Synopsis

The First New Translation in Forty Years

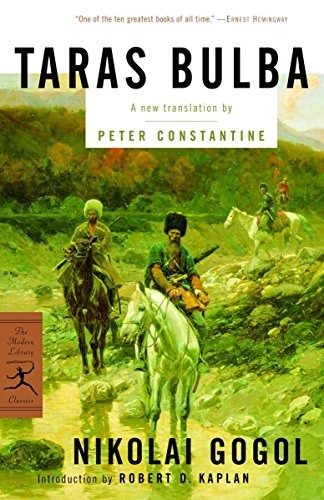

Set sometime between the mid-sixteenth and early-seventeenth century, Gogol’s epic tale recounts both a bloody Cossack revolt against the Poles (led by the bold Taras Bulba of Ukrainian folk mythology) and the trials of Taras Bulba’s two sons.

As Robert Kaplan writes in his Introduction, “[Taras Bulba] has a Kiplingesque gusto . . . that makes it a pleasure to read, but central to its theme is an unredemptive, darkly evil violence that is far beyond anything that Kipling ever touched on. We need more works like Taras Bulba to better understand the emotional wellsprings of the threat we face today in places like the Middle East and Central Asia.” And the critic John Cournos has noted, “A clue to all Russian realism may be found in a Russian critic’s observation about Gogol: ‘Seldom has nature created a man so romantic in bent, yet so masterly in portraying all that is unromantic in life.’ But this statement does not cover the whole ground, for it is easy to see in almost all of Gogol’s work his ‘free Cossack soul’ trying to break through the shell of sordid today like some ancient demon, essentially Dionysian. So that his works, true though they are to our life, are at once a reproach, a protest, and a challenge, ever calling for joy, ancient joy, that is no more with us. And they have all the joy and sadness of the Ukrainian songs he loved so much.”

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

À propos de l?auteur

Peter Constantine was awarded the 1998 PEN Translation Award for Six Early Stories by Thomas Mann and the 1999 National Translation Award for The Undiscovered Chekhov: Forty-Three New Stories, and has been widely acclaimed for his recent translation of the complete works of Isaac Babel. His translations of fiction and poetry have also appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s, Grand Street, Paris Review, Fiction, Harvard Magazine, Partisan Review, and London Magazine, among others. He lives in New York City.

Robert D. Kaplan is the bestselling author of twenty books on foreign affairs and travel translated into many languages, including Adriatic, The Good American, The Revenge of Geography, Asia’s Cauldron, Monsoon, The Coming Anarchy, and Balkan Ghosts. He holds the Robert Strausz-Hupé Chair in Geopolitics at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. For three decades he reported on foreign affairs for The Atlantic. He was a member of the Pentagon’s Defense Policy Board and the U.S. Navy’s Executive Panel. Foreign Policy magazine twice named him one of the world’s “Top 100 Global Thinkers.”

Extrait. © Reproduit sur autorisation. Tous droits réservés.

1

“Turn around and let me look at you! What a sight! What are you wearing there, a priest’s cassock or something? Is that how you run around at that academy of yours?”

These were the words with which old Bulba greeted his two sons, who, having completed their studies at the Seminary in Kiev, had come home to their father. The sons had just dismounted from their horses. They were robust young men, with the sullen look one sees in all Seminary students recently released. Their strong, healthy faces were covered with a first down that had not yet been touched by a razor. Embarrassed by the way their father welcomed them, they stared sullenly at the ground.

“Wait, wait! Let me get a good look at you!” Bulba continued, turning them around. “What are these long tunics you’re wearing, if you can even call them that? I’ve never seen the like! Take a few steps—I swear they’ll get caught between your legs, and you’ll go flying!”

“Don’t make fun of us, Papa!” the older of the boys finally said.

“Look how high and mighty he is! And why, pray, shouldn’t I make fun of you?”

