Articles liés à Train Your Mind: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary...

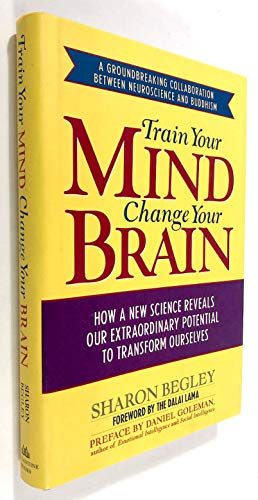

Train Your Mind: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves - Couverture rigide

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Can We Change?

Challenging the Dogma of the Hardwired Brain The northern Indian district of Dharamsala is composed of two towns, lower Dharamsala and upper. The mist-veiled peaks of the Dhauladhar (“white ridge”) range hug the towns like the bolster on a giant’s bed, while the Kangra Valley, described by a British colonial official as “a picture of rural loveliness and repose,” stretches into the distance. Upper Dharamsala is also known as McLeod Ganj. Founded as a hill station in the nineteenth century during the days of British colonial rule, the bustling hamlet (named after Britain’s lieutenant governor of Punjab at the time, David McLeod) is built on a ridge, where hiking the steep dirt path from one guesthouse to another requires the sure-footedness of a goat and astute enough planning that you don’t make the ankle-turning trek after dark and risk tumbling into a ravine.

Cows amble through intersections where street peddlers squat behind cloths piled with vegetables and grains, and taxis play a game of chicken with oncoming traffic, seeing who will lose his manhood first by edging his car out of the single lane of the town’s only real thoroughfare. The road curves past beggars and holy men who wear little but a loincloth and look as if they have not eaten since last week, yet whose many woes are neatly listed on a computer printout that they hopefully thrust at any passerby who slows even half a pace. Barefoot children dart out of nowhere at the sight of a Westerner and plead, “Please, madam, hungry baby, hungry baby,” pointing vaguely toward the open-air stalls that line the road.

From the flagstoned terrace of Chonor House, one of the guesthouses, all of Dharamsala spreads out before you. As soon as the sun is up, the maroon-robed monks are scurrying to prayers and the holy men crouched in back alleys are chanting om mani padme hum (“hail to jewel in the lotus”). Prayer scarves fluttering from boughs carry the Tibetan words May all sentient beings be happy and free from suffering. The prayers are supposed to be carried by the wind, and when you see them, you think, Wherever the wind blows, may those they touch find freedom from their pain.

Although lower Dharamsala is inhabited mostly by Indians, residents of McLeod Ganj are almost all Tibetan (with a sprinkling of Western expatriates and spiritual tourists), refugees who followed Tenzin Gyatso, the fourteenth Dalai Lama, into exile. Many of those remaining in Tibet, unable to flee themselves, have their toddlers and even infants smuggled across the border to Dharamsala, where they are cared for and educated at the Tibetan Children’s Village ten minutes above the town. For the parents, the price of ensuring that their children are educated in Tibetan culture and history, thus keeping their nation’s traditions and identity from being erased by the Chinese occupation, is never seeing their sons and daughters again.

McLeod Ganj has been the Dalai Lama’s home in exile and the headquarters of the Tibetan government in exile since 1959, when he escaped ahead of Chinese Communist troops, which had invaded Tibet eight years earlier. His compound, just off the main intersection where buses turn around and taxis wait for fares, is protected around the clock by Indian troops toting machine guns. The entrance is a tiny hut whose physical presence is as humble as the guards are thorough. From its anteroom, large enough for only a small sofa, dog-eared publications in a wooden rack, and a small coffee table, you pass through a door into the security room, where you place everything you want to bring in (bags, notebooks, cameras, tape recorders) on the X-ray belt before entering a closet-size booth, curtained at both ends, for the requisite pat-down by Tibetan guards.

Once cleared, you amble up an inclined asphalt path that winds past more Indian security guards draped with submachine guns and lounging in the shade. The sprawling grounds are forested with pines and rhododendrons; ceramic pots spilling purple bougainvillea and saffron marigolds surround the widely spaced buildings. The first structure to your right is a one-story building that houses the Dalai Lama’s audience chamber, also guarded by an Indian soldier with an automatic weapon. Just beyond is the Tibetan library and archives, and farther up the hill, the Dalai Lama’s two-story private compound, where he sleeps, meditates, and takes most of his meals. The large structure to the left is the old palace where the Dalai Lama lived before his current residence was built. Mostly used for ordinations, for the next five days its large main room will be the setting for an extraordinary meeting. Brought together by the Mind and Life Institute in October 2004, leading scholars from both the Buddhist and the Western scientific traditions will grapple with a question that has consumed philosophers and scientists for centuries: does the brain have the ability to change, and what is the power of the mind to change it?

Hardwired Dogma

Just a few years before, neuroscientists would not even have been part of this conversation, for textbooks, science courses, and cutting-edge research papers all hewed to the same line, as they had for almost as long as there had been a science of the brain.

