Articles liés à Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNThe contemporary reemergence of women’s rage as a mass impulse comes after decades of feminist deep freeze. The years following the great social movements of the twentieth century—the women’s movement, the civil rights movement, the gay rights movement—were shaped by deeply reactionary politics. When Phyllis Schlafly led an antifeminist crusade to stop the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment—the twenty-four-word constitutional amendment that would have guaranteed equal rights regardless of gender—finally succeeding in 1982, it was a sign that the second-wave feminist movement of the 1970s, and the righteous fury that had ignited it, had been sidelined.

More broadly, the Reagan era, in which increasingly hard-right reactionary politics had joined with a religious “moral majority,” gave rise to a cultural backlash to all sorts of social progress. Under sharp attack were the benefits, rights, and protections that afforded poor women any stability, as well as the parts of the women’s movement that had produced legal, professional, and educational gains for middle-class women, better enabling them to live independently, outside of marriage, the patriarchal institution that had historically contained them and on which they had long depended.

The right wing of the 1980s was driven to restrict abortion access and deregulate Wall Street while simultaneously destroying the social safety net, which Ronald Reagan had made sure was embodied by the specter of the black welfare queen. A 1986 Newsweek cover story, meanwhile, blared the news that a single woman at forty was more likely to get killed by a terrorist than get married. That later-debunked study was a key point of Susan Faludi’s chronicle of the era, Backlash, in which she tracked the varied, suffocating ways in which women’s anger was muffled throughout the Reagan years: how feminist activism was blamed for the purported “man shortage”; the day-care that enabled women to work outside the home vilified as dangerous for children.

Popular culture showed liberated white career women as oversexed monsters, as in Fatal Attraction, or as cold, shoulder-padded harpies who had to be saved via hetero-union or punished via romantic rejection (see Diane Keaton in Baby Boom, Sigourney Weaver in Working Girl). There was far too little space afforded to black heroines, and even some of the most nuanced were often crafted to serve male creators’ investments in how women’s liberation might serve their messages: Spike Lee’s view of the sexually voracious Nola Darling in the 1986 film She’s Gotta Have It and Bill Cosby’s Clair Huxtable, the successful matriarch who, given the context of Cosby’s own racial politics, served as a repudiation of black women who were not wealthy hetero-married mothers with law degrees.

Who wanted to be a feminist? No one. And the anxiety about the term wasn’t about any of the good reasons to be skeptical of feminism—like the movement’s racial exclusions and elisions—but because the term itself, the idea of public and politicized challenge to male dominance, had been successfully coded as unattractively old, as crazy, as ugly. Susan Sarandon, the rare celebrity who actually maintained her publicly left politics through the 1980s and 90s, once explained why even she of the unrelenting commitment to disruptive political speech preferred the misnomer “humanist” to calling herself a “feminist”: “it’s less alienating to people who think of feminism as being a load of strident bitches.”1

To be sure, there were eruptions of fury, coming from people—often from women—who were waging battles against inequities. In 1991, the law professor Anita Hill testified in front of an all-white, all-male Senate Judiciary Committee that Clarence Thomas, her former boss at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, then a nominee for the Supreme Court, had sexually harassed her. Many women were taken aback by the way the committee insulted, dismissed, and ultimately disbelieved Hill, confirming Thomas to the court, where he sits today.

“It was so stark, watching these men grill this woman in these big chairs and looking down at her,” Patty Murray, senator from Washington state, has recalled. Murray and a lot of other women were so outraged by the treatment of Hill that an unprecedented number of them ran for office in 1992. Four, including Murray, won Senate seats; one of them, Carol Moseley Braun, became the first-ever African-American woman elected to the Senate. Twenty-four women were elected to the House of Representatives for the first time, more than had been elected in any other previous decade.

