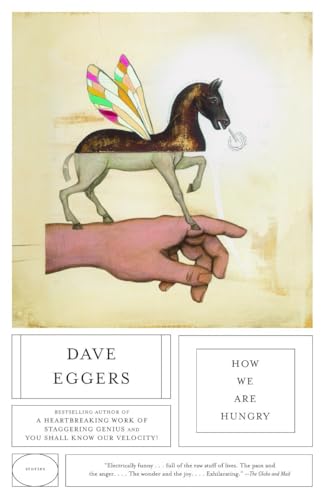

How We Are Hungry: Stories by Dave Eggers - Couverture souple

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBN

Extrait :

Another

I'd gone to Egypt, as a courier, easy. I gave the package to a guy at the airport and was finished and free by noon on the first day. It was a bad time to be in Cairo, unwise at that juncture, with the poor state of relations between our nation and the entire region, but I did it anyway because, at that point in my life, if there was a window at all, however small and discouraged, I would-

I'd been having trouble thinking, finishing things. Words like anxiety and depression seemed apt then, in that I wasn't interested in the things I was usually interested in, and couldn't finish a glass of milk without deliberation. But I didn't stop to ruminate or wallow. Diagnosis would have made it all less interesting.

I'd been a married man, twice; I'd been a man who turned forty among friends; I'd had pets, jobs in the foreign service, people working for me. Years after all that, somewhere in May, I found myself in Egypt, against the advice of my government, with mild diarrhea and alone.

There was a new heat there, dry and suffocating and unfamiliar to me. I'd lived only in humid places - Cincinnati, Hartford - where the people I knew felt sorry for each other. Surviving in the Egyptian heat was invigorating, though-living under that sun made me lighter and stronger, made of platinum. I'd dropped ten pounds in a few days but I felt good.

This was a few weeks after some terrorists had slaughtered seventy tourists at Luxor, and everyone was jittery. And I'd just been in New York, on the top of the Empire State Building, a few days after a guy opened fire there, killing one. I wasn't consciously following trouble around, but then what the hell was I doing-

On a Tuesday I was by the pyramids, walking, loving the dust, squinting; I'd just lost my second pair of sunglasses. The hawkers who work the Gizeh plateau - really some of the least charming charmers the world owns - were trying to sell me anything - little scarab toys, Cheops keychains, plastic sandals. They spoke twenty words of a dozen languages, and tried me with German, Spanish, Italian, English. I said no, feigned muteness, got in the habit of just saying "Finland!" to them all, sure that they didn't know any Finnish, until a man offered me a horseback ride, in American English, hooking his r's obscenely. They really were clever bastards. I'd already gotten a brief and expensive camel ride, which was worthless, and though I'd never ridden a horse past an amble and hadn't really wanted to, I followed him on foot.

"Through the desert," he said, leading me past a silver tourist bus, Swiss seniors unloading. I followed him. "We go get horse. We ride to the Red Pyramid," he said. I followed. "You have your horse yourself," he said, answering my last unspoken question.

I knew the Red Pyramid had just been reopened, or was about to be reopened, though I didn't know why they called it Red. I wanted to ride on a horse through the desert. I wanted to see if this man - slight, with brown teeth, wide-set eyes, a cop mustache - would try to kill me. There were plenty of Egyptians who would love to kill me, I was sure, and I was ready to engage in any way with someone who wanted me dead. I was alone and reckless and both passive and quick to fury. It was a beautiful time, everything electric and hideous. In Egypt I was noticed, I was yelled at by some and embraced by others. One day I was given free sugarcane juice by a well-dressed man who lived under a bridge and wanted to teach at an American boarding school. I couldn't help him but he was sure I could, talking to me loudly by the juice bar, outside, in crowded Cairo, while others eyed me vacantly. I was a star, a heathen, an enemy, a nothing.

