Articles liés à Brother, I'm Dying

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

On Sunday, October 24, 2004, nearly two months after he left New York, Uncle Joseph woke up to the clatter of gunfire. There were blasts from pistols, handguns, automatic weapons, whose thundering rounds sounded like rockets. It was the third of such military operations in Bel Air in as many weeks, but never had the firing sounded so close or so loud. Looking over at the windup alarm clock on his bedside table, he was startled by the time, for it seemed somewhat lighter outside than it should have been at four thirty on a Sunday morning.

During the odd minutes it took to reposition and reload weapons, you could hear rocks and bottles crashing on nearby roofs. Taking advantage of the brief reprieve, he slipped out of bed and tiptoed over to a peephole under the staircase outside his bedroom. Parked in front of the church gates was an armored personnel carrier, a tank with mounted submachine guns on top. The tank had the familiar circular blue and white insignia of the United Nations peacekeepers and the letters UN painted on its side. Looking over the trashstrewn alleys that framed the building, he thought for the first time since he’d lost Tante Denise that he was glad she was dead. She would have never survived the gun blasts that had rattled him out of his sleep. Like Marie Micheline, she too might have been frightened to death.

He heard some muffled voices coming from the living room below, so he grabbed his voice box and tiptoed down the stairs. In the living room, he found Josiane and his grandchildren: Maxime, Nozial, Denise, Gabrielle and the youngest, who was also named Joseph, after him. Léone, who was visiting from Léogâne, was also there, along with her brothers, Bosi and George.

“Ki jan nou ye?” my uncle asked. How’s everyone?

“MINUSTAH plis ampil police,” a trembling Léone tried to explain.

Like my uncle, Léone had spent her entire life watching the strong arm of authority in action, be it the American marines who’d been occupying the country when she was born or the brutal local army they’d trained and left behind to prop up, then topple, the puppet governments of their choice. And when the governments fell, United Nations soldiers, so-called peacekeepers, would ultimately have to step in, and even at the cost of innocent lives attempt to restore order.

Acting on the orders of the provisional government that had replaced Aristide, about three hundred United Nations soldiers and Haitian riot police had come together in a joint operation to root out the most violent gangs in Bel Air that Sunday morning. Arriving at three thirty a.m., the UN soldiers had stormed the neighborhood, flattening makeshift barricades with bulldozers. They’d knocked down walls on corner buildings that could be used to shield snipers, cleared

away piles of torched cars that had been blocking traffic for weeks and picked up some neighborhood men.

“It is a physical sweep of the streets,” Daniel Moskaluk, the spokesman for the UN trainers of the Haitian police, would later tell the Associated Press, “so that we can return to normal traffic in this area, or as normal as it can be for these people.”

Before my uncle could grasp the full scope of the situation, the shooting began again, with even more force than before. He gathered everyone in the corner of the living room that was farthest from Rue Tirremasse, where most of the heavy fire originated. Crouched next to his grandchildren, he wondered what he would do if they were hit by a stray. How would he get them to a hospital?

An hour passed while they cowered behind the living room couch. There was another lull in the shooting, but the bottle and rock throwing continued. He heard something he hadn’t heard in some time: people were pounding on pots and pans and making clanking noises that rang throughout the entire neighborhood. It wasn’t the first time he’d heard it, of course. This kind of purposeful rattle was called bat tenèb, or beating the darkness. His neighbors, most of them now dead, had tried to beat the darkness when Fignolé had been toppled so many decades ago. A new generation had tried it again when Aristide had been removed both times. My uncle tried to imagine in each clang an act of protest, a cry for peace, to the Haitian riot police, to the United Nations soldiers, all of whom were supposed to be protecting them. But more often it seemed as if they were attacking them while going after the chimères, or ghosts, as the gang members were commonly called.

The din of clanking metal rose above the racket of roofdenting rocks. Or maybe he only thought so because he was so heartened by the bat tenèb. Maybe he wouldn’t die today after all. Maybe none of them would die, because their neighbors were making their presence known, demanding peace from the gangs as well as from the authorities, from all sides.

He got up and cautiously peeked out of one of the living room windows. There were now two UN tanks parked in front of the church. Thinking they’d all be safer in his room, he asked everyone to go with him upstairs.

