Articles liés à Plenty Ladylike: A Memoir

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBN

Extrait :

Plenty Ladylike CHAPTER ONE Blonde Ambition

Street after street, door after door, I walked and knocked. “Hello, I’m Claire McCaskill, and I’m an assistant prosecutor. I’m running for state representative, and I’d appreciate your vote.”

I was twenty-eight years old, single, a renter with no money or political organization backing me up. It was 1982, and I was a young prosecutor with courtroom experience who was comfortable making a case and doing hard work. When I ran for my first political office, a seat representing part of Kansas City in the Missouri House, people told me I needed to knock on doors. I knocked on 11,432 of them.

While I remember many of these encounters, one has replayed itself in my head hundreds of times over the years. It was dusk on an early summer evening as I approached a small Tudor in a modest neighborhood. I’d been knocking for several hours by the time I reached this house. A man in his upper-middle years opened the door, and I rattled off my greeting. He looked me over slowly, up and down, and said, “You’re too young. Your hair is too long. You’re a girl. No way are you tough enough for politics. Those politicians in Jeff City’d eat you alive. Go find yourself a husband.”

And he slammed the door in my face.

I won that race—and I kept on running for the next thirty years.

From a very young age, I was driven. In school I spoke up so much I earned the nickname “Motor-mouth McCaskill.” I didn’t want to just get A’s; I wanted to win every spelling contest. I didn’t want to be just a cheerleader; I wanted to be captain of the squad. Until I got to college I didn’t realize that such drive wasn’t always socially correct. My parents had done an amazing job of protecting me from a very dangerous point of view: that women should not be ambitious.

My mom, Betty Anne McCaskill, emphasized early on that women can do anything men can do. She refused to let me and my sisters, Anne and Lisa, get a Barbie, Queen of the Prom board game when we were young. To win the game you had to get a dress and a boyfriend and go steady. “Dumb game. That is not how you win anything,” she told us. While she never discouraged marriage, she and Dad both reinforced the need for us to first be self-sufficient. In that sense, my parents were way ahead of their time in stressing independence. My dad’s words still ring in my ears: “You can’t find happiness with someone else until you are happy with yourself.” My dad, Bill, gave me the gift of incredible respect for a sense of humor. Even while I was ambitious, the people in my household taught me not to take myself too seriously. And as the most important male figure in my life, my father also gave me permission to be bossy and opinionated.

When I was in high school, I encountered my first situation where I had to choose whether to go along and be popular or to speak out even though I risked alienating some of my friends. The social sorority to which I belonged had always used popularity as the only measure for inclusion. I took the risk of saying that it might be a good idea to look at grades and school activities and maybe work for a little diversity if we were really focused on service as much as prestige. I felt strongly about this, and it hurt when my friends turned against me. That evening, as I was crying in my room, Dad quietly told me to snap out of it. He asked me to choose whether I wanted to be a leader or a follower, pointing out that followers never got their feelings hurt, but leaders always do. He told me one of his corny jokes and made me laugh. That was the year that Dad gave me John F. Kennedy’s book Profiles in Courage for Christmas.

Each year Dad encouraged me to enter the American Legion speech contest at West Junior High School. Though I made the finals in seventh and eighth grade, I never won. The contest required memorization of the speech, no notes allowed. One of those years I had the traumatic experience of forgetting my speech in front of the entire student body. Part of me wanted to sit out the competition in ninth grade, but a bigger part wanted to win. Dad and I talked about it and decided that my topic for this last try needed to be something I felt strongly about. I chose to give a speech about the Ku Klux Klan. He had me research the KKK, and we decided together that their offensive and repugnant oath would be a dramatic beginning to the speech.

I can recall exactly how I felt standing alone at the podium, and I remember where Dad was sitting. And I can still feel the surge of adrenaline when, as I opened with those sickening words of allegiance to racism, I felt the connection with the audience and the incredible high when the thunderous applause came at the end of the speech, when I closed with the Pledge of Allegiance. Later Mom told me that when they announced me the winner, Dad was crying. It was probably around that time that I started talking about being Missouri’s first woman governor.