At Gizeh I walked with the horse man - he had no smell - away from the tourists and buses, and down from the plateau. The hard sand went soft. We passed an ancient man in a cave below ground, and I was told to pay him baksheesh, a tip, because he was a "famous man" and the keeper of that cave. I gave him a dollar. The first man and I continued walking, for about a mile, and where the desert met a road he introduced me to his partner, a fat man, bursting from a threadbare shirt, who had two horses, both black, Arabian.

They helped me on the smaller of the two. The animal was alive everywhere, restless, its hair marshy with sweat. I didn't tell them that I'd only ridden once before, and that time at a roadside Fourth of July fair, walking around a track, half-drunk. I was trying to find dinosaur bones in Arizona - I thought, briefly, that I was an archeologist. I still don't know why I was made the way I am.

"Hesham," the horse man said, and jerked his thumb at his sternum. I nodded.

I got on the small black horse and we left the fat man. Hesham and I trotted about five miles on the rural road, newly paved, passing farms while cabs shot past us, honking. Always the honking in Cairo! - the drivers steering with the left hand to be better able, with their right, to communicate every nuance of their feelings. My saddle was simple and small; I spent a good minute trying to figure out how it was attached to the horse and how I would be attached to it. Under it I could feel every bone and muscle and band of cartilage that bound the horse together. I stroked its neck apologetically and it shook my hand away. It loathed me.

When we turned from the road and crossed a narrow gorge, the desert spread out in front of us without end. I felt like a bastard for ever doubting that it was so grand and acquiescent. It looked like a shame to step on it, it was shaped so carefully, layer upon layer of velveteen.

On the horse's first steps onto sand, Hesham said: "Yes?"

And I nodded.

With that he whipped my horse and bellowed to his own and we were at a gallop, in the Sahara, heading up a dune the size of a four-story building.

I'd never galloped before. I had no idea how to ride. My horse was flying; he seemed to like it. The last horse I'd been on had bitten me constantly. This one just thrust his head rhythmically at the future.

I slid to the back of the saddle and pulled myself forward again. I balled the reins into my hand and leaned down, getting closer to the animal's body. But something or everything was wrong. I was being struck from every angle. It was the most violence I'd experienced in years.

Hesham, seeing me struggle, slowed down. I was thankful. The world went quiet. I regained my grip on the reins, repositioned myself on the saddle, and leaned forward. I patted the horse's neck and narrowly missed his teeth, which were now attempting to eat my fingers. I felt ready again. I would know more now. The start had been chaos because it was so sudden.

"Yes?" Hesham said.

I nodded. He struck my horse savagely and we bolted.

We made it over the first dune and the view was a conqueror's, oceans upon oceans, a million beveled edges. We flew down the dune and up the next. The horse didn't slow and the saddle was punishing my spine. Holy Christ it hurt. I wasn't in sync with the horse - I tried but neither the fat man nor the odorless one I was following had given me any direction and my spine was striking the saddle with enormous force, with terrible rhythm, and soon the pain was searing, molten. I was again and again being dropped on my ass, on marble, from a hundred feet-

I could barely speak enough to tell Hesham to slow down, to stop, to rest my spine. Something was being irrevocably damaged, I was sure. But there was no way to rest. I couldn't get a word out. I struggled for air, I tried to ride higher in the saddle, but couldn't stop because I had to show Hesham I was sturdy, unshrinking. He was glancing back at me periodically and when he did I squinted and smiled in the hardest way I could.

Soon he slowed again. We trotted for a few minutes. The pounding on my spine stopped. The pain subsided. I was so thankful. I took in as much air as I could.

"Yes?" Hesham said.

I nodded.

And he struck my horse again and we galloped.

The pain resumed, with more volume, subtleties, tendrils reaching into new and unknown places - shooting through to my clavicles, armpits, neck. I was intrigued by the newness of the torment and would have studied it, enjoyed it in a way, but its sudden stabbing prevented me from drawing the necessary distance from it.

