Articles liés à An Invisible Thread: The True Story of an 11-Year-Old...

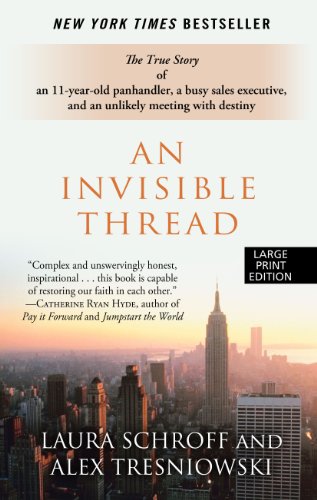

An Invisible Thread: The True Story of an 11-Year-Old Panhandler, A Busy Sales Executive, And An Unlikely Meeting With Destiny - Couverture rigide

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

The boy is stuck in something like hell. He is six years old and covered in small red bites from chinches—bedbugs—and he is woefully skinny due to an unchecked case of ringworm. He is so hungry his stomach hurts, but then being hungry is nothing new to him. When he was two years old the pangs got so bad he rooted through the trash and ate rat droppings and had to have his stomach pumped. He is staying in his father’s cramped, filthy apartment in a desolate stretch of Brooklyn, sleeping with stepbrothers who wet the bed, surviving in a place that smells like death. He has not seen his mother in three months, and he doesn’t know why. His world is a world of drugs and violence and unrelenting chaos, and he has the wisdom to know, even at six, that if something does not change for him soon, he might not make it.

He does not pray, does not know how, but he thinks, Please don’t let my father let me die. And this thought, in a way, is its own little prayer.

And then the boy sees his father come up the block, and the woman with the hammer sees him too, and she screams, “Junebug, where is my son?!”

The boy recognizes this voice, and he says, “Mom?”

The woman with the hammer looks down at the boy, and she looks puzzled, until she looks harder and finally says, “Maurice?”

The boy didn’t recognize his mother because her teeth had fallen out from smoking dope.

The mother didn’t recognize her son because he was shriveled from the ringworm.

Now she is chasing Junebug and yelling, “Look what you did to my baby!”

The boy should be frightened, or confused, but more than anything what the boy feels is happiness. He is happy that his mother has come back to get him, and because of that he is not going to die—at least not now, at least not in this place.

He will remember this as the moment when he knew his mother loved him.

© 2011 Laura Schroff|An Invisible Thread

“Excuse me, lady, do you have any spare change?”

This was the first thing he said to me, on 56th Street in New York City, right around the corner from Broadway, on a sunny September day.

And when I heard him, I didn’t really hear him. His words were part of the clatter, like a car horn or someone yelling for a cab. They were, you could say, just noise—the kind of nuisance New Yorkers learn to tune out. So I walked right by him, as if he wasn’t there.

But then, just a few yards past him, I stopped.

And then—and I’m still not sure why I did this—I came back.

I came back and I looked at him, and I realized he was just a boy. Earlier, out of the corner of my eye, I had noticed he was young. But now, looking at him, I saw that he was a child—tiny body, sticks for arms, big round eyes. He wore a burgundy sweatshirt that was smudged and frayed and ratty burgundy sweatpants to match. He had scuffed white sneakers with untied laces, and his fingernails were dirty. But his eyes were bright and there was a general sweetness about him. He was, I would soon learn, eleven years old.

He stretched his palm toward me, and he asked again, “Excuse me, lady, do you have any spare change? I am hungry.”

What I said in response may have surprised him, but it really shocked me.

“If you’re hungry,” I said, “I’ll take you to McDonald’s and buy you lunch.”

“Can I have a cheeseburger?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said.

“How about a Big Mac?”

“That’s okay, too.”

“How about a Diet Coke?”

“Yes, that’s okay.”

“Well, how about a thick chocolate shake and French fries?”

I told him he could have anything he wanted. And then I asked him if I could join him for lunch.

He thought about it for a second.

“Sure,” he finally said.

We had lunch together that day, at McDonald’s.

And after that, we got together every Monday.

For the next 150 Mondays.

His name is Maurice, and he changed my life.

Why did I stop and go back to Maurice? It is easier for me to tell you why I ignored him in the first place. I ignored him, very simply, because he wasn’t in my schedule.

You see, I am a woman whose life runs on schedules. I make appointments, I fill slots, I micromanage the clock. I bounce around from meeting to meeting, ticking things off a list. I am not merely punctual; I am fifteen minutes early for any and every engagement. This is how I live; it is who I am—but some things in life do not fit neatly into a schedule.

