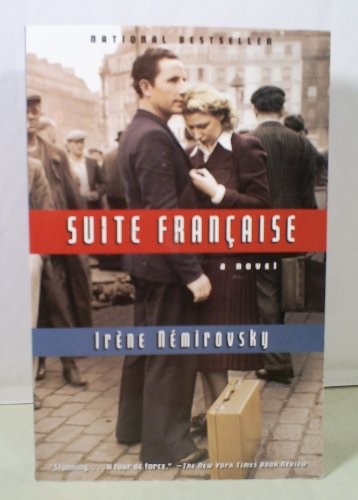

Articles liés à Suite Francaise

Synopsis

Unusual book

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Extrait

1War Hot, thought the Parisians. The warm air of spring. It was night, they were at war and there was an air raid. But dawn was near and the war far away. The first to hear the hum of the siren were those who couldn’t sleep—the ill and bedridden, mothers with sons at the front, women crying for the men they loved. To them it began as a long breath, like air being forced into a deep sigh. It wasn’t long before its wailing filled the sky. It came from afar, from beyond the horizon, slowly, almost lazily. Those still asleep dreamed of waves breaking over pebbles, a March storm whipping the woods, a herd of cows trampling the ground with their hooves, until finally sleep was shaken off and they struggled to open their eyes, murmuring, “Is it an air raid?”The women, more anxious, more alert, were already up, although some of them, after closing the windows and shutters, went back to bed. The night before—Monday, 3 June—bombs had fallen on Paris for the first time since the beginning of the war. Yet everyone remained calm. Even though the reports were terrible, no one believed them. No more so than if victory had been announced. “We don’t understand what’s happening,” people said.They had to dress their children by torchlight. Mothers lifted small, warm, heavy bodies into their arms: “Come on, don’t be afraid, don’t cry.” An air raid. All the lights were out, but beneath the clear, golden June sky, every house, every street was visible. As for the Seine, the river seemed to absorb even the faintest glimmers of light and reflect them back a hundred times brighter, like some multifaceted mirror. Badly blacked-out windows, glistening rooftops, the metal hinges of doors all shone in the water. There were a few red lights that stayed on longer than the others, no one knew why, and the Seine drew them in, capturing them and bouncing them playfully on its waves. From above, it could be seen flowing along, as white as a river of milk. It guided the enemy planes, some people thought. Others said that couldn’t be so. In truth, no one really knew anything. “I’m staying in bed,” sleepy voices murmured, “I’m not scared.” “All the same, it just takes one . . .” the more sensible replied.Through the windows that ran along the service stairs in new apartment blocks, little flashes of light could be seen descending: the people living on the sixth floor were fleeing the upper storeys; they held their torches in front of them, in spite of the regulations. “Do you think I want to fall on my face on the stairs! Are you coming, Emile?” Everyone instinctively lowered their voices as if the enemy’s eyes and ears were everywhere. One after another, doors slammed shut. In the poorer neighbourhoods there was always a crowd in the Métro, or the foul-smelling shelters. The wealthy simply went to sit with the concierge, straining to hear the shells bursting and the explosions that meant bombs were falling, their bodies as tense as frightened animals in dark woods as the hunter gets closer. Though the poor were just as afraid as the rich, and valued their lives just as much, they were more sheeplike: they needed one another, needed to link arms, to groan or laugh together.Day was breaking. A silvery blue light slid over the cobblestones, over the parapets along the quayside, over the towers of Notre-Dame. Bags of sand were piled halfway up all the important monuments, encircling Carpeaux’s dancers on the façade of the Opera House, silencing the Marseillaise on the Arc de Triomphe.Still at some distance, great guns were firing; they drew nearer, and every window shuddered in reply. In hot rooms with blacked-out windows, children were born, and their cries made the women forget the sound of sirens and war. To the dying, the barrage of gunfire seemed far away, without any meaning whatsoever, just one more element in that vague, menacing whisper that washes over those on the brink of death. Children slept peacefully, held tight against their mothers’ sides, their lips making sucking noises, like little lambs. Street sellers’ carts lay abandoned, full of fresh flowers.The sun came up, fiery red, in a cloudless sky. A shell was fired, now so close to Paris that from the top of every monument birds rose into the sky. Great black birds, rarely seen at other times, stretched out their pink-tinged wings. Beautiful fat pigeons cooed; swallows wheeled; sparrows hopped peacefully in the deserted streets. Along