Articles liés à Red Now and Laters: A Novel

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNWe were going to the rodeo. Despite all the rigmarole with loading up the horses, saddles, and ice chests in preparation for the trip, the entire experience was exhilarating. During the week he may have spent his days loading shipping containers at the Houston Ship Channel until he was exhausted or chanced his paycheck on the roll of the dice on Stassen Street or the dexterity of his pool cue at Jewel’s Lounge or listened to Mother’s harangues while trying to watch the Astros game, but none of that mattered on Sunday because on Sunday, Father was a bona fide rock star in the black rodeo circuit and nobody questioned that.

We loaded up a palomino named TJ. A beautiful, cream-colored horse that Father had been training for calf roping. Then we loaded in a jumpy quarter horse called Black Jack. That was my horse and part of Father’s blatant attempt to make me a horseman. Black Jack had come off the racetrack and was a bit skittish, prone to take off without any warning. And although I protested about Black Jack being my horse, wanting a kinder, gentler ride, Father was adamant. If he rares up on ya, grab them reins and jerk ’em and tell him to cut it out, he said. Take control of the animal is what he meant. Take control. Don’t get used or run over. Grab the reins. But it didn’t matter. I got thrown off that horse more than I care to mention. And every time I was thrown off, Father would run to me with worry and concern like that day in the flood when I was little. And he’d help me up and tell me not to cry.

“Crying never solved anything, Ti’ John. It only makes you focus on your failure and bad shit. Don’t cry. Focus on how to do things right the next time so that you don’t have to cry. Do you understand what I’m tryin’ to tell ya?” he said.

We rode in his brown Chevy pickup pulling a horse trailer down FM 521 South headed to Angleton, Texas. Cold Schlitz rested in the coffee holder next to my Big Red. Charley Pride crooned on the eight-track asking if anybody was going to San Anton’ or Phoenix, Arizona. The AC was on full blast. Driver’s-side window cracked slightly so that my middle name wouldn’t change to Benson & Hedges. A CB radio crackled under the ashtray with random gibberish, a foreign language understood by men who spent long hours on the white line. Father had been a member of that fraternity from time to time, privy to its secret codes and rituals.

“Daddy, you think they gonna let Cookie stay in Heaven?” I asked.

“Who’s Cookie?”

“The girl that got hit by the bus.”

“I imagine.”

“But she ain’t get baptized. Sister Marie Thérèse said you gotta be baptized to go to Heaven.”

He took his time with that one.

“Everybody don’t go to Heaven, Ti’ John,” he answered.

“They go to the hot place?” I asked.

He lit a cigarette.

“I’ma tell you something and you better not repeat it. Understand?”

I nodded.

“Ain’t no such thing as Hell, Ti’ John. That’s just some bullshit them white folks came up with to get people scared,” he answered.

“What about in the Bible?”

“White folks wrote the Bible.” He grabbed the CB receiver. “Breaker one-nine, pushing down 521 South, who got their ears on?”

He joined the precursor of online chat rooms—the CB chat room—effectively ending our discussion on the afterlife.

I stared at passing crops. Green. Brown. Tan. Brown. Green.

“Daddy, look at that,” I said, but he stared straight ahead while getting reports on Smokey in between lurid jokes. He didn’t see it, I thought.

About a hundred feet off FM 521 in a barren field of dirt I noticed a figure on its knees, hunched over. As we got closer I could see it was a man, a dark man in dark clothes wearing a large hat. He saw me staring. I think. I knew it. Just as we passed by, the man stood up, facing my curious eyes, took off his hat, and leaned forward with a deep ceremonious bow. It was friendly, respectful, even regal.

“Daddy, did you see that man?” I asked more urgently, but Father ignored me.

I peeked through the side view and the man was still there watching. I think he waved.

“That’s peas over there. See? Look at that. Boy, I usedta pick some peas back in Basile,” Father said fondly after hanging up the CB.