Rain, for example. On the day I met Maurice—September 1, 1986—a huge storm swept over the city, and I awoke to darkness and hammering rain. It was Labor Day weekend and the summer was slipping away, but I had tickets to the U.S. Open tennis tournament that afternoon—box seats, three rows from center court. I wasn’t a big tennis fan, but I loved having such great seats; to me, the tickets were tangible evidence of how successful I’d become. In 1986 I was thirty-five years old and an advertising sales executive for USA Today, and I was very good at what I did, which was building relationships through sheer force of personality. Maybe I wasn’t exactly where I wanted to be in my life—after all, I was still single, and another summer had come and gone without me finding that someone special—but by any standard I was doing pretty well. Taking clients to the Open and sitting courtside for free was just another measure of how far this girl from a working-class Long Island town had come.

But then the rains washed out the day, and by noon the Open had been postponed. I puttered around my apartment, tidied up a bit, made some calls, and read the paper until the rain finally let up in mid-afternoon. I grabbed a sweater and dashed out for a walk. I may not have had a destination, but I had a definite purpose—to enjoy the fall chill in the air and the peeking sun on my face, to get a little exercise, to say good-bye to summer. Stopping was never part of the plan.

And so, when Maurice spoke to me, I just kept going. Another thing to remember is that this was New York in the 1980s, a time when vagrants and panhandlers were as common a sight in the city as kids on bikes or moms with strollers. The nation was enjoying an economic boom, and on Wall Street new millionaires were minted every day. But the flip side was a widening gap between the rich and the poor, and nowhere was this more evident than on the streets of New York City. Whatever wealth was supposed to trickle down to the middle class did not come close to reaching the city’s poorest, most desperate people, and for many of them the only recourse was living on the streets. After a while you got used to the sight of them—hard, gaunt men and sad, haunted women, wearing rags, camped on corners, sleeping on grates, asking for change. It is tough to imagine anyone could see them and not feel deeply moved by their plight. Yet they were just so prevalent that most people made an almost subconscious decision to simply look the other way—to, basically, ignore them. The problem seemed so vast, so endemic, that stopping to help a single panhandler could feel all but pointless. And so we swept past them every day, great waves of us going on with our lives and accepting that there was nothing we could really do to help.

There had been one homeless man I briefly came to know the winter before I met Maurice. His name was Stan, and he lived on the street off Sixth Avenue, not far from my apartment. Stan was a stocky guy in his midforties who owned a pair of wool gloves, a navy blue skullcap, old work shoes, and a few other things stuffed into plastic shopping bags, certainly not any of the simple creature comforts we take for granted—a warm blanket, for instance, or a winter coat. He slept on a subway grate, and the steam from the trains kept him alive.

One day I asked if he’d like a cup of coffee, and he answered that he would, with milk and four sugars, please. And it became part of my routine to bring him a cup of coffee on the way to work. I’d ask Stan how he was doing and I’d wish him good luck, until one morning he was gone and the grate was just a grate again, not Stan’s spot. And just like that he vanished from my life, without a hint of what happened to him. I felt sad that he was no longer there and I often wondered what became of him, but I went on with my life and over time I stopped thinking about Stan. I hate to believe my compassion for him and others like him was a casual thing, but if I’m really honest with myself, I’d have to say that it was. I cared, but I didn’t care enough to make a real change in my life to help. I was not some heroic do-gooder. I learned, like most New Yorkers, to tune out the nuisance.

Then came Maurice. I walked past him to the corner, onto Broadway, and, halfway to the other side in the middle of the avenue, just stopped. I stood there for a few moments, in front of cars waiting for the light to change, until a horn sounded and startled me. I turned around and hustled back to the sidewalk. I don’t remember thinking about it or even making a conscious decision to turn around. I just remember doing it.

Looking back all these years later, I believe there was a strong, unseen connection that pulled me back to Maurice. It’s something I call an invisible thread. It is, as the old Chinese proverb tells us, something that connects two people who are destined to meet, regardless of time and place and circumstance. Some legends call it the red string of fate; others, the thread of destiny. It is, I believe, what brought Maurice and I to the same stretch of sidewalk in a vast, teeming city—just two people out of eight million, somehow connected, somehow meant to be friends.

Look, neither of us is a superhero, nor even especially virtuous. When we met we were just two people with complicated pasts and fragile dreams. But somehow we found each other, and we became friends.

And that, you will see, made all the difference for us both.|An Invisible Thread

We walked across the avenue to the McDonald’s, and for the first few moments neither of us spoke. This thing we were doing—going to lunch, a couple of strangers, an adult and a child—it was weird, and we both felt it.

