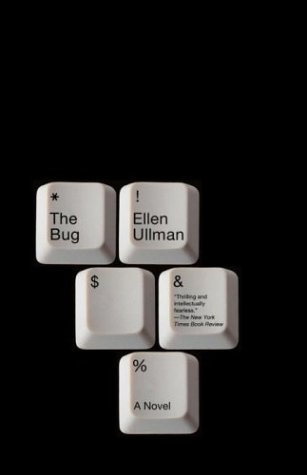

Articles liés à The Bug

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNBook by Ullman Ellen

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Extrait :

The PAUSE

A computer can execute millions of instructions in a second. The human brain, in comparison, is painfully slow. The memories of a single year, for instance, took me a full thirty seconds to recall. Which is a long time if you think about it. Imagine a second-hand sweep going tick by tick halfway around the face of a clock. Or the digital readout of light-emitting diodes, with their blink, blink--thirty blinks--as they count off time.

"Passport, please."

The immigration agent at the San Francisco airport was a pleasant-faced young man, not at all threatening, the sort who does his job without particular fervor.

"Countries visited?"

It's right on the landing card, I wanted to say, but I'd learned not to be belligerent in circumstances like these. "One. The Dominican Republic."

He kept his face toward me, a certain blankness undoing his pleasant expression, as his hand disappeared under the counter of the little booth that stood between us. I knew he was putting my passport through a scanner. The first page of the United States passport has been machine-readable for years.

Then we waited.

"Nice trip, Miss, uh . . ."

"Ms. Walton. Yes."

"Roberta Walton."

"Yes."

The immigration agent looked down at his computer terminal, his hands still under the counter of the booth.

Then he said, "Good weather there this time of year?"

"Hot. Yes."

"Humid?"

"Yes. Not too bad."

Chitchat. Filler. His face trying to take on its pleasant expression again. Undone by his eyes flicking toward the screen half hidden under a shelf in the corner of the booth. He was waiting for an answer. Should I be allowed to pass, or should I be questioned? Was I what I seemed to be: an innocuous middle-aged woman who'd gone to get herself some sun in mid-November? Or was I a well-disguised drug runner, money launderer, sex slaver? He could do nothing until he heard from the system.

And so we waited. Tick-tock, blink-blink, thirty seconds stretched themselves out one by one, a hole in human experience. Waiting for the system: life today is full of such pauses. The soft clacking of computer keys, then the voice on the telephone telling you, "Just a moment, please." The credit-card reader instructing you "Remove card quickly!" then displaying "Processing. Please wait." The little hourglass icon on your computer screen reminding you how time is passing and there is nothing you can do about it. The diddler at the bottom of the browser screen going back and forth, back and forth like a caged crazed animal. All the hours the computer is supposedly saving us--I don't believe it, in the sum of things, I thought as I stood there leaning on my luggage cart. It has filled our lives with little wait states like this one, useless wait states, little slices of time in which you can't do anything at all but stand there, sit there, hold the phone--the sort of unoccupied little slices of time no decent computer operating system would tolerate for itself. A computer, waiting like this, would find something useful to do: check for other processes wanting attention, flush a file buffer, refresh a cache, at least.

Which is what I suppose my mind began doing with the pause at the immigration counter: some mysterious housekeeping process of the brain, some roaming through the backwaters of the synapses, trolling memory, cleaning lost connections . . .

It's the Telligentsia database! came the thought out of somewhere. Then came an understanding, step by step, like a syllogism: The system we're waiting for was made by Telligentsia. Telligentsia, where my technical life began. So it's my fault. This particular wait state is something I myself helped visit upon the world!

I looked behind the counter at the agent's terminal: Yes. That damned transaction interface. The Immigration Service was one of our first customers. In 1986, they were going to "revolutionize" international arrivals with our database. And here it still was after all these years, our software, its transaction interface, that sluggish component we testers had complained about to the programmers, too slow, too slow, who'll put up with this waiting? Ah, I saw how the immigration agent had learned to tolerate this waiting. A certain suspension of himself; an unattractive slackness in his body, his mouth; a gone-to-nowhere look in his already vague eyes. Odd how adaptable human beings are. The programmers had long accustomed themselves to waiting on machines, and then we, the software testers, soon adapted; and with every shipment of our software, out it spread like a virus to the world: human beings everywhere learning to suspend themselves, go elsewhere for little slits of time, not exactly talking or working or doing anything, since any moment--you never know which one--the system may come back, respond, give you the answer.

