Articles liés à Bridge of Spies

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

THE WATERSPOUT

Shock and awe was not invented for Saddam Hussein. It was invented for Joseph Stalin, and it worked pretty well.

On July 24, 1946, as most of Russia slept, a team of U.S. Navy frogmen guided a heavy steel container to its final resting place in the clear waters of Bikini Lagoon, 2,500 miles west of Honolulu. They stabilized it with cables ninety feet below an anchored amphibious assault ship that gloried in the name LSM-60. The container was made from the conning tower of the USS Salmon, a scrapped navy submarine, and inside it was a working replica of the plutonium bomb that had killed eighty thousand people at Nagasaki the previous year. That evening, on a support vessel outside the lagoon, the frogmen ate T-bone steaks with all the trimmings.

Around the LSM-60, like giant moon shadows on the water’s calm surface, a target fleet of eighty-five more ships spent that night emptied of crew and supplies, with no role left except to sink. One of the closest to the bomb was the USS Arkansas, a 27,000-ton battleship that had carried President Taft to Panama before the First World War and bombarded Cherbourg and Iwo Jima in the Second. For most of her life the only way for a battleship to go down had been with guns blazing, but the nuclear age had changed that. It turned out that with the help of an atom bomb a battleship could go down like a toy in a bath. It could be flicked onto its bow and rammed into the seabed so that its superstructure fell off as if never even bolted on.

Shortly after breakfast time on the morning of the twenty-fifth, the Arkansas was photographed from every angle as the bomb in the steel container was detonated 170 yards from her hull. Cameras in a B-29 bomber twenty-five thousand feet above the lagoon and a little to the south captured the sight of a huge disc of ocean turning white in an instant. That was the water beneath the Arkansas being vaporized.

The shockwave from the initial blast rolled the ship onto her side and ripped off her propellers. A six-thousand-foot column of spray and water, created in about two and a half seconds, then heaved her into a vertical position in which two thirds of her length were clearly visible ten miles away, dwarfed by the largest man-made waterspout in history. She has lain upside down on the floor of the lagoon ever since.

The Arkansas was one of ten ships sunk outright by what came to be known as the Baker shot. It was the second of two nuclear tests conducted at Bikini with undisguised panache as the world adjusted to an awesome new technology (and to the daring swimsuit it inspired; the first-ever bikini, presented in Paris that month, was called l’atome, and the second was a buttock-baring thong described by one fashion writer as what the survivor of a nuclear blast could expect to be wearing as the fireball subsided).

Participation in the tests by U.S. military personnel was voluntary but popular. In shirtsleeves and sunglasses, 37,000 men extended their wartime service for a year to help set up the tests and to see for themselves the power of the weapon that had brought Japan to its knees.

Pat Bradley was there, up a tree with a movie camera on Bikini atoll to film the blast and the tsunami it produced—a single ninety-foot wave that subsided before it hit the island, then three smaller waves. “It took a couple of minutes before the first wave came in to the atoll,” he remembered. “The second came in higher, then the third completely covered the island four to six feet deep.”

A lean and thoughtful young air force captain named Stan Beerli was there too. He had survived the world war in B-17 bombers over Italy and would survive the cold war in the regulation dark suit of the CIA. His tasks would include trying to keep Gary Powers and the U-2 in the shadows where they belonged, but for the time being the cold war was pure spectacle.

The foreign and domestic press were welcome at Bikini. The Baker shot was witnessed by 131 reporters, including a full Soviet contingent. With Warner Bros.’ help, the Pentagon released a propaganda film of the blast for anyone who had missed the initial coverage, and Admiral William “Spike” Blandy, who oversaw the operation, posed with his wife cutting an angel food cake in the shape of a mushroom cloud.

Responding to public anxiety before the blast, Blandy promised that he was “not an atomic playboy” and that the bomb would not “blow out the bottom of the sea and let all the water run down the hole.” This was true, but it could still do a lot of damage. In the summer of 1947 Life magazine published a long article based on official studies of the intense radioactive fallout from the Baker bomb. It concluded that if a similar weapon were to explode off the tip of Manhattan in a stiff southerly wind, two million people would die.