Finally, I said, “Hi, I’m Laura.”

“I’m Maurice,” he said.

We got in line and I ordered the meal he’d asked for—Big Mac, fries, thick chocolate shake—and I got the same for myself. We found a table and sat down, and Maurice tore into his food. He’s famished, I thought. Maybe he doesn’t know when he will eat again. It took him just a few minutes to pack it all away. When he was done, he asked where I lived. We were sitting by the side window and could see my apartment building, the Symphony, from our table, so I pointed and said, “Right there.”

“Do you live in a hotel, too?” he asked.

“No,” I said, “it’s an apartment.”

“Like the Jeffersons?”

“Oh, the TV show. Not as big. It’s just a studio. Where do you live?”

He hesitated for a moment before telling me he lived at the Bryant, a welfare hotel on West 54th Street and Broadway.

I couldn’t believe he lived just two blocks from my apartment. One street was all that separated our worlds.

I would later learn that the simple act of telling me where he lived was a leap of faith for Maurice. He was not in the habit of trusting adults, much less white adults. If I had thought about it I might have realized no one had ever stopped to talk to him, or asked him where he lived, or been nice to him, or bought him lunch. Why wouldn’t he be suspicious of me? How could he be sure I wasn’t a Social Services worker trying to take him away from his family? When he went home later and told one of his uncles some woman had taken him to McDonald’s, the uncle said, “She is trying to snatch you. Stay away from her. Stay off that corner, in case she comes back.”

I figured I should tell Maurice something about myself. Part of me felt that taking him to lunch was a good thing to do, but another part wasn’t entirely comfortable with it. After all, he was a child and I was a stranger, and hadn’t children everywhere been taught not to follow strangers? Was I crossing some line here? I imagine some will say what I did was flat-out wrong. All I can say is, in my heart, I believe it was the only thing I could have done in that situation. Still, I understand how people might be skeptical. So I figured if I told him something about myself, I wouldn’t be such a stranger.

“I work at USA Today,” I said.

I could tell he had no idea what that meant. I explained it was a newspaper, and that it was new, and that we were trying to be the first national newspaper in the country. I told him my job was selling advertising, which was how the newspaper paid for itself. None of this cleared things up.

“What do you do all day?” he asked.

Ah, he wanted to know my schedule. I ran through it for him—sales calls, meetings, working lunches, presentations, sometimes client dinners.

“Every day?”

“Yes, every day.”

“Do you ever miss a day?”

“If I’m sick,” I said. “But I’m rarely sick.”

“But you never just not do it one day?”

“No, never. That’s my job. And besides, I really like what I do.”

Maurice could barely grasp what I was saying. Only later would I learn that until he got to know me, he had never known anyone with a job.

There was something else I didn’t know about Maurice as I sat across from him that day. I didn’t know that in the pocket of his sweatpants he had a knife.

Not a knife, actually, but a small razor-blade box cutter. He had stolen it from a Duane Reade on Broadway. It was a measure of my inability to fathom his world that I never thought for a single moment he might be carrying a weapon. The idea of a weapon in his delicate little hands was incomprehensible to me. It never dawned on me that he could even use one, much less that he might truly need one to protect himself from the violence that permeated his life.

For a good part of Maurice’s childhood, the greatest harm he faced came from the man who gave him life.

Maurice’s father wasn’t around for very long, but in that short time he was an inordinately damaging presence—an out-of-control buzz saw you couldn’t shut off. He was also named Maurice, after his own absentee dad, but when he was born no one knew how to spell it so he became Morris. It wasn’t long before most people called him Lefty anyway, because, although he was right-handed, it was his left that he used to knock people out.

Morris was just five foot two, but his size only made him tougher, more aggressive, as if he had something to prove every minute of every day. In the notoriously dangerous east Brooklyn neighborhood where he lived—a one-square-mile tract known as Brownsville, birthplace of the nefarious 1940s gang Murder Inc. and later home to some of the roughest street gangs in the country—Morris was one of...

“Excuse me lady, do you have any spare change? I am hungry.”

When I heard him, I didn’t really hear him. His words were part of the clatter, like a car horn or someone yelling for a cab. They were, you could say, just noise—the kind of nuisance New Yorkers learn to tune out. So I walked right by him, as if he wasn’t there.

But then, just a few yards past him, I stopped.

And then—and I’m still not sure why I did this—I came back.