The long thirty seconds . . . Funny: It was the same pause we complained about. Strange how in all this time no one had tuned or fixed it. But of course it was still there. Who could have possibly worked on it? Soon after we went public, Telligentsia was sold off to another company, then that company was sold off as well, and our software disappeared further and further into the hands of people who'd never met us. Who would there be in all those changes to remember our problems, our arguments, the things we tried and abandoned? Funny to think of the code remaining there, unchanged, as it passed from hand to hand, newer and newer layers of code laid down over it like sediment. And inside--deep inside, in the places no one understood anymore so they just left them alone because that part of the code seemed to work--down in there the long pause still lived. The programmers and testers had moved on, changed, grown older, but here was the code, frozen, mindlessly running itself over and over: thoughtless robotic artifact of the lives that created it.

Ethan Levin.

Through the time tunnel of the long pause came his name. Ethan Levin, Telligentsia's senior engineer for client-side computing, inadvertent creator of the bug officially designated UI-1017. I tried to push him away. Standing there sweating by my luggage cart, I was not ready to remember what happened to him. UI-1017: the one thousand seventeenth bug in the user interface. One thousand and sixteen had come before it; thousands more would come after; and so what? Let it alone, I told myself. Don't dwell on this one ruined life. The world has moved on to other follies involving other programmers. Everyone seems so happy with the world we technical people have created. See here: even the immigration agent, after his little wait at his terminal, has gotten his answer, and now a real smile makes his empty, pleasant face almost remarkable as he taps data into his keyboard.

But Ethan Levin would not go away. That relentless bug of his I found, what happened to him while it came and went, what I might have done and didn't--all that was waiting for me in the long thirty-second pause. There was no way out now. There was no way to go home and forget all over again what had happened. I would have to remember the database as I first saw it, in the late fall of 1983. I would have to remember when I was a failed academic, a linguist with a Ph.D. during the Ph.D. glut of the 1980s, itinerant untenured instructor of Linguistics 101, desperate striver out of the lumpen professoriat. And how I became--through the recommendation of a friend, unbelievable to anyone who'd known me--a junior quality-assurance "engineer" at the start-up software company called Telligentsia. Where I was the primary tester of one Ethan Levin, a skinny, apparently confident man of thirty-six who'd been programming for twelve seemingly accomplished years when the bug designated UI-1017 first found him.

Time circled back on itself. Nineteen eighty-four. The IBM PC was three years old; the Apple Macintosh had just been released. I was seeing for the first time the famous Super Bowl ad that introduced the Mac to the world: The woman in running shorts breaking into the auditorium where men, dressed alike like prisoners, sat mute before a screen. On the screen that same huge head lit by a blue light--Big Brother, IBM, known as Big Blue for the color of the company's logo. And all over again, I knew what the woman must do.

And then she did it: she reeled and hurled a hammer at the screen, smashing it, breaking the prisoners' spell.

Rejoice! The age of the behemoth corporate computer was over. Individuals would now have computing power in their own hands. Somehow this would change everything. Oh, what a perfect advertising moment! The smashed specter of 1984. And done by a woman. Geraldine Ferraro was running for the vice presidency of the United States, the first-ever women's marathon would be run at the Olympics, so why shouldn't a woman in running shorts symbolize the end of technological tyranny?

"Welcome home, Ms. Walton."

The immigration agent, smiling pleasantly out of his pleasant face, offering me back my passport.

I only stared at it. I didn't want to touch that passport now. The whole story would open up out of its pages.

Tap, tap: the agent touching the passport to the counter.

"Thank you," I said, not meaning it.

Everything was in order. Page stamped, passport returned. The date and port of my arrival duly recorded by the system. The old database--traitor, time shifter--had not confused me with a terrorist. Later someone would enter the data from my landing card: where I'd been, for what purpose, how much I'd spent, on what. And later yet, some researcher might pore over the great masses of data accumulated in our marvelous Telligentsia database (maybe using the "data mining" software from the second start-up company I worked for). And he'd learn how frequent...

