Articles liés à Goya

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNI had been thinking about Goya and looking at his works for a long time, off and on, before the triggering event that cleared me to write this book. I knew some of his etchings when I was a high-school student in Australia, and one of them became the first work of art I ever bought-in those far-off days before I realized that critics who collect art venture onto ethically dubious ground. My purchase was a poor second state of Capricho 43, El sueño de la razón produce monstruos ("The sleep of reason brings forth monsters"), that ineffably moving image of the intellectual beset with doubts and night terrors, slumped on his desk with owls gyring around his poor perplexed head like the flying foxes that I knew so well from my childhood. The dealer wanted ten pounds and I got it for eight, making up the last quid with coins, including four sixpenny bits. It was the first etching I had ever owned, but by no means the first I had seen. My family had a few etchings. They were kept in the pantry, face to the wall, icons of mild indecency-risqué in their time-in exile. My grandfather, I suppose, had bought them, but they had offended my father's prudishness. They were the work of an artist vastly famous in Australia and wholly unknown outside it, a furiously energetic, charismatic, and mediocre old polymath called Norman Lindsay, who believed he was Picasso's main rival and whose bizarre mockoco nudes-somewhere between Aubrey Beardsley and Antoine Watteau, without the pictorial merits of either and swollen with cellulite transplanted from Rubens-were part of every Australian lawyer's or pubkeeper's private imaginative life.

That was what my adolescent self fancied etchings were about: titillation. Popular culture and dim sexual jokes ("Come up and see my etchings") said so. Whatever was on Goya's mind, though, it wasn't that. And as I got to know him a little better, through reproductions in books-nobody was exhibiting real Goyas in Australia all those decades ago; glimpsing El sueño de la razón was a fluke-I realized to my astonishment what extremity of the tragic sense the man could put onto little sheets of paper. Por que fue sensible, the woman despairing in the darkness of her cell, guilty and always alone, awaiting the death with which the State would avenge the murder of her husband. The prisoners trying and failing to sleep under the thick, atrocious stone arches. ¡Que se la llevaron! ("They carried her off!"): the young woman carried off by thugs, one possibly a priest, her little shoes sticking incongruously up as the abductors bend silently to their work. Tántalo ("Tantalus"): an oldish man, hands clasped, rocking to and fro beside the knife-edge of a pyramid in a despair too deep for words, and, across his knees, the corpse-rigid form of a beautiful and much younger woman whose passion cannot be aroused by his impotence. I could not imagine feeling like this man-being fourteen, a virgin, and full of bottled-up testosterone, I didn't even realize that impotence could happen but Goya made me feel it. How could anyone do so? What hunger was it that I didn't know about but he did?

And then there was the Church, dominant anxiety of Goya's life and of mine. Nobody I knew about in Australia in the early 1950s would have presumed to criticize the One, Holy, Roman and Apostolic Church with the ferocity and zeal that Goya brought to the task at the end of the eighteenth century. In my boyhood all Catholicism was right-wing, conservative, and hysterically subservient to that most white-handedly authoritarian of recent popes, Pius XII, with his foolish cult of the Virgin of Fatima and the Assumption. In Goya's time the obsession with papal authority, and the concomitant power of the Church, was even greater, and to openly criticize either in Spain was not devoid of risk. I remember how my Jesuit teachers (very savvy men) used to say "We don't try to justify the Inquisition anymore, we just ask you to see it in its historical

context"-as though the dreadful barbarity of one set of customs excused, or at least softened, the horrors of another; as though hanging and quartering people for secular reasons somehow made comprehensible the act of burning an old woman at the stake in Seville because her neighbors had testified to Inquisitors from the Holy Office that she had squatted down, cackling, and laid eggs with cabbalistic designs on them. It seemed to us schoolboys back in the fifties that, however bad and harshly enforced they were, the terrors of Torquemada and the Holy Office could hardly have compared with those of the Gulag and the Red brainwashers in Korea. But they looked awful all the same, and they inserted one more lever into the crack that would eventually rive my Catholic faith. So it may be said that Goya-in his relentless (though, as we shall see, already somewhat outdated) attacks on the Inquisition, the greed and laziness of monks, and the exploitive nature of the monastic life-had a spiritual effect on me, and was the only artist ever to do so in terms of formal religion. He helped turn me into an ex-Catholic, an essential step in my growth and education (and in such spiritual enlightenment as I may tentatively claim), and I have always been grateful for that. The thought that, among the scores of artists of some real importance in Europe in the late eighteenth century, there was at least one man who could paint with such realism and skepticism, enduring for his pains an expatriation that turned into final exile, was confirming.