If you wanted to predict where I might end up, there are some good clues in a series of episodes that took place during my junior and senior years at Hickman High School in Columbia, Missouri. I had been a cheerleader all through junior high and until my senior year at Hickman, when they brought in professional judges to pick the team and I didn’t make it. It was as if the roof had fallen in on my life. My younger sister, Lisa, can still recall coming home and finding me sprawled across the bed, sobbing, mascara running down my face. What a comedown. What a catastrophe.

To make up for losing my cheerleader’s spot, I launched a secret comeback by running for Hickman’s homecoming queen. It was a stealth operation because nobody really “campaigned” for the honor. The football team chose the queen, usually the girlfriend of one of the team captains. I figured out that all the votes from the linemen and the second- and third-string players were being taken for granted, and I methodically identified all these players and their girlfriends. Then I quietly began to reach out to them. I paid them special attention, did favors, arranged dates, and went out of my way to show I cared. I did it subtly and slowly for months.

At first the plan was all about me. But I came to learn that I really liked the people whose votes I was courting. They became my friends, and I started to believe that I was actually giving them some input into a process they never had before. The following winter I wore the homecoming crown, and although I wanted others to believe I won because I was popular, in fact I had carried out an effective political operation by identifying a constituency and working hard to gain its support. For years afterward I kept to myself what I had done, talking about it only with my closest friends. I’m still slightly embarrassed to admit that I campaigned for homecoming queen, but it’s important for women to own being strategic. To this day I remain friends with some of those linemen on the football squad.

Losing my cheerleading spot helped me in the long run. The only salvation I could find at that time was when I became Pep Club president and, at my dad’s urging, joined the competitive speech and debate squad. I had to learn how to speak on any topic I was given only moments before walking into the room for the tournament. It was a frightening thing to do, but I remember hitting my stride during the third contest and thinking, I can do this. That confidence has come in handy countless times in the courtroom, on the campaign trail, and on the floor of the U.S. Senate. I soon discovered that other students were warming up to me now that I had been brought down a notch or two from my cheerleading pedestal. I realized vulnerability can be an asset.

The day after I graduated from Hickman High School, I packed my beat-up Chevy Nova—bought with money I made working as a clerk at a fabric store—and took off for a job bussing tables at the Lodge of Four Seasons at the Lake of the Ozarks. Every summer throughout college I worked as a waitress at the Lodge, located about an hour from Columbia and the University of Missouri. You learn a lot about people when you wait on them. You learn how to communicate and how to calm people down when they’re upset or frustrated, and you learn that giving people information in a friendly manner can produce great results. That is another important skill in politics.

Before I graduated from high school, I made up my mind that I was going to law school. I pursued a political science degree at the University of Missouri and concentrated on getting good grades. I set goals for myself, and I’d often lie awake at night plotting out how to achieve them. I considered each step that would be necessary in the process and identified allies. Sometimes my ambition surprised me. As a freshman I pledged one of the school’s most prestigious sororities. I was the first woman to chair the university’s homecoming gala. I became a football hostess, a job in which you help recruit athletes. While landing the hostess position depended partly on looks, you also had to know enough about football to answer their questions and show you understood the game. You had to know the difference between a tight end and a linebacker because when you’re meeting with a potential recruit it is important to make him feel welcomed and needed, and knowing about his job as a football player was part of that.

Many years later, Anne Loew, one of my sorority sisters, talked about how, though it might have looked easy, I had put a lot of work into getting to where I wanted to be. “We’d walk into a party and all I’d want to do was grab a beer and have some fun,” she said. “But then I’d notice Claire working the crowd. She seemed to have an unerring ability to single out the most important people in any group—whether students or professors—and concentrate on them. It was a challenge to her to win them over. It didn’t matter if they were her enemies. Claire would be there, smiling and chatting. ‘Why have an enemy,’ she’d say to me, ‘when you can have a friend?’ ”

