Articles liés à A History of Reading

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

The fate of every book is mysterious, especially to its author. After the first publication of A History of Reading in 1996, I was astonished to discover a worldwide community of readers who, individually and under circumstances very different from my own, had undertaken the same adventures and shared with me identical rituals of initiation, epiphanies and persecutions, as well as the intuition that book and world are reflections of each other.

Reading has always been for me a sort of practical cartography. Like other readers, I have an absolute trust in the capability that reading has to map my world. I know that on a page somewhere on my shelves, staring down at me now, is the question I’m struggling with today, put into words long ago, perhaps, by someone who could not have known of my existence. The relationship between a reader and a book is one that eliminates the barriers of time and space and allows for what Francisco de Quevedo, in the sixteenth century, called “conversations with the dead”. In those conversations I’m revealed. They shape me and lend me a certain magical power.

Only a few centuries after the invention of writing, some six thousand years ago, in a forgotten corner of Mesopotamia (as the following pages will tell), the few who possessed the ability to decipher written words were known as scribes, not as readers. Perhaps the reason for this was to lend less emphasis to the greatest of their gifts: having access to the archives of human memory and rescuing from the past the voice of our experience. Since those distant beginnings, the power of readers has produced in their societies all manner of fears: for having the craft of bringing back to life a message from the past, for creating secret spaces which no one else can enter while the reading takes place, for being able to redefine the universe and rebel against unfairness, all by means of a certain page. Of these miracles we are capable, we the readers, and these may perhaps help rescue us from the abjection and stupidity to which we seem so often condemned.

And yet, banality is tempting. To dissuade us from reading, we invent strategies of distraction that transform us into bulimic consumers for whom novelty and not memory is essential. We reward triviality and monetary ambition while stripping the intellectual act of its prestige, we replace ethical and aesthetic notions with purely financial values and we propose entertainments that offer immediate gratification and the illusion of universal chatting instead of the pleasurable challenge and amiable slow pace of reading. We oppose the printing press to the electronic screen, and we substitute libraries of paper, rooted in time and space, with almost infinite webs whose most notorious qualities are instantaneity and immoderation.

Such oppositions are not new. Towards the end of the fifteenth century, in Paris, high up in the tall bell towers where Quasimodo hides, in a monk’s cell that serves both as study and alchemist’s laboratory, the archdeacon Claude Frollo stretches one hand towards the printed volume on his desk, and with the other points towards the Gothic contours of Notre Dame which he can see below him, through his window. “This,” says the unhappy clergyman, “will kill that.” According to Frollo, a contemporary of Gutenberg, the printed book will destroy the book-edifice; the printing press will put an end to the literate medieval architecture in which every column, every architrave, every portal is a text that can and must be read.

Then, as today, this prophecy was of course a false one. Five centuries later, and thanks to the printed book, we have access to the knowledge of the medieval architects, commented on by Viollet-le-Duc and John Ruskin, and re-imagined by Le Corbusier and Frank Gehry. Frollo fears that the new technology will annihilate the preceding one; he forgets that our creative capacities are prodigious and that we can always find use for yet another instrument. We don’t lack ambition.

Those who set up oppositions between the electronic technology and that of the printing press perpetuate Frollo’s fallacy. They want us to believe that the book — an instrument as perfect as the wheel or the knife, capable of holding memory and experience, an instrument that is truly interactive, allowing us to begin and end a text wherever we choose, to annotate in the margins, to give its reading a rhythm at will — should be discarded in favour of a newer tool. Such intransigent choices result in technocratic extremism. In an intelligent world, electronic devices and printed books share the space of our work desks and offer each of us different qualities and reading possibilities. Context, whether intellectual or material, matters, as most readers know.

Sometime in the early centuries of the Common Era, there appeared a curious text purporting to be a biography of Adam and Eve. Readers have always liked to imagine a prehistory or a sequel to their favourite stories, and the stories of the Bible are no exception. Taking as its starting-point the few pages of the Book of Genesis that refer to our legendary ancestors, an anonymous scribe composed a Life of Adam and Eve recounting their adventures and (mostly) misadventures after the banishment from Eden. At the end of the book, in one of those post-modernist twists so common in our earliest literatures, Eve asks her son Seth to write down a true account of his parents’ lives: the book the reader holds in his hands is that account. What Eve says to Seth is this: “But listen to me, my children! Make tablets of stone and others of clay, and write on them, all my life and your father’s and all that you have heard and seen from us. If by water the Lord judge our race, the tablets of clay will be dissolved and the tablets of stone will remain; but if by fire, the tablets of stone will be broken up and the tablets of clay will be baked [hard].” Eve wisely does not choose between tablets of stone and tablets of clay: the text may be the same, but each substance lends it a different quality, and she wants both.

