Articles liés à The Tiger's Wife

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

The Coast

the forty days of the soul begin on the morning after death. That first night, before its forty days begin, the soul lies still against sweated-on pillows and watches the living fold the hands and close the eyes, choke the room with smoke and silence to keep the new soul from the doors and the windows and the cracks in the floor so that it does not run out of the house like a river. The living know that, at daybreak, the soul will leave them and make its way to the places of its past—the schools and dormitories of its youth, army barracks and tenements, houses razed to the ground and rebuilt, places that recall love and guilt, difficulties and unbridled happiness, optimism and ecstasy, memories of grace meaningless to anyone else—and sometimes this journey will carry it so far for so long that it will forget to come back. For this reason, the living bring their own rituals to a standstill: to welcome the newly loosed spirit, the living will not clean, will not wash or tidy, will not remove the soul’s belongings for forty days, hoping that sentiment and longing will bring it home again, encourage it to return with a message, with a sign, or with forgiveness.

If it is properly enticed, the soul will return as the days go by, to rummage through drawers, peer inside cupboards, seek the tactile comfort of its living identity by reassessing the dish rack and the doorbell and the telephone, reminding itself of functionality, all the time touching things that produce sound and make its presence known to the inhabitants of the house.

Speaking quietly into the phone, my grandma reminded me of this after she told me of my grandfather’s death. For her, the forty days were fact and common sense, knowledge left over from burying two parents and an older sister, assorted cousins and strangers from her hometown, a formula she had recited to comfort my grandfather whenever he lost a patient in whom he was particularly invested—a superstition, according to him, but something in which he had indulged her with less and less protest as old age had hardened her beliefs.

My grandma was shocked, angry because we had been robbed of my grandfather’s forty days, reduced now to thirty-seven or thirty-eight by the circumstances of his death. He had died alone, on a trip away from home; she hadn’t known that he was already dead when she ironed his clothes the day before, or washed the dishes that morning, and she couldn’t account for the spiritual consequences of her ignorance. He had died in a clinic in an obscure town called Zdrevkov on the other side of the border; no one my grandma had spoken to knew where Zdrevkov was, and when she asked me, I told her the truth: I had no idea what he had been doing there.

“You’re lying,” she said.

“Bako, I’m not.”

“He told us he was on his way to meet you.”

“That can’t be right,” I said.

He had lied to her, I realized, and lied to me. He had taken advantage of my own cross-country trip to slip away—a week ago, she was saying, by bus, right after I had set out myself—and had gone off for some reason unknown to either of us. It had taken the Zdrevkov clinic staff three whole days to track my grandma down after he died, to tell her and my mother that he was dead, arrange to send his body. It had arrived at the City morgue that morning, but by then, I was already four hundred miles from home, standing in the public bathroom at the last service station before the border, the pay phone against my ear, my pant legs rolled up, sandals in hand, bare feet slipping on the green tiles under the broken sink.

Somebody had fastened a bent hose onto the faucet, and it hung, nozzle down, from the boiler pipes, coughing thin streams of water onto the floor. It must have been going for hours: water was everywhere, flooding the tile grooves and pooling around the rims of the squat toilets, dripping over the doorstep and into the dried-up garden behind the shack. None of this fazed the bathroom attendant, a middle-aged woman with an orange scarf tied around her hair, whom I had found dozing in a corner chair and dismissed from the room with a handful of bills, afraid of what those seven missed beeper pages from my grandma meant before I even picked up the receiver.

I was furious with her for not having told me that my grandfather had left home. He had told her and my mother that he was worried about my goodwill mission, about the inoculations at the Brejevina orphanage, and that he was coming down to help. But I couldn’t berate my grandma without giving myself away, because she would have told me if she had known about his illness, which my grandfather and I had hidden from her. So I let her talk, and said nothing about how I had been with him at the Military Academy of Medicine three months before when he had found out, or how the oncologist, a lifelong colleague of my grandfather’s, had shown him the scans and my grandfather had put his hat down on his knee and said, “Fuck. You go looking for a gnat and you find a donkey.”