the Seine each poplar tree held a cluster of little brown birds who sang as loudly as they could. From deep beneath the ground came the muffled noise everyone had been waiting for, a sort of three-tone fanfare. The air raid was over.2 In the Péricand household they listened in shocked silence to the evening news on the radio, but no one passed comment on the latest developments. The Péricands were a cultivated family: their traditions, their way of thinking, their middle-class, Catholic background, their ties with the Church (their eldest son, Philippe Péricand, was a priest), all these things made them mistrustful of the government of France. On the other hand, Monsieur Péricand’s position as curator of one of the country’s national museums bound them to an administration that showered its faithful with honours and financial rewards.A cat held a little piece of bony fish tentatively between its sharp teeth. He was afraid to swallow it, but he couldn’t bring himself to spit it out either.Madame Péricand finally decided that only a male mind could explain with clarity such strange, serious events. Neither her husband nor her eldest son was at home: her husband was dining with friends, her son was not in Paris. Charlotte Péricand, who ruled the family’s daily life with an iron hand (whether it was managing the household, her children’s education or her husband’s career), was not in the habit of seeking anyone’s opinion. But this was of a different order. She needed a voice of authority to tell her what to believe. Once pointed in the right direction, there would be no stopping her. Even if given absolute proof she was mistaken, she would reply with a cold, condescending smile, “My father said so . . . My husband is very well-informed.” And she would make a dismissive little gesture with her gloved hand.She took pride in her husband’s position (she herself would have preferred a more domestic lifestyle, but following the example of our Dear Saviour, each of us has his cross to bear). She had come home between appointments to oversee her children’s studies, the baby’s bottles and the servants’ work, but she didn’t have time to take off her hat and coat. For as long as the Péricand children could remember, their mother was always ready to go out, armed with hat and white gloves. (Since she was thrifty, her mended gloves had the faint smell of stain remover, a reminder of their passage through the dry-cleaners.)As soon as she had come in this evening, she had gone to stand in front of the radio in the drawing room. Her clothes were black, her hat a divine little creation in fashion that season, decorated with three flowers and topped with a silk pom-pom. Beneath it, her face was pale and anguished, emphasising the marks of age and fatigue. She was forty-seven years old and had five children. You would have thought, to look at her, that God had intended her to be a redhead. Her skin was extremely delicate, lined by the passing years. Freckles were dotted over her strong, majestic nose. The expression in her green eyes was as sharp as a cat’s. At the last minute, however, it seemed that Providence had wavered, or decided that a shock of red hair would not be appropriate, neither to Madame Péricand’s irreproachable morals nor to her social status, so she had been given mousy brown hair, which she was losing by the handful since she’d had her last child. Monsieur Péricand was a man of great discipline: his religious scruples prohibited a number of pleasures and his concern for his reputation kept him away from places of ill repute. The youngest Péricand child was only two, and between Father Philippe and the baby, there were three other children, not counting the ones Madame Péricand discreetly referred to as the “three accidents”: babies she had carried almost to term before losing them, so that three times their mother had been on the verge of death.The drawing room, where the radio was now playing, was enormous and well-proportioned, with four windows overlooking the Boulevard Delessert. It was furnished in traditional style, with large armchairs and settees upholstered in golden yellow. Next to the balcony, the elder Monsieur Péricand sat in his wheelchair. He was an invalid whose advancing age meant that he sometimes lapsed back into childhood and only truly returned to his right mind when discussing his fortune, which was considerable (he was a Péricand-Maltête, heir of the Maltête family of Lyon). But the war, with its trials and tribulations, no longer affected him. He listened, indifferent, steadily nodding his beautiful