These years sometimes included violent rage in response to racism: in 1992, after four white cops were acquitted by a mostly white jury in the brutal beating of African-American taxi driver Rodney King in Los Angeles, the city erupted in fury. Angry protesters looted stores and set fires; sixty-three people died. At the time, the news media and local politicians were quick to describe the events as riots, throwing around the term “thugs.”

But one Los Angeles Democratic representative saw something else in the riots: “There are those who would like for me . . . to tell people to go inside, to be peaceful, that they have to accept the verdict. I accept the responsibility of asking people not to endanger their lives. I am not asking people not to be angry,” said first-term congresswoman Maxine Waters, who represented a big part of the South Central Los Angeles neighborhood where much of the unrest was unfolding. “I am angry and I have a right to that anger and the people out there have a right to that anger.”2

Waters spent days tending to her constituents, bringing food, water, and diapers to Angelenos living without gas or electricity; she also pushed to charge the police officers civilly, and objected to Mayor Tom Bradley’s use of the word “riot” to describe events. Instead, she saw the politically rational frame for the resentments being expressed, calling it “an insurrection.”3

Eventually, Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Gates was fired, and two of the police officers were convicted for violating Rodney King’s civil rights.4

There were other moments of political protest: those against the World Trade Organization in Seattle in 1999 and marches against the invasion of Iraq in 2003, for example. But much of the spirit of mass, brash, sustained political fury that had animated the 1960s and 1970s was muffled in the 1980s and stayed that way for decades.

The journalist Mychal Denzel Smith has written of how this suppression worked itself out around expressions of black rage in the years in which he’d grown up, noting that during most of the 1990s, “there was no longer a Reagan or a Bush to serve as an identifiable enemy,” and that a pop commitment to “multiculturalism” permitted the illusion that racial progress had been achieved, so rage as a mass impulse had subsided.5

There had been a brief revival during the second Bush administration, Smith argued, recalling how, in the wake of the derelict response to Hurricane Katrina, rapper Kanye West had yelled that George W. Bush “doesn’t care about black people.” But that surge of fury had been quieted by the presidential campaign of Barack Obama. Obama’s historic drive had relied in part on his ability to reassure white voters that he was not an angry black man, that he was cut from a different cloth than some of his more bellicose black predecessors, including Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton, and did not in his demeanor threaten white supremacy. But Obama’s reputation for cordiality was gravely imperiled by the appearance of old-style black rage, when Reverend Jeremiah Wright, the man who had married the Obamas, became a campaign story, along with his much-played sermon, during which he’d exhorted, “God damn America!” The specter of Wright’s version of confrontational blackness was enough to remind America of Obama’s outsider status, and thus Obama was forced to quash it, becoming, in Smith’s words, “the first viable black presidential candidate to throw water on the flames of black rage.” The anger expressed by Wright, Obama would say in his famous speech on race, “is not always productive; indeed, all too often it distracts attention from solving real problems.”

But partway through the Obama administration, some political fury had begun to bubble over and break through this veneer of calm, in part driven by, or in ways that meaningfully sidelined, the angry voices of women.

ANGER RIGHT AND LEFT

Perhaps the most politically effective strike came from the right, with the Tea Party protests that began in 2009, soon after President Barack Obama took office. In response to Obama’s plan to bail out some homeowners who’d been caught in the housing crisis, cable news reporter Rick Santelli angrily called on television for the “Tea Party” to object. The reference, of course, was to the 1773 revolutionary protest of colonists who threw tea in Boston Harbor to register their objection to being taxed by Britain, which was using tariffs not to support the colonies but to stabilize its own floundering economy, and had imposed them on colonists who had no representation in British Parliament.6

The contemporary version was portrayed as a leaderless grassroots movement, though almost from its start, right-wing mega donors the Koch brothers had been funding its protests and its candidates. In theory, the agitation was in response to the far right’s view that Barack Obama’s administration was misusing taxpayer money, but the Tea Party was also driven by a wave of revanchist rage and racial resentment toward Barack Obama; no amount of nonconfrontational rhetoric could convince overwhelmingly white Tea Partiers he wasn’t a threat to their status and supremacy.