“Because, well . . . even though you’re my papa, if you make fun of me, then by God I’ll thrash you!”

“Ha! You damn son of a you-know-what! Your own father?” Taras Bulba shouted, staggering back in surprise.

“Yes, even though you’re my father. Insult me, and I don’t care who you are!”

“So how do you want to fight, with your fists?”

“Any way you want!”

“Well then, show me your fists!” Taras Bulba said, pulling up his sleeves. “I’d like to see what kind of man you are with your fists!”

Father and son, instead of greeting each other after their long separation, began throwing punches at each other’s stomach and chest, stepping back to glare at each other and then attacking again.

“Neighbors, villagers!” shouted the boys’ pale, gaunt mother, who was standing on the threshold and had not had a chance to embrace her beloved children. “The old man’s gone mad! His mind’s unhinged! The boys come home, we haven’t seen them for over a year, and what does he do? Fly at them with his fists!”

“He fights well, this one!” Bulba gasped, stopping for a moment. “By God, he fights well!” he continued, catching his breath. “So well that I’d have done better not to test him. He’ll make a good Cossack, this one! I welcome you, my son! Let us kiss!”

And father and son kissed.

“Well done, my boy! You can get the better of any man if you go at him the way you went at me! Show mercy to no one. But I still think you’re wearing the oddest clothes I’ve ever seen! What’s this string hanging there? And you,” he shouted, turning to his younger son. “You Grand Padishah, why are you standing there with your arms dangling?* You son of a dog, aren’t you going to punch me too?”

* Padishah = “Great Emperor.” The title of the sultan of Turkey.

“What will he think of next?” the mother gasped, throwing her arms around the boy. “He wants his own flesh and blood to raise a hand to him! That’s all we need! The boy is young, has had a long journey, and must be exhausted!” (The boy was nearly twenty and well over six feet tall.) “He has to rest and eat a bite of food, and the old fool wants to fight him!”

“You’re a milksop, I see!” Bulba said. “Don’t listen to your mother, my boy! She’s a woman, she knows nothing! What do you need sweetness for? An open field and a good horse, that’s all the sweetness you need! You see this saber? This saber is your mother! They’ve been filling your heads with filth, that’s what they’ve been doing! The Seminary, and all those little books and primers and philosophy and the devil knows what else—I spit on it all!” And Bulba slipped in a word that cannot appear in print. “What I ought to do is send you this very week to Zaporozhe.* That’s where you will find some real learning. There you’ll get some schooling. There you’ll really learn something!”

“The boys are only staying home a week?” the distraught mother gasped, her eyes filling with tears. “The poor boys won’t even have a chance to enjoy themselves a little. They won’t have a chance to get to know their own home, and I won’t be able to get my fill of looking at them!”

“Enough! Enough whining, old woman! Cossacks aren’t Cossacks so they can hobnob with women! Given half a chance you’d hide them under your skirt and sit on them like a hen. Off with you, quick, and get the table ready! Lay out everything we have! No need for fritters and poppyseed cakes, or any other delicate little morsels; just bring out some mutton and some goat, and the forty-year-old mead. And some good vodka, none of that fancy liquor with raisins and other little knickknacks in it! I want my vodka so clear and frothing that it hisses and whirls like it’s possessed!”

* A settlement on the Dnieper in Ukraine, where the Zaporozhian Cossacks had their base camp, the Sech.