I put two more coins into the slot, and the phone whirred. Sparrows were diving from the brick ledges of the bathroom walls, dropping into the puddles at my feet, shivering water over their backs. The sun outside had baked the early afternoon into stillness, and the hot, wet air stood in the room with me, shining in the doorway that led out to the road, where the cars at border control were packed in a tight line along the glazed tarmac. I could see our car, left side dented from a recent run-in with a tractor, and Zóra sitting in the driver’s seat, door propped open, one long leg dragging along the ground, glances darting back toward the bathroom more and more often as she drew closer to the customs booth.

“They called last night,” my grandma was saying, her voice louder. “And I thought, they’ve made a mistake. I didn’t want to call you until we were sure, to worry you in case it wasn’t him. But your mother went down to the morgue this morning.” She was quiet, and then: “I don’t understand, I don’t understand any of it.”

“I don’t either, Bako,” I said.

“He was going to meet you.”

“I didn’t know about it.”

Then the tone of her voice changed. She was suspicious, my grandma, of why I wasn’t crying, why I wasn’t hysterical. For the first ten minutes of our conversation, she had probably allowed herself to believe that my calm was the result of my being in a foreign hospital, on assignment, surrounded, perhaps, by colleagues. She would have challenged me a lot sooner if she had known that I was hiding in the border-stop bathroom so that Zóra wouldn’t overhear.

She said, “Haven’t you got anything to say?”

“I just don’t know, Bako. Why would he lie about coming to see me?”

“You haven’t asked if it was an accident,” she said. “Why haven’t you asked that? Why haven’t you asked how he died?”

“I didn’t even know he had left home,” I said. “I didn’t know any of this was going on.”

“You’re not crying,” she said.

“Neither are you.”

“Your mother is heartbroken,” she said to me. “He must have known. They said he was very ill—so he must have known, he must have told someone. Was it you?”

“If he had known, he wouldn’t have gone anywhere,” I said, with what I hoped was conviction. “He would have known better.” There were white towels stacked neatly on a metal shelf above the mirror, and I wiped my face and neck with one, and then another, and the skin of my face and neck left gray smears on towel after towel until I had used up five. There was no laundry basket to put them in, so I left them in the sink. “Where is this place where they found him?” I said. “How far did he go?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “They didn’t tell us. Somewhere on the other side.”

“Maybe it was a specialty clinic,” I said.

“He was on his way to see you.”

“Did he leave a letter?”

He hadn’t. My mother and grandma, I realized, had both probably seen his departure as part of his unwillingness to retire, like his relationship with a new housebound patient outside the City—a patient we had made up as a cover for his visits to the oncologist friend from the weekly doctors’ luncheon, a man who gave injections of some formulas that were supposed to help with the pain. Colorful formulas, my grandfather said when he came home, as if he knew the whole time that the formulas were just water laced with food coloring, as if it didn’t matter anymore. He had, at first, more or less retained his healthy cast, which made hiding his illness easier; but after seeing him come out of these sessions just once, I had threatened to tell my mother, and he said: “Don’t you dare.” And that was that.

My grandma was asking me: “Are you already in Brejevina?”

“We’re at the border,” I said. “We just came over on the ferry.”

Outside, the line of cars was beginning to move again. I saw Zóra put her cigarette out on the ground, pull her leg back in and slam the door. A flurry of people who had assembled on the gravel shoulder to stretch and smoke, to check their tires and fill water bottles at the fountain, to look impatiently down the line, or dispose of pastries and sandwiches they had been attempting to smuggle, or urinate against the side of the bathroom, scrambled to get back to their vehicles.

My grandma was silent for a few moments. I could hear the line clicking, and then she said: “Your mother wants to have the funeral in the next few days. Couldn’t Zóra go on to Brejevina by herself?”

If I had told Zóra about it, she would have made me go home immediately. She would have given me the car, taken the vaccine coolers, and hitchhiked across the border to make the University’s good-faith delivery to the orphanage at Brejevina up the coast. But I said: “We’re almost there, Bako, and a lot of kids are waiting on these shots.”