Almost twenty years have elapsed since I finished (or abandoned) A History of Reading. At the time, I thought I was exploring the act of reading, the perceived characteristics of the craft and how these came into being. I didn’t know I was in fact affirming our right as readers to pursue our vocation (or passion) beyond economic, political and technological concerns, in a boundless, imaginative realm where the reader is not forced to choose and, like Eve, can have it all. Literature is not dogma: it offers questions, not conclusive answers. Libraries are essentially places of intellectual freedom: any constraints imposed upon them are our own. Reading is, or can be, the open-ended means by which we come to know a little more about the world and about ourselves, not through opposition but through recognition of words addressed to us individually, far away, and long ago. I would feel satisfied if my History of Reading were read as the grateful confession of a passionate reader, anxious to share with others this ongoing, painstaking happiness.

— Alberto Manguel, New Year’s Day, 2014

PLATES, PAGE 2

A universal fellowship of readers. From left to right, top to bottom: the young Aristotle by Charles Degeorge, Virgil by Ludger tom Ring the Elder, Saint Dominic by Fra Angelico, Paolo and Francesca by Anselm Feuerbach, two Islamic students by an anonymous illustrator, the Child Jesus lecturing in the Temple by disciples of Martin Schongauer, the tomb of Valentine Balbiani by Germain Pilon, Saint Jerome by a follower of Giovanni Bellini, Erasmus in his study by an unknown engraver.

THE LAST

PAGE

Read in order to live.

GUSTAVE FLAUBERT

Letter to Mlle de Chantepie, June 1857

THE LAST PAGE

ne hand limp by his side, the other to his brow, the young Aristotle languidly reads a scroll unfurled on his lap, sitting on a cushioned chair with his feet comfortably crossed. Holding a pair of clip glasses over his bony nose, a turbaned and bearded Virgil turns the pages of a rubricated volume in a portrait painted fifteen centuries after the poet’s death. Resting on a wide step, his right hand gently holding his chin, Saint Dominic is absorbed in the book he holds unclasped on his knees, deaf to the world. Two lovers, Paolo and Francesca, are huddled under a tree, reading a line of verse that will lead them to their doom: Paolo, like Saint Dominic, is touching his chin with his hand; Francesca is holding the book open, marking with two fingers a page that will never be reached. On their way to medical school, two Islamic students from the twelfth century stop to consult a passage in one of the books they are carrying. Pointing to the right-hand page of a book open on his lap, the Child Jesus explains his reading to the elders in the Temple while they, astonished and unconvinced, vainly turn the pages of their respective tomes in search of a refutation.

Beautiful as when she was alive, watched by an attentive lap-dog, the Milanese noblewoman Valentina Balbiani flips through the pages of her marble book on the lid of a tomb that carries, in bas-relief, the image of her emaciated body. Far from the busy city, amid sand and parched rocks, Saint Jerome, like an elderly commuter awaiting a train, reads a tabloid-sized manuscript while, in a corner, a lion lies listening. The great humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus shares with his friend Gilbert Cousin a joke in the book he is reading, held open on the lectern in front of him. Kneeling among oleander blossoms, a seventeenth-century Indian poet strokes his beard as he reflects on the verses he’s just read out loud to himself to catch their full flavour, clasping the preciously bound book in his left hand. Standing next to a long row of roughly hewn shelves, a Korean monk pulls out one of the eighty thousand wooden tablets of the seven-centuries-old Tripitaka Koreana and holds it in front of him, reading with silent attention. “Study To Be Quiet” is the advice given by the unknown stained-glass artist who portrayed the fisherman and essayist Izaak Walton reading a little book by the shores of the River Itchen near Winchester Cathedral.

