Articles liés à Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

On the eve of my twenty-fourth birthday I interview my mother. We meet at a vegetarian restaurant in Manhattan, one that announces itself as organic and farm-fresh, and despite my recent penchant for all things pork and shellfish, I am looking forward to the simplicity the meal promises. The waiter who serves us is conspicuously gentile-looking, with scruffy blond hair and big blue eyes. He treats us like royalty because we are on the Upper East Side and are prepared to shell out a hundred bucks for a lunch consisting largely of vegetables. I think it is ironic that he doesn’t know that the two of us are outsiders, that he automatically takes our existence for granted. I never thought this day would come.

Before we met, I told my mother that I had some questions for her. Although we’ve spent more time together over the past year than we did in all my teenage years put together, thus far I’ve mostly avoided talking about the past. Perhaps I did not want to know. Maybe I didn’t want to find out that whatever information had been fed to me about my mother was wrong, or maybe I didn’t want to accept that it was right. Still, publishing my life story calls for scrupulous honesty, and not just my own.

A year ago to this date I left the Hasidic community for good. I am twenty-four and I still have my whole life ahead of me. My son’s future is chock-full of possibilities. I feel as if I have made it to the starting line of a race just in time to hear the gun go off. Looking at my mother, I understand that there might be similarities between us, but the differences are more glaringly obvious. She was older when she left, and she didn’t take me with her. Her journey speaks more of a struggle for security than happiness. Our dreams hover above us like clouds, and mine seem bigger and fluffier than her wispy strip of cirrus high in a winter sky.

As far back as I can remember, I have always wanted everything from life, everything it can possibly give me. This desire separates me from people who are willing to settle for less. I cannot even comprehend how people’s desires can be small, their ambitions narrow and limited, when the possibilities are so endless. I do not know my mother well enough to understand her dreams; for all I know, they seem big and important to her, and I want to respect that. Surely, for all our differences, there is that thread of common ground, that choice we both made for the better.

My mother was born and raised in a German Jewish community in England. While her family was religious, they were not Hasidic. A child of divorce, she describes her young self as troubled, awkward, and unhappy. Her chances of marrying, let alone marrying well, were slim, she tells me. The waiter puts a plate of polenta fries and some black beans in front of her, and she shoves her fork in a fry.

When the choice of marrying my father came along, it seemed like a dream, she says between bites. His family was wealthy, and they were desperate to marry him off. He had siblings waiting for him to get engaged so that they could start their own lives. He was twenty-four, unthinkably old for a good Jewish boy, too old to be single. The older they get, the less likely they are to be married off. Rachel, my mother, was my father’s last shot.

Everyone in my mother’s life was thrilled for her, she remembers. She would get to go to America! They were offering a beautiful, brand-new apartment, fully furnished. They offered to pay for everything. She would receive beautiful clothes and jewelry. There were many sisters-in-law who were excited to become her friends.

“So they were nice to you?” I ask, referring to my aunts and uncles, who, I remember, mostly looked down on me for reasons I could never fully grasp.

“In the beginning, yes,” she says. “I was the new toy from England, you know. The thin, pretty girl with the funny accent.”

She saved them all, the younger ones. They were spared the fate of getting older in their singlehood. In the beginning, they were grateful to see their brother married off.

“I made him into a mensch,” my mother tells me. “I made sure he always looked neat. He couldn’t take care of himself, but I did. I made him look better; they didn’t have to be so ashamed of him anymore.”

Shame is all I can recall of my feelings for my father. When I knew him, he was always shabby and dirty, and his behavior was childlike and inappropriate.

“What do you think of my father now?” I ask. “What do you think is wrong with him?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Delusional, I suppose. Mentally ill.”

“Really? You think it’s all that? You don’t think he was just plain mentally retarded?”

“Well, he saw a psychiatrist once after we were married, and the psychiatrist told me he was pretty sure your father had some sort of personality disorder, but there was no way to tell, because your father refused to cooperate with further testing and never went back for treatment.”

“Well, I don’t know,” I say thoughtfully. “Aunt Chaya told me once that he was diagnosed as a child, with retardation. She said his IQ was sixty-six. There’s not much you can do about that.”

