Articles liés à Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best...

Synopsis

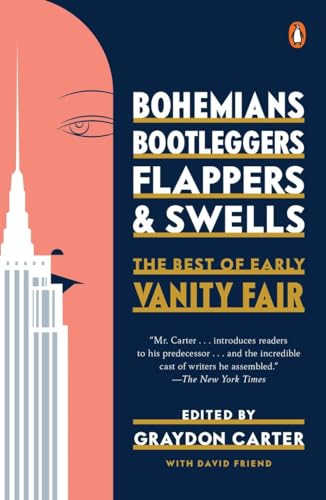

Offering readers an inebriating swig from the great cocktail shaker of the Roaring Twenties—the Jazz Age, the age of Gatsby—Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells showcases unforgettable writers in search of how to live well in a changing era. Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter introduces these fabulous pieces written between 1913 and 1936, when the magazine published a Murderers’ Row of the world’s leading literary lights, including:

- F. Scott Fitzgerald on what a magazine should be

- Clarence Darrow on equality

- e. e. cummings on Calvin Coolidge

- D. H. Lawrence on women

- Djuna Barnes on James Joyce

- John Maynard Keynes on the collapse in money value

- Dorothy Parker on a host of topics, from why she hates actresses to why she hasn’t married

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

À propos de l?auteur

Graydon Carter has been the editor of Vanity Fair since 1992. He lives in New York City.

David Friend is Vanity Fair’s editor of creative development.

Extrait. © Reproduit sur autorisation. Tous droits réservés.

VANITY FAIR AND THE BIRTH OF THE NEW

GRAYDON CARTER

When the dreariness, the madness, and, oh, the sheer tackiness of modern life get to you, isn’t it tempting to imagine a different life in a different place and period? The places and periods I go to in my mind—and I have no rational explanation for this—are invariably set in big cities in the last century: San Francisco in the sixties, Paris in the fifties, London between the wars, Los Angeles in the thirties. And for the purposes of this introduction: the New York of the twenties. New York back in those days was the fizzy incubator of the Jazz Age and the Roaring Twenties. It was the big room: Jimmy Walker was mayor; Wall Street and bootlegging were booming; jazz, modern art, and talkies were the rage; everyone—from statesmen to sandhogs—was trying to get their head around the latest theories of Freud and Einstein; and the bible for the smart set was Vanity Fair.

It was the modern magazine during that early incarnation, from 1913 to 1936. And everybody, but everybody, wrote for it, including, in no particular order, P. G. Wodehouse, Alexander Woollcott, F. Scott Fitzgerald, T. S. Eliot, e. e. cummings, Noël Coward, Gertrude Stein, A. A. Milne, Stephen Leacock, Thomas Mann, Djuna Barnes, Bertrand Russell, Aldous Huxley, Langston Hughes, Sherwood Anderson, Walter Lippmann, Carl Sandburg, Theodore Dreiser, Colette, John Maynard Keynes, Ford Madox Ford, Clarence Darrow, Janet Flanner, Paul Gallico, Dalton Trumbo, William Saroyan, Thomas Wolfe, Walter Winchell, and Douglas Fairbanks (both Sr. and Jr.).

They were drawn to Vanity Fair by a decent word rate and by the magazine’s editor, Frank Crowninshield. He was known as Crownie to his intimates, who recognized him for his skills as a cultural clairvoyant and a taste maker. He helped launch the seminal Armory Show in 1913, which introduced avant-garde painting to America, and was a founding trustee of the Museum of Modern Art. He would also play a significant role in the birth of what came to be known as café society, cohosting small get-togethers with Condé Nast, the publisher of Vanity Fair and Vogue. Their parties brought together the era’s brightest minds, talents, and wits, and were staged at the thirty-room penthouse apartment at 1040 Park Avenue that Crowninshield and Nast shared. (Same-sex domesticity was not uncommon back then.)

• • •

For twenty-two roller-coaster years, Crowninshield reveled in his singular cultural perch atop the masthead of what became the quintessential Jazz Age magazine. His Vanity Fair brimmed with groundbreaking photography and bold illustration and design. But just as important—in ample evidence here—were its sparkling essays, commentary, profiles, poetry, and fiction from many of the most forward-thinking writers of the day. Some contributors were public intellectuals (Huxley, Russell, H. L. Mencken). Others were experts in what was then experimental art and music (Clive Bell, Roger Fry, Gertrude Stein, George Jean Nathan, Virgil Thompson, Tristan Tzara, Carl Van Vechten). Still others, such as Fitzgerald, Anita Loos, John Emerson, and Donald Ogden Stewart, would go west to seek their fortune in the movie trade.

The offices of the magazine in those days—first on fabled West Forty-fourth Street and later in the new Graybar Building, adjacent to Grand Central Terminal—reflected its editor’s eclectic tastes. Crowninshield, who had a soft spot for sleight of hand, kept a deck of cards ready for the amusement of staffers or for guests who would often pop in—Harry Houdini, say, or Charlie Chaplin. Editorial lunches with his three rising staff members, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, and Robert Sherwood, consisted of eggs Benedict, kippered herring, chocolate éclairs, and café spécial.

According to Condé Nast’s biographer Caroline Seebohm, Crownie would run the office “with the greatest informality. Actresses, models, photographers, and writers were always milling about in the reception room, under the impression that he had invited them to a personal interview. (He often had.)” On many Saturday nights, Crowninshield could be found gambling in the basement of a brownstone on East Thirty-seventh Street, where friends like Woollcott would place wagers on tiny mechanical horses that would zip around a tabletop racetrack, the random victor determined by what they called a “chance machine.”

• • •

Crowninshield both sought and attracted excellence. The senior editors who would pass through Vanity Fair’s doors were a storied lot: not only Parker, Benchley, and Sherwood, but also Edmund Wilson, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Clare Boothe Brokaw, a brash, young dynamo who would eventually sleep her way through much of the masthead. (She also wrote the play The Women, married Henry Luce, and became a congresswoman and a U.S. ambassador to Italy.)

The magazine regularly predicted which cultural forces would leave a lasting mark. (To that end, I recommend the stories in this volume on Picasso, Chaplin, James Joyce, W. Somerset Maugham, Joan Crawford, Cole Porter, and Babe Ruth.) They took the pulse of the period—in real time—with an unrivaled sense of taste. The writing in Vanity Fair pushed boundaries with its muscular and often experimental prose. In examining the daunting shape of things to come, the magazine’s writers wrote about men’s rites and women’s rights, the intrusive media and exclusive bastions of the well-to-do. They questioned our destructive fascination with the entertainment industry and our addiction to organized sports. They used satire to criticize ostentation, Prohibition, marital duplicity, and the grinding new “publicity machine.” Social historian Cleveland Amory would later observe that the magazine was “as accurate a social barometer of its time as exists.” The finest pieces in the Jazz Age Vanity Fair, seventy-two of which are collected here, focus more often than not on how Americans, especially New Yorkers, in confronting the Machine Age, radical art, urbanization, Communism, Fascism, globalization (epitomized by a World War), and the battle of the sexes, were coping with the growing pains of a new phenomenon: modern life.

