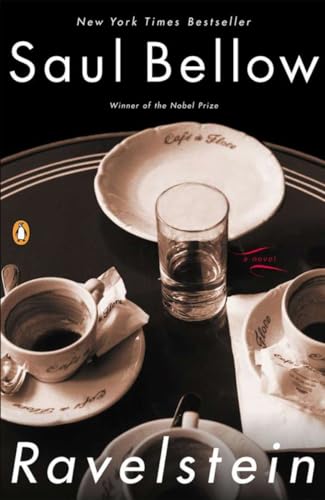

Ravelstein - Couverture souple

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Odd that mankind's benefactors should be amusing people. In America at least this is often the case. Anyone who wants to govern the country has to entertain it. During the Civil War people complained about Lincoln's funny stories. Perhaps he sensed that strict seriousness was far more dangerous than any joke. But critics said that he was frivolous and his own Secretary of War referred to him as an ape.

Among the debunkers and spoofers who formed the tastes and minds of my generation H. L. Mencken was the most prominent. My high school friends, readers of the American Mercury, were up on the Scopes trial as Mencken reported it. Mencken was very hard on William Jennings Bryan and the Bible Belt and Boobus Americanus. Clarence Darrow, who defended Scopes, represented science, modernity, and progress. To Darrow and Mencken, Bryan the Special Creationist was a doomed Farm Belt absurdity. In the language of evolutionary theory Bryan was a dead branch of the life-tree. His Free Silver monetary standard was a joke. So was his old-style congressional oratory. So were the huge Nebraska farm dinners he devoured. His meals, Mencken said, were the death of him. His views on Special Creation were subjected to extreme ridicule at the trial, and Bryan went the way of the pterodactyl—the clumsy version of an idea which later succeeded—the gliding reptiles becoming warm-blooded birds that flew and sang.

I filled up a scribbler with quotes from Mencken and later added notes from spoofers or self-spoolers like W. C. Fields or Charlie Chaplin, Mae West, Huey Long, and Senator Dirksen. There was even a page on Machiavelli's sense of humor. But I'm not about to involve you in my speculations on wit and self-irony in democratic societies. Not to worry. I'm glad my old scribbler has disappeared. I have no wish to see it again. It surfaces briefly as a sort of extended footnote.

I have always had a weakness for footnotes. For me a clever or a wicked footnote has redeemed many a text. And I see that I am now using a long footnote to open a serious subject—shifting in a quick move to Paris, to a penthouse in the Hotel Crillon. Early June. Breakfast time. The host is my good friend Professor Ravelstein, Abe Ravelstein. My wife and I, also staying at the Crillon, have a room below, on the sixth floor. She is still asleep. The entire floor below ours (this is not absolutely relevant but somehow I can't avoid mentioning it) is occupied just now by Michael Jackson and his entourage. He performs nightly in some vast Parisian auditorium. Very soon his French fans will arrive and a crowd of faces will be turned upward, shouting in unison, Miekell Jack-sown. A police barrier holds the fans back. Inside, from the sixth floor, when you look down the marble stairwell you see Michael's bodyguards. One of them is doing the crossword puzzle in the Paris Herald.

"Terrific, isn't it, having this pop circus?" said Ravelstein. The Professor was very happy this morning. He had leaned on the management to put him into this coveted suite. To be in Paris—at the Crillon. To be here for once with plenty of money. No more of the funky rooms at the Dragon Volant, or whatever they called it, on the rue du Dragon; or in the Hotel de l'Académie on the rue des Saints Pères facing the medical college. Hotels don't come any grander or more luxurious than the Crillon, where the top American brass had been quartered during the peace negotiations after the First World War.

"Great, isn't it?" said Ravelstein, with one of his rapid gestures.

I confirmed that it was. We had the center of Paris right below us—the place de la Concorde with the obelisk, the Orangerie, the Chambre des Députés, the Seine with its pompous bridges, palaces, gardens. Of course these were great things to see, but they were greater today for being shown from the penthouse by Ravelstein, who only last year had been a hundred thousand dollars in debt. Maybe more. He used to joke with me about his "sinking fund."