I needed to prove to this Egyptian lunatic that I could ride with him. That we were equal out here, that I could keep up and devour it, the agony. That I could be punished, that I expected the punishment and could withstand it, however long he wanted to give it to me. We could ride together across the Sahara even though we hated each other for a hundred good and untenable reasons. I was part of a continuum that went back thousands of years, nothing having changed. It almost made me laugh, so I rode as anyone might have ridden at any point in history, meaning that it was only him and me and the sand and a horse and saddle - I had nothing with me at all, was wearing a white button-down shirt and shorts and sandals-and Jesus, however disgusting we were, however wrong was the space between us, we were really soaring.

And I was watching. As the horse's hooves scratched the sand and the horse breathed and I breathed, as the mane whipped over my hands and the sand sprayed over my legs, spitting on my bare ankles, I was watching how the man moved with the horse. Somewhere, after twenty minutes more of continuous pounding, with the horse at full gallop,

I learned. I had been letting the horse strike me, was trying to sit above the saddle, hoping my distance from it would diminish the impact each time, but there were ways to eliminate the pain altogether.

I learned. I moved with the horse and when I finally started moving with that damned horse, nodding forward,...

Revue de presse :

I'd gone to Egypt, as a courier, easy. I gave the package to a guy at the airport and was finished and free by noon on the first day. It was a bad time to be in Cairo, unwise at that juncture, with the poor state of relations between our nation and the entire region, but I did it anyway because, at that point in my life, if there was a window at all, however small and discouraged, I would-

I'd been having trouble thinking, finishing things. Words like anxiety and depression seemed apt then, in that I wasn't interested in the things I was usually interested in, and couldn't finish a glass of milk without deliberation. But I didn't stop to ruminate or wallow. Diagnosis would have made it all less interesting.

I'd been a married man, twice; I'd been a man who turned forty among friends; I'd had pets, jobs in the foreign service, people working for me. Years after all that, somewhere in May, I found myself in Egypt, against the advice of my government, with mild diarrhea and alone.

There was a new heat there, dry and suffocating and unfamiliar to me. I'd lived only in humid places - Cincinnati, Hartford - where the people I knew felt sorry for each other. Surviving in the Egyptian heat was invigorating, though-living under that sun made me lighter and stronger, made of platinum. I'd dropped ten pounds in a few days but I felt good.

This was a few weeks after some terrorists had slaughtered seventy tourists at Luxor, and everyone was jittery. And I'd just been in New York, on the top of the Empire State Building, a few days after a guy opened fire there, killing one. I wasn't consciously following trouble around, but then what the hell was I doing-

On a Tuesday I was by the pyramids, walking, loving the dust, squinting; I'd just lost my second pair of sunglasses. The hawkers who work the Gizeh plateau - really some of the least charming charmers the world owns - were trying to sell me anything - little scarab toys, Cheops keychains, plastic sandals. They spoke twenty words of a dozen languages, and tried me with German, Spanish, Italian, English. I said no, feigned muteness, got in the habit of just saying "Finland!" to them all, sure that they didn't know any Finnish, until a man offered me a horseback ride, in American English, hooking his r's obscenely. They really were clever bastards. I'd already gotten a brief and expensive camel ride, which was worthless, and though I'd never ridden a horse past an amble and hadn't really wanted to, I followed him on foot.

"Through the desert," he said, leading me past a silver tourist bus, Swiss seniors unloading. I followed him. "We go get horse. We ride to the Red Pyramid," he said. I followed. "You have your horse yourself," he said, answering my last unspoken question.

I knew the Red Pyramid had just been reopened, or was about to be reopened, though I didn't know why they called it Red. I wanted to ride on a horse through the desert. I wanted to see if this man - slight, with brown teeth, wide-set eyes, a cop mustache - would try to kill me. There were plenty of Egyptians who would love to kill me, I was sure, and I was ready to engage in any way with someone who wanted me dead. I was alone and reckless and both passive and quick to fury. It was a beautiful time, everything electric and hideous. In Egypt I was noticed, I was yelled at by some and embraced by others. One day I was given free sugarcane juice by a well-dressed man who lived under a bridge and wanted to teach at an American boarding school. I couldn't help him but he was sure I could, talking to me loudly by the juice bar, outside, in crowded Cairo, while others eyed me vacantly. I was a star, a heathen, an enemy, a nothing.