No less a personage than William James, the father of experimental psychology in the United States, first introduced the word plasticity to the science of the brain, positing in 1890 that “organic matter, especially nervous tissue, seems endowed with a very extraordinary degree of plasticity.” By that, he meant “a structure weak enough to yield to an influence.” But James was “only” a psychologist, not a neurologist (there was no such thing as a neuroscientist a century ago), and his speculation went nowhere. Much more influential was the view expressed succinctly in 1913 by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the great Spanish neuroanatomist who had won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine seven years earlier. Near the conclusion of his treatise on the nervous system, he declared, “In the adult centers the nerve paths are something fixed, ended and immutable.” His gloomy assessment that the circuits of the living brain are unchanging, its structures and organization almost as static and stationary as a deathly white cadaver brain floating in a vat of formaldehyde, remained the prevailing dogma in neuroscience for almost a century. The textbook wis- dom held that the adult brain is hardwired, fixed in form and function, so that by the time we reach adulthood, we are pretty much stuck with what we have.

Conventional wisdom in neuroscience held that the adult mammalian brain is fixed in two respects: no new neurons are born in it, and the functions of the structures that make it up are immutable, so that if genes and development dictate that this cluster of neurons will process signals from the eye, and this cluster will move the fingers of the right hand, then by god they’ll do that and nothing else come hell or high water. There was good reason why all those extravagantly illustrated brain books show the function, size, and location of the brain’s structures in permanent ink. As late as 1999, neurologists writing in the prestigious journal Science admitted, “We are still taught that the fully mature brain lacks the intrinsic mechanisms needed to replenish neurons and reestablish neuronal networks after acute injury or in response to the insidious loss of neurons seen in neurodegen- erative diseases.”

That is not to say that scientists failed to recognize that the brain must undergo some changes throughout life. After all, since the brain is the organ of behavior and the repository of learning and memory, when we acquire new knowledge or master a new skill or file away the remembrance of things past, the brain changes in some real, physical way to make that happen. Indeed, researchers have known for decades that learning and memory find their physiological expression in the formation of new synapses (points of connection between neurons) and the strengthening of existing ones; in 2000, the wise men of Stockholm even awarded a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of the molecular underpinnings of memory.

But the changes underlying learning and memory are of the retail variety—strengthening a few synapses here and there or sprouting a few extra dendrites so neurons can talk to more of their neighbors, like a household getting an extra phone line. Wholesale changes, such as expanding a region that is in charge of a particular mental function or altering the wiring that connects one region to another, were deemed impossible.

Also impossible was for the basic layout of the brain to deviate one iota from the authoritative diagrams in anatomy textbooks: the visual cortex in the back was hardwired to handle the sense of sight, the somatosensory cortex curving along the top of the brain was hardwired to process tactile sensations, the motor cortex was hardwired to devote a precise amount of neural real estate to each muscle, and the auditory cortex was hardwired to field transmissions from the ears. Enshrined from clinical practice to scholarly monographs, this principle held that in contrast to the ability of the developing brain to change in significant ways, the adult brain is fixed, immutable. It has lost the capacity called neuroplasticity, the ability to change its structures and functions in a fundamental way.

To some extent, the dogma was understandable. For one thing, the human brain is made up of so many neurons and so many connections—an estimated 100 billion neurons making a total of some 100 trillion connections—that changing it even slightly looked like a risky undertaking, on a par with opening up the hard drive of a supercomputer and tinkering with a circuit or two on the motherboard. Surely that was not the sort of thing nature would permit and, in fact, something she might take steps to prevent. But there was a subtler issue. The brain contains the physical embodiment of personality and knowledge, character and emotions, memories and beliefs. Even allowing for the acquisition of knowledge and memories over a lifetime, and for the maturation of personality and character, it did not seem reasonable that the brain could or would change in any significant way. Neuroscientist Fred Gage, one of the researchers invited by the Dalai Lama to discuss the implications of neuroplasticity with him and other Buddhist scholars at the 2004 meeting, put the objections to the idea of a changing brain this way: “If the brain was changeable, then we would change. And if the brain made wrong changes, then we would change incorrectly. It was easier to believe there were no changes. That way, the individual would remain pretty much fixed.”

The doctrine of the unchanging human brain has had profound ramifications, none of them very optimistic. It led neurologists to assume that rehabilitation for adults who had suffered brain damage from a stroke was almost certainly a waste of time. It suggested that trying to alter the pathological brain wiring that underlies psychiatric diseases, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and depression, was a fool’s errand. And it implied that other brain-based fixities, such as the happiness “set point” to which a person returns after the deepest tragedy or the greatest joy, are as unalterable as Earth’s orbit.