He would say, "I'm sinking with it—do you know what the term means in financial circles, Chick?"

"Sinking fund? I have a rough idea."

Nobody in the days before he struck it rich had ever questioned Ravelstein's need for Armani suits or Vuitton luggage, for Cuban cigars, unobtainable in the U.S., for the Dunhill accessories, for solid-gold Mont Blanc pens or Baccarat or Lalique crystal to serve wine in—or to have it served. Ravelstein was one of those large men—large, not stout—whose hands shake when there are small chores to perform. The cause was not weakness but a tremendous eager energy that shook him when it was discharged.

Well, his friends, colleagues, pupils, and admirers no longer had to ante up in support of his luxurious habits. Thank God, he could now do without the elaborate trades among his academic pals in Jensen silver, or Spode or Quimper. All of that was a thing of the past. He was now very rich. He had gone public with his ideas. He had written a book—difficult but popular—a spirited, intelligent, warlike book, and it had sold and was still selling in both hemispheres and on both sides of the equator. The thing had been done quickly but in real earnest: no cheap concessions, no popularizing, no mental monkey business, no apologetics, no patrician airs. He had every right to look as he looked now, while the waiter set up our breakfast. His intellect had made a millionaire of him. It's no small matter to become rich and famous by saying exactly what you think—to say it in your own words, without compromise.

This morning Ravelstein wore a blue-and-white kimono. It had been presented to him in Japan when he lectured there last year. He had been asked what would particularly please him and he said he would like a kimono. This one, fit for a shogun, must have been a special order. He was very tall. He was not particularly graceful. The great garment was loosely belted and more than half open. His legs were unusually long, not shapely. His underpants were not securely pulled up.

"The waiter tells me that Michael Jackson won't eat the Crillon's food," he said. "His cook flies everywhere with him in the private jet. Anyhow, the Crillon chef's nose is out of joint. His cookery was good enough for Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, he says, and also a whole slew of shahs, kings, generals, and prime ministers. But this little glamour monkey refuses it. Isn't there something in the Bible about crippled kings living under the table of their conqueror—feeding on what falls to the floor?"

"I think there is. I recall that their thumbs had been cut off. But what's that got to do with the Crillon or Michael Jackson?"

Abe laughed and said he wasn't sure. It was only something that went through his head. Up here, the treble voices of the fans, Parisian adolescents—boys and girls shouting in unison—were added to the noises of buses, trucks, and taxis.

This historic show was our background. We were having a good time over our coffee. Ravelstein was in high spirits. Nevertheless, we kept our voices low because Nikki, Abe's companion, was still sleeping. It was Nikki's habit, back in the U.S., to watch kung fu films from his native Singapore until four o'clock in the morning. Here too he was up most of the night. The waiter had rolled shut the sliding doors so that Nikki's silken sleep should not be disturbed. I glanced through the window from time to time at his round arms and the long shifting layers of black hair reaching his glossy shoulders. In his early thirties, handsome Nikki was boyish still.

The waiter had entered with wild strawberries, brioches, jam jars, and small pots of what I had been brought up to call hotel silver. Ravelstein scribbled his name wildly on the check while bringing a bun to his mouth. I was the neater eater. Ravelstein when he was feeding and speaking made you feel that something biological was going on, that he was stoking his system and nourishing his ideas.

This morning he was again urging me to go more public, to get away from the private life, to take an interest in "public life, in politics," to use his own words. He wanted me to try my hand at biography, and I had agreed to do it. At his request, I had written a short account of J. M. Keynes's description of the arguments over German reparations and the lifting of the Allied blockade in 1919. Ravelstein was pleased with what I had done but not quite satisfied as yet. He thought I had a rhetorical problem. I said that too much emphasis on the literal facts narrowed the wider interest of the enterprise.