1910s

THE PHYSICAL CULTURE PERIL

P. G. WODEHOUSE

FROM MAY 1914

Physical culture is in the air just now. Where, a few years ago, the average man sprang from bed to bath and from bath to breakfast-table, he now postpones his onslaught on the boiled egg for a matter of fifteen minutes. These fifteen minutes he devotes to a series of bendings and stretchings which in the course of time are guaranteed to turn him into a demi-god. The advertisement pages of the magazines are congested with portraits of stern-looking, semi-nude individuals with bulging muscles and fifty-inch chests, who urge the reader to write to them for an illustrated booklet. Weedy persons, hitherto in the Chippendale class, are developing all sort of unsuspected thews, and the moderately muscular citizen (provided he has written for and obtained the small illustrated booklet) begins to have grave doubts as to whether he will be able, if he goes on at this rate, to get the sleeves of his overcoat over his biceps.

To the superficial thinker this is all very splendid. The vapid and irreflective observer looks with approval on the growing band of village blacksmiths in our midst. But you and I, reader, shake our heads. We are uneasy. We go deeper into the matter, and we are not happy in our minds. We realize that all this physical improvement must have its effect on the soul.

• • •

A man who does anything regularly is practically certain to become a bore. Man is by nature so irregular that, if he takes a cold bath every day or keeps a diary every day or does physical exercises every day, he is sure to be too proud of himself to keep quiet about it. He cannot help gloating over the weaker vessels who turn on the hot tap, forget to enter anything after January the fifth, and shirk the matutinal development of their sinews. He will drag the subject into any conversation in which he happens to be engaged. And especially is this so as regards physical culture.

The monotony of doing these exercises every morning is so appalling that it is practically an impossibility not to boast of having gone through with them. Many a man who has been completely reticent on the topic of his business successes and his social achievements has become a mere babbler after completing a month of physical culture without missing a day. It is the same spirit which led Vikings in the old days to burst into song when they had succeeded in cleaving some tough foeman to the chine.

• • •

Again, it is alleged by scientists that it is impossible for the physical culturist to keep himself from becoming hearty, especially at breakfast, in other words a pest. Take my own case. Once upon a time I was the most delightful person you ever met. I would totter in to breakfast of a morning with dull eyes, and sink wearily into a chair. There I would remain, silent and consequently inoffensive, the model breakfaster. No lively conversation from me. No quips. No cranks. No speeches beginning “I see by the paper that . . .” Nothing but silence, a soggy, soothing silence. If I wanted anything, I pointed. If spoken to, I grunted. You had to look at me to be sure that I was there. Those were the days when my nickname in the home was Little Sunshine.

Then one day some officious friend, who would not leave well alone, suggested that I should start those exercises which you see advertised everywhere. I weakly consented. I wrote for the small illustrated booklet. And now I am a different man. Little by little I have become just like that offensive young man you see in the advertisements of the give-you-new-life kind of medicines—the young man who stands by the bedside of his sleepy friend, and says, “What! Still in bed, old man! Why, I have been out with the hounds a good two hours. Nothing tires me since I tried Peabody and Finklestein’s Liquid Radium.” At breakfast I am hearty and talkative. Throughout the day I breeze about with my chest expanded, a nuisance to all whom I encounter. I slap backs. My handshake is like the bite of a horse.

• • •

Naturally, this has lost me a great many friends. But far worse has been the effect on my moral fiber. Before, I was modest. Now, I despise practically everybody except professional pugilists. I meet some great philosopher, and, instead of looking with reverence at his nobby forehead, I merely feel that, if he tried to touch his toes thirty times without bending his knees, he would be in the hospital for a week. An eminent divine is to me simply a man who would have a pretty thin time if he tried to lie on his back and wave his legs fifteen times in the air without stopping. . . .

There is another danger. I heard, or read, somewhere of a mild and inoffensive man to whom Nature, in her blind way, had given a wonderful right-hand punch. Whenever he got into an argument, he could not help feeling that there the punch was and it would be a pity to waste it. The knowledge that he possessed that superb hay-maker was a perpetual menace to him. He went through life a haunted man. Am I to become like him? Already, after doing these exercises for a few weeks, I have a waist-line of the consistency of fairly stale bread. In time it must infallibly become like iron. There is a rudimentary muscle growing behind my right shoulder-blade. It looks like an orange and is getting larger every day. About this time next year, I shall be a sort of human bomb. I will do my very best to control myself, but suppose a momentary irritation gets the better of me and I let myself go! It does not bear thinking of.

• • •

Brooding tensely over this state of things, I have, I think, hit on a remedy. What is required is a system of spiritual exercises which shall methodically develop the soul so that it keeps pace with the muscles and the self-esteem.

Let us say that you open with that exercise where you put your feet under the chest of drawers and sit up suddenly. Well, under my new system, instead of thinking of the effect of this maneuver on the abdominal muscles, you concentrate your mind on some such formula as, “I must remember that I have not yet subscribed to the model farm for tuberculous cows.”

Having completed this exercise, you stand erect and swing the arms from left to right and from right to left without moving the lower half of the body. As you do this, say to yourself, “This, I know, is where I get the steel-and-indiarubber results on my deltoids, but I must not forget that there are hundreds of men whose confining work in the sweat shops has entirely deprived them of opportunities to contract eugenic marriages.”

This treatment, you will find, induces a humble frame of mind admirably calculated to counterbalance the sinful pride engendered by your physical exercises.

Space forbids a complete list of these spiritual culture exercises, but I am now preparing a small illustrated booklet, particulars of which will be found in the advertising pages. An accompanying portrait shows me standing with my hands behind my head and with large, vulgar muscles standing out all over me. But there is a vast difference, which you will discover when you look at my face. I am not wearing the offensively preoccupied expression of most physical-culture advertisements. You will notice a rapt, seraphic expression in the eyes and a soft and spiritual suggestion of humility about the mouth.

AUGUST STRINDBERG

GEORG BRANDES

FROM OCTOBER 1914

Strindberg was the most brilliant author of modern Sweden, and one of the most gifted I have ever known. Ibsen, in speaking of him, once said: “Here is a greater man than I.”

