Articles liés à Phenomenal: A Hesitant Adventurer s Search for Wonder...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

PROLOGUE

A REPORT CAME OVER THE RADIO IN SWAHILI: SOMEONE HAD SPOTTED A cheetah and her cubs.

“We’d have to drive fast to get there. Do you want to go?” my guide David Barisa asked, breathlessly. David was in his thirties, but he had a certain youthful panache given his shaven head, gold-plated sunglasses, and street-savvy nubuck boots. I couldn’t tell if his excitement was over the predator sighting or the excuse to speed.

“Sure,” I said.

We’d been watching the largest wildebeest herd I’d seen in the Serengeti, roughly 10,000 animals grazing and shuffling their feet in migration. Each year, some 1.3 million wildebeest move full circle through Kenya and Tanzania, following rains. They’re joined by zebra and gazelle, as well as a cast of hungry characters that lurk in the fray. And the drama of all this—as it’s taught in textbooks—was transpiring before me.

In the distance, thousands of additional wildebeest were clumped on the horizon, moving like silt-colored rivers. Breezes brought the sweet, nostalgic smell of hay. We bounded across rutted roads while David reeled off names of the animal groupings we’d seen over the past few days: clan of hyena, pack of wild dogs, pride of lions, herd of elephants.

“So, what do you call a group of cheetah?” I asked.

“They’re usually alone,” David said, grinding a gear. “But when I see them together, I just call them a family.”

I had to ask because I’m not a scientist. No, I’m a part-time teacher and freelance writer, mother of a young child, wife of a carpenter. So what was I—grader of papers, changer of diapers—doing gallivanting around the Serengeti? Why had I left my husband and two-year-old son back home in the hills of southern Appalachia?

My answer might come across as insane, or—at the very least—overly dramatic.

But here’s the truth: I was on an epic quest for wonder.

I’d been chasing phenomena around the world for more than a year when I arrived in the Serengeti, and I still had many miles to go. But my inspiration had been sparked even before I became a mother, when—three years before my son’s birth—I visited the overwintering site of the monarch butterfly in central Mexico. Before I accepted the magazine assignment that took me there, I’d never even heard of the monarch migration, during which nearly the entire North American population comes to roost in a small swath of forest. But witnessing millions of butterflies swirling, dipping, and gliding over a single mountaintop gave me an actual glimpse of what I mean when I refer to myself as spiritual but not religious.

And—in difficult times—memories of that experience sustained me.

I don’t know that I suffered clinical postpartum depression when my son was born, but I began to empathize with the horror stories the condition can lead to. Inspired by butterflies, I had long ago dreamed up a list of other natural phenomena I’d like to experience. But travel to far-flung lands? Once I had a baby, I considered myself lucky to make it to the grocery store before it was time for bed.

Still, I mused: Children have the capacity to marvel over simple things in nature—leaves, twigs, pebbles. Couldn’t exploring just a few of earth’s most dazzling natural phenomena—steeped as they are in science and mythology—make the world similarly new again, reawakening that sort of wonder within me? Drudgery, after all, has nothing to do with growing up if we do it right and—beyond tending to the acute physical needs of a child—little to do with what it means to be a good parent.

Right?

Back then, I didn’t know that acting out my self-designed pilgrimage would put me in the path of modern-day shamans, reindeer herders, and astrophysicists. I had no idea there were lay people from all over the world, from all walks of life, already going to great lengths to undertake the sorts of phenomena chases I’d dreamed up. Some took odd jobs to stay under the northern lights. Others left white-collar positions to make time for swimming in glowing, bioluminescent bays. These were people who braved pirates to witness everlasting lightning storms, stood on volcanoes, stared into solar eclipses. They trusted their instincts, followed their passions, willfully shaped their days into the lives they most wanted to lead.

And, somewhere along the way, I became one of them.

David pulled into a line of safari vehicles. The cheetah family consisted of a momma and three cubs. We stood in the pop-up roof of our Land Cruiser to see into the heart of their grassy nest. After a few minutes, the mother decided to rise. Her babies followed, in single file, and she crossed the dirt road to approach a wildebeest herd.