At Gizeh I walked with the horse man - he had no smell - away from the tourists and buses, and down from the plateau. The hard sand went soft. We passed an ancient man in a cave below ground, and I was told to pay him baksheesh, a tip, because he was a "famous man" and the keeper of that cave. I gave him a dollar. The first man and I continued walking, for about a mile, and where the desert met a road he introduced me to his partner, a fat man, bursting from a threadbare shirt, who had two horses, both black, Arabian.

They helped me on the smaller of the two. The animal was alive everywhere, restless, its hair marshy with sweat. I didn't tell them that I'd only ridden once before, and that time at a roadside Fourth of July fair, walking around a track, half-drunk. I was trying to find dinosaur bones in Arizona - I thought, briefly, that I was an archeologist. I still don't know why I was made the way I am.

"Hesham," the horse man said, and jerked his thumb at his sternum. I nodded.

I got on the small black horse and we left the fat man. Hesham and I trotted about five miles on the rural road, newly paved, passing farms while cabs shot past us, honking. Always the honking in Cairo! - the drivers steering with the left hand to be better able, with their right, to communicate every nuance of their feelings. My saddle was simple and small; I spent a good minute trying to figure out how it was attached to the horse and how I would be attached to it. Under it I could feel every bone and muscle and band of cartilage that bound the horse together. I stroked its neck apologetically and it shook my hand away. It loathed me.

When we turned from the road and crossed a narrow gorge, the desert spread out in front of us without end. I felt like a bastard for ever doubting that it was so grand and acquiescent. It looked like a shame to step on it, it was shaped so carefully, layer upon layer of velveteen.

On the horse's first steps onto sand, Hesham said: "Yes?"

And I nodded.

With that he whipped my horse and bellowed to his own and we were at a gallop, in the Sahara, heading up a dune the size of a four-story building.

I'd never galloped before. I had no idea how to ride. My horse was flying; he seemed to like it. The last horse I'd been on had bitten me constantly. This one just thrust his head rhythmically at the future.

I slid to the back of the saddle and pulled myself forward again. I balled the reins into my hand and leaned down, getting closer to the animal's body. But something or everything was wrong. I was being struck from every angle. It was the most violence I'd experienced in years.

Hesham, seeing me struggle, slowed down. I was thankful. The world went quiet. I regained my grip on the reins, repositioned myself on the saddle, and leaned forward. I patted the horse's neck and narrowly missed his teeth, which were now attempting to eat my fingers. I felt ready again. I would know more now. The start had been chaos because it was so sudden.

"Yes?" Hesham said.

I nodded. He struck my horse savagely and we bolted.

We made it over the first dune and the view was a conqueror's, oceans upon oceans, a million beveled edges. We flew down the dune and up the next. The horse didn't slow and the saddle was punishing my spine. Holy Christ it hurt. I wasn't in sync with the horse - I tried but neither the fat man nor the odorless one I was following had given me any direction and my spine was striking the saddle with enormous force, with terrible rhythm, and soon the pain was searing, molten. I was again and again being dropped on my ass, on marble, from a hundred feet-

I could barely speak enough to tell Hesham to slow down, to stop, to rest my spine. Something was being irrevocably damaged, I was sure. But there was no way to rest. I couldn't get a word out. I struggled for air, I tried to ride higher in the saddle, but couldn't stop because I had to show Hesham I was sturdy, unshrinking. He was glancing back at me periodically and when he did I squinted and smiled in the hardest way I could.

Soon he slowed again. We trotted for a few minutes. The pounding on my spine stopped. The pain subsided. I was so thankful. I took in as much air as I could.

"Yes?" Hesham said.

I nodded.

And he struck my horse again and we galloped.

The pain resumed, with more volume, subtleties, tendrils reaching into new and unknown places - shooting through to my clavicles, armpits, neck. I was intrigued by the newness of the torment and would have studied it, enjoyed it in a way, but its sudden stabbing prevented me from drawing the necessary distance from it.