“They didn’t even try, though,” my mother insists. “They could have gotten him some treatment.”

I nod. “So in the beginning, they were nice to you. But what happened after?” I remember my aunts talking about my mother behind her back, saying hateful things.

“Well, after the fuss calmed down, they started to ignore me. They would do things and leave me out of it. They looked down on me because I was from a poor family, and they had all married money and come from money and they lived different lives. Your father couldn’t earn any money, and neither could I, so your grandfather supported us. But he was stingy, counting out the bare minimum for groceries. He was very smart, your zeide, but he didn’t understand people. He was out of touch with reality.”

I still feel a little sting when someone says something bad about my family, as if I have to defend them.

“Your bubbe, on the other hand, she had respect for me, I could tell. No one ever listened to her, and certainly she was more intelligent and open-minded than anyone gave her credit for.”

“Oh, I agree with that!” I’m thrilled to find we have some common ground, one family member whom we both see the same way. “She was like that to me too; she respected me even when everyone else thought I was just troublesome.”

“Yes, well . . . she had no power, though.”

“True.”

So in the end she had nothing to cling to, my mother. No husband, no family, no home. In college, she would exist, would have purpose, direction. You leave when there’s nothing left to stay for; you go where you can be useful, where people accept you.

The waiter comes to the table holding a chocolate brownie with a candle stuck in it. “Happy birthday to you . . . ,” he sings softly, meeting my eyes for a second. I look down, feeling my cheeks redden.

“Blow out the candle,” my mother urges, taking out her camera. I want to laugh. I bet the waiter thinks that I’m just like every other birthday girl going out with her mom, and that we do this every year. Would anyone guess that my mother missed most of my birthdays growing up? How can she be so quick to jump back into things? Does it feel natural to her? It certainly doesn’t feel that way to me.

After both of us have devoured the brownie, she pauses and wipes her mouth. She says that she wanted to take me with her, but she couldn’t. She had no money. My father’s family threatened to make her life miserable if she tried to take me away. Chaya, the oldest aunt, was the worst, she says. “I would visit you and she would treat me like garbage, like I wasn’t your mother, had never given birth to you. Who gave her the right, when she wasn’t even blood?” Chaya married the family’s oldest son and immediately took control of everything, my mother recalls. She always had to be the boss, arranging everything, asserting her opinions everywhere.

And when my mother left my father for good, Chaya took control of me too. She decided that I would live with my grandparents, that I would go to Satmar school, that I would marry a good Satmar boy from a religious family. It was Chaya who, in the end, taught me to take control of my own life, to become iron-fisted like she was, and not let anyone else force me to be unhappy.

It was Chaya who convinced Zeidy to talk to the matchmaker, I learned, even though I had only just turned seventeen. In essence, she was my matchmaker; she was the one who decided to whom I was to be married. I’d like to hold her responsible for everything I went through as a result, but I am too wise for that. I know the way of our world, and the way people get swept along in the powerful current of our age-old traditions.

August 2010

New York City

|Unorthodox 1

In Search of My Secret Power

Matilda longed for her parents to be good and loving and understanding and honourable and intelligent. The fact that they were none of those things was something she had to put up with. . . .

Being very small and very young, the only power Matilda had over anyone in her family was brainpower.

—From Matilda, by Roald Dahl

My father holds my hand as he fumbles with the keys to the warehouse. The streets are strangely empty and silent in this industrial section of Williamsburg. Above, the stars glow faintly in the night sky; nearby, occasional cars whoosh ghostlike along the expressway. I look down at my patent leather shoes tapping impatiently on the sidewalk and I bite my lip to stop the impulse. I’m grateful to be here. It’s not every week that Tatty takes me with him.