I may as well come out with it: I had a high school English teacher named Morford ("Crazy Morford" we called him) who had us reading Macaulay's essay on Boswell's Johnson. Whether this was Morford's own idea or an item in the curriculum set by the Board of Education, I can't say. Macaulay's essay, commissioned in the nineteenth century by the Encyclopedia Britannica, was published in an American textbook edition by the Riverside Press. Reading it put me into a purple fever. Macaulay exhilarated me with his version of the Life, with the "anfractuosity" of Johnson's mind. I have since read many sober criticisms of Macaulay's Victorian excesses. But I have never been cured—I never wanted to be cured of my weakness for Macaulay. Thanks to him I still see poor convulsive Johnson touching every lamppost on the street and eating spoiled meat and rancid puddings.

What line to take in writing a biography became the problem. There was Johnson's own example in the memoir of his friend Richard Savage. There was Plutarch, of course. When I mentioned Plutarch to a Greek scholar, he put him down as "a mere litterateur." But without Plutarch could Antony and Cleopatra have been written?

Next I considered Aubrey's Brief Lives.

But I shan't go through the whole list.

I had tried to describe Mr. Morford to Ravelstein: Crazy Morford was never downright drunk in class, but he obviously was a lush—he had a drunkard's red face. He wore the same fire-sale suit every day. He didn't want to know you, he didn't want to be known by you. His blue abstract alcoholic look was never directed at anyone. Under his disorderly brow he fixed his stare only at the walls, through the windows, into the book he was reading. Macaulay's Johnson and Shakespeare's Hamlet were the two works we studied with him that term. Johnson, despite his scrofula, his raggedness, his dropsy, had his friendships, wrote his books just as Morford met his classes, listened to us as we recited from memory the lines "How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable seem to me all the uses of this world." His grim cropped head, his fiery face, his hand clasped behind his back. Altogether flat and unprofitable.

Ravelstein wasn't much interested in my description of him. Why did I invite him to see the Morford I remembered? But Abe was right to put me onto the Keynes essay. Keynes, the powerful economist-statesman whom everybody knows for The Economic Consequences of the Peace, sent letters and memoranda to his Bloomsbury friends reporting on his postwar experiences, in particular the reparations debates between the defeated Germans and the Allied leaders—Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and the Americans. Ravelstein, a man not free with his praises, said that this time I had written a first-class account of Keynes's notes to his friends. Ravelstein rated Hayek higher than Keynes as an economist. Keynes, he said, had exaggerated the harshness of the Allies and played into the hands of the German generals and eventually of the Nazis. The Peace of Versailles was far less punitive than it ought to have been. The war aims of Hitler in 1939 were no different from those of the Kaiser in 1914. But setting this serious error aside, Keynes had a great many personal attractions. Educated at Eton and Cambridge, he was polished socially and culturally by the Bloomsbury group. The Great Politics of his day had developed and perfected him. I suppose in his personal life he considered himself a Uranian—a British euphemism for homosexual. Ravelstein mentioned that Keynes had married a Russian ballerina. He also explained to me that Uranus had fathered Aphrodite but that she had had no mother. She was conceived by the sea foam. He would say such things not because he thought I was ignorant of them but because he judged that I needed at a given moment to have my thoughts directed toward them. So he reminded me that when Uranus was killed by the Titan Cronus, his seed spilled into the sea. And this somehow had to do with reparations, or with the fact that the still blockaded Germans just then were starving.

Ravelstein, who for reasons of his own put me on to Keynes's paper, best remembered the passages describing the German bankers' inability to meet the demands of France and England. The French were after the Kaiser's gold reserves; they said the gold must be handed over at once. The English said they would settle for hard currencies. One of the German negotiators was a Jew. Lloyd George, losing his temper, turned on this man: he did an astonishing kike number on him, crouching, hunching, limping, spitting, zizzing his esses, sticking out his backside, doing a splayfoot parody of a Jew-walk. All this was described by Keynes to his Bloomsbury friends. Ravelstein didn't think well of the Bloomsbury intellectuals. He disliked their high camp, he disapproved of queer antics and of what he called "faggot behavior." He couldn't and didn't fault them for gossiping. He himself loved gossip too well to do that. But he said they were not thinkers but snobs, and their influence was pernicious. The spies later recruited in England by the GPU or the NKVD in the thirties were nurtured by Bloomsbury.