silvery beard. The children stood in a semi-circle behind their mother, the youngest in his nanny’s arms. Nanny had three sons of her own at the front. She had brought the little boy downstairs to say goodnight to his family and took advantage of her brief entry into the drawing room to listen anxiously to what they were saying on the radio.The door was slightly ajar and Madame Péricand could sense the presence of the other servants outside. Madeleine, the maid, was so beside herself with worry that she came right up to the doorway. To Madame Péricand, such a breach of the normal rules seemed a frightening indication of things to come. It was in just this manner that the different social classes all ended up on the top deck during a shipwreck. But working-class people were highly strung. “How they do get carried away,” Madame Péricand thought reproachfully. She was one of those middle-class women who generally trust the lower classes. “They’re not so bad if you know how to deal with them,” she would say in the same condescending and slightly sad tone she used to talk of a caged animal. She was proud that she kept her servants for a long time. She insisted on looking after them when they were ill. When Madeleine had had a sore throat, Madame Péricand herself had prepared her gargle. Since she had no time to administer it during the day, she had waited until she got back from the theatre in the evening. Madeleine had woken up with a start and had only expressed her gratitude afterwards, and even then, rather coldly in Madame Péricand’s opinion. Well, that’s the lower classes for you, never satisfied, and the more you go out of your way to help them, the more ungrateful and moody they are. But Madame Péricand expected no reward except from God.She turned towards the shadowy figures in the hallway and said with great kindness, “You may come and listen to the news if you like.”“Thank you, Madame,” the servants murmured respectfully and slipped into the room on tiptoe.They all came in: Madeleine; Marie; Auguste, the valet and finally Maria, the cook, embarrassed because her hands smelled of fish. But the news was over. Now came the commentaries on the situation: “Serious, of course, but not alarming,” the speaker assured everyone. He spoke in a voice so full, so calm, so effortless, and used such a resonant tone each time he said the words “France,” “Homeland” and “Army,” that he instilled hope in the hearts of his listeners. He had a particular way of reading such communiqués as “The enemy is continuing relentless attacks on our positions but is encountering the most valiant resistance from our troops.” He said the first part of the sentence in a soft, ironic, scornful tone of voice, as if to imply, “At least that’s what they’d like us to think.” But in the second part he stressed each syllable, hammering home the adjective “valiant” and the words “our troops” with such confidence that people couldn’t help thinking, “Surely there’s no reason to worry so much!”Madame Péricand saw the questioning, hopeful stares directed towards her. “It doesn’t seem absolutely awful to me!” she said confidently. Not that she believed it; she just felt it was her duty to keep up morale.Maria and Madeleine let out a sigh.“You think so, Madame?”Hubert, the second-eldest son, a boy of seventeen with chubby pink cheeks, seemed the only one struck with despair and amazement. He dabbed nervously at his neck with a crumpled-up handkerchief and shouted in a voice that was so piercing it made him hoarse, “It isn’t possible! It isn’t possible that it’s come to this! But, Mummy, what has to happen before they call everyone up? Right away—every man between sixteen and sixty! That’s what they should do, don’t you think so, Mummy?”He ran into the study and came back with a large map, which he spread out on the table, frantically measuring the distances. “We’re finished, I’m telling you, finished, unless . . .”Hope was restored. “I see what they’re going to do,” he finally announced, with a big happy smile that revealed his white teeth. “I can see it very well. We’ll let them advance, advance, and then we’ll be waiting for them there and there, look, see, Mummy! Or even . . .”