It didn’t matter which crop it was, he always would say he used to pick, cut, or dig that particular crop when he was growing up. Field peas. Mustard greens. Sugarcane. Potatoes. Rice. Turnips. Watermelons. And cotton. Cotton. Even Mother admitted to picking cotton back in the day. Now, when I first heard this cotton admission I recalled the TV movie Roots, with slaves picking cotton. It didn’t make sense to me. How could they have picked cotton? Response? Somebody or the other had a cotton farm and the cotton had to be picked. In Father’s case, it was part of his upbringing as sharecroppers if that’s what was growing. But Mother, she took a more noble explanation, saying that all of her cousins had to go to their grandparents’ house and toil under the sun to make the load as a rite of passage but, more important, as a lesson in hard work and how far black people had come.

Now, all of this was true. No exaggerations. And later I would discover that many people my parents’ age from Texas and Louisiana shared a similar plight. Some by necessity, like Father. Others as an excessive summer camp hosted by family members who still practiced the ancient art of cotton farming. Something about saying that you picked cotton carried a sense of history, strength, and perseverance. And these people from that generation downright bragged about that shit. I had to pick cotton. I had to pick cotton every summer. I had to pick cotton every summer or my uncle wouldna’ gave us nuthin’ to eat.

Since I associated picking cotton with slavery, I’d ask, “Did they whip you real hard?”

“What?” Father would ask.

“The white guy on the horse with the whip. Did he hit you real hard?” I’d inquire innocently, lamenting poor Kunta Kinte trying to escape a color twenty-inch Zenith plantation with foil paper on the antennas. Mother made me watch it, but Father wasn’t interested in reliving the past. I mean he really had a problem with Roots, which was really a show for white folks anyway. Why we gotta keep reminding ourselves about that shit? he’d say in his nonpolitical way. But keep in mind, Mother was the one who bragged about picking cotton, so a TV show that highlighted the labor was right up her child-rearing alley.

“If you was lazy out there, my uncle would get that belt,” both of them would say. Always an uncle who whips your ass extra special.

I continued with the questions about the crops, and Father was more than happy to identify them. In some ways, it was a reminder of Basile and the toils of being a sharecropper, but what I didn’t know was that he was an expert at things that grew from the ground.

He grinned and hummed Charley Pride in between sips of beer, puffs of tobacco, and my questions. But as we got closer to Angleton his mood began to shift and he quieted. It would soon be time for him to perform and he had to get in the zone.

We turned off FM 521 onto a gravel road that led into a desolate rough. Trucks and cars lined the sides of the road leading to an aluminum gate where an elderly black man in cowboy attire sold tickets for entry. Six dollars for adults. Three dollars for kids. Small, rectangular tickets were exchanged and we’d put those tickets in our hatbands. The rodeo arenas all looked the same, some larger or smaller than others. But always the same design, very functional and only the necessities.

A dirt road would lead to a large, usually one hundred yards, clearing in the middle of nowhere with a small arena built of rotting wood. Wooden bleachers sided the arena. Rotting wood, of course, with chutes and a wooden tower, where the announcer rambled from a scratchy PA system. Outside the arena, wooden, yes, rotting, outhouses were placed. And a shack with a huge barbeque pit in the rear served food and refreshments, and almost always hosted a jukebox and pool table.

This was the black rodeo circuit in Texas during the early 1980s. No sponsors. No telecast. Just hard-living rural black folks, mostly, who wagered their entrance fees on their ability to lasso or ride a large animal. Dangerous? Hell yes. Both the event and the people.

We waited in a line of trucks pulling horse trailers. Father scanned the large crowd. Some recognized his truck and would hoop and holler. Father casually nodded at his fans, hiding his glee. It took so long to become somebody. But he earned it—the good and the bad.

“John Frenchy!”