But Strindberg was a wholly abnormal type, mentally. A man so eccentric that, except for his masterly writings, I should have called him insane.

But let me begin by saying a word as to his physical appearance! His strongly modeled forehead clashed strangely with the vulgarity of his lower features. The forehead reminded one of Jupiter’s; the mouth and chin of a Stockholm street urchin. He looked as though he sprang from irreconcilable races. The upper part of his face was that of the mental aristocrat,—the lower belonged to “the servant girl’s son,” as he called himself in his autobiography.

During a long acquaintance with him I was fortunate in being able to agree with him on fundamental principles and to find that minor differences of opinion never irritated him against me, nor caused the slightest break between us.

It was my fate to be present at many crucial moments in Strindberg’s mental life. More than once I have seen him on the turn-rail, as it were, which changed the entire direction of his spiritual and mental locomotive. And each time I have been able to remark how deep and sincere were his changes, even if they contained a trace of the theatrical in their outward expressions.

• • •

I saw Strindberg for the first time during a short stay which he made in Denmark. I remember his first visit to me very clearly, because he made several rather odd remarks to me. After the usual greetings had been exchanged I asked him if he had any friends or relatives in the little town of Roskilde, for I had seen by the papers that he had spent a good deal of time there.

“Indeed not,” he replied. “I visited Roskilde on account of the Bistrup Insane Asylum, which, as you know, is located there. I wanted the director to give me a certificate as to my sanity. I have an idea my relatives are plotting to trap me.”

“And what did the doctor say?” I asked.

“He said he could not give me a certificate off hand, but that he undoubtedly could do so if I would remain there under observation for a few weeks.”

I then realized that I was dealing with an original temperament. Strindberg continued:

“I suppose you know that my tragic and ridiculous marriage has been broken off?”

“I did not even know you were married,” I replied. “I am thoroughly familiar with your books, but I know nothing whatever of your private life.”

Let me explain that Strindberg’s hatred of women amounted almost to a monomania. Many critics have attributed his violent antipathy to them—an obsession which colored all of his work—to his first marriage, which, as is well known, was most unhappy. But, like many women haters—Schopenhauer, merely to quote an example—Strindberg was always under some strong feminine influence.

At about this time he asked me to direct the rehearsals of his play “The Father” at the Casino Theatre in Copenhagen. A few days later, as I was trying to explain the play to the actors, who were used to plays dealing with more frivolous subjects, Strindberg tapped me on the shoulder and said:

“Listen! Is 1500 kr. too much to pay here for an apartment of six rooms and a kitchen?”

“But why in the world do you want six rooms, you, a single man!”

“I am not single! I have a wife and three children with me.”

“You must excuse me, but did you not say the other day that your marriage had been broken off?”

“In a measure, yes! I sent Madame Strindberg away as my wife, but I have retained her as my mistress.”

“Excuse me, but such a thing is impossible. By all the laws of this country under such circumstances, she immediately becomes your wife again. You may safely embark on such a venture with any other woman in the world but not with your wife.”

• • •

One November night in the year 1896, I witnessed a crisis in Strindberg’s life. I had been out, and found his card on my desk as I returned. He was passing through Copenhagen, he had written, and did not wish to leave the city without seeing me. And he asked me to meet him in some quiet place, as he had brought no good clothes with him.

From this note I gathered that he must have grown more peculiar than ever. When I reached his hotel I learned that he had already gone to bed.

“He sent for me himself,” I said.

The door of his room was open. He was in bed, fast asleep. As I touched him on the shoulder he awoke and said:

“I took a sleeping powder. I felt sure you wouldn’t come.”

But he got up and dressed himself quickly, and it turned out that he was much better dressed than I. While dressing, he said:

“Did you know that my existence was predicted, long ago, by Balzac?”

“Where?”

“In ‘Seraphitus-Seraphita.’” He searched for the book in his valise, opened it and pointed to the words: ‘Once again the light shall come the North.’ “There! you see, Balzac refers to me.”

I said, to tease him a little: “How do you know Balzac didn’t allude to Ibsen?”

“Oh, no, he meant me, there isn’t a doubt about it.”

Balzac’s book had made a strong impression on him on account of its touches of Swedenborgianism.

We went to a restaurant and ordered some wine. Strindberg grew excited as he talked.

“You’re out of touch with the reigning intellectual movements,” he said. “We’re living in an age of occultism. Occultists rule the life and literature of our day. Everything else is out of date.”

• • •

He spoke with much admiration of the newer occultists and with real reverence of Joseph Pelladan who, at the time, still called himself Sar and Mage. He also spoke of the Marquis of Guita, about whom his friend Maurice Barres had written a book. I told him that I had been following with interest the discussion between Huysmans and Guita. Huysmans—then living in Lyons—accused Guita—residing in Paris—of having willed him acute pains in the chest by means of black magic. Guita retorted that he dealt with white magic only, not black, and described his proceedings. To this Huysmans replied that he had seen the ingredients of black magic in a closet in Guita’s home.

This remark excited Strindberg violently. “Is it possible,” he asked, “that Huysmans had the same experience as I? I’ve been suffering, too, from a pain in the chest which a man in Stockholm caused me during my stay in Paris.”

“Who was he?”

“My one time benefactor, who tried to punish me for my recent ingratitude.”

Then, without transition: “You have an enemy. A newspaper enemy. I want to do something for you. Let me kill your enemy.”

“You’re very kind. But I should prefer not.”

“But no one would know about it.”

“So all criminals think. Besides, don’t you feel it would be rather unjust to kill a man on account of an unkind newspaper article?”

“Well, let’s not kill him. We’ll simply blind him.”

“I still have my doubts. However, how would you go about it?”

“If you will give me the man’s photograph, I will, with my magic, blind him by driving a needle through his eyes.”

“In that case, you could easily deprive me of my eyesight, too, if you wished?”

“Hardly. It must be done with hatred.”

“Granted, but if a man who hates me tears my picture into pieces, will I fall to the ground in bleeding bits?”

This remark seemed to put him out, and he did not answer me.

He continued, however, to explain in detail the intricacies of magic—black and white—and he dwelt particularly on the evils of black magic when exercised by criminal hands.

The restaurant closed, and we began to walk up and down along the water-front.

• • •

At one time Strindberg was greatly interested in alchemy. He even claimed to have obtained gold in small quantities.