“Yes, yes,” said his mother. “Go and wash your hands now, and push back that bit of hair that keeps falling into your eyes. Just look at you.”Fury in his heart, Hubert folded up his map. Only Philippe took him seriously, only Philippe spoke to him as an equal. “How I hate this family,” he said to himself and kicked violently at his little brother’s toys as he left the drawing room. Bernard began to cry. “That’ll teach him about life,” Hubert thought.The nanny hurried to take Bernard and Jacqueline out of the room; the baby, Emmanuel, was already asleep over her shoulder. Holding Bernard’s hand, she strode through the door, crying for her three sons whom she imagined already dead, all of them. “Misery and misfortune, misery and misfortune!” she said quietly, over and over again, shaking her grey head. She continued muttering as she started running the bath and warmed the children’s pyjamas: “Misery and misfortune.” To her, those words embodied not only the political situation but, more particularly, her own life: working on the farm in her youth, her widowhood, her unpleasant daughters-in-law, living in other people’s houses since she was sixteen.Auguste, the valet, shuffled back into the kitchen. On his solemn face was an expression of great contempt that was aimed at many things.The energetic Madame Péricand went to her rooms and used the available fifteen minutes between the children’s bath time and dinner to listen to Jacqueline and Bernard recite their school lessons. Bright little voices rose up: “The earth is a sphere which sits on absolutely nothing.”Only the elder Monsieur Péricand and Albert the cat remained in the drawing room. It had been a lovely day. The evening light softly illuminated the thick chestnut trees; Albert, a small grey tomcat who belonged to the children, seemed ecstatic. He rolled around on his back on the carpet. He jumped up on to the mantelpiece, nibbled at the edge of a peony in a large midnight-blue vase, delicately pawed at a snapdragon etched into the bronze corner-mount of a console table, then in one leap perched on the old man’s wheelchair and miaowed in his ear. The elder Monsieur Péricand stretched a hand towards him; his hand was always freezing cold, purple and shaking. The cat was afraid and ran off. Dinner was about to be served. Auguste appeared and pushed the invalid into the dining room.They were just sitting down at the table when the mistress of the house stopped suddenly, Jacqueline’s spoon of tonic suspended in mid-air. “It’s your father, children,” she said as the key turned in the lock.It was indeed Monsieur Péricand, a short, stocky man with a gentle and slightly awkward manner. His normally well-fed, relaxed...

Revue de presse

“Extraordinary . . . A work of Proustian scope and delicacy, by turns funny and deeply moving, that captures a civilization in its most revealing moment: that of its undoing.”–Lev Grossman, Time“Stories about World War II seem to occur in black and white, all grainy and bleak. That makes the stunning novel Suite Française, about the German occupation of France, all the more remarkable. As the book opens and the Nazis approach the outskirts of Paris, the June skies are gorgeously bright; later, the narrative is rich with evocations of blossoms and trees heavy with fruit, of fragrant air and the sounds of birds–as well as a scene where a cat claws a bird to death and stabs its tiny heart. Lush beauty is the backdrop to dark events, and so is natural cruelty. The characters who populate this sweeping saga of violence and survival–and who exhibit far more self-interest than virtue–are described with the same gleaming precision. The author of Suite Française is one of the most fascinating literary figures you’ve never heard of–and her own tragic story only deepens the impact of her book . . . The [book’s] first part, ‘Storm in June,’ depicts in brilliant detail the tumultuous exodus from Paris in the summer of 1940 . . . There are harrowing scenes on the roads jammed with refugees . . . The second part, ‘Dolce,’ is quieter, if no less ominous. Set in an occupied village, it delineates the tangled emotions of the conquered and the conquerors . . . Suite Française–gripping, clear-eyed and lyrical–doesn’t seem incomplete. Yet as wonderful as it is, when you read Némirovsky’s notes, included in an appendix, you see the scope of her ambition and you mourn. She was planning a kind of "War and Peace" for the 20th century and, tragically, she never saw how her story could end.” –Cathleen McGuigan, Newsweek“Suite Française, written as Nazi tanks rolled across France, captures the chaos, fear, humiliation, and very occasionally, the courage of the French, as well as portraying the complex emotions that developed between occupier and occupied. The story behind this novel, and Némirovsky’s own fate, make for a heart-breaking coda.”