Over time Anne learned that I was working on a long-term plan—that each step forward was getting me closer to a specific goal. Jill McDonald, another friend from those days, didn’t like me at first because I seemed a little too opinionated, a little too pushy. But later she came to see those traits as independence. “Despite her ambition, in some ways Claire really didn’t care what other people thought of her,” Jill said. “In her personal life, she did what she wanted. In that area she never compromised to achieve anything, and yet somehow she still came out all right, though there were people who came to hate her for that attitude. Back then there were still lots of men and women around campus who wanted her to be just another meek sorority type. Claire just said ‘to hell with them.’ ”

More valuable to me than my political science classes were the outside experiences that came with them. For example, in 1974, when I was a junior, I conducted research for one of my professors, David Leuthold, by attending the Democratic Midterm Convention in Kansas City. Warren Beatty was there as a delegate, and it was interesting to me to see how much more attention the movie star received than the well-known feminist icon Bella Abzug. One summer I took a comparative government course at Georgetown University and interned in the office of Congressman Jim Symington of Missouri. My most valuable learning experience outside the classroom came with an internship in the Missouri Legislature in Jefferson City. That was an unsettling initiation, an introduction to something they never discussed in civics class. It was 1974, and I went to work in the office of State Representative Sue Shear, a Democrat from the St. Louis County suburb of Clayton. It was the first time I experienced moments of being very uncomfortable as a young woman surrounded by lots of men.

There were inappropriate things said to me and inappropriate behaviors that made me very uneasy. Representative Shear’s office was on the ground floor of the capitol, so I began my internship spending lots of time on the nearby elevator, as I was sent on errands to the upper floors of the building. One day I ended up in the elevator with two older male legislators and one of their assistants. They began asking if I liked “to party” and then tried to get me to come to one of their offices for some drinks. I felt trapped. For the rest of the internship, I took the stairs.

I also watched in horror at the way Sue’s colleagues marginalized her. They were patronizing and dismissive. When she was elected in 1972, she was the first woman to be recruited and supported by the Women’s Political Caucus in Missouri. There were only a handful of women in the Missouri Legislature then, and Sue was a crusader. She was willing to fight anyone anytime over the issue of women’s rights. But because she was sounding one note almost exclusively, she wasn’t taken as seriously as many of her women colleagues. With the determination of a bulldog, she wanted to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, though she didn’t make much headway. So although I loved and admired her, watching her made me realize that sheer determination and focus alone are not going to win the day. The Missouri Legislature never did pass the ERA.

There were women legislators who would try to be one of the boys, making deals and cracking dirty jokes. Judy O’Connor from northern St. Louis County won a special election in 1971, filling the seat that had been held by her husband, who was killed in a car accident on his way to the state house. Winnie Weber from House Springs in Jefferson County, known as “the life of the party,” had won her seat in 1970. Observing my female colleagues in the Missouri House in the eighties made me realize that self-effacing humor combined with a passionate focus on substantive issues could be effective, whereas either one in isolation, not so much.

A year after my internship with Shear, in 1975, I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in political science and immediately entered law school at the University of Missouri in Columbia. I got accepted elsewhere, but I went to Mizzou because I knew that being part of the network of lawyers in Missouri would help me more with any future political campaigns. I became close to many of my classmates, including David “Doc” Limbaugh, brother of the future conservative radio celebrity, and David Steelman, who would later marry Sarah Steelman, one of the three candidates who sought the GOP Senate nomination to oppose me in 2012. I had serious political differences with Doc and David, but it would not be the last time that I made fast friends with those who held opinions that were different from mine.

I didn’t like law school very much. I liked the trial-related courses, but property, trusts, wills, and tax law really didn’t engage me. Everyone was very competitive, so there was a lot of one-upmanship and talk of high-salaried jobs with big law firms. As a result I didn’t spend a lot of time hanging around the school; instead I took a job as a waitress in Columbia. When I studied, it was usually at my apartment or on my work breaks. My job gave me perspective, because when everyone else was stressing out over law school, I was trying to figure out whether the order I turned in for a medium rare steak had been correct.