America had finished the war with a pair of atom bombs and started the peace in the same way. President Truman’s message to Stalin could not have been clearer if written in blood. It was a warning not to contemplate starting a new war in Europe trusting in the Red Army’s old-fashioned strength in numbers. And it signaled more concisely than any speech that Truman had accepted the central argument of George Kennan’s famous “Long Telegram,” sent from the U.S. embassy in Moscow six months before the tests: the Soviet Union had to be contained. As Truman himself put it: “If we could just have Stalin and his boys see one of these things, there wouldn’t be any question about another war.”

Stalin refused to be intimidated. He had not sacrificed twenty million people to defeat Fascism only to be told where to set the limits on Stalinism. And yet he had a problem.

At the time of the Bikini tests, the Soviet Union was still three years and a month from exploding its first nuclear weapon. Its efforts to build one were under way on a bend in the Shagan River in eastern Kazakhstan, under the direction of a bearded young hero of Soviet science (and tightly closeted homosexual) named Igor Kurchatov. Stalin had deemed the bomb “Problem Number One.” He had created a special state committee to ensure that no expense was spared in solving it. Whole mountains in Bulgaria had been commandeered to give Kurchatov the uranium he needed. But Kurchatov was not an innovator. He was a nuclear plagiarist, almost completely dependent on intelligence from left-leaning scientists in the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos. As he admitted in a 1943 memo to the Council of People’s Commissars, this flow of intelligence had “immense, indeed incalculable importance for our State and science”—but in 1946 the flow had slowed suddenly to a trickle.

Just a year earlier, not one but two descriptions of the first bomb tested at Los Alamos were in the Kremlin nearly two weeks before it even exploded. After that test, more detailed diagrams of the device reached Moscow than were provided in the first official nuclear report to Congress. One was smuggled out of Albuquerque in a box of Kleenex. Atomic espionage was never more bountiful than this. But on November 7, 1945, Elizabeth Terrill Bentley, a thirty-seven-year-old graduate of Vassar and a paid-up Soviet agent, went to the FBI with a 107-page description of Soviet intelligence activities in North America. The following day J. Edgar Hoover sent a secret memo to the White House based on Bentley’s material. It produced few arrests because she offered scant supporting evidence, but her defection forced Moscow to shut down most of the channels feeding nuclear secrets to Kurchatov.

There were other reasons why Soviet espionage in the United States was grinding to a halt. Victory in the war had removed the most compelling reason for scientists at Los Alamos to share designs with their former Soviet allies—the defeat of Nazism. And the U.S. Army had at last begun decoding encrypted Soviet cable traffic, code-named Venona, that corroborated many of Bentley’s allegations.

Without vital intelligence from the true pioneers of nuclear fission in New Mexico, Kurchatov would not be able to complete the bomb. Without the bomb, the most that the Soviet empire could hope to do was defend its interminable frontiers. As the Bikini lagoon erupted, the outlook for international Communism looked bleak indeed. Yet from the bowels of the Lyubianka—headquarters of the KGB and the true engine room of the revolution—there came a glimmer of hope.

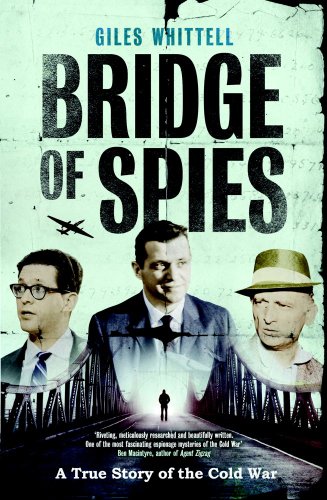

Bridge of Spies is a true story of three men - Rudolf Abel, a Soviet Spy who was a master of disguise; Gary Powers, an American who was captured when his spy plane was shot down by the Russians; and Frederic Pryor, a young American doctor mistakenly identified as a spy and captured by the Soviets. The men in this three-way political swap had been drawn into the nadir of the Cold War by duty and curiosity, and the same tragicomedy of errors that induced Khrushchev to send missiles to Castro. Two of them - the spy and the pilot - were the original seekers of weapons of mass destruction. The third was an intellectual, in over his head. They were rescued against daunting odds by fate and by their families, and then all but forgotten. Even the U2 spy-plane pilot Powers is remembered now chiefly for the way he was vilified in the U.S. on his return. Yet the fates of those men exemplified the pathological mistrust that fueled the arms race for the next 30 years. This is their story.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurSimon & Schuster

- Date d'édition2011

- ISBN 10 0857201638

- ISBN 13 9780857201638

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Nombre de pages304

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,97

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Bridge of Spies

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0857201638

Bridge of Spies

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0857201638