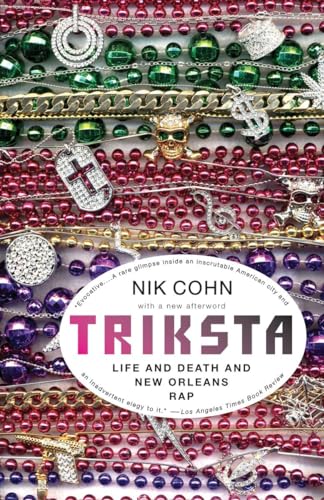

Triksta: Life and Death and New Orleans Rap - Couverture souple

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

I have been obsessed with New Orleans for most of my life; it is the place I’ve loved best on earth. In recent years, however, it has turned violent and distressful, and getting spat on by a child, though mortifying, was hardly headline news. Another time, I’d have muttered a few choice curses and gone on my way. Only, this was not a good moment. I have hepatitis C, a virus that destroys the liver and feels, at least in my case, like permanent jet lag. For the most part, I’ve learned to handle it, but there are days when it handles me. The usual checks and balances cease to function, and I thrash about, untethered, driven by urges I don’t understand and can’t control.

This time I outdid myself. Instead of working out my spleen on some extra pepperoni at Mama Rosa’s, I swung around and walked over to the Iberville project. Not a good idea. I had gone there the first day I ever spent in New Orleans, in 1972, and it had felt welcoming then, but the climate had changed. No outsider, white or black, with a lick of sense would choose to go strolling through the Iberville these days unless they had good reason. In my leather jacket, fat with credit cards, I was asking for trouble. Seeking it out, in fact.

Behind abandoned hulk of Krauss’s department store, I headed into the heart of the project. A few strides brought me to a blind corner. When I turned it, the sunlight was shut out. A few more strides, and a group of youths hemmed me in. None of them spoke or touched me, they simply blocked my path. The brackish smell of bodies was fierce, and I stumbled back against a wall as the youths moved in. Then, just as suddenly as they’d swarmed, they scattered. A city bus had turned the corner and fixed us with its headlamps.

I had never known worse fear. When I regained Basin Street and was safely in a taxi, I was surprised to find I hadn’t pissed or shat myself. That was how it had felt back there—everything running out of me, uncontrollable. And what was most shameful of all, I knew my deepest dread had not been of getting robbed or even shot. I’d been afraid of blackness itself.

Afterward, I tried to blame it on the virus, or the light, or simple aversion to getting mugged. No dice. Over the years, I’d run foul of skinheads in London, neo-Nazis in Brooklyn, sundry policemen around the world. Though never brave, I had managed to keep up some vestige of front. In the Iberville, I was swept by blind animal terror, all pretense at dignity blown.

How could it be? Black music and black culture had been a huge part of my life; so had black friends and lovers. But those, depending on shifting fashion, were negroes or African-Americans. They were nobody’s niggaz.

The same friends and lovers had often told me this: all whites, cut them deep, are racist at core.

I remembered Kerry, a singer I dated some thirty years ago, and how one stoned morning, after we made love, she mocked my record collection, the posters on my walls, all the black artifacts I thought were part of me. Window dressing, she called them, and took my hand and placed it on her breast. This too, she said. She was in my bed, my world; that didn’t mean shit. Drop me off in the ghetto, up against the wall, and see how I felt then. You’d turn cracker in a heartbeat, Kerry said. Of course, I refused to believe her. Other whites, maybe; not me. That poison couldn’t be in me. Yet it was.

My home base is New York, but I visit New Orleans several times a year, often for months at a stretch. Usually, I rent a house, but this was a brief stopover and I was staying in Room 406 at the Villa Convento, a small pension on Ursulines Street, at the back of the French Quarter. My room, strewn with rap CDs that now seemed to mock me, faced onto the street. Deep into the night I lay awake, listening to the tourists trundling past on carriage rides and their guides pointing out the Villa as the site of the House of the Rising Sun, while I went back across my life, sifting through dirt—racial teasing that wasn’t quite teasing, dumb drunken jokes, betrayals big and small. And what I saw in myself, bloated sack of half-truths and jive, was a person I couldn’t live or die with.