Maxo had been running around the church compound looking for him. They now found each other in my uncle’s room. The lull was long enough to make them both think the gunfight might be over for good. Relieved, my uncle showered and dressed, putting on a suit and tie, just as he had every other Sunday morning for church.

Maxo ventured outside to have a look. A strange calm greeted him at the front gate. The tanks had moved a few feet, each now blocking one of the alleys joining Rue Tirremasse and the parallel street, Rue Saint Martin. Maxo had thought he might sweep up the rocks and bottle shards and bullet shells that had landed in front of the church, but in the end he decided against it.

Another hour went by with no shooting. A few church members arrived for the regular Sunday-morning service.

“I think we should cancel today,” Maxo told his father when they met again at the front gate.

“And what of the people who are here?” asked my uncle. “How can we turn them away? If we don’t open, we’re showing our lack of faith. We’re showing that we don’t trust enough in God to protect us.”

At nine a.m., they opened the church gates to a dozen or so parishioners. They decided, however, not to use the mikes and loudspeakers that usually projected the service into the street.

A half hour into the service, another series of shots rang out. My uncle stepped off the altar and crouched, along with Maxo and the others, under a row of pews. This time, the shooting lasted about twenty minutes. When he looked up again at the clock, it was ten a.m. Only the sound of sporadic gunfire could be heard at the moment that a dozen or so Haitian riot police officers, the SWAT-like CIMO (Corps d’Intervention et de Maintien de l’Ordre, or Unit for Intervention

and Maintaining Order), stormed the church. They were all wearing black, including their helmets and bulletproof vests, and carried automatic assault rifles as well as sidearms, which many of them aimed at the congregation. Their faces were covered with dark knit masks, through which you could see only their eyes, noses and mouths.

The parishioners quivered in the pews; some sobbed in fear as the CIMO officers surrounded them. The head CIMO lowered his weapon and tried to calm them.

“Why are you all afraid?” he shouted, his mouth looking like it was floating in the middle of his dark face. When he paused for a moment, it maintained a nervous grin.

“If you truly believe in God,” he continued, “you shouldn’t be afraid.”

My uncle couldn’t tell whether he was taunting them or comforting them, telling them they were fine or prepping them for execution.

“We’re here to help you,” the lead officer said, “to protect you against the chimères.”

No one moved or spoke.

“Who’s in charge here?” asked the officer.

Someone pointed at my uncle.

“Are there chimères here?” the policeman shouted in my uncle’s direction.

Gang members inside his church? My uncle didn’t want to think there were. But then he looked over at all the unfamiliar faces in the pews, the many men and women who’d run in to seek shelter from the bullets. They might have been chimères, gangsters, bandits, killers, but most likely they were ordinary people trying to stay alive.

“Are you going to answer me?” the lead officer sternly asked my uncle.

“He’s a bèbè,” shouted one of the women from the church. She was trying to help my uncle. She didn’t want them to hurt him. “He can’t speak.”

Frustrated, the officer signaled for his men to split the congregation into smaller groups.

“Who’s this?” they randomly asked, using their machine guns as pointers. “Who’s that?”

When no one would answer, the lead officer signaled for his men to move out. As they backed away, my uncle could see another group of officers climbing the outside staircase toward the building’s top floors. The next thing he heard was another barrage of automatic fire. This time it was coming from above him, from the roof of the building.

The shooting lasted another half hour. Then an eerie silence followed, the silence of bodies muted by fear, uncoiling themselves from protective poses, gently dusting off their shoulders and backsides, afraid to breathe too loud. Then working together, the riot police and the UN soldiers, who often collaborated on such raids, jogged down the stairs in an organized stampede and disappeared down the street.

After a while my uncle walked to the church’s front gate ...

–Frank Houston, Broward Palm Beach News

“More than just another family immigration; Danticat draws up a balance sheet of what is gained and lost from what seems like such a small decision as where to live and work. Her skills as a storyteller lend themselves well to this story, her own ‘origin myth.’”