When they were still a ways out, the cubs took a seated position. “She’s telling them to stay back,” David said. The mother moved on. When she was just beyond the herd, she stopped to watch. “She’s teaching them how to stalk,” David reported. “How to survive. She’s watching for a young wildebeest, the weakest of the herd.”

The cubs were dark fuzz balls floating in a sea of grass. The mother cheetah stood taller. All her babies’ eyes were on her, watching. The light of day was beginning to fade. A giant elder wildebeest walked five feet in front of her. I gasped. Still, she waited.

“He is too big for her,” David said.

Finally, she found a baby wildebeest that had been pushed to the edge of the herd, and she slipped through grass like a fish slicing through a wave. The young wildebeest reacted, going from standing to swerving in seconds flat and, before I could even take a breath, a mother wildebeest appeared. She pushed the baby to the center of the herd, which erupted into honking that rippled across the savanna.

“They’re warning each other,” David said, like a foreign language interpreter. The cheetah was still, as if she’d forgotten something. “She doesn’t like to waste energy chasing something she doesn’t think she can catch.”

I quietly cheered for the young wildebeest. He was, after all, the main hero of the migratory story. Wasn’t he? I watched the cheetah turn back toward her babies, who had traced her every move. Her head hung low. She appeared to be sulking. “She’s going back to tell them they’re going to bed hungry tonight,” David said.

There were no clear winners. No easy answers. Only hard questions and survivors. But, because I had, for so long, only seen the pain of the wild on television, I had forgotten that there is also this: Long days of grazing through fields, listening to wind. Whole weeks spent sleeping in trees.

David, who had spent nearly every day of that year cruising the Serengeti, had seen only four predator kills in his lifetime. But he’d logged thousands of hours of watching animals—prey and predators alike—relaxing. This is the sort of life human bodies were also built for—acute stress and long periods of leisure, not the other way around.

A small group of wildebeest stopped to watch us pass. They were headed to the larger herd. Their life was a process, a cycle, a never-ending circle. But wasn’t mine, too? All my life, I’d thought: If I can just get into that college. If I can just make more money. If I can just birth this baby. If I can just get him through those scary first few months. If I can just make it through my first three weeks back at work. If I can just get my son potty trained. If I can just get a book contract. If I can just make it through the next eight nights sleeping alone in a canvas tent. If I can just. If I can just. If I can just.

Staring into the field of hooves pounding the earth, it was clear I had been denying myself this: The seasonal migrations of my life, the initiations, would never end. There would always be a proving ground to face. But acknowledging and embracing this was crucial to moving forward. It seemed a path to reduced anxiety, and I could surely use that. Letting go of the abstract idea that at some point my life would be more complete than it was that very moment felt like letting go of some sort of underlying, constant fear I wasn’t aware I had. Standing in the center of the Serengeti, it was apparent: I would benefit from balancing my abstract human thoughts with the visceral, phenomena-centered viewpoint of the animals that lived there.

Phenomenal is defined as that which is amazing. It also means that which is directly observable to the senses. And what began as a tour of extraordinary sights had evolved into the story of how—in an abstract, digital world of overspecialization—I was becoming the expert witness of my own life. When I returned home—as I did for months at a time, in between one- and two-week phenomena chases—I brought an expanded, global sense of wonder to bear on my own backyard, alongside my family.

“They are going to cross,” David said, nodding toward wildebeest that had lined the dirt road. Their pulse would quicken as they ventured out, but once they were back in the grass, it would slow. They’d move on, in every sense of the phrase. David picked up speed, determined to reach camp before dark. I turned to watch the animals brave their crossing, but all I could see was a cloud of volcanic dust rising in our wake.

CHAPTER 1

METAMORPHOSIS

I AM FRANTICALLY SEARCHING FOR MY NEWBORN SON, ARCHER. I’M ON my knees. My hands are slipping across cold hardwood floors. I grope my mattress’s metal frame, the legs of his crib. I’ve already thrown all the covers off my own bed, convinced he was suffocating in down.

When my panic reaches an apex, I wake up.