He once gave me a copy of his book, “Inferno.” All through it there runs the mortal fear of persecution. The book shows that he felt that a special interest attached to his every movement, and that supernatural powers were forever busied with him, now warning him, now punishing him, now guiding him and never allowing him to get out of their reach. In Paris, for instance, he felt this distinctly. Strindberg lived in constant fear of being murdered by a Polish writer for having loved the latter’s wife before she met her husband. A Norwegian artist—a friend of the Pole—met Strindberg, and, probably in order to play a joke on him, told him that the dreaded man was expected in Paris.

“Is he coming to kill me?” asked Strindberg.

“Of course. Be on your guard.”

Strindberg wished, however, more details, and decided to look the artist up, but he dared not approach the house. A few days later he screwed up his courage and went to call on him. At the door he saw a little girl on the doorstep. In her hand she held a playing card. It was the ten of spades.

“The ten of spades,” he shouted. “There is foul play in this house,” he muttered, and hastily left the place.

In “Inferno” Strindberg thought that he had finally found the explanation of many of the mysteries of Swedenborg’s spirit world. The book closes with Strindberg’s longing to seek solace in the Catholic Church. Swedenborg had prejudiced him against Protestantism, explaining that it was treason against the Mother Church. The growth of the Catholic Church in America, England and Scandinavia seemed to him to prove the decisive triumph of Catholicism over Protestantism and the Greek Church. And he concludes the book by confessing that he has sought to be admitted to a Belgian monastery.

Later on, however, Strindberg publicly declared that he never wished to seek consolation in the Catholic Church.

THE WORLD’S NEW ART CENTRE

FREDERICK JAMES GREGG

FROM JANUARY 1915

New York is now, for the time being at least—the art capital of the world, that is to say, the commercial art centre, where paintings and sculptures are viewed, discussed and purchased and exchanged.

Many predictions had been made, from time to time, as to when this state of affairs would come about. For years the drift of “old masters” has been Westward. Dr. Bode of Berlin, and other experts, had talked about the danger represented by the American buyer as competitor, in the open market, with the public galleries of Europe, limited as the latter were by slender resources and the niggardliness of parliaments. The London National Gallery and the Louvre have envied and feared the mighty resources of our Metropolitan Museum, which enabled it, at any moment, to pounce on whatever might emerge from private ownership—whether it was a newly discovered Rembrandt or a hitherto unsuspected collection of Chinese porcelains. So, while England, or France, was appealing to the patriotic to subscribe in order that some treasure might be kept from making the Atlantic voyage, word would come suddenly that the worst had happened, and that the dreadful Americans had scored again, thanks to the Rogers bequest or the alertness of some private benefactor.

The Great War—which has affected everything and everybody—hastened what prophets regarded as inevitable. Paris, London, Berlin and Petrograd, having the grim necessity of national self-preservation to attend to, simply went out of business as far as “art” was concerned.

The young painters and sculptors, like the young men in the picture-shops, are with the Colors. The exhibitions are all off. Hundreds of studios are locked up, and the cafés where the quarrelsome geniuses took their meals, and their ease, are but sad and quiet resorts of the casual and careless sightseer.

• • •

This is where technically neutral New York arose to her opportunity. For a while everything was up in the air, like Wall Street. But through patience and perseverance the tangle was straightened out. So the six weeks’ Matisse exhibition, planned to take place in the Montross Galleries in January, has become an assured fixture, and the set of exhibitions of the men of the younger French school at the Carroll Galleries will occur in the winter months just as if Europe, instead of being convulsed from one end to the other, were wrapped in profound peace. It is to be hoped that not many of the paintings will have to be hung with the customary purple.

New York will see, at the Matisse show, what the most discussed of all the Moderns regards as his most important, because most significant, work.

In the ultra Modern exhibition, at the Carroll Galleries, will be seen the work of Gleizes, Jacques Villon; Derain, painter of the “Fenêtre sur Parc;” Redon, of the humming flowers; Chabaud, of the “Flock Leaving the Barn;” de Segonzac, Dufy, de la Fresnaye, Moreau, Marcel Duchamp, who staggered New York with his “Nude Descending the Stairs;” Rouault, Picasso in his successive “red,” “blue,” and “cubist” periods; de Vlaminck, Signac, Seurat, and Duchamp-Villon. There will also be total strangers to us like Vera, Valtet, Ribemont-Desseignes, Mare, Sala and Jacques Bon. In addition, the veteran impressionist master Renoir will make his bow to the public as a sculptor, with a figure in the round and a plaque.

One striking thing about the “new men” is the way in which they change from one medium to another, as Picasso and Jacques Villon with their etchings, Dufy with his wood engravings, Vera with his wood cuts and Mare with his book bindings. Perhaps, as far as our own artists are concerned, one result of the display of the creations of these Frenchmen will be to cause them to show what they have been doing in unexpected directions. The wood carvings of Arthur Davies and the wood engravings of Walt Kuhn would astonish most of those who are not familiar with the very private activities of these two artists.

• • •

There has been more quarreling about Henri Matisse than about any other individualist of our epoch. If Matisse were not convinced of his genius, he might well be reassured on the subject by listening to the shouts of “Impostor!” “Rogue!” “Knave!” with which he is greeted by those who don’t like him. But this solid artist, who looks more like a professor of biology than a painter, is quite undisturbed by such popular clamor. If it is dishonest to paint without regard to the rules, he is content to be considered dishonest. But—great virtue in your “but”—nobody knows where your blessed rules are to be found, not even the learned creatures who talk so much about them.

Matisse does not care whether or not they call him a charlatan. He considers his art perfectly sincere and simple. Take his method of etching a portrait. Days are taken up in observation of his subject. Then he sets to work rather elaborately. The result is put aside. The second attack shows still less detail. In the final effort—that for which the rest was but preparation—every non-essential has been eliminated—nothing is left but something which suggests rather the qualities than the externals of his model. In a word—even if such a comparison is dangerous—Matisse develops a work from the heterogeneous to the homogeneous, from the complex to the baldly simple.

He has obtained less recognition at home than abroad, though Marcel Sembat, the present Minister of Public Works, and, since the death of Jaures, the chief socialist leader, is an ardent collector of his works. On the occasion of his first exhibition at Vollard’s, the preface of the catalogue was written by no less official a person than Roger Marx, the editor of the “Gazette des Beaux Arts.” The fact that the dealer wanted to give greater prominence to the critic than to the painter caused a disturbance which had true farce-comedy features, but Matisse won—on points.