When Laura Schroff first met Maurice on a New York City street corner, she had no idea that she was standing on the brink of an incredible and unlikely friendship that would inevitably change both their lives. As one lunch at McDonald’s with Maurice turns into two, then into a weekly occurrence that is fast growing into an inexplicable connection, Laura learns heart-wrenching details about Maurice’s horrific childhood.

The boy is stuck in something like hell. He is six years old and covered in small red bites from chinches—bed bugs—and he is woefully skinny due to an unchecked case of ringworm. He is so hungry his stomach hurts, but then he is used to being hungry: when he was two years old the pangs got so bad he rooted through the trash and ate rat droppings. He had to have his stomach pumped. He is staying in his father’s cramped, filthy apartment, sleeping with stepbrothers who wet the bed, surviving in a place that smells like something died. He has not seen his mother in three months, and he doesn’t know why. His world is a world of drugs and violence and unrelenting chaos, and he has the wisdom to know, even at six, that if something does not change for him soon, he might not make it.

Sprinkled throughout the book is also Laura’s own story of her turbulent childhood. Every now and then, something about Maurice's struggles reminds her of her past, how her father’s alcohol-induced rages shaped the person she became and, in a way, led her to Maurice.

He started by cursing my mother and screaming at her in front of all of us. My mother pulled us closer to her and waited for it to pass. But it didn’t. My father left the room and came back with two full liquor bottles. He threw them right over our heads, and they smashed against the wall. Liquor and glass rained down on us, and we pulled up the covers to shield ourselves. My father hurled the next bottle, and then went back for two more. They shattered just above our heads; the sound was sickening. My father kept screaming and ranting, worse than I’d ever heard him before. When he ran out of bottles he went into the kitchen and overturned the table and smashed the chairs. Just then the phone rang, and my mother rushed to get it. I heard her screaming to the caller to get help. My father grabbed the phone from her and ripped the base right out of the wall. My mother ran back to us as my father kept kicking and throwing furniture, unstoppable, out of his mind.

As their friendship grows, Laura offers Maurice simple experiences he comes to treasure: learning how to set a table, trimming a Christmas tree, visiting her nieces and nephew on Long Island, and even having homemade lunches to bring to school.

“If you make me lunch,” he said, “will you put it in a brown paper bag?”

I didn’t really understand the question. "Okay, sure. But why do you want it in a brown paper bag?”

“Because when I see kids come to school with their lunch in a brown paper bag, that means someone cares about them.”

I looked away when Maurice said that, so he wouldn’t see me tear up. A simple brown paper bag, I thought.

To me, it meant nothing. To him, it was everything.

It is the heartwarming story of a friendship that has spanned thirty years, that brought life to an over-scheduled professional who had lost sight of family and happiness and hope to a hungry and desperate boy whose family background in drugs and crime and squalor seemed an inescapable fate.

He had, inside of him, some miraculous reserve of goodness and strength, some fierce will to be special. I saw this in his hopeful face the day he asked for spare change, and I see it in his eyes today. Whatever made me notice him on that street corner so many years ago is clearly something that cannot be extinguished, no matter how relentless the forces aligned against it. Some may call it spirit. Some might call it heart. Whatever it was, it drew me to him, as if we were bound by some invisible, unbreakable thread.

And whatever it is, it binds us still.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurWheeler Pub Inc

- Date d'édition2012

- ISBN 10 1410447863

- ISBN 13 9781410447869

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages363

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,74

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

An Invisible Thread: The True Story of an 11-Year-Old Panhandler, a Busy Sales Executive, and an Unlikely Meeting with Destiny (Wheeler Large Print Book Series)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_1410447863

An Invisible Thread: The True Story of an 11-Year-Old Panhandler, a Busy Sales Executive, and an Unlikely Meeting with Destiny (Wheeler Large Print Book Series)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard1410447863

An Invisible Thread: The True Story of an 11-Year-Old Panhandler, a Busy Sales Executive, and an Unlikely Meeting with Destiny (Wheeler Large Print Book Series)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think1410447863

An Invisible Thread: The True Story of an 11-Year-Old Panhandler, a Busy Sales Executive, and an Unlikely Meeting with Destiny (Wheeler Large Print Book Series)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. New. book. N° de réf. du vendeur D8S0-3-M-1410447863-6

An Invisible Thread: The True Story of an 11-Year-Old Panhandler, a Busy Sales Executive, and an Unlikely Meeting with Destiny (Wheeler Large Print Book Series)

Description du livre Etat : New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. N° de réf. du vendeur bk1410447863xvz189zvxnew