I kept replaying those few seconds behind Krauss’s, trying to pin down details. How many youths had there been? Could it be true that none of them spoke? And why in hell was I there, anyway? Who, finally, was I trying to confront? No answers came. All I could conjure up was a rush of amorphous bodies. Seemed like I’d been set upon by people with no faces.

At first light I rose and tried to scour myself in the shower, but the water wouldn’t go past tepid, so I took a walk out of the Quarter through the Faubourg Marigny to the old black neighborhoods of Treme and St. Bernard, once thriving, now impoverished and falling down, heartachingly lovely still.

The streets were almost deserted—just a few homeless men scavenging or pushing shopping carts full of soda cans. At the corner of Pauger and Derbigny, a pickup truck swung by, two laborers on their way to work. A bounce song blasted on their radio; it sounded like Fifth Ward Weebie. I felt the thump of bass in my bones and marrow, and a faint warmth seeped through me. The truck roared off along Pauger, raising yellow dust, and was gone in seconds, but the rumble of bass and Weebie’s rap lingered. I started to walk behind them.

Regular Jugular

Soulja Slim was shot the night before Thanksgiving, 2003.

He was at his mother’s house, the spacious duplex he’d bought her in Gentilly, out toward the lake, in a quiet neighborhood. Slim kept an apartment upstairs, which doubled as his studio.

The day of his death started well. The video for his new single, “Lov Me Lov Me Not,” had arrived from New York. It was his comeback, his big shot at national stardom: “The start of the whole everything,” his mother said later. After he’d got out of jail the last time, Slim had financed an album, Years Later, and put it out on his own label, Cut Throat Committy. It had sold more than thirty thousand copies in New Orleans alone, a phenomenal number for an independent release, and all the more so in this bootleg era, when maybe eighty percent of sales were off the books. Ten thousand was regarded as a hit these days; thirty was ghetto triple-platinum. Now Koch, a major label, had leased the album, added a couple more tracks, renamed it Years Later . . . A Few Months After, and was ready to give it serious promotion. At twenty-six, after thirteen years of rapping and over five years of jail, a heroin addiction and two near-fatal shootings, it looked as if Slim was finally on track.

In the afternoon some of his boyz from Cut Throat came by the house to watch the video. Everyone said it was hot. They planned to go in the studio and cut a new track later on, but first Slim had some errands to run. Around five he took off with his partner Trenity in his Escalade, customized with a flat-screen TV and the razor-slash Cut Throat logo carved into the seats.

By 5:45, when they returned, it was dark. Trenity got out of the passenger seat and went into the house, and Slim followed a few seconds behind. As a rule he stayed armed at all times, but this neighborhood was so peaceable, never a hint of trouble, that he let his guard down. His gun was still in the Escalade as he crossed the lawn and a man stepped to him out of hiding and shot him once in the back, three times in the face. Slim was dead before anyone could reach him.

I heard the news around seven. My phone rang, and a voice I didn’t recognize started talking. Like most Southerners, rappers never bother to identify themselves. “Slim’s gone,” the caller said, then someone started yelling in the background and the line went dead.

A few minutes later, the phone rang again. And it kept ringing all evening. Some of the calls were from people I worked with and knew well, others from virtual strangers. These must have been working through their phone books from A to Z, speed-dialing at random. Though a few seemed surprised to hear a European voice, they plowed on regardless. Slim’s death belonged to everyone.

Nobody seemed shocked. Slim had been running the streets, in harm’s way, from a child, and he was famously confrontational. If anything, the wonder was he’d lasted so long. Even so, there was a sense of awe. A warrior had passed, a great man in his own world. Simply to help spread the news was a form of reflected glory.

It was three years since I had gone walking in the Iberville, two since I started working in rap, and killings had lost their novelty. Normally, when someone got shot, grieving was left to the family. For everyone else, it was more or less business as usual. At Wydell Spotsville’s studio in Pigeon Town, a ravaged area near the Jefferson Parish line, I’d met a kid, fifteen at most. There was an eagerness in his face, a hunger that set him apart. I asked him to rap and he rattled off a verse, freestyling. One rhyme stood out among the standard gangsta posturing: “Need to maximize my worth / ’Fore I leave out this earth.” I asked him to work on that thought and let me hear what came out, but he never showed up again. After a week or so, I asked where he was. “He got popped,” someone said, and Wydell, a godly man, shook his head and sighed. Then he cued another track, and the kid was not mentioned again.