After graduating from law school in December 1977, Kansas City was my destination. I chose it because I didn’t know anybody there and no one knew me. I wouldn’t be “Bill and Betty’s daughter.” I wanted to make it on my own. I had grown up for the most part in Co...

Revue de presse :

Street after street, door after door, I walked and knocked. “Hello, I’m Claire McCaskill, and I’m an assistant prosecutor. I’m running for state representative, and I’d appreciate your vote.”

I was twenty-eight years old, single, a renter with no money or political organization backing me up. It was 1982, and I was a young prosecutor with courtroom experience who was comfortable making a case and doing hard work. When I ran for my first political office, a seat representing part of Kansas City in the Missouri House, people told me I needed to knock on doors. I knocked on 11,432 of them.

While I remember many of these encounters, one has replayed itself in my head hundreds of times over the years. It was dusk on an early summer evening as I approached a small Tudor in a modest neighborhood. I’d been knocking for several hours by the time I reached this house. A man in his upper-middle years opened the door, and I rattled off my greeting. He looked me over slowly, up and down, and said, “You’re too young. Your hair is too long. You’re a girl. No way are you tough enough for politics. Those politicians in Jeff City’d eat you alive. Go find yourself a husband.”

And he slammed the door in my face.

I won that race—and I kept on running for the next thirty years.

From a very young age, I was driven. In school I spoke up so much I earned the nickname “Motor-mouth McCaskill.” I didn’t want to just get A’s; I wanted to win every spelling contest. I didn’t want to be just a cheerleader; I wanted to be captain of the squad. Until I got to college I didn’t realize that such drive wasn’t always socially correct. My parents had done an amazing job of protecting me from a very dangerous point of view: that women should not be ambitious.

My mom, Betty Anne McCaskill, emphasized early on that women can do anything men can do. She refused to let me and my sisters, Anne and Lisa, get a Barbie, Queen of the Prom board game when we were young. To win the game you had to get a dress and a boyfriend and go steady. “Dumb game. That is not how you win anything,” she told us. While she never discouraged marriage, she and Dad both reinforced the need for us to first be self-sufficient. In that sense, my parents were way ahead of their time in stressing independence. My dad’s words still ring in my ears: “You can’t find happiness with someone else until you are happy with yourself.” My dad, Bill, gave me the gift of incredible respect for a sense of humor. Even while I was ambitious, the people in my household taught me not to take myself too seriously. And as the most important male figure in my life, my father also gave me permission to be bossy and opinionated.

When I was in high school, I encountered my first situation where I had to choose whether to go along and be popular or to speak out even though I risked alienating some of my friends. The social sorority to which I belonged had always used popularity as the only measure for inclusion. I took the risk of saying that it might be a good idea to look at grades and school activities and maybe work for a little diversity if we were really focused on service as much as prestige. I felt strongly about this, and it hurt when my friends turned against me. That evening, as I was crying in my room, Dad quietly told me to snap out of it. He asked me to choose whether I wanted to be a leader or a follower, pointing out that followers never got their feelings hurt, but leaders always do. He told me one of his corny jokes and made me laugh. That was the year that Dad gave me John F. Kennedy’s book Profiles in Courage for Christmas.

Each year Dad encouraged me to enter the American Legion speech contest at West Junior High School. Though I made the finals in seventh and eighth grade, I never won. The contest required memorization of the speech, no notes allowed. One of those years I had the traumatic experience of forgetting my speech in front of the entire student body. Part of me wanted to sit out the competition in ninth grade, but a bigger part wanted to win. Dad and I talked about it and decided that my topic for this last try needed to be something I felt strongly about. I chose to give a speech about the Ku Klux Klan. He had me research the KKK, and we decided together that their offensive and repugnant oath would be a dramatic beginning to the speech.

