Articles liés à Angle of Repose

Synopsis

Book by Stegner Wallace

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Extrait

Grass Valley

Now I believe they will leave me alone. Obviously Rodman came up hoping to find evidence of my incompetence--though how an incompetent could have got this place renovated, moved his library up, and got himself transported to it without arousing the suspicion of his watchful children, ought to be a hard one for Rodman to answer. I take some pride in the way I managed all that. And he went away this afternoon without a scrap of what he would call data.

So tonight I can sit here with the tape recorder whirring no more noisily than electrified time, and say into the microphone the place and date of a sort of beginning and a sort of return: Zodiac Cottage, Grass Valley, California, April 12, 1970.

Right there, I might say to Rodman, who doesn't believe in time, notice something: I started to establish the present and the present moved on. What I established is already buried under layers of tape. Before I can say I am, I was. Heraclitus and I, prophets of flux, know that the flux is composed of parts that imitate and repeat each other. Am or was, I am cumulative, too. I am everything I ever was, whatever you and Leah may think. I am much of what my parents and especially my grandparents were--inherited stature, coloring, brains, bones (that part unfortunate), plus transmitted prejudices, culture, scruples, likings, moralities, and moral errors that I defend as if they were personal and not familial.

Even places, especially this house whose air is thick with the past. My antecedents support me here as the old wistaria at the corner supports the house. Looking at its cables wrapped two or three times around the cottage, you would swear, and you could be right, that if they were cut the place would fall down.

Rodman, like most sociologists and most of his generation, was born without the sense of history. To him it is only an aborted social science. The world has changed, Pop, he tells me. The past isn't going to teach us anything about what we've got ahead of us. Maybe it did once, or seemed to. It doesn't any more.

Probably he thinks the blood vessels of my brain are as hardened as my cervical spine. They probably discuss me in bed. Out of his mind, going up there by himself . . . How can we, unless . . . helpless . . . roll his wheelchair off the porch who'd rescue him? Set himself afire lighting a cigar, who'd put him out? . . . Damned old independent mule-headed . . . worse than a baby. Never consider the trouble he makes for the people who have to look after him . . . House I grew up in, he says. Papers, he says, thing I've always wanted to do . . . All of Grandmother's papers, books, reminiscences, pictures, those hundreds of letters that came back from Augusta Hudson's daughter after Augusta died . . . A lot of Grandfather's relics, some of Father's, some of my own . . . Hundred year chronicle of the family. All right, fine. Why not give that stuff to the Historical Society and get a fat tax deduction? He could still work on it. Why box it all up, and himself too, in that old crooked house in the middle of twelve acres of land we could all make a good thing out of if he'd consent to sell? Why go off and play cobwebs like a character in a Southern novel, out where nobody can keep an eye on him?

They keep thinking of my good, in their terms. I don't blame them, I only resist them. Rodman will have to report to Leah that I have rigged the place to fit my needs and am getting along well. I have had Ed shut off the whole upstairs except for my bedroom and bath and this study. Downstairs we use only the kitchen and library and the veranda. Everything tidy and shipshape and orderly. No data.

So I may anticipate regular visits of inspection and solicitude while they wait for me to get a belly full of independence. They will look sharp for signs of senility and increasing pain--will they perhaps even hope for them? Meantime they will walk softly, speak quietly, rattle the oatbag gently, murmuring and moving closer until the arm can slide the rope over the stiff old neck and I can be led away to the old folks' pasture down in Menlo Park where the care is so good and there is so much to keep the inmates busy and happy. If I remain stubborn, the decision may eventually have to be made for me, perhaps by computer. Who could argue with a computer? Rodman will punch all his data onto cards and feed them into his machine and it will tell us all it is time.

I would have them understand that I am not just killing time during my slow petrifaction. I am neither dead nor inert. My head still works. Many things are unclear to me, including myself, and I want to sit and think. Who ever had a better opportunity? What if I can't turn my head? I can look in any direction by turning my wheelchair, and I choose to look back. Rodman to the contrary notwithstanding, that is the only direction we can learn from.