The following proves nothing. But facts which are inconclusive, logically, are often interesting. Many of the Rembrandts, for instance, now in the Altman collection—which is the most gorgeous possession of our Metropolitan Museum—were, some years ago, the property of Alphonse Kann. He got tired of “old brown varnish”—people will get tired of everything, no matter how classical—and to-day he buys only Matisses. One of his proudest possessions is the nude, “with the blue leg,” a painting which, shown in the International Exhibition of 1913, surprised New York, disgusted Chicago and horrified Boston. Still M. Kann, if he felt it necessary to defend himself from the sneers of the scornful, might point out that Matisse is safely enshrined, through his drawings in the French Museums; that, other drawings, in spite of the notorious and aggressive conservatism of the Kaiser, are in the Print Cabinet at Berlin, and that he is more sought after by German collectors than any of the other “new” Frenchmen. Two characteristic paintings of prime importance, which will be seen in the Montross exhibition are the “Woman at a Desk” and “The Gold-fish.” These are the property of a Moscow collector. As, owing to the war, it was impossible to send them to their owner, Mr. Matisse decided, after some urging, to allow them to come to America, provided they didn’t go further West than New York.

• • •

Soon after the war broke out Matisse lost all trace of his mother, his brother and his brother’s family, who lived at his birthplace, Le Cateau, in the Nord. For months he could not work. He went to his country home, from which he was recalled to Paris to make selections for his New York exhibition. This took his mind off his family troubles. By this time he is probably in active service, for, in spite of his rheumatism, he was determined to get to the war. If he envies a soul in the world it is the painter Derain who went out in the artillery, was wounded, returned to Paris, and has now gone back to the trenches.

ARE ODD WOMEN REALLY ODD?

HYMAN STRUNSKY

FROM JUNE 1915

An odd creature has lately made its appearance on the horizon of man’s world. Scientists have craned their necks in the effort to determine its species, and psychologists have offered many conflicting explanations of its nature.

Was it man or was it woman?

Was it brute or was it human? Was it—What?

Inasmuch as it stood erect and glided with ease and in a spirit of independence, it suggested man; but it lacked man’s salient characteristics and coarser habits. Its shape and beauty—the clearness of the skin and the softness of the eyes—were decidedly womanly, but it lacked woman’s love of frills, her thirst for gossip, and her aptitude for useless occupations.

There was nothing about it to suggest the brute. It did not profane nor debauch; it did not utter coarse oaths, nor did it resort to violence. It was not human, in the sentimental meaning of the word. It did not cry nor did it whimper; it did not pout nor did it frown; it did not cuddle with weakness, or even crouch with fear.

Close observation, careful scrutiny and much wrangling, established the fact that the creature was a woman, after all, but an odd one! Gissing even wrote a book about her and called it “Odd Women.” Other authors followed him. H. G. Wells, for instance. G. B. Shaw, May Sinclair, W. L. George and a hundred lesser literary lights have all taken a shy at the “Odd” woman.

Especially does she appear odd to Madame X., the old fashioned woman, who has been slumbering under the impression that there was nothing at all odd about her own type of womanhood. Mrs. X. finds it a bit disturbing.

• • •

Woman’s historical position does not invite critical analysis. The fact is that men have not been treating her fairly. We very chivalrously called our wife our “better half,” but always regarded her as an inferior and kept her in strict subordination.

She was not a partner to the man, but an auxiliary, she was an extension to man, man, the gigantic structure; the centre of the universe. When we spoke of her “virtues,” we usually meant such of her characteristics as were pleasing and gratifying to us. Obedience, self-sacrifice, beauty, fidelity, tenderness, and affection, were qualifications highly valued,—because of their contributive share to the general happiness of husbands.

She was not master of herself. Her body belonged to her husband, her heart to her children, her mind to her home. Her sex was her sole means of subsistence. From the arms of an indulgent father she passed on to the shoulders of a supporting husband. Her function was to breed children and to amuse men. Whether poor or rich she was in a state of dependence. When poor she was a slave in a hovel; when rich she was an inmate of a glorified Doll’s House.

Marriage was her only trade, and like all other trades it was subject to the fluctuations caused by the law of supply and demand. The supply happened to overlap the demand and the market suffered a slump. Wise and knowing parents took charge of the matrimonial arrangements of their children. In these arrangements matters of convenience figured more prominently than questions of the heart. Love was too delicate a substance to attract the parent eye. Sexual selection, a biological play of emotion and passion—on which depends the make-up of posterity—was crowded out by “practical” considerations. The daughter was not to obey her instincts, but her parents. Disobedience meant—for the daughter—celibacy, and celibacy meant economic dependence.

• • •

The odd woman has odd notions about marriage, the oddest of which is that she thinks it is largely her own affair. To her, marriage is more than the privilege to indulge in dutiful submission. It is a matter of instinct in which her womanhood is involved, and unless she can have it beautifully she will not have it at all.

She is willing to give her labor and strength in exchange for a livelihood but she draws the line on the surrender of her soul. To obey parents is noble, but the will of the parent is the voice of the past and marriage is the demand of the future. The nuptial tie is not to mean the shackling of hearts, and a child is not to be the offspring of a business transaction. If celibacy threatens to lead to economic dependence then she will simply accept other trades as a means of subsistence.

She has at last found these other trades. Marriage is now not her only means of support.

She has discovered that there are other vocations besides being a wife. She has become a worker; a useful member of society; a fellow citizen in an industrial democracy. She is not the inferior but the equal of man. With him she enters the workshop, the library, the college. She writes books and edits magazines. She practices law and medicine. She paints pictures and takes photographs. She is a chemist, a geologist, a biologist, a stenographer, a decorator, a designer. She is a manufacturer. She owns farms and runs hotels. She is a lecturer and an actress. She is a teacher. She is a buyer. She is—odd!

Extremely odd—when judged by Madame X., whose frailties and weaknesses have heretofore constituted our standard of womanhood. We do not shrug our shoulders in deprecation at Madame X., who sleeps late, eats much, plays often and works seldom. We do not think it wrong of her to spend her best hours in the occult devices of the boudoir, where manicurists and masters of tonsorial art are mustering her faculties to the requirements of her social functions, and repairing, with color and cream, the ravages of Habit and Time.

• • •

Madame X. regards the odd women with amazement because they are different; because they rise early, play little, work much, make money, and are seldom idle.

Whether the odd woman is in business, or in a profession, she is beginning to earn a high salary and to stoop to no man in economic independence. She lives in a comfortable apartment and has a small place in the country. When her parents, or friends, are in need she assists them without suffering the humiliation of wheedling the money from her husband. Her contributions to charity are not the cause of “scenes” at breakfast. She is capable, efficient, and able to stand on her own feet. She is not a passive, but an active, member of society. Life is to her—what it should be to all women—a busy and strenuous experience.