I can recall exactly how I felt standing alone at the podium, and I remember where Dad was sitting. And I can still feel the surge of adrenaline when, as I opened with those sickening words of allegiance to racism, I felt the connection with the audience and the incredible high when the thunderous applause came at the end of the speech, when I closed with the Pledge of Allegiance. Later Mom told me that when they announced me the winner, Dad was crying. It was probably around that time that I started talking about being Missouri’s first woman governor.

If you wanted to predict where I might end up, there are some good clues in a series of episodes that took place during my junior and senior years at Hickman High School in Columbia, Missouri. I had been a cheerleader all through junior high and until my senior year at Hickman, when they brought in professional judges to pick the team and I didn’t make it. It was as if the roof had fallen in on my life. My younger sister, Lisa, can still recall coming home and finding me sprawled across the bed, sobbing, mascara running down my face. What a comedown. What a catastrophe.

To make up for losing my cheerleader’s spot, I launched a secret comeback by running for Hickman’s homecoming queen. It was a stealth operation because nobody really “campaigned” for the honor. The football team chose the queen, usually the girlfriend of one of the team captains. I figured out that all the votes from the linemen and the second- and third-string players were being taken for granted, and I methodically identified all these players and their girlfriends. Then I quietly began to reach out to them. I paid them special attention, did favors, arranged dates, and went out of my way to show I cared. I did it subtly and slowly for months.

At first the plan was all about me. But I came to learn that I really liked the people whose votes I was courting. They became my friends, and I started to believe that I was actually giving them some input into a process they never had before. The following winter I wore the homecoming crown, and although I wanted others to believe I won because I was popular, in fact I had carried out an effective political operation by identifying a constituency and working hard to gain its support. For years afterward I kept to myself what I had done, talking about it only with my closest friends. I’m still slightly embarrassed to admit that I campaigned for homecoming queen, but it’s important for women to own being strategic. To this day I remain friends with some of those linemen on the football squad.

Losing my cheerleading spot helped me in the long run. The only salvation I could find at that time was when I became Pep Club president and, at my dad’s urging, joined the competitive speech and debate squad. I had to learn how to speak on any topic I was given only moments before walking into the room for the tournament. It was a frightening thing to do, but I remember hitting my stride during the third contest and thinking, I can do this. That confidence has come in handy countless times in the courtroom, on the campaign trail, and on the floor of the U.S. Senate. I soon discovered that other students were warming up to me now that I had been brought down a notch or two from my cheerleading pedestal. I realized vulnerability can be an asset.

The day after I graduated from Hickman High School, I packed my beat-up Chevy Nova—bought with money I made working as a clerk at a fabric store—and took off for a job bussing tables at the Lodge of Four Seasons at the Lake of the Ozarks. Every summer throughout college I worked as a waitress at the Lodge, located about an hour from Columbia and the University of Missouri. You learn a lot about people when you wait on them. You learn how to communicate and how to calm people down when they’re upset or frustrated, and you learn that giving people information in a friendly manner can produce great results. That is another important skill in politics.

Before I graduated from high school, I made up my mind that I was going to law school. I pursued a political science degree at the University of Missouri and concentrated on getting good grades. I set goals for myself, and I’d often lie awake at night plotting out how to achieve them. I considered each step that would be necessary in the process and identified allies. Sometimes my ambition surprised me. As a freshman I pledged one of the school’s most prestigious sororities. I was the first woman to chair the university’s homecoming gala. I became a football hostess, a job in which you help recruit athletes. While landing the hostess position depended partly on looks, you also had to know enough about football to answer their questions and show you understood the game. You had to know the difference between a tight end and a linebacker because when you’re meeting with a potential recruit it is important to make him feel welcomed and needed, and knowing about his job as a football player was part of that.