Bulba led his sons into the front room. Two pretty maids wearing

coin necklaces, who had been busy cleaning, dropped everything and ran. They were evidently frightened by the arrival of the young masters, who never let anyone alone, or else they simply wanted to stick to their girlish ways, squealing and bolting whenever they saw a man, lifting their sleeves to their faces, hiding them in shame. The front room was furnished in the taste of those difficult, warring times, when battles and skirmishes broke out because of the union with Poland. Living traces of those days are found only in the songs and folk epics sung in the Ukraine by old, bearded, blind men quietly strumming their banduras, surrounded by a crowd.* Everything was clean and brightly painted. On the walls hung sabers, whips, bird traps, fishnets, muskets, an intricately carved gunpowder horn, a golden bridle, and a hobble with silver pendants. The windows were small, with round, dim panes such as are now found only in old churches, and through which one could only see if one raised the movable panels. Red drapes hung by the windows and doors. On shelves in the corners stood pots, bottles, flasks of blue and green glass, ornate silver goblets, and gilded cups of every handicraft—Venetian, Turkish, Circassian—that had made their way into Bulba’s front room by many paths and through many hands, as was not unusual for those swashbuckling times. Birch benches ran along the walls in all the rooms. Beneath the icons in the prayer corner stood a massive table, and near it a stove with many ledges and protuberances, surrounded by warm benches. The stove was covered with bright multicolored tiles. All this was very familiar to the two young men, who in the past had walked home every year during the holidays because they did not yet have horses, and because it was not customary to allow students of the Seminary to ride. The only Cossack tradition they had kept was the long forelock, the chub, which seasoned Cossacks tugged at in jest.‡ Now that

* A bandura is a lutelike instrument used by Ukrainian bards to accompany sung ballads and epics.

† Circassia is a region in the northern Caucasus.

‡ Ukrainian Cossacks shaved their heads, leaving only a forelock, known as chub.

they had finished their studies, Bulba had sent them a pair of young stallions from his own herd.

To celebrate his sons’ arrival, Bulba called in all the Cossack captains and anyone from his regiment who was within reach. And when his old comrade Captain Dimitro Tovkach came with two officers, Bulba immediately presented his sons to them.

“Here—see what fine boys these are! I’ll be sending them to the Sech soon.”

The guests congratulated Bulba and the two young men, assuring them that it was a good idea, that there was no better schooling for young men than the Zaporozhian Sech.

“Well, my brothers, seat yourselves at the table wherever you like!” Bulba shouted, and turned to his sons. “First we shall down some vodka! God’s blessings upon you, and good health to the two of you! To you, Ostap, and to you, Andri! May God grant that success always follow you in battle, whether you fight heathen, Turk, or Tatar fiend. And if the damn Poles start plotting against our religion, then may you thrash them too! Come, hand me your cup! Good vodka, no? So how does one say ‘vodka’ in Latin? Ha! Well, my son, those Romans were fools—they didn’t even know there was such a thing as vodka! What was that fellow’s name again, the one who wrote little Latin ditties? I’m not much of a lettered man, so it’s not coming to me right now. Wasn’t it Horace, or something?”

“Ha, that’s my father for you!” Ostap, the older of the two boys, thought. “There’s nothing the old scoundrel doesn’t know, and yet he pretends not to.”

“It would surprise me if the Archimandrite at the Seminary let you have so much as a whiff of vodka,” Taras continued.* “And I trust you were given robust birch-wood and fresh cherry-wood whippings across your backs and your other Cossack parts! And perhaps the cleverer you got the more you got to taste the cat-o’-nine-tails. And

* Archimandrite: the head of a Russian Orthodox monastery or group of monasteries.

not only on Saturdays, I’m sure, but on Wednesdays and Thursdays too!”

“There is no reason to remember what was, Papa,” Ostap answered coolly. “What was is now past and gone!”

“I’d like to see them try something now!” Andri said. “I’d like to see someone so much as try to touch us. Let some Tatar dog cross my path, and I’ll teach him what a Cossack saber is!”

“Well spoken, my son! By God, well spoken indeed! When the time comes I will ride out by your side, by God I will! Why the devil should I sit around here? So I can sow buckwheat? So I can run the household, tend the sheep and pigs, and help the old woman with her sewing and needlework? To the devil with her! I’m a Cossack and will have none of this! So what if there’s no war, I’ll ride with you to Zaporozhe for some fun, by God I will!”