–Kel Munger, Sacramento News & Review

“[Brother, I’m Dying] ties in the personal and the national into a document of witness, a combination of journalistic and literary roles. . . . As the book opens in 2004, her father is dying in the U.S. of pulmonary fibrosis. At the same time, life for her relatives in Haiti continues to be perilous, in a more violent and literal way than first-world residents will typically ever experience . . . Danticat’s prose is simple, unadorned, perceptive and unsparing. There is room for compassion in her work but not for pity, strengthening the emotional honesty of her work.”

–Luciana Lopez, The Oregonian

“[Danticat’s] prose is lean and strides confidently between Haiti and America, between flashes of political uprising and the immovable force of bureaucracy. . . . The author’s reportorial tone keeps the glaring indignities suffered by her uncle at the end of his life in clear view. She builds her case like a lawyer who deftly freezes a time line at poignant scenes. She does not look away.”

–Jill Coley, Charleston Post and Courier

“Edwidge Danticat recounts [her uncle]’s last days on earth with heartbreaking precision and beloved depth . . . What’s startling is that Danticat’s precision and depth don’t ever ire toward anger at the authorities . . . [Danticat] takes a storyteller’s grace and makes of it a memoir as robust and fitting as the life itself. . . . [W]e salute Edwidge Danticat, whose stand against tyranny and untruth shows . . . spirit–and courage.”

–John Hood, Miami SunPost

“Danticat’s memoir follows the uncle who was her ‘second father,’ Joseph Danticat. Through his story, she presents another inside view of Haiti, depicting the country’s possibilities as well as its tragedies. . . . Eventually, at 81, targeted by local gangs, Joseph must flee to the United States in 2004, here his story takes an infuriating and tragic turn. Despite his valid visa and passport, U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers detain him and place him in Krome Detention Center . . . Here, Brother, I’m Dying shifts into a moving polemic about discrepancies in U.S. immigration policy. Joseph’s story obviously speaks to the multitude of troubles that have mired Haiti since its independence in 1804. But the process that reduces an undoubtedly great man to Alien 27041999 has its troubles as well.”

–Vikas Turakhia, St. Petersburg Times

“Powerful . . . Edwidge Danticat employs the charms of a storyteller and the authority of a witness to evoke the political forces and personal sacrifices behind her parents’ journey to this country and her uncle’s decision to stay behind. . . . Danticat interweaves the story of her childhood spent between her two ‘papas’ with the final months of both men’s lives, which happened to coincide with her first pregnancy. In the process, Brother, I’m Dying . . . illustrates the large shadow cast by political and personal legacies over both the past and the future. At age 12, Danticat was finally granted a visa to go to the United States. With great economy, she conveys in a brief scene at the American consulate the complex attraction and revulsion that aspiring immigrants and their adoptive country hold for each other. . . . As le consul stamps the application of Edwidge and her brother, he tells them that they are now free to be with their parents, for better or for worse. As insensitive as this treatment is, the question drives much of Brother, I’m Dying, and its answer is neither clear nor easy.”

–Bliss Broyard, The Washington Post Book World

“Something magical happens when prize-winning novelist Edwidge Danticat strings words together. From the most trivial details to breathtaking moments of enormous gravity, Danticat uses words as charms that gently beckon readers into her world and make them sigh, smile, laugh and weep.

Crafted in Danticat’s signature precise, unflinching prose, her latest, Brother I’m Dying, is yet another revelation. In just three words, the title encompasses the memoir’s essence: It’s about family and it’s about death. Within those parameters, Danticat unfolds her heart-wrenching, intimate and true stories.

In July 2004, just as she accepts that her father will succumb to pulmonary fibrosis, Danticat learns that she is carrying her first child. . . . Seamlessly, she interweaves inherited stories, folktales and village lore (the chapter titled ‘The Angel of Death and Father God’ is a stunner). The result is both testament to a past generation and a gift to the next, especially her then-unborn daughter. . . . While Danticat’s previous books have covered some of the worst of atrocities, her prowess as a writer allows her to tell her stories in nuanced, elegant prose. This memoir is no different. Through the seemingly effortless grace of Danticat’s words, a family’s tragedy is transformed into a promise of collective hope.”