Sleepwalking. Night terrors. I have no idea what to call these episodes, but they have become a regular part of my life. More than once, at sunset, I have wept knowing I was assured another sleepless night to come. Sometimes, I cry into the night, watching my son nurse in his sleep as my husband, Matt—a bookish woodworker with a collection of self-designed tattoos—snores nearby.

Matt does not parent at night. That was established early on. Though I’m already back at my day job—teaching writing classes between nursing sessions—he is working with power tools. Sleeplessness and power tools are not a good mix, and anyway, Archer wants milk. I am the supply. He is the demand. We are sharing my body. I am his ecosystem. He is mine. And it feels like we’re clinging to each other for dear life. Matt is in our orbit, but he has become a distant planet.

When I am fully awake, I see Archer safely sleeping in his crib. I glance at the notebook where I record each of his nursing sessions so that I’ll remember to rotate sides, lest my raw breasts began to bleed, again. He is nursing nine times every twenty-four hours, a system that means he is attached to my person, suckling, almost constantly.

I hear his every movement, each breath. I read too much about Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. I cannot relax. I have not slept more than three straight hours since he was born, but I am especially shaken by the night’s episode, which has actually brought me to my knees.

My mouth is dry. My hands press against hickory floors.

I rise to get a glass of water that my body will, in time, turn to milk like holy wine.

Dawn won’t offer assurances. Days feel like hour-upon-hour of living underwater: the outside world muffled, every movement slowed to a languid speed. My friends tell me I seem to be handling things well. Things being the fact that my colicky son does none of the quiet, cooing lap sitting that seems so common in other people’s babies.

I wonder if it’s because I am afraid to tell the whole truth—what happens beyond the hours I spend staring at my son in wonderment, amazed at the miracle of his life. I love and marvel over him as if he were my own heart pushed into the world and, still beating, set on top of my chest. Yet I cannot help but mourn the loss of something I can’t quite place. I have an inner emptiness—literal and figurative—that I’ve never felt before. It’s as though nourishing his life has built a new chamber in my body that is now cavernous and empty, waiting to be filled.

I make my way into the living room without turning on any lights and walk toward a window, half expecting to catch sight of a bobcat. I see only the river below, a distant forest, and the hill leading to our garden plot. I feel like I am the only being awake in the world and—despite the fact that I have just doubled the number of people I share a house with—I have never felt more alone.

· · ·

To his credit, Matt perpetually tries to bring friends back into our lives with more regularity, but his attempts—often grand, as in “Oh, did I mention I invited ten people over for dinner tomorrow”—don’t always go over well. In fact, they often lead to arguments and, to my chagrin, me throwing fits and—in my worst moments—food. Are these out-of-control reactions the result of hormones, exhaustion, or are they proof I am becoming someone unrecognizable?

I hold Archer, literally, all day long. He will not lie in a crib without crying and I—struggling with feelings of confusion, spousal resentment, and guilt over things I can’t quite pinpoint—cannot leave my baby when his face is wrenched. So, he sleeps on me. He plays on me. Constantly. Sometimes, especially around dinner, even this does not quell his crying episodes. I sing. I dance. I cry.

I have no hope of ever sleeping again. I have no hope.

I develop tendonitis in my arm. It hurts when I twist it to put him down, punishment I accept for thinking I might be able to go to the bathroom without a companion. I forget to brush my teeth. I don’t shower. I can’t figure out how to balance these simple things against my need to feel I’m doing a good job—the right things, what I’m supposed to do.

When a friend tells me that her baby takes three-hour afternoon naps, about how she’s concerned her child might be sleeping too much, I have a lurching physical reaction. I do Internet searches that lead me to terms like “wakeful baby” to explain why my experience is so very opposite. I find articles about wakeful babies being of higher intelligence, having a keen sense of curiosity. I want to believe them, but I suspect these articles were penned by parents like me as a form of solace in an excruciating time.