Old Bulba became increasingly heated, and finally burst into a rage. Then he stood up from the table, composed himself, and stamped his foot.

“We will leave tomorrow! There is no point in dawdling! What enemy can we expect to dig up here? What do we need this house for? What do we need all these pots for?” He began pounding the pots and bottles with his fist and hurling them across the room. His poor wife, used to her husband’s outbursts, looked on sadly from where she sat on the bench. She did not dare open her mouth, but when she heard his decision, so dreadful to her, she could not restrain her tears. She looked at her sons, from whom she was in danger of being parted so soon, and no one can describe the mute power of the sadness that trembled in her eyes and on her lips, which were convulsively pressed together.

Bulba was an uncommonly stubborn man. He was a character who could only have sprung forth from the harsh fifteenth century in that half-nomadic corner of Europe, when the whole of primitive Russia’s south, abandoned by its princes, was laid waste and left in ruins by the relentless onslaught of the Mongol marauders; it was a time when man, turned out of house and home, became dauntless, when he settled in charred ruins in the face of terrible neighbors and never- ending danger, learning to look them in the eye and unlearning that fear exists in the world; when the flames of war gripped the ancient peaceful Slavic spirit, and Cossackry—that wide, raging sweep of Russian character—was introduced, and when the Cossacks, no one knew their number, struck root along the rivers, at crossings, and on embankments. And when the Turkish Sultan asked how many Cossacks there were, he was told, “Who knows! They are scattered over the whole of our steppes. Behind every weed you’ll find a Cossack and his steed!” It was truly an extraordinary phenomenon of Russian power, arising from the national heart of fiery poverty. Instead of the former sovereign principalities consisting of small towns of hunters and trappers, instead of minor princes quarreling and trading with these towns, in their place menacing Cossack settlements and strongholds grew, linked by their shared danger and their hatred of the infidel marauders. We know from our history books how the Cossacks’ endless skirmishes and restless life saved Europe from the unstoppable infidel attacks that threatened to overthrow her.

The Polish kings who replaced the appanage princes found themselves lords of these wide lands. Far off and weak though they were, these kings understood the importance of the Cossacks and the advantages to be gained from the Cossack life of warring and defending. The Polish kings encouraged and flattered the Cossacks, and un- der their distant rule the Hetmans, chosen from among the Cossacks themselves, transformed their homesteads and huts into military bastions. Theirs was not a disciplined and organized army—there were none in that era. But in the case of war and a call to arms, within eight days and not a day more every Cossack presented himself in full armor on his horse, receiving only a single gold ducat in payment from the king, and within two weeks an army came together the like of which no recruiting force could have gathered. When the campaign ended, the warriors returned to their meadows and fields by the Dnieper crossings, fished, traded, brewed beer, and were free Cossacks. Foreigners of the time were astounded by the truly unusual capabilities of the Cossack. There was no craft he was not master of. He could distill vodka, harness a cart, and grind gunpowder; he was adept at blacksmithing and metalwork; and on top of all that, he could feast recklessly, drink, and carouse as only a Russian can.

Besides the registered Cossacks, who felt bound to present themselves in times of war, it was also possible in case of great urgency to gather crowds of eager volunteers. A Cossack captain had only to stroll through a market or across a village square and shout at the top of his voice, “Hey, you beer brewers! Enough of your brewing and lolling around on stove benches and feeding the flies with your fat carcasses! Ride out in quest of a knight’s glory and honor! You plowmen, buckwheat sowers, shepherds, and women-chasers! Enough following the plow, sloshing through the mud in your yellow boots, and crawling to women beneath the covers, squandering your knightly strength! It’s time to get yourself some Cossack glory!” And these words were like sparks falling onto dry wood. The plowman threw down his plow, the beer brewer pushed over his tubs and smashed his barrels, craftsmen and store owners sent to the devil all their crafts, all their stores, and all the pots in their houses. Anyone and everyone climbed onto his horse. In a word, the Russian character assumed a broad and powerful sweep.