From left to right, top to bottom: a Mogul poet by Muhammad Ali, the library at the Haeinsa Temple in Korea, Izaak Walton by an anonymous nineteenth-century English artist, Mary Magdalene by Emmanuel Benner, Dickens giving a reading, a young man on the Paris quais.

Stark naked, a well-coiffed Mary Magdalen, apparently unrepentant, lies on a cloth strewn over a rock in the wilderness, reading a large illustrated volume. Drawing on his acting talents, Charles Dickens holds up a copy of one of his own novels, from which he is going to read to an adoring public. Leaning on a stone parapet overlooking the Seine, a young man loses himself in a book (what is it?) held open in front of him. Impatient or merely bored, a mother holds up a book for her red-haired son as he tries to follow the words with his right hand on the page. The blind Jorge Luis Borges screws up his eyes the better to hear the words of an unseen reader. In a dappled forest, sitting on a mossy trunk, a boy holds in both hands a small book from which he’s reading in soft quiet, master of time and of space.

From left to right: a mother teaching her son to read by Gerard ter Borch, Jorge Luis Borges by Eduardo Comesaña, a forest scene by Hans Toma.

All these are readers, and their gestures, their craft, the pleasure, responsibility and power they derive from reading, are common with mine.

I am not alone.

I first discovered that I could read at the age of four. I had seen, over and over again, the letters that I knew (because I had been told) were the names of the pictures under which they sat. The boy drawn in thick black lines, dressed in red shorts and a green shirt (that same red and green cloth from which all the other images in the book were cut, dogs and cats and trees and thin tall mothers), was also somehow, I realized, the stern black shapes beneath him, as if the boy’s body had been dismembered into three clean-cut figures: one arm and the torso, b; the severed head so perfectly round, o; and the limp, low-hanging legs, y. I drew eyes in the round face, and a smile, and filled in the hollow circle of the torso. But there was more: I knew that not only did these shapes mirror the boy above them, but they also could tell me precisely what the boy was doing, arms stretched out and legs apart. The boy runs, said the shapes. He wasn’t jumping, as I might have thought, or pretending to be frozen into place, or playing a game whose rules and purpose were unknown to me. The boy runs.

And yet these realizations were common acts of conjuring, less interesting because someone else had performed them for me. Another reader — my nurse, probably — had explained the shapes and now, every time the pages opened to the image of this exuberant boy, I knew what the shapes beneath him meant. There was pleasure in this, but it wore thin. There was no surprise.

Then one day, from the window of a car (the destination of that journey is now forgotten), I saw a billboard by the side of the road. The sight could not have lasted very long; perhaps the car stopped for a moment, perhaps it just slowed down long enough for me to see, large and looming, shapes similar to those in my book, but shapes that I had never seen before. And yet, all of a sudden, I knew what they were; I heard them in my head, they metamorphosed from black lines and white spaces into a solid, sonorous, meaningful reality. I had done this all by myself. No one had performed the magic for me. I and the shapes were alone together, revealing ourselves in a silently respectful dialogue. Since I could turn bare lines into living reality, I was all-powerful, I could read.

What that word was on the long-past billboard I no longer know (vaguely I seem to remember a word with several As in it), but the impression of suddenly being able to comprehend what before I could only gaze at is as vivid today as it must have been then. It was like acquiring an entirely new sense, so that now certain things no longer consisted merely of what my eyes could see, my ears could hear, my tongue could taste, my nose could smell, my fingers could feel, but of what my whole body could decipher, translate, give voice to, read.

The readers of books, into whose family I was unknowingly entering (we always think that we are alone in each discovery, and that every experience, from death to birth, is terrifyingly unique), extend or concentrate a function common to us all. Reading letters on a page is only one of its many guises. The astronomer reading a map of stars that no longer exist; the Japanese architect reading the land on which a house is to be built so as to guard it from evil forces; the zoologist reading the spoor of animals in the forest; the card-player reading her partner’s gestures before playing the winning card; the dancer reading the choreographer’s notatio...