"But you did that well, Chick, about Lloyd George's nasty youpin parody."

Youpin is the French for "kike."

"Thank you," I said.

"I wouldn't dream of meddling," said Ravelstein. "But I think you'd agree that I'm trying to do you some good."

Of course I understood his motive. He wanted me to write his biography and at the same time he wanted to rescue me from my pernicious habits. He thought I was stuck in privacy and should be restored to community. "Too many years of inwardness!" he used to say. I badly needed to be in touch with politics—not local or machine politics, nor even national politics, but politics as Aristotle or Plato understood the term, rooted in our nature. You can't turn your back on your nature. I admitted to Ravelstein that reading those Keynes documents and writing the piece had been something like a holiday. Rejoining humankind, taking a humanity bath. There are times when I need to ride in the subway at rush hour or sit in a crowded movie house—that's what I mean by a humanity bath. As cattle must have salt to lick, I sometimes crave physical contact.

"I have some unclassified notions about Keynes and the World Bank, his Bretton Woods agreement, and also his attack on the Treaty of Versailles. I know just enough about Keynes to fit his name into a crossword puzzle," I said. "I'm glad you brought his private memoranda to my attention. His Bloomsbury friends must have been dying to have his impressions of the Peace Conference. Thanks to him they had world-historical ringside seats. And I suppose Ly...

Deeply insightful and always moving, Saul Bellow's new novel is a journey through love and memory. It is brave, dark, and bleakly funny: an elegy to friendship and to lives well (or badly) lived.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurPenguin Publishing Group

- Date d'édition2001

- ISBN 10 0141001763

- ISBN 13 9780141001760

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages240

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Ravelstein (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century) by Bellow, Saul [Paperback ]

Description du livre Soft Cover. Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780141001760

Ravelstein (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century)

Description du livre Etat : New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition 0.45. N° de réf. du vendeur bk0141001763xvz189zvxnew

Ravelstein (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century)

Description du livre Etat : New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.45. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-0141001763-new

Ravelstein

Description du livre Etat : New. pp. 233 Reissued Edition. N° de réf. du vendeur 26661017

Ravelstein (Paperback or Softback)

Description du livre Paperback or Softback. Etat : New. Ravelstein 0.42. Book. N° de réf. du vendeur BBS-9780141001760

Ravelstein

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur 490342-n

Ravelstein (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century)

Description du livre Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur I-9780141001760

Ravelstein

Description du livre Etat : New. pp. 233. N° de réf. du vendeur 8235462

Ravelstein (Paperback)

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Paperback. Abe Ravelstein is a brilliant professor at a prominent midwestern university and a man who glories in training the movers and shakers of the political world. He has lived grandly and ferociously-and much beyond his means. His close friend Chick has suggested that he put forth a book of his convictions about the ideas which sustain humankind, or kill it, and much to Ravelstein's own surprise, he does and becomes a millionaire. Ravelstein suggests in turn that Chick write a memoir or a life of him, and during the course of a celebratory trip to Paris the two share thoughts on mortality, philosophy and history, loves and friends, old and new, and vaudeville routines from the remote past. The mood turns more somber once they have returned to the Midwest and Ravelstein succumbs to AIDS and Chick himself nearly dies.Deeply insightful and always moving, Saul Bellow's new novel is a journey through love and memory. It is brave, dark, and bleakly funny: an elegy to friendship and to lives well (or badly) lived. A brilliant professor and his friend share a celebratory trip to Paris where they explore thoughts on mortality, philosophy, history, old suits, and friends old and new. The mood turns more somber once they return home and the professor succumbs to AIDS. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780141001760

Ravelstein (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century)

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0141001763