She didn’t ask me again. My grandma just gave me the date of the funeral, the time, the place, even though I already knew where it would be, up on Strmina, the hill overlooking the City, where Mother Vera, my great-great-grandmother, was buried. After she hung up, I ran the faucet with my elbow and filled the water bottles I had brought as my pretext for getting out of the car. On the gravel outside, I rinsed off my feet before putting my shoes back on; Zóra left the engine running and jumped out to take her turn while I climbed into the driver’s seat, pulled it forward to compensate for my height, and made sure our licenses and medication import documents were lined up in the correct order on the dashboard. Two cars in front of us, a customs official, green shirt clinging to his chest, was opening the hatchback of an elderly couple’s car, leaning carefully into it, unzipping suitcases with a gloved hand.

When Zóra got back, I didn’t tell her anything about my grandfather. It had already been a bleak year for us both. I had made the mistake of walking out with the nurses during the strike in January; rewarded for my efforts with an indefinite suspension from the Vojvodja clinic, I had been housebound for months—a blessing, in a way, because it meant I was around for my grandfather when the diagnosis came in. He was glad of it at first, but never passed up the opportunity to call me a gullible jackass for getting suspended. And then, as his illness wore on, he began spending less and less time at home, and suggested I do the same; he didn’t want me hanging around, looking morose, scaring the hell out of him when he woke up without his glasses on to find me hovering over his bed in the middle of the night. My behavior, he said, was tipping my grandma off about his illness, making her suspicious of our silences and exchanges, and of the fact that my grandfather and I were busier than ever now that we were respectively retired and suspended. He wanted me to think about my specialization, too, about what I would do with myself once the suspension was lifted—he was not surprised that Srdjan, a professor of biochemical engineering with whom I had, according to my grandfather, “been tangling,” had failed to put in a good word for me with the suspension committee. At my grandfather’s suggestion, I had gone back to volunteering with the University’s United Clinics program, something I hadn’t done since the end of the war.

Zóra was using this volunteering mission as an excuse to get away from a blowup at the Military Academy of Medicine. Four years after getting her medical degree, she was still at the trauma center, hoping that exposure to a variety of surgical procedures would help her decide on a specialization. Unfortunately, she had spent the bulk of that time under a trauma director known throughout the City as Ironglove—a name he had earned during his days as chief of obstetrics, when he had failed to remove the silver bracelets he kept stacked on his wrist during pelvic examinations. Zóra was a woman of principle, an open atheist. At the age of thirteen, a priest had told her that animals had no souls, and she had said, “Well then, fuck you, Pops,” and walked out of church; four years of butting heads with Ironglove had culminated in an incident that Zóra, under the direction of the state prosecutor, was prohibited from discussing. Zóra’s silence on the subject extended even to me, but the scraps I had heard around hospital hallways centered around a railway worker, an accident, and a digital amputation during which Ironglove, who may or may not have been inebriated, had said something like: “Don’t worry, sir—it’s a lot easier to watch the second finger come off if you’re biting down on the first.”

Naturally, a lawsuit was in the works, and Zóra had been summoned back to testify against Ironglove. Despite his reputation, he was still well connected in the medical community, and now Zóra was torn between sticking it to a man she had despised for years, and risking a career and reputation she was just beginning to build for herself; for the first time no one—not me, not her father, not her latest boyfriend—could point her in the right direction. After setting out, we had spent a week at the United Clinics headquarters for our briefing and training, and all this time she had met both my curiosity and the state prosecutor’s incessant phone calls with the same determined silence. Then yesterday, against all odds, she had admitted to wanting my grandfather’s advice as soon as we got back to the City. She hadn’t seen him around the hospital for the past month, hadn’t seen his graying face, the way his skin was starting to loosen around his bones.

We watched the customs officer confiscate two jars of beach pebbles from the elderly couple, and wave the next car through; when he got to us, he spent twenty minutes looking over our passports and identity cards, our letters of certification from the University. He opened the medicine coolers and lined them up on the tarmac while Zóra towered over him, arms crossed, and then said, “You realize, of course, that the fact that it’s in a cooler means it’s temperature-sensitive—or don’t they teach you about refrigeration at the village schoolhouse?” knowing that everything was in order, knowing that, realistically, he couldn’t touch us. This challenge, however, prompted him to search the car for weapons, stowaways, shellfish, and uncertified pets for a further thirty minutes.

Twelve years ago, before the war, the people of Brejevina had been our people. The border had been a joke, an occasional formality, and you used to drive or fly or walk across as you pleased, by woodland, by water, by open plain. You used to offer the customs officials sandwiches or jars of pickled peppers as you went through. Nobody asked you your name—although, as it turned out, everyone had apparently been anxious about it all along...