Taras was one of the true old commanders. He was made for the alarms of war, and stood out for the rough straightforwardness of his temper. In those days the influence of Poland had already begun to have an effect on the Russian nobility. Many had adopted Polish customs, flaunting great pomp, keeping astonishing numbers of servants, falcons, huntsmen, feasts, and palaces. Taras did not crave these splendors. He loved the simple life of the Cossack, and quarreled with comrades who were drawn to the Warsaw faction, accusing them of being lackeys of the Polish noblemen. He was eternally restless. He saw himself as the lawful protector of the Russian Orthodox faith. He was quick to enter villages whenever the people complained of oppression by the landlords and the raising of chimney taxes. He and his Cossacks carried out reprisals. Taras lived by the rule that he was always ready to unsheathe his saber in three circumstances: when commissars did not show full respect to Cossack elders, such as not removing their hats in their presence; when anyone made light of the Russian Orthodox faith and ancestral laws; and, needless to say, when faced by heathens or Turks, against whom he felt it was proper to reach for his saber at all times in the name of Christendom.

Now Taras Bulba anticipated with pleasure how he would appear at the Sech with his two sons and say, “Look what splendid fellows I am bringing you!” and how he would present them to all his old, battle-hardened comrades. He saw himself watching the boys’ first feats in the military arts and in carousing, which he also considered as one of the foremost knightly virtues. He had originally intended to send his sons to the Sech alone, but their youth and vigor, their strength and physical beauty ignited his warrior’s spirit and he decided to go with them himself the very next day, though the only thing arguing for such an action was his obstinate will. He was already rushing about, giving orders, choosing horses and harnesses for his sons, visiting the stables and barns, picking servants who would ride out with them the following day. He left Captain Tovkach in charge, along with the stern order that Tovkach was to appear with the full regiment the instant he sent word from the Sech. Taras Bulba forgot nothing, even though he was still elated and the hops were bubbling through his head. He even ordered that the horses be given water and that the best and hardiest wheat be poured into their mangers. And he returned home tired from all his running around.

“Well, my boys! It’s time to get some rest now, and tomorrow we shall tackle whatever God sees fit to send us! No, don’t bother fixing our beds! We won’t be needing beds—we shall sleep out in the yard!”

Night had barely embraced the sky, but Bulba always went to sleep at an early hour. He lay down on a carpet and covered himself with a sheepskin coat, because the night air was quite chilly and because he liked to sleep as warmly as possible when he was at home. Soon he was snoring, and the whole yard followed suit. All those who were curled up in various corners began snoring and whistling. The first to fall asleep was the watchman, because he had drunk more than anyone else in honor of the young masters return.

Only the poor mother could not think of sleep. She bent over the pillows of her darling sons, who lay side by side, and combed their young, tousled locks, dampening them with tears. She gazed at them with all her being, with all her feelings. She gazed at them with all her heart and could not look her fill. Her breasts had fed them, she had raised them, cherished them, and now she was to see them but for a moment. “My sons, my darling sons! What will become of you? What fate awaits you?” she whispered, her tears stopping in the wrinkles that had transformed her once-beautiful face. She was in fact a sad figure, like all women of that distant century. She had only lived love for an instant, in the first flames of passion, the first flames of youth—and already her stern seducer turned away from her in favor of his sword, his comrades, and their carousing. One year she would see her husband for two or three days, and then many years would pass in which she neither heard nor saw anything of him. And even when she saw him, when they lived together, what kind of life was that? She had to bear his insults and beatings. The only caresses she knew were dealt her as alms; she was like a strange being among this medley of womanless knights upon whom dissipated Zaporozhe had cast its grim shadow. Her bleak youth had flashed past; her beautiful fresh cheeks and breasts, prematurely covered with wrinkles, had withered unkissed. All her love and feeling, all that is tender and passionate in woman, turned into maternal love. With fire, passion, and tears she hovered over her children like a gull. Her sons, her beloved sons, were now being taken away from her, taken away, and she would never see them again! Who knew, perhaps a Tatar would slice off their heads the first time they rode into battle, and she would never know where their bodies were thrown, their flesh pecked at by roadside birds of prey. She was ready to sacrifice all she had for each drop of their blood. Sobbing, she gazed into their eyes, which all-powerful sleep was beginning to close, and thought, “Perhaps when Bulba wakes up he might put off their leaving for a day or two. Perhaps it was just the drink that made him think of leaving so early.”