Finally, one day at around the six-month mark, I admit to myself that I am going to have a nervous breakdown if I don’t take a shower each morning. I turn on a white-noise machine and put Archer in his crib. His tiny features crinkle like tissue paper being balled. His complexion turns crimson. I turn the water on and try to relax, impossible in my near-psychotic state. I hurriedly rinse my hair—which has begun to fall out in clumps as my body attempts to readjust hormonally—and I run back to him.

My friends, mothers, tell me that I will slowly get my life back. I don’t believe them. My biggest fear—my secret fear—is the same one that plagued me years ago when I took a soul-killing receptionist job to quell my parents’ concerns about health care coverage: This is what my life is going to be from now on. Only, I no longer have the solace of a reception area full of New Yorker archives. It is impossible to read while nursing, because the rustling of pages wakes...

“What a cool and fascinating ride. Leigh Ann Henion has tackled one of the great questions of contemporary, intelligent, adventurous women: Is it possible to be a wife and mother and still explore the world? Her answer seems to be that this is not only possible, but essential. This story shows how. I think it will open doors for many.”

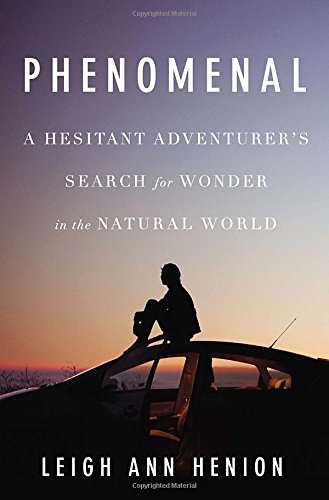

Heartfelt and awe-inspiring, Leigh Ann Henion’s Phenomenal is a moving tale of physical grandeur and emotional transformation, a journey around the world that ultimately explores the depths of the human heart. A journalist and young mother, Henion combines her own varied experiences as a parent with a panoramic tour of the world’s most extraordinary natural wonders.

Phenomenal begins in hardship: with Henion deeply shaken by the birth of her beloved son, shocked at the adversity a young mother faces with a newborn. The lack of sleep, the shrinking social circle, the health difficulties all collide and force Henion to ask hard questions about our accepted wisdom on parenting and the lives of women. Convinced that the greatest key to happiness—both her own and that of her family—lies in periodically venturing into the wider world beyond home, Henion sets out on a global trek to rekindle her sense of wonder.

Henion’s quest takes her far afield, but it swiftly teaches her that freedom is its own form of parenting—one that ultimately allows her to meet her son on his own terms with a visceral understanding of the awe he experiences every day at the fresh new world. Whether standing on the still-burning volcanoes of Hawai‘i or in the fearsome lightning storms of Venezuela, amid the vast animal movements of Tanzania or the elegant butterfly migrations of Mexico, Henion relates a world of sublimity and revelation.

Henion’s spiritual wanderlust puts her in the path of modern-day shamans, reindeer herders, and astrophysicists. She meets laypeople from all over the world, from all walks of life, going to great lengths to chase migrations, auroras, eclipses, and other phenomena. These seekers trust their instincts, follow their passions, shape their days into the lives they most want to lead. And, somewhere along the way, Leigh Ann Henion becomes one of them.

A breathtaking memoir, Phenomenal reveals unforgettable truths about motherhood, spirituality, and the beauty of nature.

Oprah.com

"Part travel memoir, part parenting manifesto and part inquiry into those 'fleeting, extraordinary glimpses of something that left us groping for rational explanations in the quicksand of all-encompassing wonder.'"

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurPenguin Press

- Date d'édition2015

- ISBN 10 1594204713

- ISBN 13 9781594204715

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages288

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Phenomenal: A Hesitant Adventurer s Search for Wonder in the Natural World

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Brand New!. N° de réf. du vendeur VIB1594204713

Phenomenal: A Hesitant Adventurer?s Search for Wonder in the Natural World

Description du livre Etat : new. Book is in NEW condition. Satisfaction Guaranteed! Fast Customer Service!!. N° de réf. du vendeur PSN1594204713

Phenomenal: A Hesitant Adventurer s Search for Wonder in the Natural World

Description du livre Etat : New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition 1.05. N° de réf. du vendeur bk1594204713xvz189zvxnew