Many years later, Anne Loew, one of my sorority sisters, talked about how, though it might have looked easy, I had put a lot of work into getting to where I wanted to be. “We’d walk into a party and all I’d want to do was grab a beer and have some fun,” she said. “But then I’d notice Claire working the crowd. She seemed to have an unerring ability to single out the most important people in any group—whether students or professors—and concentrate on them. It was a challenge to her to win them over. It didn’t matter if they were her enemies. Claire would be there, smiling and chatting. ‘Why have an enemy,’ she’d say to me, ‘when you can have a friend?’ ”

Over time Anne learned that I was working on a long-term plan—that each step forward was getting me closer to a specific goal. Jill McDonald, another friend from those days, didn’t like me at first because I seemed a little too opinionated, a little too pushy. But later she came to see those traits as independence. “Despite her ambition, in some ways Claire really didn’t care what other people thought of her,” Jill said. “In her personal life, she did what she wanted. In that area she never compromised to achieve anything, and yet somehow she still came out all right, though there were people who came to hate her for that attitude. Back then there were still lots of men and women around campus who wanted her to be just another meek sorority type. Claire just said ‘to hell with them.’ ”

More valuable to me than my political science classes were the outside experiences that came with them. For example, in 1974, when I was a junior, I conducted research for one of my professors, David Leuthold, by attending the Democratic Midterm Convention in Kansas City. Warren Beatty was there as a delegate, and it was interesting to me to see how much more attention the movie star received than the well-known feminist icon Bella Abzug. One summer I took a comparative government course at Georgetown University and interned in the office of Congressman Jim Symington of Missouri. My most valuable learning experience outside the classroom came with an internship in the Missouri Legislature in Jefferson City. That was an unsettling initiation, an introduction to something they never discussed in civics class. It was 1974, and I went to work in the office of State Representative Sue Shear, a Democrat from the St. Louis County suburb of Clayton. It was the first time I experienced moments of being very uncomfortable as a young woman surrounded by lots of men.

There were inappropriate things said to me and inappropriate behaviors that made me very uneasy. Representative Shear’s office was on the ground floor of the capitol, so I began my internship spending lots of time on the nearby elevator, as I was sent on errands to the upper floors of the building. One day I ended up in the elevator with two older male legislators and one of their assistants. They began asking if I liked “to party” and then tried to get me to come to one of their offices for some drinks. I felt trapped. For the rest of the internship, I took the stairs.

I also watched in horror at the way Sue’s colleagues marginalized her. They were patronizing and dismissive. When she was elected in 1972, she was the first woman to be recruited and supported by the Women’s Political Caucus in Missouri. There were only a handful of women in the Missouri Legislature then, and Sue was a crusader. She was willing to fight anyone anytime over the issue of women’s rights. But because she was sounding one note almost exclusively, she wasn’t taken as seriously as many of her women colleagues. With the determination of a bulldog, she wanted to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, though she didn’t make much headway. So although I loved and admired her, watching her made me realize that sheer determination and focus alone are not going to win the day. The Missouri Legislature never did pass the ERA.

There were women legislators who would try to be one of the boys, making deals and cracking dirty jokes. Judy O’Connor from northern St. Louis County won a special election in 1971, filling the seat that had been held by her husband, who was killed in a car accident on his way to the state house. Winnie Weber from House Springs in Jefferson County, known as “the life of the party,” had won her seat in 1970. Observing my female colleagues in the Missouri House in the eighties made me realize that self-effacing humor combined with a passionate focus on substantive issues could be effective, whereas either one in isolation, not so much.

A year after my internship with Shear, in 1975, I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in political science and immediately entered law school at the University of Missouri in Columbia. I got accepted elsewhere, but I went to Mizzou because I knew that being part of the network of lawyers in Missouri would help me more with any future political campaigns. I became close to many of my classmates, including David “Doc” Limbaugh, brother of the future conservative radio celebrity, and David Steelman, who would later marry Sarah Steelman, one of the three candidates who sought the GOP Senate nomination to oppose me in 2012. I had serious political differences with Doc and David, but it would not be the last time that I made fast friends with those who held opinions that were different from mine.

I didn’t like law school very much. I liked the trial-related courses, but property, trusts, wills, and tax law really didn’t engage me. Everyone was very competitive, so there was a lot of one-upmanship and talk of high-salaried jobs with big law firms. As a result I didn’t spend a lot of time hanging around the school; instead I took a job as a waitress in Columbia. When I studied, it was usually at my apartment or on my work breaks. My job gave me perspective, because when everyone else was stressing out over law school, I was trying to figure out whether the order I turned in for a medium rare steak had been correct.

