time and paid for it with his life. High school & older. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780812970470

Death of Innocence

Description du livre Etat : New. pp. 320. N° de réf. du vendeur 26956824

Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America

Description du livre Etat : New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-0812970470-new

Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0812970470

Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Buy for Great customer experience. N° de réf. du vendeur GoldenDragon0812970470

Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0812970470

Death Of Innocence: The Story Of The Hate Crime That Changed America

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : Brand New. reprint edition. 320 pages. 8.25x5.25x0.25 inches. In Stock. N° de réf. du vendeur __0812970470