Increasingly, after my amputation and during the long time when I lay around feeling sorry for myself, I came to feel like the contour bird. I wanted to fly around the Sierra foothills backward, just looking. If there was no longer any sense in pretending to be interested in where I was going. I could consult where I've been. And I don't mean the Ellen business. I honestly believe this isn't that personal. The Lyman Ward who married Ellen Hammond and begot Rodman Ward and taught history and wrote certain books and monographs about the Western frontier, and suffered certain personal catastrophes and perhaps deserved them and survives them after a fashion and now sits talking to himself into a microphone--he doesn't matter that much any more. I would like to put him in a frame of reference and comparison. Fooling around in the papers my grandparents, especially my grandmother, left behind, I get glimpses of lives close to mine, related to mine in ways I recognize but don't completely comprehend. I'd like to live in their clothes a while, if only so I don't have to live in my own. Actually, as I look down my nose to where my left leg bends and my right leg stops, I realize that it isn't backward I want to go, but downward. I want to touch once more the ground I have been maimed away from.

In my mind I write letters to the newspapers, saying Dear Editor, As a modern man and a one-legged man, I can tell you that the conditions are similar. We have been cut off, the past has been ended and the family has broken up and the present is adrift in its wheelchair. I had a wife who after twenty-five years of marriage took on the coloration of the 1960s. I have a son who, though we are affectionate with each other, is no more my true son than if he breathed through gills. That is no gap between the generations, that is a gulf. The elements have changed, there are whole new orders of magnitude and kind. This present of 1970 is no more an extension of my grandparents' world, this West is no more a development of the West they helped build, than the sea over Santorin is an extension of that once-island of rock and olives. My wife turns out after a quarter of a century to be someone I never knew, my son starts all fresh from his own premises.

My grandparents had to live their way out of one world and into another, or into several others, making new out of old the way corals live their reef upward. I am on my grandparents' side. I believe in Time, as they did, and in the life chronological rather than in the life existential. We live in time and through it, we build our huts in its ruins, or used to, and we cannot afford all these abandonings.

And so on. The letters fade like conversation. If I spoke to Rodman in those terms, saying that my grandparents' lives seem to me organic and ours what? hydroponic? he would ask in derision what I meant. Define my terms. How do you measure the organic residue of a man or a generation? This is all metaphor. If you can't measure it, it doesn't exist.

Rodman is a great measurer. He is interested in change, all right, but only as a process; and he is interested in values, but only as data. X people believe one way, Y people another, whereas ten years ago Y people believed the first way and X the second. The rate of change is therefore. He never goes back more than ten years.

Like other Berkeley radicals, he is convinced that the post-industrial post-Christian world is worn out, corrupt in its inheritance, helpless to create by evolution the social and political institutions, the forms of personal relations, the conventions, moralities, and systems of ethics (insofar as these are indeed necessary) appropriate to the future. Society being thus paralyzed, it must be pried loose. He, Rodman Ward, culture hero born fully armed from this history-haunted skull, will be happy to provide blueprints, or perhaps ultimatums and manifestoes, that will save us and bring on a life of true freedom. The family too. Marriage and the family as we have known them are becoming extinct. He is by Paul Goodman out of Margaret Mead. He sits in with the sitter-inners, he will reform us malgré our teeth, he will make his omelet and be damned to the broken eggs. Like the Vietnam commander, he will regretfully destroy our village to save it.

The truth about my son is that despite his good nature, his intelligence, his extensive education, and his bulldozer energy, he is as blunt as a kick in the shins. He is peremptory even with a doorbell button. His thumb never inquires whether one is within, and then waits to see. It pushes, and ten seconds later pushes again, and one second after that goes down on the button and stays there. That's the way he summoned me this noon.

I responded slowly, for I guessed who it was: his thumb gave him away. I had been expecting his visit, and fearing it. Also I had been working peacefully and disliked being disturbed.

I love this old studio of Grandmother's. It is full of sun in the mornings, and the casual apparatus and decorations of living, which age so swiftly in America, have here kept a worn, changeless comfortableness not too much violated by the tape recorder and the tubular desk light and other things I have had to add. When I have wheeled my chair into the cut-out bay in the long desk I can sit surrounded on three sides by books and papers. A stack of yellow pads, a mug of pens and pencils, the recorder's microphone, are at my elbow, and on the wall before my face is something my grandmother used to have hanging there all through my childhood: a broad leather belt, a wooden-handled cavalry revolver of the Civil War period, a bowie knife, and a pair of Mexican spurs with 4-inch rowels. The minute I found them in a box I put them right back where they used to be.