One of my father’s many odd jobs is turning the ovens on at Beigel’s kosher bakery when Shabbos is over. Every Jewish business must cease for the duration of the Shabbos, and the law requires that a Jew be the one to set things in motion again. My father easily qualifies for a job with such simple requirements. The gentile laborers are already working when he gets there, preparing the dough, shaping it into rolls and loaves, and when my father walks through the vast warehouse flipping the switches, a humming and whirring sound starts up and builds momentum as we move through the cavernous rooms. This is one of the weeks he takes me with him, and I find it exciting to be surrounded by all this hustle and know that my father is at the center of it, that these people must wait for him to arrive before business can go on as usual. I feel important just knowing that he is important too. The workers nod to him as he passes, smiling even if he is late, and they pat me on the head with powdery, gloved hands. By the time my father is done with the last section, the entire factory is pulsating with the sound of mixing machines and conveyor belts. The cement floor vibrates slightly beneath my feet. I watch the trays slide into the ovens and come out the other end with shiny golden rolls all in a row, as my father makes conversation with the workers while munching on an egg kichel.

Bubby loves egg kichel. We always bring her some after our trips to the bakery. In the front room of the warehouse there are shelves stocked with sealed and packed boxes of various baked goods ready to be shipped in the morning, and on our way out, we will take as many as we can carry. There are the famous kosher cupcakes with rainbow sprinkles on top; the loaves of babka, cinnamon- and chocolate-flavored; the seven-layer cake heavy with margarine; the mini black-and-white cookies that I only like to eat the chocolate part from. Whatever my father selects on his way out will get dropped off at my grandparents’ house later, dumped on the dining room table like bounty, and I will get to taste it all.

What can measure up to this kind of wealth, the abundance of sweets and confections scattered across a damask tablecloth like goods at an auction? Tonight I will fall easily into sleep with the taste of frosting still in the crevices of my teeth, crumbs melting into the pockets on either side of my mouth.

This is one of the few good moments I share with my father. Often he gives me very little reason to be proud of him. His shirts have yellow spots under the arms even though Bubby does most of his laundry, and his smile is too wide and silly, like a clown’s. When he comes to visit me at Bubby’s house, he brings me Klein’s ice cream bars dipped in chocolate and looks at me expectantly as I eat, waiting for my remarks of appreciation. This is being a father, he must think—supplying me with treats. Then he leaves as suddenly as he arrives, off on another one of his “errands.”

People employ him out of pity, I know. They hire him to drive them around, deliver packages, anything they think he is capable of doing without making mistakes. He doesn’t understand this; he thinks he is performing a valuable service.

My father performs many errands, but the only ones he allows me to participate in are the occasional trips to the bakery and the even rarer ones to the airport. The airport trips are more exciting, but they only happen a couple of times a year. I know it’s strange for me to enjoy visiting the airport itself, when I know I will never even get on a plane, but I find it thrilling to stand next to my father as he waits for the person he is supposed to pick up, watching the crowds hurrying to and fro with their luggage squealing loudly behind them, knowing that they are all going somewhere, purposefully. What a marvelous world this is, I think, where birds touch down briefly before magically reappearing at another airport somewhere halfway across the planet. If I had a wish, it would be to always be traveling, from one airport to another. To be freed from the prison of staying still.

After my father drops me off at the house, I might not see him again for a while, maybe weeks, unless I run into him on the street, and then I will hide my face and pretend not to see him, so that I don’t get called over and introduced to whomever he is speaking to. I can’t stand the looks of curious pity people give me when they find out I am his daughter.

“This is your maideleh?” they croon condescendingly, pinching my cheek or lifting my chin with a crooked finger. Then they peer at me closely, looking for some sign that I am indeed the offspring of this man, so they can later say, “Nebach, poor little soul, it’s her fault that she was born? In her face you can see it, she’s not all here.”

Bubby is the only person who thinks I’m one hundred percent all here. With her you can tell she never questions it. She doesn’t judge people. She never came to conclusions about my father either, but maybe that was just denial. When she tells stories of my father at my age, she paints him as lovably mischievous. He was always too skinny, so she would try anything to get him to eat. Whatever he wanted he got, but he couldn’t leave the table until his plate was empty. One time he tied his chicken drumstick to a piece of string and dangled it out the window to the cats in the yard so he wouldn’t have to stay stuck at the table for hours while everyone was outside playing. When Bubby came back, he showed her his empty plate and she asked, “Where are the bones? You can’t eat the bones too.” That’s how she knew.