Not long ago, in New York, two “odd” women—an authoress and a painter—were discussing Madame X. The authoress was describing to the painter a routine day in Madame X.’s life: Her pleasures, her dresses, her auction parties, her dances, her gossip, at luncheons, her race-meets and her susceptible admirers.

The authoress paused in her recital:

“And is that really her life?” asked the painter. “What an odd woman she must be.”

NEW YORK WOMEN WHO EARN $50,000 A YEAR

ANNE O’HAGAN

FROM AUGUST 1915

It is more than probable that, during the months of June and July, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue for New York has become convinced that the earning capacity of New York women is a fairly good reason for giving them the suffrage—in November. Perhaps, some day, he will let the world know to how many of the checks, sent by women in payment of their income tax, was attached one of those specially printed little blanks, which the suffragists have circulated so widely, reading: “I pay this tax under protest, in obedience to a law in the making of which I had no voice.”

A few weeks ago, the editor of this magazine [Frank Crowninshield] stated, in a widely contradicted address, that he knew, personally, a dozen women in New York who were earning over $50,000 a year by their own talents or industry. He said that he also knew fifty more who were earning $10,000 a year, or over. His statement was widely ridiculed and challenged, by many newspapers, and space writers, and by a host of conservative persons (whose social ideas had ceased to develop at the end of President Hayes’s administration, or thereabouts). They sought to convince the editor that the clever—and presumably beautiful—ladies had a little deceived him.

• • •

This writer has just completed a limited investigation into the question of the earnings of successful New York women. And she is quite convinced that without any exploring of New York’s by-ways, the editor’s statement was, in reality, a mild one.

Take for example, the playwrights.

Miss Jean Webster is a modest woman and wouldn’t for worlds make anarchists and bomb-throwers of the envious rest of us by telling exactly what she earns. But she does permit herself to say that from $500.00 to $700.00 a week is what “Daddy-Long-Legs,” in the hands of a single company, nets her as the author of it. Well, there have been several companies playing “Daddy-Long-Legs” for the greater part of the past year. There are, in addition, royalties on the moving picture rights of it, royalties upon it in book form, princely prices for other work, a serial and several short stories from her pen—and other side issues to swell the youthful playwright’s income, during the past year, to a figure a little over $50,000.

Since we began with playwrights let us go on with them.

There is “Twin Beds” continuing for Margaret Mayo—Mrs. Edgar Selwyn—the beneficent work of endowment which her first farce, “Baby Mine” began for her, a few years ago. Mrs. Selwyn has had several $50,000 years, and more are in store for her.

Then—but not in the $50,000 class—there is Eleanor Gates, whose “Poor Little Rich Girl” not only gave great delight to New York’s jaded public, a winter ago, but made her a comfortably rich little girl herself. And then there is Rachel Crothers. Or consider the case of Kate Douglas Wiggin—whose “Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm” laid a neat fortune in her lap when it went upon the boards, after following as a book, the filial example of “The Birds’ Christmas Carol” and the Penelope stories in laying treasures of love and admiration there. And if Mrs. Francis Hodgson Burnett, down at her place on Long Island, fails to feel the financial security of a steel magnate, with “Sara Crewe” and “Little Lord Fauntleroy” and the “Dawn of a To-morrow” defying time and change—but the thing is unthinkable.

• • •

And since we are speaking of the stage, what of the actresses? In what golden chariots may they not ride during the period of their prosperity, and ever after, if they are but wise and thrifty! That printed slip of defiance to the income tax commissioner seems tame when one considers what Miss Maude Adams or Miss Ethel Barrymore might say—or Laurette Taylor, or Ruth Chatterton, or Billie Burke, or Jane Cowl, or Frances Starr, or Margaret Illington, or Margaret Anglin, or Dorothy Donnelly or Chrystal Herne, or many, many less resplendent twinklers in the theatrical sky.

And the vaudeville favorites! There are, literally, a dozen of them who earn more than ten thousand dollars, like Gertrude Hoffmann, or Beatrice Herford, or Nora Bayes, or Nazimova, or Calve, for instance. Chief among them is Eva Tanguay whose salary is somewhere between $50,000 and $75,000 a year.

As for the film actresses, they are out of the Arabian Nights, no less! Think of the Mary Pickfords of $100,000 a year, and Marguerite Clarks at over $50,000 and the Mary Fullers, Lottie Briscoes, Pearl Whites, Anita Stewarts, Ruth Rowlands, Irene Fenwicks, Marie Doros, Pauline Fredericks, and many others at salaries which take one’s breath away.

Marie Doro, more or less of a novice on the films, has recently received an offer by a responsible firm—of $100,000 a year. She has earned within the past year, by acting and movies, as much as $4,000 in ten days.

• • •

Miss Geraldine Farrar is acting for the “movies” for two months this summer at a fabulous salary. Next winter she will receive $2,500 a performance for singing in opera or concert. This says nothing of her royalties on phonograph records. Think of Lucrezia Bori and Miss Ober, and the other opera singers. One of the impresarios, who has managed many concert and opera singers, furnishes a careful estimate of the incomes of only a few of them thus: Alma Gluck, $75,000 a year; Schumann-Heink, $85,000; Emmy Destinn, $50,000; Julia Culp, $20,000; Frances Alda, $25,000; Gadski, $30,000; Fremstad, $30,000; Caroline Hudson Alexander, $10,000. These sums only represent the earnings of ordinary concert work; what would be added to them by including the fees and royalties from records made for the talking machine companies, one’s dazed mathematical faculties fail to compute. Through the making of records, even the comparatively modest incomes of violinists, like Kathleen Parlow’s and Maude Powell’s ten-to-fifteen-thousand dollars-a-year, are greatly increased.

Alma Gluck, during the past twelve months, has probably earned more money than any woman alive. She is, today, the most popular singer in the phonograph. Her total income, from concerts and records, has considerably exceeded $120,000.

Before we leave the stage and turn to the more prosaic occupations in which women are laying up wealth, let us look at the dancers! How much do women like Mrs. Vernon Castle, or Pavlowa, make? It has been carefully computed that Mrs. Castle and her husband have earned more than $110,000 during the past twelve months. Following after Mrs. Castle are Joan Sawyer and Florence Walton, and Bessie Clayton and a half dozen others.