After graduating from law school in December 1977, Kansas City was my destination. I chose it because I didn’t know anybody there and no one knew me. I wouldn’t be “Bill and Betty’s daughter.” I wanted to make it on my own. I had grown up for the most part in Co...

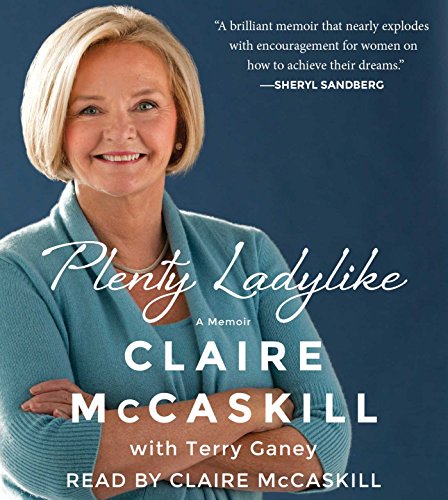

"Senator McCaskill is a role model for women who aspire to win on their own terms. Plenty Ladylike is a powerful, unapologetic primer on the successful exercise of real power and what it takes to get it, keep it, and use it. This is a brilliant memoir that nearly explodes with encouragement for women on how to achieve their dreams." (Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook COO and author of Lean In)

“Plenty Ladylike reclaims hard work, boldness, and tenacity as essential ladylike qualities. Claire’s successes, from demanding taxpayers’ dollars are used effectively to passing new protections for victims of sexual assault, make clear that women should run for and demand a seat at the table.” (Donna Brazile, Vice Chairwoman of the Democratic National Committee)

"Honest and fearless, Claire McCaskill is one of the most authentic and compelling people I have met in public life. In this candid memoir, she recalls a journey of struggle and triumph that underscores the unique challenges women face in a male-dominated arena. It's a great story." (David Axelrod, former Senior Advisor to the President)

"Claire McCaskill’s trademark invincibility was forged in childhood--inspired by exceptional parents, powered by a bone-deep self-confidence, and driven by a defiant rejection of any gender stereotyping that might stand in her way. In her electrifying and bracingly honest memoir, Plenty Ladylike, McCaskill reveals how her tireless ambition and steely spirit fueled the fascinating upward trajectory of her life. I was spellbound by McCaskill’s story, and I know that women everywhere will cheer along with me at her march into the pages of history." (Marlo Thomas, actress and author of Free to Be...You and Me)

"Claire is known by her colleagues for her courage, leadership, and resolve. Plenty Ladylike is an honest and heartfelt look into how she became the first woman from the state of Missouri elected to serve in the United States Senate. Her story is both instructional and inspirational for all people committed to the unfinished business of America: making our nation a place of liberty and justice for all, no matter your race, religion, or gender." (Cory Booker, US Senator)

"Claire McCaskill has always been a fighter for what she believes in, and a powerful advocate for women." (Ellen Malcolm, Founder of EMILY's List)

“A quietly charming, inspiring memoir.” (Kirkus Reviews)

“McCaskill’s memoir is straightforward, plainspoken, and at once deeply personal and thoroughly political.” (Publishers Weekly)

"A highly readable, relatively fast moving and surprisingly frank political autobiography." (Kansas City Star)

"Vivid detail. . . . What will strike a reader is not only her candidness when talking about the challenges of working with the men she has grown up with in politics but also her willingness to go where few politicians do and talk about deeply emotional parts of her life like her divorce, finding love again and the death of her mom, Betty Anne. . . . It’s plenty clear [Plenty Ladylike] is not just another politician’s book. . . . Amid stories of the tough road traveled by women in politics, Plenty Ladylike offers a narrative of encouragement for them to do it anyway." (The Joplin Globe)