The Lord knows why she hung them where she would see them every time she looked up. Certainly they were not her style. Much more in her style are the trembling shadows of wistaria clusters that the morning sun throws on that wall. Did she hang them here to remind herself of her first experience in the West, the little house among the liveoaks at New Almaden where she came as a bride in 1876? From her letters I know that Grandfather had them hanging there in the arch between dining room and parlor when she arrived, and that she left them up because she felt they meant something to him. The revolver his brother had taken from a captured rebel, the bowie he himself had worn all through his early years in California, the spurs had been given to him by a Mexican packer on the Comstock. But why did she restore his primitive and masculine trophies here in Grass Valley, half a lifetime after New Almaden? Did she hang those Western objects in her sight as a reminder, as an acknowledgment of something that had happened to her? I think perhaps she did.

In any case, I was sitting here just before noon, contented in mind and as comfortable in body as I am ever likely to be. The slight activity of rising and breakfasting, which I do without Ada, and the influence of coffee and the day's first aspirin, and the warmth of the sun against my neck and left side, these are morning beneficences.

Then that thumb on the bell.

I pushed back from among the sun-dazzled papers and rotated my chair. Two years' practice has not fully accustomed me to the double sensation that accompanies wheelchair locomotion. Above, I am as rigid as a monument; below, smooth fluidity. I move like a piano on a dolly. Since I am battery-powered, there is no physical effort, and since I cannot move my head up, down, or to either side, objects appear to rotate around me, to slide across my vision from peripheral to full to opposite peripheral, rather than I to move among them. The walls revolve, bringing into view the casement windows, the window seat, the clusters of wistaria outside; then the next wall with photographs of Grandmother and Grandfather, their three children, a wash drawing of the youngest, Agnes, at the age of three, a child who looks all eyes; and still rotating, the framed letters from Whittier, Longfellow, Mark Twain, Kipling, Howells, President Grover Cleveland (I framed them, not she); and then the spin slows and I am pointed toward the door with the sunlight stretching along the worn brown boards. By the time I have rolled into the upper hall, my visitor is holding down the bell with one hand and knocking with the other.

Though I have got handier in the ten days I have been here, it took me a minute to get into position over the brace that locks my chair onto the lift, and I felt like yelling down at him to for God's sake let up, I was coming. He made me nervous. I was afraid of doing something wrong and ending up at the bottom in a mess of twisted metal and broken bones.

When I was locked in, I flipped the wall switch, and the lift's queer, weightless motion took hold of me, moved me smoothly, tipped me with the inevitable solar plexus panic over the edge. I went down like a diver submerging, the floor flowed over my head. Without haste the downstairs wall toward which my rigid head was set unrolled from top to bottom, revealing midway the print of that Pre-Raphaelite seadog and his enchanted boy listeners--a picture my grandmother might have painted herself, it is so much in her key of aspiration arising out of homely realism. Then I was level with the picture, which meant that my chair had come into view from the front door, and the ringing and pounding stopped.

The chair grounded in light as murky and green as the light of ten fathoms: the ambition of that old wistaria has been to choke off all the lower windows. I tipped up the brace with one crutch, and groped the crutch back to its cradle on the side of the chair--and carefully, too, because I knew he was watching me and I wanted to impress him with how accidentproof my habits were. A touch on the motor switch, a hand on the wheel, and I was swinging again. The wall spun until Rodman's face came into focus, framed in the door's small pane like the face of a fish staring in the visor of a diver's helmet--a bearded fish that smiled, distorted by the beveled glass, and flapped a vigorous fin.

These are the results, mainly negative from his point of view, of Rodman's visit:

(1) He did not persuade me--nor to do him justice did he try very hard--to come back and live with them or start arrangements for the retirement home in Menlo Park.

(2) He did not persuade me to stop running around alone in my wheelchair. Sure I bumped my stump, showing off how mobile I am and how cunningly I have converted all stairs to ramps. Could he tell by my face how much I hurt, sitting there smiling and smiling, and wanting to take that poor sawed-off twitching lump of bones and flesh in my two hands and rock back and forth and grit my teeth and howl? What if he could? When I am not showing off to prove my competence to pe...