I needed to prove to this Egyptian lunatic that I could ride with him. That we were equal out here, that I could keep up and devour it, the agony. That I could be punished, that I expected the punishment and could withstand it, however long he wanted to give it to me. We could ride together across the Sahara even though we hated each other for a hundred good and untenable reasons. I was part of a continuum that went back thousands of years, nothing having changed. It almost made me laugh, so I rode as anyone might have ridden at any point in history, meaning that it was only him and me and the sand and a horse and saddle - I had nothing with me at all, was wearing a white button-down shirt and shorts and sandals-and Jesus, however disgusting we were, however wrong was the space between us, we were really soaring.

And I was watching. As the horse's hooves scratched the sand and the horse breathed and I breathed, as the mane whipped over my hands and the sand sprayed over my legs, spitting on my bare ankles, I was watching how the man moved with the horse. Somewhere, after twenty minutes more of continuous pounding, with the horse at full gallop,

I learned. I had been letting the horse strike me, was trying to sit above the saddle, hoping my distance from it would diminish the impact each time, but there were ways to eliminate the pain altogether.

I learned. I moved with the horse and when I finally started moving with that damned horse, nodding forward,...

“These tales reinvigorate that staid old form, the short story, with a jittery sense of adventure.... Eggers does things that should be impossible, and he does them gracefully.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Beautiful stories, anchored in the real world.... How We Are Hungry looks like a classic.”

—The Oregonian

“A tour de force.... These pieces demonstrate the same startling geographic range and sly descriptive acuity that animated You Shall Know Our Velocity.... [Eggers’s] prose is supple, transparent and surprising.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Electrically funny ... full of the raw stuff of lives. The pain and the anger. Emotions that get mixed up and change from one minute to the next. The wonder and the joy. It’s all condensed and crafted, worked, that’s what fiction is. But it feels raw, and it’s exhilarating.”

—The Globe and Mail

“There’s plenty in this collection to remind us that, for all his noodling around, Eggers is phenomenally talented.”

—Washington Post

“[The story ‘Up the Mountain Coming Down Slowly’ is] a masterpiece ... the narration is magisterial, without a false note.... It may well be the last great twentieth-century short story.”

—The Observer (UK)

"'After I Was Thrown in the River and Before I Drowned’ is a small tour de force that ratifies [Eggers’s] ability to write about anything with style and vigour and genuine emotion.”

—The New York Times

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Beautiful stories, anchored in the real world.... How We Are Hungry looks like a classic.”

—The Oregonian

“A tour de force.... These pieces demonstrate the same startling geographic range and sly descriptive acuity that animated You Shall Know Our Velocity.... [Eggers’s] prose is supple, transparent and surprising.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Electrically funny ... full of the raw stuff of lives. The pain and the anger. Emotions that get mixed up and change from one minute to the next. The wonder and the joy. It’s all condensed and crafted, worked, that’s what fiction is. But it feels raw, and it’s exhilarating.”

—The Globe and Mail

“There’s plenty in this collection to remind us that, for all his noodling around, Eggers is phenomenally talented.”

—Washington Post

“[The story ‘Up the Mountain Coming Down Slowly’ is] a masterpiece ... the narration is magisterial, without a false note.... It may well be the last great twentieth-century short story.”

—The Observer (UK)

"'After I Was Thrown in the River and Before I Drowned’ is a small tour de force that ratifies [Eggers’s] ability to write about anything with style and vigour and genuine emotion.”

—The New York Times

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurVintage Canada

- Date d'édition2005

- ISBN 10 0676977804

- ISBN 13 9780676977806

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages224

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 61,52

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

How We Are Hungry: Stories by Dave Eggers

Edité par

Vintage Canada

(2005)

ISBN 10 : 0676977804

ISBN 13 : 9780676977806

Neuf

Paperback

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur Abebooks122027

Acheter neuf

EUR 61,52

Autre devise