And then there are the women writers! There are many of these who earn $10,000 a year even without help from the dramatization of their work. Fannie Hurst is one of the authoresses among those present at any gambol on Mt. Croesus of ten-thousand-dollar women. Take Elizabeth Jordan, editor and writer. Consider Gertrude Atherton—she is a New Yorker now—and those strong, colorful novels of hers. And Edna Ferber, and Kathleen Norris, and Mrs. Riggs, and Gene Stratton Porter and a dozen others. Take even the woman publicist, who does not expect to rank financially with those writers whose function is primarily to amuse; she, also (Miss Ida Tarbell, for instance) does not find ten thousand a year a goal at all impossible of attainment.

And the ladies who illustrate. If May Wilson Preston, one of those rare human beings who may claim to be a satirist and a humorist with the pencil, demanded, instead of the beggarly ten or fifteen thousand dollars which she now earns, a hundred thousand a year, it would not be her admiring public which would demur or call her claim too large!

• • •

Then there’s Helen Dryden, who does covers, and fashion pictures, and who designs costumes for Mr. Dillingham. And there is Rose O’Neill Wilson, the mother of all the Kewpies. Once the Kewpie pictures and dolls were the whole Kewpie family. But now, with factories turning out Kewpie dolls, Kewpie dishes, boxes, jewelry, candy, clocks, clothes, post-cards, toys—and with Mrs. Wilson receiving royalties on every one of them, it is safe to say that she has long ago passed the $50,000 mark.

And the artists and portrait painters! What about Cecilia Beaux and Mrs. Rand and Miss Emmet, and others like unto them? And the sculptors, like Mrs. Whitney and Evelyn Longman! Ten thousand dollars a year would be meagre pay for them.

But all these women—the conservative man is likely to object—have unusual talents—genius; an afflatus apart from the gift of mere industry. But we are ready for him. We beg him to look at the heads of schools, business enterprises, of cigarette factories, of decorating establishments, of dressmaking houses.

What does he say to the schools in New York like those built up by Mrs. Finch (now Mrs. Cosgrave), by Miss Clara Spence, Miss Chapin, Miss Marie Bowen, Miss Rutz-Rees, and many more? That schools like these earn multiples of $10,000 a year cannot be denied.

And what will the conservative man say to women like Miss Belle Greene, who is officially the librarian of the late J. Pierpont Morgan’s library, but who was also his able lieutenant in all the work pertaining to his various collections?

And what about Mrs. M. E. Alexander, the pioneer woman in the New York real estate business, of whom it is recorded that she put through, for her employer, a $90,000 deal during the first two months (and the last) of her apprenticeship? Mrs. Alexander, after that pleasant demonstration of her fitness for the business she had chosen, went into it for herself!

And then there are the dressmakers and milliners—to call them by names too prosaic for their bewildering products. What is to be said of Lucille, Louise, Simcox, Mollie O’Hara, McNally, Farquharson & Wheelock (both women), Van Smith, the Fox Sisters, and a score of others like unto them who have proved themselves not only designers and saleswomen, but labor-managers as well? One of them, Mrs. Simcox, spoke for them all when she smilingly declared that a woman in her line of business would consider herself a failure if she were not clearing more than ten thousand a year.

What about play brokers and managers, like Miss Elizabeth Marbury? How many times does the gentleman with views on the financial inability of women think that that hard-working lady multiples our figure of $10,000 a year? And there are others in her profession, like Miss Alice Kauser, who forge along at a not too great distance behind.

Consider the growing horde of women decorators. Miss Elsie de Wolfe would think it a poor year if she did not clear $50,000 in profits. There are half a dozen more New York women—like Miss Swift, or Mrs. Rand, for instance, who are treading upon one another’s heels in achieving success in the same profession.

A little over a year ago a building was in course of construction upon Fifth Avenue. A woman had taken the land on forty-two years’ lease, and she was putting up the building. She was putting it up with earnings from her tea-rooms. It was only twelve years ago that Miss Ida L. Freese came to New York from Ohio, with no business training. To-day she runs her building, tea-rooms, a photographic studio and a farm, whence come the vegetables used in her restaurants.

When your true conservative smokes one of “Brennig’s Own” cigarettes does he realize that it is a woman’s enterprise which places it between his lips? Mrs. Brennig’s annual income—derived from her cigarettes—is one which has long ago tripled our modest $10,000 minimum.

When the reader eats “Mary Elizabeth’s” candy, or takes luncheon in “Mary Elizabeth’s” luncheon rooms, does he realize that twelve or fourteen years ago Mary Elizabeth Evans, a schoolgirl in Syracuse, began to put up home-made candies to help the family purse?

Even to the women who do not manage enterprises of their own, but who are valuable cogs in the great wheels of other people’s enterprises, ten thousand a year is no such unattainable goal. Mrs. Ray Wilner Sundelson, manager of an agency of the Equitable Life Insurance Company, is one of the highest salaried women in New York. She and fifteen thousand dollars a year have long been happily acquainted. And the management of a few department stores admit the presence of one or two women in their employ who qualify for this list—women buyers, department managers, advertising managers, and the like.

And there you are. In shop-keeping, hotel managing, teaching of singing and dancing, song writing, and in other branches of New York’s varied life, there are dozens of other women who earn, through their own talents or industry, at least $10,000 a year.

And we are only fifteen years advanced into the new century.

What will they earn when this century of marvels—with its great opportunities for women—draws to its close?

ANY PORCH

DOROTHY ROTHSCHILD (PARKER)

FROM SEPTEMBER 1915

Dorothy Parker’s first published poem

“I’m reading that new thing of Locke’s—

So whimsical, isn’t he? Yes—”

“My dear, have you seen those new smocks?

They’re nightgowns—no more, and no less.”

“I don’t call Mrs. Brown bad,

She’s un-moral, dear, not immoral—”

“Well, really, it makes me so mad

To think what I paid for that coral!”

“My husband says, often, ‘Elise,

You feel things too deeply, you do—’”

“Yes, forty a month, if you please,

Oh, servants impose on me, too.”

“I don’t want the vote for myself,

But women with property, dear—”

“I think the poor girl’s on the shelf,

She’s talking about her ‘career.’”

“This war’s such a frightful affair,

I know for a fact, that in France—”

“I love Mrs. Castle’s bobbed hair;

They say that he taught her to dance.”

“I’ve heard I was psychic, before,

To think that you saw it,—how funny—”

“Why, he must be sixty, or more,

I told you she’d marry for money!”

“I really look thinner, you say?

I’ve lost all my hips? Oh, you’re sweet—”

“Imagine the city to-day!

Humidity’s much worse than heat!”

“You never could guess, from my face,

The bundle of nerves that I am—”

“If you had led off with your ace,

They’d never have gotten that slam.”

“So she’s got the children? That’s true;

The fault was most certainly his—”

“You know the de Peysters? You do?