Revue de presse :

A computer can execute millions of instructions in a second. The human brain, in comparison, is painfully slow. The memories of a single year, for instance, took me a full thirty seconds to recall. Which is a long time if you think about it. Imagine a second-hand sweep going tick by tick halfway around the face of a clock. Or the digital readout of light-emitting diodes, with their blink, blink--thirty blinks--as they count off time.

"Passport, please."

The immigration agent at the San Francisco airport was a pleasant-faced young man, not at all threatening, the sort who does his job without particular fervor.

"Countries visited?"

It's right on the landing card, I wanted to say, but I'd learned not to be belligerent in circumstances like these. "One. The Dominican Republic."

He kept his face toward me, a certain blankness undoing his pleasant expression, as his hand disappeared under the counter of the little booth that stood between us. I knew he was putting my passport through a scanner. The first page of the United States passport has been machine-readable for years.

Then we waited.

"Nice trip, Miss, uh . . ."

"Ms. Walton. Yes."

"Roberta Walton."

"Yes."

The immigration agent looked down at his computer terminal, his hands still under the counter of the booth.

Then he said, "Good weather there this time of year?"

"Hot. Yes."

"Humid?"

"Yes. Not too bad."

Chitchat. Filler. His face trying to take on its pleasant expression again. Undone by his eyes flicking toward the screen half hidden under a shelf in the corner of the booth. He was waiting for an answer. Should I be allowed to pass, or should I be questioned? Was I what I seemed to be: an innocuous middle-aged woman who'd gone to get herself some sun in mid-November? Or was I a well-disguised drug runner, money launderer, sex slaver? He could do nothing until he heard from the system.

And so we waited. Tick-tock, blink-blink, thirty seconds stretched themselves out one by one, a hole in human experience. Waiting for the system: life today is full of such pauses. The soft clacking of computer keys, then the voice on the telephone telling you, "Just a moment, please." The credit-card reader instructing you "Remove card quickly!" then displaying "Processing. Please wait." The little hourglass icon on your computer screen reminding you how time is passing and there is nothing you can do about it. The diddler at the bottom of the browser screen going back and forth, back and forth like a caged crazed animal. All the hours the computer is supposedly saving us--I don't believe it, in the sum of things, I thought as I stood there leaning on my luggage cart. It has filled our lives with little wait states like this one, useless wait states, little slices of time in which you can't do anything at all but stand there, sit there, hold the phone--the sort of unoccupied little slices of time no decent computer operating system would tolerate for itself. A computer, waiting like this, would find something useful to do: check for other processes wanting attention, flush a file buffer, refresh a cache, at least.

Which is what I suppose my mind began doing with the pause at the immigration counter: some mysterious housekeeping process of the brain, some roaming through the backwaters of the synapses, trolling memory, cleaning lost connections . . .

It's the Telligentsia database! came the thought out of somewhere. Then came an understanding, step by step, like a syllogism: The system we're waiting for was made by Telligentsia. Telligentsia, where my technical life began. So it's my fault. This particular wait state is something I myself helped visit upon the world!

I looked behind the counter at the agent's terminal: Yes. That damned transaction interface. The Immigration Service was one of our first customers. In 1986, they were going to "revolutionize" international arrivals with our database. And here it still was after all these years, our software, its transaction interface, that sluggish component we testers had complained about to the programmers, too slow, too slow, who'll put up with this waiting? Ah, I saw how the immigration agent had learned to tolerate this waiting. A certain suspension of himself; an unattractive slackness in his body, his mouth; a gone-to-nowhere look in his already vague eyes. Odd how adaptable human beings are. The programmers had long accustomed themselves to waiting on machines, and then we, the software testers, soon adapted; and with every shipment of our software, out it spread like a virus to the world: human beings everywhere learning to suspend themselves, go elsewhere for little slits of time, not exactly talking or working or doing anything, since any moment--you never know which one--the system may come back, respond, give you the answer.