But the dogma is wrong. In the last years of the twentieth century, a few iconoclastic neuroscientists challenged the paradigm that the adult brain cannot change and made discovery after discovery that, to the contrary, it retains stunning powers of neuroplasticity. The brain can indeed be rewired. It can expand the area that is wired to move the fingers, forging new connections that underpin the dexterity of an accomplished violinist. It can activate long-dormant wires and run new cables like an electrician bringing an old house up to code, so that regions that once saw can instead feel or hear. It can quiet circuits that once crackled with the aberrant activity that characterizes depression and cut pathological connections that keep the brain in the oh-god-something-is-wrong state that marks obsessive-compulsive disorder. The adult brain, in short, retains much of the plasticity of the developing brain, including the power to repair damaged regions, to grow new neurons, to rezone regions that performed one task and have them assume a new task, to change the circuitry that weaves neurons into the networks that allow us to remember, feel, suffer, think, imagine, and dream. Yes, the brain of a child is remarkably malleable. But contrary to Ramón y Cajal and most neuroscientists since, the brain can change its physical structure and its wiring long into adulthood.

The revolution in our understanding of the brain’s capacity to change well into adulthood does not end with the fact that the brain can and does change. Equally revolutionary is the discovery of how the brain changes. The actions we take can literally expand or contract different regions of the brain, pour more juice into quiet circuits and damp down activity in buzzing ones. The brain devotes more cortical real estate to functions that its owner uses more frequently and shrinks the space devoted to activities rarely performed. That’s why the brains of violinists devote more space to the region that controls the digits of the fingering hand. In response to the actions and experiences of its owner, a brain forges stronger connections in circuits that underlie one behavior or thought and weakens the connections in others. Most of this happens because of what we do and what we experience of the outside world. In this sense, the very structure of our brain—the relative size of different regions, the strength of connections between one area and another—reflects the lives we have led. Like sand on a beach, the brain bears the footprints of the decisions we have made, the skills we have learned, the actions we have taken. But there are also hints that mind-sculpting can occur with no input from the outside world. That is, the brain can change as a result of the thoughts we have thought.

A few findings suggest that brain changes can be generated by pure mental activity: merely thinking about playing the piano leads to a measurable, physical change in the brain’s motor cortex, and thinking about thoughts in certain ways can restore mental health. By willfully treating invasive urges and compulsions as errant neurochemistry—rather than as truthful messages that something is amiss—patients with OCD have altered the activity of the brain region that generates the OCD thoughts, for instance. By thinking differently about the thoughts that threaten to send them back into the abyss of despair, patients with depression have dialed up activity in one region of the brain and quieted it in another, reducing their risk of relapse. Something as seemingly insubstantial as a thought has the ability to act back on the very stuff of the brain, altering neuronal connections in a way that can lead to recovery from mental illness and perhaps to a greater capacity for empathy and compassion.

It is this aspect of neuroplasticity—research showing that the answer to the question of whether we can change is an emphatic yes—that brought five scientists to Dharamsala this autumn week. Since 1987, the Dalai Lama had opened his home once a year to weeklong “dialogues” with a handpicked group of scientists, to discuss dreams or emotions, consciousness or genetics or quantum physics. The format is simple. Each morning, one of the five invited scientists sits in an armchair beside the Dalai Lama at the front of the room used for ordinations and describes his or her work to him and the assembled guests—in ...

—Robert Sapolsky, author of Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers

“Reading this book is like opening doors in the mind. Sharon Begley brings the reader right to the intersection of scientific and meditative understanding, a place of exciting potential for personal and global transformation. And she does it so skillfully as to seem effortless.”

--Sharon Salzberg, author of Faith: Trusting Your Own Deepest Experience

“It is very seldom that a science in its infancy is so skillfully unpacked that it reads like a detective novel. The fact that this science includes collaborative efforts of neuroscientists, psychologists, contemplatives, philosophers, and the full engagement of the genius of the Dalai Lama is not only fascinating, but uplifting and inspiring. This book lets you know that how you pay attention to your experience can change your entire way of being.”

--Jon Kabat-Zinn, author of Coming to Our Senses

“I have meditated for 40 years, and have long felt that the potential of mind training to improve our emotional, physical and spiritual well-being has barely been tapped. Thanks to Sharon Begley’s fascinating book, though, that is about to change. As human beings, we really do have inner powers that can make a world of difference, particularly if our goal is not merely to advance our own agendas, but to cultivate compassion for the benefit of all living beings.”

--John Robbins, author of Healthy at 100, and Diet For a New America

“This is a truly illuminating and eminently readable book on the revolutionary new insights in mind sciences. I recommend it highly to anyone interested in understanding human potential.”

--Jack Kornfield, author of A Path with Heart

From the Hardcover edition.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurBallantine Books

- Date d'édition2007

- ISBN 10 1400063906

- ISBN 13 9781400063901

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Nombre de pages283

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 4,67

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves

Description du livre hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 230905155

Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur mon0000152968

Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_1400063906

Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves

Description du livre Etat : New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. N° de réf. du vendeur bk1400063906xvz189zvxnew

Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves

Description du livre hardcover. Etat : New. Well packaged and promptly shipped from California. Partnered with Friends of the Library since 2010. N° de réf. du vendeur 1LAA3T001MRK

Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves

Description du livre Etat : New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-1400063906-new

Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard1400063906

Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think1400063906

Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover1400063906

Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : Brand New. 1st edition. 283 pages. 9.75x6.25x1.25 inches. In Stock. N° de réf. du vendeur 1400063906