Though the public face of the Tea Party protesters was that of furious white men—often dressed in colonial-era tricorn hats in their early gatherings—some polls indicated that the majority of the faction’s supporters were women. Its most audible early female voice belonged to former vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, who in one address to activists called the movement “another revolution.” In 2010, a number of Tea Party–affiliated female candidates ran; Palin, who’d cast herself as a pit-bullish hockey mom, dubbed them “Mama Grizzlies.” And while the movement’s theatrics—funny hats and grizzly bears—were reminiscent of some of the performative exertions of the Second Wave, its mission was the precise opposite, more of a callback to the Schlafly-led antifeminist crusades of the 1970s and 80s.

Somehow, as with Schlafly, these women voicing their anger and throwing around their political weight weren’t caricatured as ugly hysterics; instead they were permitted to cast themselves as patriotic moms on steroids, some bizarro-world embodiment of female empowerment, despite the fact (or, more precisely, because of the fact) that what they were advocating was a return to traditionalist roles for women and reduced government investment in nonwhite people. Once they landed in the United States Congress, their obsessive mission was to vote to take away the federal funding received by family planning programs, to outlaw abortion, to punish Planned Parenthood, and to reduce government safety net programs such as food stamps and what remained of welfare.

“Conservative women have found their voices and are using them, actively and loudly,” Tea Partier Rebecca Wales told Politico in 2010. Another Tea Partier, Darla Dawald, put it this way: “You know the old saying ‘If Mama ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy’? When legislation messes with Mama’s kids and it affects her family, then Mama comes out fighting—and I don’t mean in a violent way, of course.”7

As more moderate Republicans got knocked out of their seats by Tea Party candidates, and those who remained moved further right, an angry protest in New York was drawing crowds of agitators from the other side. In the fall of 2011, in Zuccotti Park in downtown Manhattan, young people gathered to voice their fury at economic inequality, the widening gap between rich and poor, the rampant deregulation of and tax breaks for corporate America and Wall Street, and the steady gutting of social welfare programs.

Occupy Wall Street’s impact on the American left was crucial and long-lasting; the movement helped to popularize the view of economic inequality that set the 99 percent against the nation’s richest 1 percent. It was both a symptom and a fomenter of increased interest in socialist economic policy. That interest would help push the Democratic Party—which had for decades run screaming from the notion of even “liberalism”—further left, boosting the profiles and fortunes of politicians including Elizabeth Warren, who was elected Senator for Massachusetts in 2012, and Bernie Sanders, an independent who’d served in Congress for twenty-six years and would mount an electrifying campaign for the presidency in 2016.

Many different types of people participated in Occupy—estimates varied, but reportedly around 40 percent of the protesters were women, and 37 percent identified as nonwhite, making it far closer to representative of the United States than, say, Congress.8–10 Yet despite the fact that its structure was consciously collaborative and nonhierarchical, it was nevertheless a movement dominated publicly by the voices and ideas of white men. There were enough allegations of rape, groping, and sexual assault at Zuccotti Park that after several weeks, women-only tents were set up. Kanene Holder, an artist, activist, and black woman who served as one of Occupy’s spokespeople, told the Guardian that even within this progressive space, “white males are used to speaking and running things. . . . You can’t expect them to abdicate the power they have just because they are in this movement.” Eventually, Occupy had to adopt special sessions in which women were encouraged to speak uninterrupted.11

More than that, some of the righteously radical men who dominated Occupy were reportedly inhospitable to internal feminist critique. As one activist, Ren Jender, wrote after a proposal to better address sexual assault allegations was met with defensive anger from some of these radically progressive men, “I wasn’t angry with only the people who . . . said stupid, misogynistic shit . . . I was angry with the greater number of people who hadn’t confronted the misogyny.”12 Occupy was a reminder to many who agreed with its principles that the left was no more free of gender hierarchies and power abuses than the rest of the country.