Artists are rarely moral heroes and should not be expected to be, any more than plumbers or dog breeders are. Goya, being neither madman nor masochist, had no taste for martyrdom. But he sometimes was heroic, particularly in his conflicted relations with the last Bourbon monarch he served, the odious and arbitrarily cruel Fernando VII. His work asserted that men and women should be free from tyranny and superstition; that torture, rape, despoliation, and massacre, those perennial props of power in both the civil and the religious arena, were intolerable; and that those who condoned or employed them were not to be trusted, no matter how seductive the bugle calls and the swearing of allegiance might seem. At fifteen, to find this voice-so finely wrought and yet so raw, public and yet strangely private-speaking to me with such insistence and urgency from a remote time and a country I'd never been to, of whose language I spoke not a word, was no small thing. It had the feeling of a message transmitted with terrible urgency, mouth to ear: this is the truth, you must know this, I have been through it. Or, as Goya scratched at the bottom of his copperplates in Los desastres de la guerra: "Yo lo vi," "I saw it." "It" was unbelievably strange, but the "yo" made it believable.

A European might not have reacted to Goya's portrayal of war in quite this way; these scenes of atrocity and misery would have been more familiar, closer to lived experience. War was part of the common fate of so many English, French, German, Italian, and Balkan teenagers, not just a picture in a frame. The crushed house, the dismembered body, the woman howling in her unappeasable grief over the corpse of her baby, the banal whiskered form of the rapist in a uniform suddenly looming in the doorway, the priest (or rabbi) spitted like a pig on a pike. These were things that happened in Europe, never to us, and our press did not print photographs of them. We Australian boys whose childhood lay in the 1940s had no permanent atrocity exhibition, no film of real-life terror running in our heads. Like our American counterparts we had no experience of bombing, strafing, gas, enemy invasion, or occupation. In fact, we Australians were far more innocent of such things, because we had nothing in our history comparable to the fratricidal slaughters of the American Civil War, which by then lay outside the experience of living Americans but decidedly not outside their collective memory. Except for one Japanese air strike against the remote northern city of Darwin, a place where few Australians had ever been, our mainland was as virginal as that of North America. And so the mighty cycle of Goya's war etchings, scarcely known in the country of my childhood, came from a place so unfamiliar and obscure, so unrelated to life as it was lived in that peculiar womb of nonhistory below the equator, that it demanded special scrutiny. Not Beethoven's Muss es sein-"Must it be so? It must be so"-written at the head of the last movement of his F Major String Quartet in 1826. Rather, "Can it be so? It can be so!"-a prolonged gasp of recognition at the sheer, blood-soaked awfulness of the world. Before Goya, no artist had taken on such subject matter at such depth. Battles had been formal affairs, with idealized heroes hacking at one another but dying noble and even graceful deaths: Sarpedon's corpse carried away from Troy to the broad and fertile fields of an afterlife in Lycia by Hypnos and Thanatos, Sleep and Death. Or British General Wolfe expiring instructively on the heights of Quebec, setting a standard of nobly sacrificial death etiquette for his officers and even for an Indian. Not the mindless and terrible slaughter that, Goya wanted us all to know, is the reality of war, ancient or modern.

What person whose life is involved with the visual arts, as mine has been for some forty-five years, has not thought about Goya? In the nineteenth century (as in any other) there are certain artists whose achievement is critical to an assessment of our own perhaps less urgent doings. Not to know them is to be illiterate, and we cannot exceed their perceptions. They give their times a face, or rather a thousand faces. Their experience watches ours, and can outflank it with the intensity of its feeling. A writer on music who had not thou...

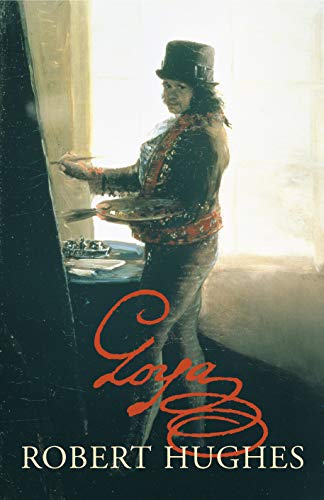

"Robert Hughes s Goya manages, with his usual style and skill, to enter into the spirit of the most enigmatic of painters." (Colm Toibin, New Statesman)

"an urbane, scholarly, immensely readable book that not only throws light on the artist s independent brilliance but also, in Hughes s wry and trenchant style, on the boorish parochialism of 18th-century Spain." (Sue Hubbard, The Independent)

"an enthralling and illuminating - if uncharacteristically deferential - study..." (Michael Kerrigan, The Scotsman)

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurHarvill Secker

- Date d'édition2003

- ISBN 10 1843430541

- ISBN 13 9781843430544

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Nombre de pages432

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,29

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Goya

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard1843430541

Goya

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_1843430541

Goya

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover1843430541

Goya

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think1843430541