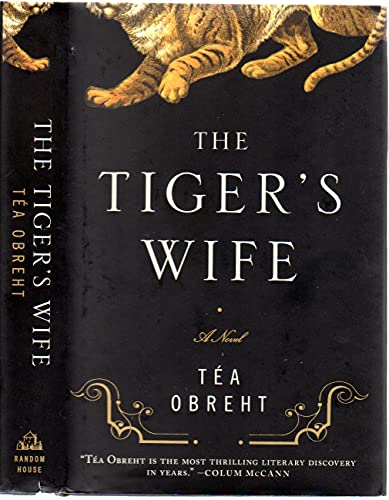

NATIONAL BOOK AWARD FINALIST • NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY The Wall Street Journal • O: The Oprah Magazine • The Economist • Vogue • Slate • Chicago Tribune • The Seattle Times • Dayton Daily News • Publishers Weekly • Alan Cheuse, NPR’s All Things Considered

SELECTED ONE OF THE TOP 10 BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times • Entertainment Weekly • The Christian Science Monitor • The Kansas City Star • Library Journal

In a Balkan country mending from war, Natalia, a young doctor, is compelled to unravel the mysterious circumstances surrounding her beloved grandfather’s recent death. Searching for clues, she turns to his worn copy of The Jungle Book and the stories he told her of his encounters over the years with “the deathless man.” But most extraordinary of all is the story her grandfather never told her—the legend of the tiger’s wife.

Look for special features inside. Join the Circle for author chats and more.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurWeidenfeld & Nicolson

- Date d'édition2011

- ISBN 10 0297859013

- ISBN 13 9780297859017

- ReliureRelié

- Numéro d'édition1

- Nombre de pages352

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 24

De Irlande vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

the Tiger's Wife

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Etat de la jaquette : New. 1st Edition. First UK Edition, First Printing. This is a true first edition, first printing (first impression) with a full numberline beginning with [1] to the copyright page to indicate a true first print in a Very Fine Dust Jacket. SIGNED and dated by the author to the title page. [ Tea Obreht 04.09.2013 ]. Signed by Author(s). N° de réf. du vendeur 014903

The Tiger's Wife - Signed & Dated Uk 1st Ed. 1st Print HB. Winner of the 2011 Orange Prize for Fiction.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. 1st Edition. A new signed UK 1st Edition 1st Printing Hardback. Signed & dated by the author to the title page. Free from inscriptions. Fine & unread. No pushing to spines. No knocks to corners. Dust Jacket fine, (not price clipped), now covered in removable clear protective film. Winner of the 2011 Orange Prize for Fiction. All books sold by me are posted well packed with bubble wrap inside a cardboard book box. Prompt dispatch within 2-3 days. Photographs available upon request. Any questions please contact me. Signed by Author(s). N° de réf. du vendeur ABE-1709724614135

The Tiger's Wife

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Etat de la jaquette : New. First Edition. A fine unread 1st impression in a fine dustwrapper, Signed and dated (30.05.2011) by the Author on the title page. Signed at the Hay Festival. Signed by Author(s). N° de réf. du vendeur 008897

THE TIGER'S WIFE Signed, Located & Dated

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Etat de la jaquette : New. 1st Edition. Scarce first edition, first printing of what is being described as 'the most thrilling literary discovery in years.' Full numberline 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2. Signed, located 'Bath' and dated 31.05.2011 to the title page by Tea Obreht at a recent event in Bath. A fine unread hardcover in a like dustwrapper.SHIPPED IN A BOX WITH PLENTY OF ADDED PROTECTION. Signed by Author(s). N° de réf. du vendeur 476328

The Tiger's Wife 1st 1st New Signed Located & Dated

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Etat de la jaquette : New. 1st Edition. Tea Obreht The Tiger's Wife 1st 1st New Signed Located & Dated will be sent boxed and via a signed for method of postage Extra postage will be needed for overseas orders if the weight exceeds one kilo book is signed without dedication unless stated otherwise. All books come with a lifetime guarantee No Coa's issued unless the book originally came with one then it will be included with the book. Signed by Author. N° de réf. du vendeur ABE-1563358921504