From the heights of the sky the moon illuminated the whole courtyard filled with sleeping men and the thick clumps of pussy willow and tall steppe grass that engulfed the paling around the yard. She sat by the heads of her sweet sons without taking her eyes from them for even an instant and without thinking of sleep. The horses, sensing the approach of dawn, had stopped grazing and lay down on the grass. The upper leaves of the pussy willows began to whisper, and gradually the whispering began to descend. She sat there until daybreak, not in the least tired, wishing deep inside that the night would last much longer. The gentle neighing of a foal sounded from the steppes. Strips of red stretched across the sky.

Bulba suddenly awoke and jumped to his feet. He remembered everything he had ordered done the night before.

“Well, my boys, you’ve had your share of sleep! Come on, it’s time to get going! Water the horses! Where’s the old woman?” (That was how he usually referred to his wife.) “Get a move on, old woman! Fix us something to eat—we have a long road ahead of us!”

The poor old woman, robbed of her last hopes, dragged herself dejectedly into the hut. Weeping, she busied herself preparing breakfast while Bulba shouted orders and headed to the stables to choose the best bridles for his sons’ horses. The young Seminary students had undergone quite a transformation. Instead of their old, bespattered boots, they were now wearing new red ones of morocco leather re- inforced with silver studs, and their trousers, wide as the Black Sea, with a thousand folds and pleats, were belted with a golden sash from which hung a long strap with tassels and other trinkets and to which their gunpowder horns were tied. Their scarlet Cossack jackets, the cloth bright as fire, were girded with ornate belts in which richly carved Turkish pistols were stuck. Their sabers swung against their legs. Their faces, little burnt by the sun, seemed handsomer and whiter, and their young black mustaches somehow underlined the paleness of the healthy, robust color of their youth. Their faces were striking beneath their tall, black, golden-topped lambskin hats. Their poor mother! She looked at them and could not utter a word, her tears trapped within her eyes.

“Well, my sons, everything is ready! There’s no point lingering!” Bulba finally pronounced. “Now, as Christian custom has it, we must all sit together one last time before we leave.”

And they all sat down together, even the lackeys who had been standing reverently by the doors.

“Lay a blessing upon your children, Mother!” Bulba told his wife. “Pray to God that they fight with valor, that they will always defend their knightly honor, and that they will always fight for the True Faith—for if they do not, it would be better for them not to walk the earth! Go to your mother, my sons: a mother’s prayer can save a man both on water and on land.”

Their weak and sobbing mother embraced them as only a mother can, and hung two small icons around their necks.

“May the Mother of God . . . protect you . . . and do not forget your own mother, my darling sons . . . send word to me that you are well. . . .” She was not able to speak further.

“Let’s go, my boys!” Bulba shouted.

The saddled horses stood in front of the door. Bulba jumped onto Devil, who suddenly veered to the side, feeling the twenty-pood load on his back, for Bulba was uncommonly stout and brawny.*

When the mother saw that her sons were already mounted, she rushed forward to the younger, whose features still retained a kind of tenderness. She grabbed the stirrup, and clung to his saddle with des-

* The pood is a Russian unit of weight equal to approximately thirty-six pounds.

peration in her eyes. Two burly Cossacks carefully pulled her away and carried her into the house. But as they rode out of the gate she came rushing out with the lightness of a wild goat, unimaginable at her age, held one of the horses with incomprehensible strength, and embraced her son with blind, crazed fervor. She was again carried into the house.