Then, in 2013, in the wake of the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the murder of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin, the longtime progressive activist Alicia Garza wrote a note on Facebook, which concluded with the sentences, “Black people, I love you. I love us. We matter. Our lives matter.” The artist and activist Patrisse Khan-Cullors appended a hashtag to it, #BlackLivesMatter; the writer and community organizer Opal Tometi helped to push the message out over social media.

A movement—born of grief, horror, and unleashed fury at the persistent killing of African Americans by the state, by the police—was born. And while it, like Occupy and the Tea Party, was purposefully nonhierarchical in its internal structure, it had been founded by women, and many of the most prominent voices of the movement belonged to women, including Brittany Packnett, Johnetta Elzie, Nekima Levy-Pounds, and Elle Hearns. Khan-Cullors later wrot...

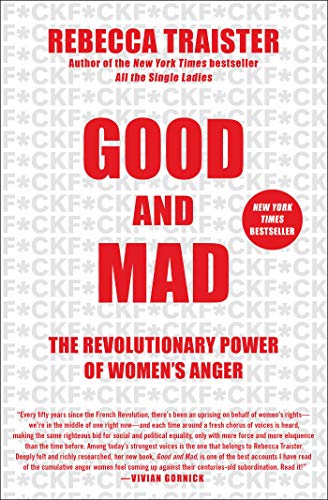

“[A] rousing look at the political uses of this supposedly unfeminine emotion...written with energy and conviction...galvanizing reading.”—NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

“Urgent, enlightened... well timed for this moment even as they transcend it, the kind of accounts often reviewed and discussed by women but that should certainly be read by men...realistic and compelling...Traister eloquently highlights the challenge of blaming not just forces and systems, but individuals.”—WASHINGTON POST

"While the anger of men is seen as 'stirring' and 'downright American,' women's is 'the screech of nails on our national chalkboard,' asserts journalist Traister in this invigorating look at the achievements of angry women from Carrie Nation to Beyoncé to the Parkland high school students. Through this lens she revisits the 2016 election, #blacklivesmatter and the #metoo movement (including her own Harvey Weinstein story) and cites a study showing you can tolerate pain longer - damn! - if you curse. Perfectly timed and inspiring.”—PEOPLE (BOOK OF THE WEEK)

“Traister specializes in writing about feminism and politics, and she knows the turf...especially astute in emphasizing the ways in which black women laid the cornerstones for women’s activism in this country...Feminism forces certain complexities into the stream of our daily lives, and Traister has a great gift for articulating them.”—TIME MAGAZINE

"Cathartic...a celebration of a catalytic force that burns ever brighter today."—O MAGAZINE

“From suffragettes to #MeToo, Traister’s book is a hopeful, maddening compendium of righteous feminine anger, and the good it can do when wielded efficiently—and collectively.”—VANITY FAIR

"An admirably rousing narrative."—ATLANTIC

"A resounding polemic against political, cultural, and personal injustices in America...With articulate vitriol backed by in-depth research, Traister validates American women's anger.... Traister has meticulously culled smart, timely, surprising quotations from women as well as men. The combined strength of these many individual voices and stories gives the book tremendous gravity.... A gripping call to action that portends greater liberty and justness for all.”—KIRKUS REVIEWS (STARRED REVIEW)

“A trenchant analysis... Traister argues forcefully that women are an ‘oppressed majority in the United States,’ kept subjugated partly by racial divisions among the group. Traister closes with a reminder to women not to lose sight of their anger—even when things improve slightly and ‘the urgency will fade... if you yourself are not experiencing’ injustice or look away from it.”—PUBLISHERS WEEKLY (STARRED REVIEW)