But Slim, that was different. A laundry list of local stars–Pimp Daddy, DJ Irv, Yella Boy, Kilo G, Warren Mays, and many others–had died by violence. Soulja Slim transcended them all. Though he’d never had a national hit, in New Orleans he was a giant. Only Juvenile and Mystikal were in the same league, and neither owned the streets like Slim. Now his legend was complete. Gunned down, he became an immortal–the city’s Tupac, its Biggie Smalls.

In life, his talent had been instinctive and raw. He had the loose-lipped slack mouth, borderline speech impediment, that so many good rappers have, and a natural, low-slung flow, almost conversational. His verses were full of prophetic images, one foot in the Bible, the other in the gutter: “Man I’m in the desert, and surviving is a strong gandle / So I can’t be walking in the wrong sandles, / Feeling like all I got is me myself, and I / Don’t know too many that I can leave my wealth, and die / Empty, ’cos I know that drama will only increase / And who’s gonna carry me, when I’m trapped under them bed sheets?”

His greatest strength was authenticity. The raps were harsh, often vicious, but you knew instinctively that he’d lived every line of them. His was the voice of black New Orleans, in all its ugliness and beauty, its senseless slaughter, its moments of battered grace. He personified the split that lay at the city’s heart–fierce joy in being alive, compulsive embrace of death.

At moments, he seemed to regret the lemming rush to self-destruct: on “Soulja 4 Life,” he spat: “Niggaz today ignorant, specially my little generation / Squeeze triggers with no hesitation for any kind of little altercation.” But doubts were quickly swept aside. A moment later, in what may have been his signature rhyme, he was back to playing the outlaw, one jump ahead of death: “I’ma still ride with my pistol though / An’ drop the top on the low low so I can feel the wind blow . . .”

In another town, he might have worked through his turmoil and come out whole, an agent for change, but New Orleans didn’t want that from him. No rapper had ever moved any records here by pushing messages. The only topics that sold were sex and killing, the more graphic the better. So sex and killing were what Slim served up, with a crazed abandon that none of his rivals could match: “Double-cross me get cha head knocked off bitch / To tha river ya go buck naked wit out no clothes / Bullet lodged in a ya dome, bust open asshole.”

Though we never met, we had many people in common. Among the musicians I worked with, Junie B had rhymed against him at porch contests when they were both coming up in the Magnolia, DJ Chicken and Shorty Brown Hustle had both known him well, Bass Heavy had produced some of his tracks. All, without exception, spoke warmly of him. He was strong medicine, you didn’t mess with him. Rub him the wrong way, and he could be lethal. But he was generous and loyal, a straight shooter in every sense, and when he gave his love, it was absolute. In the rat nest of local rap, full of schemers and backstabbers, he lived by his own notion of honor, and nothing could shake him off it. “To me,” said Junie B, “he was a decent person.”

Myself, I loathed much of what he said but loved the way he said it. This night of his death, I sat listening to The Streets Made Me, his most cohesive album, and studied his face on the CD cover–thick-lipped and gold-toothed, with a blurry jailhouse tattoo of a crucifix between his eyes, a humorous twist to his mouth, and a wild spirit, at once ugly and beautiful.

From the Hardcover edition.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurVintage

- Date d'édition2007

- ISBN 10 1400077060

- ISBN 13 9781400077069

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages256

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,68

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Triksta: Life and Death and New Orleans Rap

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_1400077060

Triksta: Life and Death and New Orleans Rap

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Brand New Copy. N° de réf. du vendeur BBB_new1400077060

Triksta: Life and Death and New Orleans Rap

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think1400077060

Triksta: Life and Death and New Orleans Rap

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover1400077060

Triksta: Life and Death and New Orleans Rap

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard1400077060

TRIKSTA: LIFE AND DEATH AND NEW

Description du livre Etat : New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.55. N° de réf. du vendeur Q-1400077060