The young Cossacks rode off sadly, holding back their tears out of fear of their father, who was perturbed himself, although he struggled not to show it. It was a gray day. The green steppes glittered brightly. Birds chattered discordantly. After they had ridden awhile they looked back. It was as if their homestead had sunk into the steppes. All that could be seen above the grass were the two chimneys of their modest house and the tops of the trees, on the branches of which they had once climbed like squirrels. All they saw before them now, stretching out into the endless distance, was the steppe, calling to their minds the whole story of their lives, from the years when they had rolled about in the dew-wet grass to the years when they lay in wait for black-browed Cossack maidens who bolted over these steppes on fresh and nimble legs. Now only the pole above the well, with a cartwheel fastened to its top, jutted into the sky. Already the plain across which they had ridden seemed like a mountain that hides everything from view. Farewell to childhood, to games, to everything, everything!

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Autres éditions populaires du même titre

Résultats de recherche pour Taras Bulba

Taras Bulba (Modern Library Classics)

Vendeur : HPB-Diamond, Dallas, TX, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! N° de réf. du vendeur S_450346480

Acheter D'occasion

Expédition nationale : Etats-Unis

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Taras Bulba (Modern Library Classics)

Vendeur : HPB-Emerald, Dallas, TX, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! N° de réf. du vendeur S_460908846

Acheter D'occasion

Expédition nationale : Etats-Unis

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Taras Bulba (Modern Library Classics)

Vendeur : Your Online Bookstore, Houston, TX, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Good. N° de réf. du vendeur 0812971191-3-25481579

Acheter D'occasion

Expédition nationale : Etats-Unis

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Taras Bulba (Modern Library Classics)

Vendeur : HPB-Ruby, Dallas, TX, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! N° de réf. du vendeur S_465703073

Acheter D'occasion

Expédition nationale : Etats-Unis

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Taras Bulba

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. N° de réf. du vendeur G0812971191I3N00

Acheter D'occasion

Expédition nationale : Etats-Unis

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Taras Bulba

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Fair. No Jacket. Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. N° de réf. du vendeur G0812971191I5N00

Acheter D'occasion

Expédition nationale : Etats-Unis

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Taras Bulba

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, Etats-Unis

Paperback. Etat : Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. N° de réf. du vendeur G0812971191I3N10

Acheter D'occasion

Expédition nationale : Etats-Unis

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Taras Bulba (Modern Library Classics)

Vendeur : Book Alley, Pasadena, CA, Etats-Unis

paperback. Etat : Good. Good. Used with general wear and age toning to pages. Still in solid reading condition with no markings in text. N° de réf. du vendeur mon0000762136

Acheter D'occasion

Expédition nationale : Etats-Unis

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Taras Bulba (Modern Library Classics)

Vendeur : Textbooks_Source, Columbia, MO, Etats-Unis

paperback. Etat : Good. Ships in a BOX from Central Missouri! May not include working access code. Will not include dust jacket. Has used sticker(s) and some writing or highlighting. UPS shipping for most packages, (Priority Mail for AK/HI/APO/PO Boxes). N° de réf. du vendeur 000698149U

Acheter D'occasion

Expédition nationale : Etats-Unis

Quantité disponible : 2 disponible(s)

Taras Bul'ba

Vendeur : TextbookRush, Grandview Heights, OH, Etats-Unis

Etat : Good. All orders ship SAME or NEXT business day. Expedited shipments will be received in 1-5 business days within the United States. We proudly ship to APO/FPO addresses. 100% Satisfaction Guaranteed! N° de réf. du vendeur 52278172

Acheter D'occasion

Expédition nationale : Etats-Unis

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)