“Ingenious...a veritable museum of literacy. One feels envious of his passion...through it, his gift becomes our own.”—The New York Times Book Review

“Manguel has taken on the daunting subject of our own passion for books and succeeded in turning it into a passionate book of his own.”—Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

“No one who follows Manguel’s narrative to its conclusion need ever again feel guilty about putting off errands, chores, the bills, the kids, sleep—whatever—and curling up with a good, or even a great, book.”—Newsweek

“Manguel is a generous companion...he remains, in the proper sense of the word, an ‘amateur,’ a lover rather than a specialist.”—George Steiner, the New Yorker

“Richly detailed and utterly fascinating...what lifts A History of Reading above mere charm and idiosyncrasy is Manguel’s reader’s soul. A few hours passed with [his] book will remind anyone who needs reminding that an astonishing bond exists between word and world.”—Sven Birkerts, Boston Magazine

“A highly entertaining overview that leaves us with both a new appreciation of our own bibliomania and a deeper understanding of the role that the written word has played throughout history.”—The New York Times

“Manguel’s digressions are delightful, his anecdotes appealing, and his stories scintillating. What might have been no more than one dammed thing after another turns out to be, at the handsof this splendid raconteur, one divine thing after another....It is all utterly beguiling.”—The Boston Sunday Globe

“Impressionistic, engrossing.”—Time

“An entertaining, provocative, and informative book.”—The Washington Post

“Tickles, surprises, and amuses.”—The Philadelphia Inquirer

“Impressive, engaging.”—The Washington Times

“Erudite and original.”—The Miami Herald

“Enormously entertaining.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“A wonderful merger of scholarship and personal essay....Manguel writes so beautifully and felicitously that he infects us with enthusiasm again and again.”—Philip Lopate

“Manguel’s urbane, unpretentious tone recalls that of a friend eager to share his knowledge and enthusiasm. His book, digressive, witty, surprising, is a pleasure.”—Kirkus

“Highly enjoyable....I finished the book with a sense of gratitude to have shared this journey through time in the company of a mind so lively, knowledgeable, and sympathetic.”—P. D. James

“An eclectic and deeply felt history of reading. It is a history illuminated by an acute sensibility....An unfailingly engaging work.”—School Library Journal

“Unique, enlightening, and as captivating as a celebration of reading should be.”—Booklist

“Interesting, intriguing, and entertaining.”—Library Journal

“Erudition and memoir are beautifully wed in this stimulating and provocative book.”—Virginia Quarterly Review

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

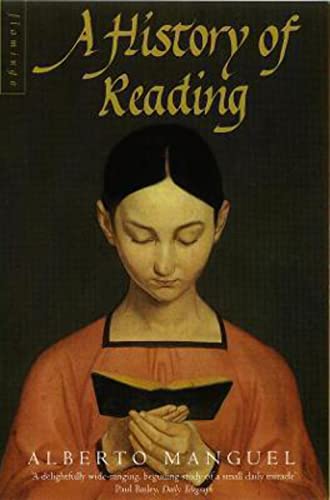

- ÉditeurFlamingo

- Date d'édition1997

- ISBN 10 0006546811

- ISBN 13 9780006546818

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages384

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 5,26

De Royaume-Uni vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

A History of Reading

Description du livre paperback. Etat : New. Language: ENG. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780006546818

History of Reading

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 1369944-n

A History of Reading

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0006546811

A History of Reading [Soft Cover ]

Description du livre Soft Cover. Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780006546818

A History of Reading

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0006546811

History of Reading

Description du livre Etat : New. 1997. 1st. Paperback. This history of reading goes from the earliest examples of the clay tablets and cuneiform of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt to today's digital revolution. It argues that it is the demands of the reader, acting alongside the will of the writer, that is the evolutionary motor of literary genres. Num Pages: 384 pages, 140 b&w illustrations. BIC Classification: CFF; GL. Category: (G) General (US: Trade). Dimension: 232 x 166 x 25. Weight in Grams: 630. . . . . . N° de réf. du vendeur V9780006546818

A History of Reading

Description du livre Etat : New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. N° de réf. du vendeur bk0006546811xvz189zvxnew

A History of Reading

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0006546811

A History of Reading

Description du livre Paperback / softback. Etat : New. New copy - Usually dispatched within 4 working days. This history of reading goes from the earliest examples of the clay tablets and cuneiform of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt to today's digital revolution. It argues that it is the demands of the reader, acting alongside the will of the writer, that is the evolutionary motor of literary genres. N° de réf. du vendeur B9780006546818

A History of Reading

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : Brand New. 384 pages. 8.43x6.26x1.02 inches. In Stock. N° de réf. du vendeur __0006546811