That’s what they called him after he returned to the South following the incident in Los Angeles, but he would say that he preferred the pseudonym rather than his given name because “them cowboy niggas is a rough bunch. They don’t need to know nothing about me.” But they did. They knew where he lived, where he kept his horses, where he worked, all the info. But then again, they admired him because he was deadly accurate with the lasso, the bullwhip, knives, pistols, arrows, spit, and every other thing he learned from those years in Basile, Louisiana, and from film sets in Agua Dulce Canyon, California. A regular Wild Bill Hickok with the charm and grace of a screen actor. He was smooth, a fact that didn’t go unnoticed by the women in attendance, married or unmarried.

But they also knew that he was tough and would fight at the drop of a dime. Nobody fucked with John Frenchy. Nobody.

Our horses snorted as they shuffled backward out of the trailer. TJ, carved from cream marble with a golden mane, made a stately exit. A proud animal indeed. Father grabbed the reins and huffed a command. The golden horse extended his front hooves, then dipped into a bow. Many looked at the spectacle as Father mounted the prostrating animal. Show-off. I put one foot in the stirrup of my skittish bastard, Black Jack, and he started moving, avoiding my mount, denying my glory.

“Yank the reins, Ti’ John.”

I did, but Black Jack kept moving so I had to mount in motion. Bastard.

Father lit a cigarette, then made a clicking sound. We headed out. He liked to take a spin around the arena when he’d first arrive to see his friends and let everybody know he was there. An impresario of the highest caliber. And off we’d go for our presentation lap. John Frenchy and Lil’ Frenchy. That’s what they called me, and I can’t say that I minded it much. It carried some weight with the rough kids of these rough people, because you sure as hell didn’t fuck with John Frenchy’s son.

Now imagine a black carnival where the smells of barbeque, cigarette smoke, and manure mixed into a delightful rustic aroma and nobody held their nose. All around us, black people of all ages in cowboy attire. Hats and boots. If your clothes were too clean then they’d assume you weren’t a real cowboy. As we moved slowly through the crowd on high atop our steeds, smiles and waves and whispers and nods confirmed Father’s status. He was a rock star and I was his son.

In the 1970s and early ’80s, Father competed in “breakaway” calf roping, where the roper flies out of the chute after a calf that’s given a bit of a lead. The roper must rope the calf, jump off the horse, slam the calf on its side, then quickly tie down all four legs with a smaller rope called a “pinky string.” The roper who can manage that in the shortest amount of time wins. That was Father’s money event. He was going to win that.

But he’d also compete in “team roping,” which involves two ropers who chase a steer out of a chute. One roper must lasso the steer’s horns (called “head”), and the other must lasso both back feet (called “tails”) for time. This required a different type of finesse because the head roper must swing the steer to make the back legs more available. This was John Frenchy’s big question as we rode around the arena. Who was going to be his partner for team roping?

Grown men would tease and pander to get Father to partner with them. They wanted the money and a chance for the buckle. Father enjoyed the attention and admiration with gibes and good humor, a subtle coaxing for side bets and lofty wagers. And while rodeoing is about athletic prowess and skill with the animal, it was also an occasion for good ole signifying, drinking, and gambling. This was outlaw business, and those who attended knew very well that only one or two constables might be present and, if so, probably drunk. So you had to watch your mouth and your stuff because anything could happen inside or outside the arena.

Father spotted his close friend, the bull rider Arthur Duncan, who would later become the first black man inducted into the Professional Bull Riding Hall of Fame.

“Eh, John Frenchy, who ya team-roping with?” Arthur Duncan said while helping me off the horse.

“Awh, none of these niggas can rope. Hell, I might have to carry me two ropes and work that steer by my damn self,” Father boasted as Arthur Duncan handed him a bottle of Wild Turkey for a hearty swig.

Father turned the bottle up, then chased it back with a Schlitz. A few slutty-looking rodeo bunnies eyed him from afar with suggestive gestures—batting fake eyelashes with over-applied eye shadow and nail-matching lipstick wet as water, exaggerated leans and bends to highlight skintight Gloria Vanderbilt jeans and danty snakeskin boots, and a “Hey, John Frenchy,” or a “You ropin’ today?” and almost always a “Where’s Mrs. Frenchy?” Answer? Mrs. Frenchy was at home asking the Blessed Mother to watch over her child and make certain Mr. Frenchy didn’t bring home anything she couldn’t wash out with Tide.