"Timely and absorbing, Traister's fiery tome is bound to attract attention and discussion. Traister takes a deep dive into the current political climate to explore the contemporary and historical relationship women have with anger and the ramifications of expressing and suppressing feminine rage. Traister uses...startlingly obvious double standard[s] to explore how attaching negative connotations to women's anger has always been used to silence and dismiss them."—BOOKLIST (STARRED REVIEW)

“Good and Mad is Rebecca Traister's ode to women's rage—an extensively researched history and analysis of its political power. It is a thoughtful, granular examination: Traister considers how perception (and tolerance) of women's anger shifts based on which women hold it (*cough* white women *cough*) and who they direct it toward; she points to the ways in which women are shamed for or gaslit out of their righteous emotion. And she proves, vigorously, why it's so important for women to own and harness their rage—how any successful revolution depends on it.”—BUZZFEED

"Women are angry, and Rebecca Traister is just the person to chart the topography of their rage, its causes, and its effects....A galvanizing, timely study of righteous rage.”—ELLE

"With Traister’s incisive prose and a topic that couldn’t be more timely, this book is sure to be a fiery read.”—HUFFINGTON POST

"A deeply research treatise on female anger - its sources, its challenges, and its propulsive political power.”—ESQUIRE

"Brilliant and bracing."—THE NATION

"[Traister] writes with convincing clarity...a feel-good book."—JEZEBEL

"A bracing, elucidating look at how transformative it can be for women to harness our rage, and how important it is to use that anger, that energy, for revolution." —NYLON

"Brilliant and impassioned and, yes, angry." —MINNEAPOLIS STAR TRIBUNE

"Good and Mad comes out at just the right time...the [Kavanaugh] hearing and its aftermath just proved the point Traister was making all along."—MOTHER JONES

"Traister's reported manifesto on feminism after Trump...offers a forceful...inventory of the ways in which women’s anger in the public sphere is exaggerated, pathologized, and used to discredit them in a manner unimaginable for men."—BOOKFORUM

"An exploration of the transformative power of female anger and its ability to transcend into a political movement...Read this."—PUREWOW

"One of our country’s wisest writers on gender and politics."—PORTLAND MONTHLY

“Every fifty years since the French Revolution there’s been an uprising on behalf of women’s rights—we’re in the middle of one right now—and each time around a fresh chorus of voices is heard, making the same righteous bid for social and political equality, only with more force and more eloquence than the time before. Among today’s strongest voices is the one that belongs to Rebecca Traister. Deeply felt and richly researched, her new book, Good and Mad, is one of the best accounts I have read of the cumulative anger women feel, coming up against their centuries-old subordination. Read it!”—VIVIAN GORNICK

“Rebecca Traister has me convinced in this deftly and powerfully argued book that there will be no 21st century revolution, until women once again own the power of their rage. Righteous fury leaps off every page of this book, with example after example, from the present and the past, coaxing, chiding, and indeed reminding us, that the political uses of women's anger have been good for America. As I read, my blood started pumping, my fist tightened and my spirit said, "hell yeah! We aren't going down without a fight." Women's anger rightly placed and soundly focused can be good for America, once again. In fact, it is essential. Tell the truth: We're all sick and tired of being sick and tired. It's high time we got good and mad.”—DR. BRITTNEY COOPER, author of Eloquent Rage

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurS&S/ Marysue Rucci Books

- Date d'édition2018

- ISBN 10 1501181793

- ISBN 13 9781501181795

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages320

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 1501181793-11-17409785

Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur DADAX1501181793

Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Womens Anger

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 521X7W000867

Good and Mad

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 26376279858

Good and Mad

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 370814189

Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_1501181793

Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Womens Anger

Description du livre Etat : New. . N° de réf. du vendeur 52GZZZ009WIJ_ns

Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger

Description du livre Etat : New. Book is in NEW condition. N° de réf. du vendeur 1501181793-2-1

Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger

Description du livre Etat : New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-1501181793-new

Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Brand New Copy. N° de réf. du vendeur BBB_new1501181793