My dear, what a small world this is!”

FOOTBALL AND THE NEW RULES

WALTER CAMP

FROM SEPTEMBER 1915

With the actual preliminary football games of this season upon us, lovers of the game feel the necessity of becoming posted on the most important alterations in the rules. Spectators are not the only ones interested in this, for there are a great many players and some coaches who are by no means sure of even the most important changes.

The first addition to the machinery of the game which spectators will notice is the office of field judge. Last year this official was optional, but now he is obligatory. Moreover, the new rules have given the position of Field Judge a real significance by placing the watch of the time-keeper in his hands, with the idea that the linesman who kept time last year should concentrate his attention on the line-up during scrimmage. It is hoped that this new division of labor will make it easier for the officials to detect and penalize “off-side” play. Another rule, conceived with the idea of making things easier for the officials, and also to do away with the usual confusion in the last period of the game, is that which prevents the resubstitution of a player except at the beginning of a period. Last year everyone found it more or less annoying when, just before the end of the game, coaches sent in a whole army of substitutes. Aside from distracting the interest of the spectator, this indiscriminate mobilization on the side lines frequently resulted in the presence of a great number of non-combatants on the field of action when the ball was actually in play—an exceedingly confusing thing for the officials. Along these same lines the committee passed a note deprecating the custom of putting in substitutes for the purpose of conveying information to the team. The general practise of numbering the players was also recommended.

With regard to the conduct of the individual player, the penalty for unsportsmanlike conduct was changed from disqualification to a fifteen-yard setback, but flagrant misconduct is still punishable by disqualification. While this may seem to be too much power in the hands of the man with the whistle, it really ought to work out for the best interests of the game. Frequently, last year, when there was a reasonable doubt as to the actual intention of a player to willfully break the rules, the official was forced to let the offense go unpunished rather than inflict the drastic penalty of disqualification. Under the new ruling he can placate his conscience by compromising on the fifteen-yard penalty.

Before the rules were changed last year, running into the full-back in any way, intentionally or unintentionally, was penalized. Last season “roughing” the full-back was a “penal offense.” This year the rule has been clearly divided into two parts. Running into the full-back is penalized by a fifteen-yard set-back, but “roughing” the full-back not only penalizes the offending team fifteen yards, but in addition, disqualifies the player committing the offense.

A rule which has been added in order to do away with unnecessary delay is that which instructs the referee always to bring the ball out fifteen yards, when it goes out of bounds, unless the captain of the side in possession of the ball requests a lesser distance.

This year’s rules ring the curfew knell on the practise which started last year of intentionally throwing the ball out of bounds. The old rule provided that when a forward pass went out of bounds it went over to the team not in possession of the ball, at the spot where it crossed the side line. This made it possible for a team, on its opponent’s forty-five yard line (though not in a convenient position to make a field goal) to signal for a forward pass and throw the ball out of bounds somewhere near their opponent’s five-yard line. As a forward pass can naturally be executed more accurately than a kick, the result was that the opposing team, forced to put the ball into play at this point, and denied the chance which they would have had to run back the ball if it had been kicked, found itself in an uncomfortable position. This seemed to give an unfair advantage to the team making the pass. So it has been ruled that a forward pass which goes out of bounds, whether it touches a player or not, is an incompleted pass. In other words, the ball comes back to the line of scrimmage and counts as a down on the first, second and third tries. On the fourth try, it goes over to the opposing team on the line of scrimmage.

Another addition to the rules specifies that the interference will no longer be permitted to bowl over the secondary offense after the whistle blows. This practise was greatly abused last year. A half-back, on the defense, seeing the play stop in the line, would relax, when suddenly he would be struck from the side or from behind by a member of the interference who had been detailed to cross over from one side of the line and take the secondary defense. This was not only dangerous to the players, but frequently, in the more important games, came very near resulting in bad feeling. The interference, under the new rules, must stop when the whistle blows, and no man, either on the offense or defense, can run into a player after the referee has blown his whistle.

Another bad trick practised by the interference last year was for them to drop before a player, and throw their legs at him so that their feet and lower leg would strike the player across the body or thighs. This has resulted in several injuries. There is already a rule providing that if a player strikes his opponent below the knee with his lower leg it is “tripping.” The ruling now reads that a player who strikes another with his lower leg above the knee costs his side a penalty of fifteen yards.

One other play has been legislated against. In this play the center would start to pass the ball back, hold it for a fraction of a second, and then snap it to another lineman, who would come around and carry it. This year, when the center makes the motion to snap the ball back, he must actually let it go.

One other rule has been most properly altered—the rule relating to a player touching a forward pass. Last year this rule was altogether too severe. When two men were both eligible to receive the pass, and one of them touched the ball, the second player had to keep his hands off it or be penalized. This seemed somewhat unjust, and the rule has been altered so that a case of this sort is simply an incompleted forward pass, with the loss of a down, but no penalty to the second player.

To be letter-perfect in these rules, and at the same time to have the sharpness of vision, the rapidity of thought, and the clearness of purpose necessary to rule under them, is the task of the football official.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

EUR 5,27 expédition depuis Etats-Unis vers France

Destinations, frais et délaisAcheter neuf

Afficher cet articleEUR 6,85 expédition depuis Etats-Unis vers France

Destinations, frais et délaisRésultats de recherche pour Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best...

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.82. N° de réf. du vendeur G014312790XI4N00

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.82. N° de réf. du vendeur G014312790XI4N00

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.82. N° de réf. du vendeur G014312790XI4N00

Quantité disponible : 2 disponible(s)

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.82. N° de réf. du vendeur G014312790XI4N00

Quantité disponible : 2 disponible(s)

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.82. N° de réf. du vendeur G014312790XI2N00

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells : The Best of Early Vanity Fair

Vendeur : Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, Etats-Unis

Etat : Good. Reprint. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. N° de réf. du vendeur 8675768-6

Quantité disponible : 3 disponible(s)

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair

Vendeur : UBUCUU S.R.L., Bucharest, Roumanie

Paperback. Etat : Good. Reprint. N° de réf. du vendeur G-9780143127901-3

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair

Vendeur : California Books, Miami, FL, Etats-Unis

Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur I-9780143127901

Quantité disponible : Plus de 20 disponibles

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells

Vendeur : Rarewaves USA, OSWEGO, IL, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur LU-9780143127901

Quantité disponible : Plus de 20 disponibles

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells

Vendeur : Rarewaves.com UK, London, Royaume-Uni

Paperback. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur LU-9780143127901

Quantité disponible : Plus de 20 disponibles