Of course, these rodeo bunnies found me absolutely adorable as it was Father’s habit to dress me in the same clothes that he wore when we’d go to rodeos. Strangely, only a few knew of John Frenchy’s affinity for dolls. I was a miniature version of him, I guess. And what greater trophy for a man than an actual living and breathing doll that looks just like you.

But these women fawned over Father incessantly, which only emboldened his hubris as we circulated around the arena before his events.

For his part, Arthur Duncan was the perfect colleague-in-recreation for Father. Duncan was a pure country boy from Brenham, Texas, who’d fine-tuned his championship bull-riding mastery in the Texas Prison Rodeo, where he served seven years for cracking his first wife’s skull after she commented on his complexion. Duncan was dark, very dark, and didn’t take too kindly to disparaging remarks about what the good Lord gave him. You didn’t talk about Arthur Duncan’s complexion or his pride and joy—his signature white cowboy boots.

When Duncan walked out of the Huntsville prison, in 1969, he became a black revolutionary but not with black berets, leather jackets, and propoganda. He carried his protest to the rodeo arenas. The white rodeo arenas. Besides his entrance fee, he typically had to pay much more to enter the events, which were basically white-only affairs in huge arenas constructed of steel and tin. Normally after he’d win an event he’d either have to fight envious cowboys or hightail it back to Brenham, usually both, in that order. But as the years passed and the number of championship buckles and subsequent fights grew, the white pro rodeo circuit accepted him—the man who fought for civil rights on the back of a bull with glowing lily-white cowboy boots.

Arthur Duncan and John Frenchy—the dangerous men—wra...

"A truly unforgettable world of spirits and magical men. Guillory's community is like the richest of cultural maps, peopled by some of the most memorable characters I have ever encountered." (Dolen Perkins-Valdez, author of Wench)

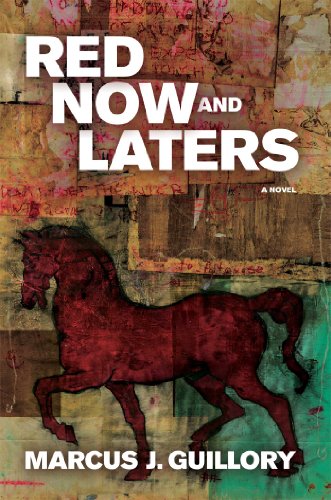

Guillory’s enchanting debut introduces Ti John, a young Creole growing up in Houston’s South Park neighborhood in the 1980s. Once a prominent, middle-class white community, South Park is now a ghetto plagued by violence and periodic flooding, a bizarre world saturated in mysticism, superstition, funk music, and disco. Ti John idolizes his embittered father, a cowboy and hero in the African American rodeo circuit, who grants his son a sense of freedom his overprotective Catholic mother denies him. All Ti John wants is to prove his manhood to the Ricky Street kids, whom his mother deems hoodlums. After witnessing a series of bloody misfortunes, most notably a bull disemboweling a friend’s father, Ti John disregards his mother’s cautions and emulates his father only to encounter romantic heartbreak, discover his father’s voodoo practices, and embark on a personal quest to unmask the mysterious ancestor whose ghost serves as his spiritual mentor. With dark humor and élan, Guillory’s complex and mesmerizing novel spans numerous eras of family history and southern folklore, offering a haunting yet soulful portrait of a neglected America culture. (Booklist)

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurAtria Books

- Date d'édition2014

- ISBN 10 1451699115

- ISBN 13 9781451699111

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages352

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 5,09

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Red Now and Laters Guillory, Marcus J.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. In shrink wrap. N° de réf. du vendeur 10-16525

Red Now and Laters

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover1451699115

Red Now and Laters

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think1451699115

Red Now and Laters

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_1451699115

Red Now and Laters

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard1451699115

Red Now and Laters

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Brand New!. N° de réf. du vendeur VIB1451699115