The long thirty seconds . . . Funny: It was the same pause we complained about. Strange how in all this time no one had tuned or fixed it. But of course it was still there. Who could have possibly worked on it? Soon after we went public, Telligentsia was sold off to another company, then that company was sold off as well, and our software disappeared further and further into the hands of people who'd never met us. Who would there be in all those changes to remember our problems, our arguments, the things we tried and abandoned? Funny to think of the code remaining there, unchanged, as it passed from hand to hand, newer and newer layers of code laid down over it like sediment. And inside--deep inside, in the places no one understood anymore so they just left them alone because that part of the code seemed to work--down in there the long pause still lived. The programmers and testers had moved on, changed, grown older, but here was the code, frozen, mindlessly running itself over and over: thoughtless robotic artifact of the lives that created it.

Ethan Levin.

Through the time tunnel of the long pause came his name. Ethan Levin, Telligentsia's senior engineer for client-side computing, inadvertent creator of the bug officially designated UI-1017. I tried to push him away. Standing there sweating by my luggage cart, I was not ready to remember what happened to him. UI-1017: the one thousand seventeenth bug in the user interface. One thousand and sixteen had come before it; thousands more would come after; and so what? Let it alone, I told myself. Don't dwell on this one ruined life. The world has moved on to other follies involving other programmers. Everyone seems so happy with the world we technical people have created. See here: even the immigration agent, after his little wait at his terminal, has gotten his answer, and now a real smile makes his empty, pleasant face almost remarkable as he taps data into his keyboard.

But Ethan Levin would not go away. That relentless bug of his I found, what happened to him while it came and went, what I might have done and didn't--all that was waiting for me in the long thirty-second pause. There was no way out now. There was no way to go home and forget all over again what had happened. I would have to remember the database as I first saw it, in the late fall of 1983. I would have to remember when I was a failed academic, a linguist with a Ph.D. during the Ph.D. glut of the 1980s, itinerant untenured instructor of Linguistics 101, desperate striver out of the lumpen professoriat. And how I became--through the recommendation of a friend, unbelievable to anyone who'd known me--a junior quality-assurance "engineer" at the start-up software company called Telligentsia. Where I was the primary tester of one Ethan Levin, a skinny, apparently confident man of thirty-six who'd been programming for twelve seemingly accomplished years when the bug designated UI-1017 first found him.

Time circled back on itself. Nineteen eighty-four. The IBM PC was three years old; the Apple Macintosh had just been released. I was seeing for the first time the famous Super Bowl ad that introduced the Mac to the world: The woman in running shorts breaking into the auditorium where men, dressed alike like prisoners, sat mute before a screen. On the screen that same huge head lit by a blue light--Big Brother, IBM, known as Big Blue for the color of the company's logo. And all over again, I knew what the woman must do.

And then she did it: she reeled and hurled a hammer at the screen, smashing it, breaking the prisoners' spell.

Rejoice! The age of the behemoth corporate computer was over. Individuals would now have computing power in their own hands. Somehow this would change everything. Oh, what a perfect advertising moment! The smashed specter of 1984. And done by a woman. Geraldine Ferraro was running for the vice presidency of the United States, the first-ever women's marathon would be run at the Olympics, so why shouldn't a woman in running shorts symbolize the end of technological tyranny?

"Welcome home, Ms. Walton."

The immigration agent, smiling pleasantly out of his pleasant face, offering me back my passport.

I only stared at it. I didn't want to touch that passport now. The whole story would open up out of its pages.

Tap, tap: the agent touching the passport to the counter.

"Thank you," I said, not meaning it.

Everything was in order. Page stamped, passport returned. The date and port of my arrival duly recorded by the system. The old database--traitor, time shifter--had not confused me with a terrorist. Later someone would enter the data from my landing card: where I'd been, for what purpose, how much I'd spent, on what. And later yet, some researcher might pore over the great masses of data accumulated in our marvelous Telligentsia database (maybe using the "data mining" software from the second start-up company I worked for). And he'd learn how frequent...