–Terry Hong, San Francisco Chronicle

“[Danticat’s] ability to render large complex stories in compact format is powerfully evident in her new memoir, Brother, I’m Dying . . . She comes head-on at the painful tale she has to tell, with results that are both eloquent and devastating. . . . Danticat, drawing on her own memories, family reminisces and U.S. government documentation, makes vivid every stage of [her] fractured family history. In her hands, the distance between experience as it’s lived and experience as it’s rendered on the page all but disappears. A sentence as spare and unadorned as ‘Wrong was now the norm,’ for instance, has a power beyond anything you might expect, simply because of its careful placement in Danticat’s flow of recollection. This is an author who hits her targets with minimum fuss. Danticat is also an author with a political point to make. . . . The story of [her Uncle] Joseph’s death at the hands of a fumbling, unsympathetic bureaucracy is harrowing. . . . If you have any interest in why would-be immigrants risk so much to reach this country, you will have to read Danticat. And if you already have an interest in Danticat, you will want to read this book.”

–Michael Upchurch, The Seattle Times

“Danticat, a writer of deceptively cool prose, here recalling family tragedies, pitches the emotions just right. There are no manipulative plays for tears but only measured accounts of horrors: The current [Haitian] regime’s bully boys, the Tonton Macoute, forbid her uncle to see his granddaughter; a cousin so terrified by an armed attack that she suffers a fatal heart attack; and immigrant authorities confiscate her uncle’s vital medications. Each is searingly effective. . . . Danticat has written a loving tribute and a sobering reminder of the toll that poverty and turbulent politics exact.”

–Judith Chettle, Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Danticat’s beautiful prose reads as though you’re sitting at her knee, hearing a favorite story told again. Warm and inviting, she makes Haiti seem like a second home to the reader. That’s not to say Danticat waxes sentimental. Full of controlled anger and grief, the author strips her family’s history bare.”

–Beth Dugan, Time Out Chicago

“Danticat pieces together the dreams of her father and uncle, devoted brothers living worlds apart, in politically volatile Haiti and in America, the promised land. With the subtlest understanding of how families can splinter but still cohere, she relives the shock of separation, first when her mother and father emigrated to New York, leaving 4-year-old Edwidge and her brother behind, and again, eight years later, when they took the children back from the aunt and uncle who had become second parents. With a storyteller’s magnetic force, Danticat draws readers to the streets of Haiti, where cutthroat gangs and looters destroyed her uncle’s church; to the hellish holding pen whe...

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurAlfred a Knopf Inc

- Date d'édition2007

- ISBN 10 1400041155

- ISBN 13 9781400041152

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages272

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 2,99

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

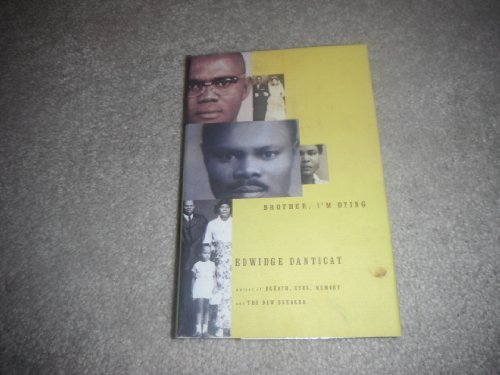

Brother, I'm Dying

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Buy for Great customer experience. N° de réf. du vendeur GoldenDragon1400041155

Brother, I'm Dying

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard1400041155

Brother, I'm Dying

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think1400041155

Brother, I'm Dying

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover1400041155

Brother, I'm Dying

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_1400041155

Brother, I'm Dying

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur Abebooks453641

Brother, I'm Dying

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Brand New Copy. N° de réf. du vendeur BBB_new1400041155

Brother I'm Dying (Signed First Edition)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Etat de la jaquette : New. 1st Edition. First printing. SIGNED BY AUTHOR on title page, her name only. A very fine/very fine copy in all respects, pristine and unread. This book was purchased new and opened only or the author to sign. Smoke-free. Shipped in well padded box. Nominated for National Book Award in Nonfiction, 2007. Winner, National Book Critics Circle Award, Nonfiction, 2008. LIT-D. Signed by Author(s). N° de réf. du vendeur PP0907-16

BROTHER, I'M DYING

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.01. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-1400041155