"Regardless of the reader’s political bent, it would be hard not to appreciate McCaskill’s feisty ascent through what had been a male-dominated political realm. Her tale . . . rings true to her persona as an ambitious, plain-spoken leader who wins her way, without apology." (St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

"A crisp read. . . . It seldom slows down." (St. Joseph News-Press)

“An eye-opening read with perspective on the continual evolution of American politics.” (Biographile.com)

“Plenty Ladylike reclaims hard work, boldness, and tenacity as essential ladylike qualities. Claire’s successes, from demanding taxpayers’ dollars are used effectively to passing new protections for victims of sexual assault, make clear that women should run for and demand a seat at the table.” (Donna Brazile, Vice Chairwoman of the Democratic National Committee)

"Honest and fearless, Claire McCaskill is one of the most authentic and compelling people I have met in public life. In this candid memoir, she recalls a journey of struggle and triumph that underscores the unique challenges women face in a male-dominated arena. It's a great story." (David Axelrod, former Senior Advisor to the President)

"Claire McCaskill’s trademark invincibility was forged in childhood--inspired by exceptional parents, powered by a bone-deep self-confidence, and driven by a defiant rejection of any gender stereotyping that might stand in her way. In her electrifying and bracingly honest memoir, Plenty Ladylike, McCaskill reveals how her tireless ambition and steely spirit fueled the fascinating upward trajectory of her life. I was spellbound by McCaskill’s story, and I know that women everywhere will cheer along with me at her march into the pages of history." (Marlo Thomas, actress and author of Free to Be...You and Me)

"Claire is known by her colleagues for her courage, leadership, and resolve. Plenty Ladylike is an honest and heartfelt look into how she became the first woman from the state of Missouri elected to serve in the United States Senate. Her story is both instructional and inspirational for all people committed to the unfinished business of America: making our nation a place of liberty and justice for all, no matter your race, religion, or gender." (Cory Booker, US Senator)

"Claire McCaskill has always been a fighter for what she believes in, and a powerful advocate for women." (Ellen Malcolm, Founder of EMILY's List)

“A quietly charming, inspiring memoir.” (Kirkus Reviews)

“McCaskill’s memoir is straightforward, plainspoken, and at once deeply personal and thoroughly political.” (Publishers Weekly)

"A highly readable, relatively fast moving and surprisingly frank political autobiography." (Kansas City Star)

"Vivid detail. . . . What will strike a reader is not only her candidness when talking about the challenges of working with the men she has grown up with in politics but also her willingness to go where few politicians do and talk about deeply emotional parts of her life like her divorce, finding love again and the death of her mom, Betty Anne. . . . It’s plenty clear [Plenty Ladylike] is not just another politician’s book. . . . Amid stories of the tough road traveled by women in politics, Plenty Ladylike offers a narrative of encouragement for them to do it anyway." (The Joplin Globe)

"Regardless of the reader’s political bent, it would be hard not to appreciate McCaskill’s feisty ascent through what had been a male-dominated political realm. Her tale . . . rings true to her persona as an ambitious, plain-spoken leader who wins her way, without apology." (St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

"A crisp read. . . . It seldom slows down." (St. Joseph News-Press)

“An eye-opening read with perspective on the continual evolution of American politics.” (Biographile.com)

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurSimon & Schuster Audio

- Date d'édition2015

- ISBN 10 1442396806

- ISBN 13 9781442396807

- ReliureCD

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 17,50

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Plenty Ladylike: A Memoir

Edité par

Simon & Schuster Audio

(2015)

ISBN 10 : 1442396806

ISBN 13 : 9781442396807

Neuf

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Etat : New. . N° de réf. du vendeur 52GZZZ009Q9M_ns

Acheter neuf

EUR 17,50

Autre devise

Plenty Ladylike: A Memoir

Edité par

Simon & Schuster Audio

(2015)

ISBN 10 : 1442396806

ISBN 13 : 9781442396807

Neuf

Quantité disponible : 3

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Etat : New. . N° de réf. du vendeur 5AUZZZ000NKU_ns

Acheter neuf

EUR 17,50

Autre devise