I wanted to admire my father for his ingenious idea, but my bubble of pride burst when Bubby told me he ...

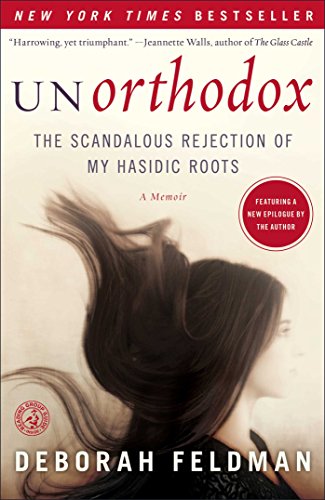

“Deborah Feldman was raised in an insular, oppressive world where she was taught that, as a woman, she wasn’t capable of independent thought. But she found the pluck and determination needed to make the break from that world and has written a brave, riveting account of her journey. Unorthodox is harrowing, yet triumphant.”—Jeannette Walls, #1 bestselling author of The Glass Castle and Half Broke Horses

“[Feldman’s] matter-of-fact style masks some penetrating insights.”—The New York Times

“An unprecedented view into a Hasidic community that few outsiders ever experience. . . . Unorthodox reminds us that there are religious communities in the United States that restrict young women to marriage and motherhood. These women are expected to be obedient to their community and religion, without question or complaint, no matter the price.”—Minneapolis Star-Tribune

“Riveting . . . extraordinary.”—Marie Claire

“Eloquent, appealing, and just emotional enough . . . No doubt girls all over Brooklyn are buying this book, hiding it under their mattresses, reading it after lights out—and contemplating, perhaps for the first time, their own escape.”—HuffingtonPost.com

“Deborah Feldman has stripped the cloak off the insular Satmar sect of Hasidic Judaism, offering outsiders a rare glimpse into the ultraconservative world in which she was raised.”—Globe and Mail (Toronto)

“Compulsively readable, Unorthodox relates a unique coming-of-age story that manages to speak personally to anyone who has ever felt like an outsider in her own life. Feldman bravely lays her soul bare, unflinchingly sharing intimate thoughts and ideas unthinkable within the deeply religious existence of the Satmars. . . . Teens will devour this candid, detailed memoir of an insular way of life so unlike that of the surrounding society.”—School Library Journal

“[Feldman’s] no-holds-barred memoir bookstores on February 14th. And it’s not exactly a Valentine to the insular world of shtreimels, sheitels and shtiebels. Instead, [Unorthodox] describes an oppressive community in which secular education is minimal, outsiders are feared and disdained, English-language books are forbidden, mental illness is left untreated, abuse and other crimes go unreported . . . a surprisingly moving, well-written and vivid coming-of-age tale.”—The Jewish Week

“Imagine Frank McCourt as a Jewish virgin, and you've got Unorthodox in a nutshell . . . a sensitive and memorable coming-of-age story.”—Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurSimon & Schuster

- Date d'édition2012

- ISBN 10 1439187010

- ISBN 13 9781439187012

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages272

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots by Feldman, Deborah [Paperback ]

Description du livre Soft Cover. Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur 9781439187012

Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur DADAX1439187010

Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots

Description du livre paperback. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur mon0000244665

Unorthodox The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots

Description du livre PAP. Etat : New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. N° de réf. du vendeur FS-9781439187012

Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots (Paperback or Softback)

Description du livre Paperback or Softback. Etat : New. Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots 0.5. Book. N° de réf. du vendeur BBS-9781439187012

Unorthodox Format: Paperback

Description du livre Etat : New. Brand New. N° de réf. du vendeur 1439187010

Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots

Description du livre Etat : New. This is a brand new book! Fast Shipping - Safe and Secure Mailer - Our goal is to deliver a better item than what you are hoping for! If not we will make it right!. N° de réf. du vendeur 1XGOUS00129V_ns

Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots

Description du livre Etat : New. Book is in NEW condition. N° de réf. du vendeur 1439187010-2-1

Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : New. Brand New!. N° de réf. du vendeur 1439187010

Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur ABLIING23Mar2411530275562