–Kazuo Ishiguro, The Guardian“Compelling, gripping . . . A brilliant portrait of French society in 1940 . . . It rivals the story of Anne Frank’s diary, or the story of Albert Camus’s novel The First Man . . . Suite Française raises fascinating questions about what matters in the experience of reading: content or context. The context of Suite Française is endlessly fascinating. Then there is the novel itself[:] a society novel [but] a great one, in the devastating tradition of Edith Wharton . . . [Némirovsky wrote] with supreme lucidity [and] expressed with great emotional precision her understanding of the country that betrayed her.”–Alice Kaplan, The Nation“What is so remarkable about Suite Française, apart from its artistic merit, is that it survived at all and has, at last, become available for us to read . . . [It] is an extraordinary work, an astonishing blend of fiction and fact, history and storytelling.”–Earl L. Dachslager, Houston Chronicle“Extraordinary, visceral, photo-sharp . . . Sometimes a book can throw wide open a door that has stood barely ajar for decades. [Suite Française] is one such book for me. [It] bears eloquent, complex testimony to a time and place that, for those who didn’t live through it, defies easy understanding . . . Uncannily perceptive, astonishing.”–Michael Upchurch, Seattle Times“Transcendent, astonishing . . . Suite Française, which might be the last great fiction of the war, provides us with an intimate recounting of occupation, exodus and loss. [Its] staggering power is that it affirms the idea that art can offer a path to salvation . . . This might be the most moving novel I will ever read . . . Like Anne Frank, Irène Némirovsky was unaware of neither her circumstance nor the growing probability that she might not survive. And still, she writes to us.”–Sharon Dilworth, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette“Beautifully restrained . . . [Némirovsky’s] talent was quite considerable and her personal story rather moving and tragic . . . I don’t know of a more striking recent case where biography and artistic accomplishment are so intertwined . . . Némirovsky left behind [a note] about how to compose the projected later volumes of this novel project: ‘The most important and most interesting thing here is the following: the historical, revolutionary facts etc. must be only lightly touched upon, while daily life, the emotional life . . . must be described in detail.’ This she did rather splendidly in the first two books.”–Alan Cheuse, NPR “[Suite Française is] clearly the work of a novelist with an alert eye for self-deceit, a tender regard for the natural world, and a forlorn gift for describing the crumbling, sliding descent of an entire society into catastrophic disorder. There are many sustained scenes and sharply caught moments that no subsequent rewriting (had the author been given the opportunity) could have improved on.”–Dan Jacobson, London Review of Books“This is possibly the most devastating indictment of French manners and morals since Madame Bovary, as hypnotic as Proust at the biscuit tin, as gruelling as Genet on the prowl. Irène Némirovsky is, on this evidence, a novelist of the very first order, perceptive to a fault and sly in her emotional restraint.”–Norman Lebrecht, The Evening Standard“The history of the manuscript, and its survival, is remarkable enough. The authority of the novel, though, does not come from its history, but from its quality . . . The narrative is eloquent and glowing with life. Its tone reflects a deep understanding of human behaviour under pressure and a hard-won, often ironic composure in the face of violation . . . Even in its incomplete form Suite Française is one of those rare books that demands to be read.”–Helen Dunmore, The Guardian“Suite Française clutches the heart, its warmth and intensity give as much pleasure as a work of overpowering genius.”--Carmen Callil, The Times (London)“Against the odds, Suite Française has survived. It does so as a triumph of indomitability and a masterwork of literary accomplishment.”–The Sunday Times“A magnificent work that its readers will cherish for as long as they still care about the art of fiction or the history of Europe. Even more astonishing, given its heroically large themes and the desperate circumstances of its composition, this is no gloomy elegy but a scintillating panorama of a people in crisis--witty, satirical, romantic, waspish and gorgeously lyrical by turns. Every page shines both with a ravishing delight in the surfaces of life, and a profound empathy for the souls of its characters, that raises it to the rank of the Russian and French masters.”