“Thrilling and intellectually fierce. . . . The novel of ideas is alive and well.”—The New York Times Review of Books

“Takes the techno-novel to a new level of literary excellence. . . . Ullman resembles Kafka in the way she writes so vividly and clearly about states of paranoid anxiety. . . . This is magnetic fiction.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“Ardent, brilliantly tactile. . . . Offers endless systems twists and turns. Technophiles can revel in its UNIX complexities while the rest of us delight in its user-friendly explanations, but the moral conundra The Bug poses are far more rewarding, and discomfiting.”—Newsday

“Extraordinary. . . . This fascinating tale leaves the reader wondering about the line between science and art, analysis and feeling. . . . Perfect for our time.”—USA Today

“No one writes more eloquently than Ullman about the peculiar mind-set of the people who create the digital tools we use every day. . . A thriller-like tale of hubris and self-destruction that never stoops to cheap tricks. . . . At stake is not just the program, but the fragile belief that we can master ourselves and our fates.” –Laura Miller, Salon

“Suspenseful. . . Think Mary Shelley in the Silicon Valley.” –Elle

“A fascinating literary study of an often-misunderstood culture.” –Chicago Tribune

“A blistering novel about love, hate, and psychopathy. . . At its best, [it] finds in computers the same eerie allure that DeLillo’s White Noise found in televisions.”–Kirkus Reviews

“Illuminating. . . . a combination of poetic and philosophical sensibilities that plumb the abstruse depths of technological creation.” –Publishers Weekly

“Ullman is a rarity, a software engineer who is also a wonderful writer.” –New Scientist

“The Bug should be read by every software developer–and every end user who has ever experienced a software crash–if only to know that they're not alone in their endless fight against the almost-alive malignancies hiding in code.” –IEEE Spectrum

“Ullman is dead-on in her depiction[s]. . . . A deeply humanistic and surprisingly old-fashioned work.” –Library Journal

“Ullman writes unsparingly of the vivid, compelling, emotionally driven souls who gave us our new machines. By turns love story, tense psychological drama, and comedy of (very bad) manners, The Bug is an edgy and irresistible journey into lives all too rarely visited by literary types.”–Geraldine Brooks, author of A Year of Wonders

“Takes the techno-novel to a new level of literary excellence. . . . Ullman resembles Kafka in the way she writes so vividly and clearly about states of paranoid anxiety. . . . This is magnetic fiction.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“Ardent, brilliantly tactile. . . . Offers endless systems twists and turns. Technophiles can revel in its UNIX complexities while the rest of us delight in its user-friendly explanations, but the moral conundra The Bug poses are far more rewarding, and discomfiting.”—Newsday

“Extraordinary. . . . This fascinating tale leaves the reader wondering about the line between science and art, analysis and feeling. . . . Perfect for our time.”—USA Today

“No one writes more eloquently than Ullman about the peculiar mind-set of the people who create the digital tools we use every day. . . A thriller-like tale of hubris and self-destruction that never stoops to cheap tricks. . . . At stake is not just the program, but the fragile belief that we can master ourselves and our fates.” –Laura Miller, Salon

“Suspenseful. . . Think Mary Shelley in the Silicon Valley.” –Elle

“A fascinating literary study of an often-misunderstood culture.” –Chicago Tribune

“A blistering novel about love, hate, and psychopathy. . . At its best, [it] finds in computers the same eerie allure that DeLillo’s White Noise found in televisions.”–Kirkus Reviews

“Illuminating. . . . a combination of poetic and philosophical sensibilities that plumb the abstruse depths of technological creation.” –Publishers Weekly

“Ullman is a rarity, a software engineer who is also a wonderful writer.” –New Scientist

“The Bug should be read by every software developer–and every end user who has ever experienced a software crash–if only to know that they're not alone in their endless fight against the almost-alive malignancies hiding in code.” –IEEE Spectrum

“Ullman is dead-on in her depiction[s]. . . . A deeply humanistic and surprisingly old-fashioned work.” –Library Journal

“Ullman writes unsparingly of the vivid, compelling, emotionally driven souls who gave us our new machines. By turns love story, tense psychological drama, and comedy of (very bad) manners, The Bug is an edgy and irresistible journey into lives all too rarely visited by literary types.”–Geraldine Brooks, author of A Year of Wonders

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurAnchor Books

- Date d'édition2004

- ISBN 10 1400032350

- ISBN 13 9781400032358

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages353

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 57,83

Frais de port :

EUR 3,87

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

THE BUG

Edité par

Anchor

(2004)

ISBN 10 : 1400032350

ISBN 13 : 9781400032358

Neuf

Couverture souple

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.6. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-1400032350

Acheter neuf

EUR 57,83

Autre devise