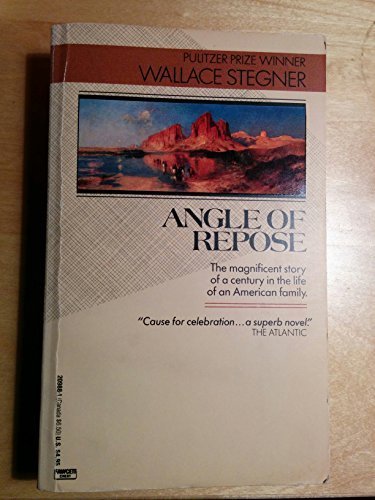

Présentation de l'éditeur

Wallace Stegner's Pultizer Prize-winning novel is a story of discovery—personal, historical, and geographical. Confined to a wheelchair, retired historian Lyman Ward sets out to write his grandparents' remarkable story, chronicling their days spent carving civilization into the surface of America's western frontier. But his research reveals even more about his own life than he's willing to admit. What emerges is an enthralling portrait of four generations in the life of an American family.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

EUR 3,89 expédition depuis Etats-Unis vers France

Destinations, frais et délaisAcheter neuf

Afficher cet articleEUR 25,48 expédition depuis Etats-Unis vers France

Destinations, frais et délaisRésultats de recherche pour Angle of Repose

Angle of Repose

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, Etats-Unis

Unknown. Etat : Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.61. N° de réf. du vendeur G0449209881I3N00

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Angle of Repose

Vendeur : Hamelyn, Madrid, M, Espagne

Etat : Aceptable. : Angle of Repose es una novela ganadora del Premio Pulitzer de Wallace Stegner que narra la historia de cuatro generaciones de una familia estadounidense mientras intentan construir una vida en el oeste americano. La novela sigue a Lyman Ward, un historiador retirado en silla de ruedas, mientras investiga la vida de sus abuelos y descubre secretos sobre su propia vida en el proceso. Una historia de descubrimiento personal, histórico y geográfico. EAN: 9780449209882 Tipo: Libros Categoría: Literatura y Ficción Título: Angle of Repose Autor: Wallace Stegner Editorial: Fawcett Idioma: en Páginas: 512 Formato: libro de bolsillo. N° de réf. du vendeur Happ-2025-06-23-4a368010

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Angle of Repose

Vendeur : Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, Etats-Unis

Etat : Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. N° de réf. du vendeur 3285956-6

Quantité disponible : 4 disponible(s)

Angle of Repose

Vendeur : Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, Etats-Unis

Etat : Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. N° de réf. du vendeur 3285956-6

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Angle of Repose

Vendeur : Goldstone Books, Llandybie, Royaume-Uni

mass_market. Etat : Good. All orders are dispatched within one working day from our UK warehouse. We've been selling books online since 2004! We have over 750,000 books in stock. No quibble refund if not completely satisfied. N° de réf. du vendeur mon0007462866

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Angle of Repose

Vendeur : Library House Internet Sales, Grand Rapids, OH, Etats-Unis

Softcover. Etat : Good. No Jacket. Piece(s) of the spine missing. Solid binding. Please note the image in this listing is a stock photo and may not match the covers of the actual item. Book. N° de réf. du vendeur 123523311

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Angle of Repose

Vendeur : The Book Garden, Bountiful, UT, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Good - Cash. General reader wear to the corners, edges, and cover. The covers, spine, and corners have some creasing and wrinkling. Notes inside front cover and on ffep. Many notations throughout text. The pages show some general reader wear as well. The book is in good condition with some normal reader wear. Stock photos may not look exactly like the book. N° de réf. du vendeur 1146997

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Angle Of Repose

Vendeur : Library House Internet Sales, Grand Rapids, OH, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Good. No Jacket. Traces the fortunes of four generations of one family as they attempt to build life for themselves in the American West. Due to age and/or environmental conditions, the pages of this book have darkened. Boards are moderate to severely edgeworn. Moderate shelf wear. Please note the image in this listing is a stock photo and may not match the covers of the actual item. Book. N° de réf. du vendeur 123624353

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Angle of Repose

Vendeur : Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, Etats-Unis

Etat : Very Good. Very Good condition. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. N° de réf. du vendeur W10C-02520

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Angle of Repose

Vendeur : SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, Etats-Unis

Etat : Acceptable. Item in acceptable condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. N° de réf. du vendeur 00073168384

Quantité disponible : 2 disponible(s)