–The Independent“Celebrated in pre-WWII France for her bestselling fiction, the Jewish Russian-born Némirovsky was shipped to Auschwitz in the summer of 1942, months after this long-lost masterwork was composed . . . In a workbook entry penned just weeks before her arrest, Némirovsky noted that her goal was to describe ‘daily life, the emotional life and especially the comedy it provides.’ This heroic work does just that, by focusing–with compassion and clarity–on individual human dramas.”–Publishers Weekly (starred review)“A grandly symphonic, courageous, and scathing work . . . Suite Française is a magnificent novel of the insidious devastation of occupation, and Némirovsky is brilliant and heroic, summoning up profound empathy for all, including regretful German soldiers. Everything about this transcendent novel is miraculous.”–Booklist (starred review)“A valuable window into the past, and the human psyche. This is important work.”–Kirkus (starred review)“Astonishing . . . Suite Française is a surprising, transfixing book.”–Financial Times“Stunning . . . A tour de force of narrative distillation, using a handful of people to represent a multitude. Némirovsky’s shifts in tone and pace, sensitively rendered in Sandra Smith’s graceful translation, are mesmerizing . . . She wrote what may be the first work of fiction about what we now call World War II. She also wrote, for all to read at last, some of the greatest, most humane and inclusive fiction that conflict has produced.”--The New York Times Book Review “It is not possible, nor would it make sense, to read Némirovsky’s unfinished novel apart from the circumstances of its writing. What if Tolstoy had been alive and had sat down to write among the cannonades of Borodino, instead of 50 years later? This is one thing. Another is the terribly moving disjunction between the catastrophe that was overtaking France and (more shamefully) Némirovsky and her spacious testimony. Further, there is the prescience with which victim as dispassionate observer--or observer as dispassionate victim--gave voice to the consequences that would follow . . . There is nothing sentimental or tragic here; reality is what she’s after. As she is, also, in the splendid vignettes of townspeople and soldiers . . . In light of what happened to Némirovsky, her vision is remakable. She did indeed draw on some of what she had seen in the early days of her village’s occupation, before a more terrible regime moved in . . . What did come we know in hindsight. Némirovsky knew it in tragic foresight.”–The New York Times“Némirovsky’s scope is like that of Tolstoy: She sees the fullness of humanity and its tenuous arrangements and manages to put them together with a tone that is affectionate, patient, and relentlessly honest . . . What leaves you breathless is the sense that you have in your hands something important, something precious and rare: a lost masterpiece. It is a privilege to read this book.”–O: The Oprah Magazine“The story behind Irène Némirovsky’s Suite Française is painful and extraordinary, a story yearning to be told . . . It would be a remarkable novel had it been written only recently, in comfortable circumstances; given its provenance, and its history, it is a book that demands to be read.”–Claire Messud, Bookforum“Extraordinary . . . It has a sense of immediacy unexpected in a novel about a war that took place more than half a century ago.”–Amy Woods Butler, St. Louis Post-Dispatch“Superb . . . This extraordinary work of fiction about the German occupation of France is embedded in a real story as gripping and complex as the invented one . . . It is hard to imagine a reader who will not be wholly engrossed and moved by this book . . . Némirovsky achieve[s] her penetrating insights with Flaubertian objectivity. She gives us startling, steely etched sketches of both collaboration and resistance among people motivated by personal loyalties and grievances that date from before the war . . . This is an incomparable book, in some ways sui generis. While diaries give us a day-to-day record, their very inclusiveness can lead to tedium; memoirs, on the other hand, written at a later date, search for highlights and illuminate the past from the vantage point of the present. In Némirovsky's Suite Française we have the perfect mixture: a gifted novelist’s account of a foreign occupation, written while it was taking place, with history and imagination jointly evoking a bitter time, correcting and enriching our memory.”–Ruth Kluger, The Washington Post Book World

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Gratuit expédition vers Etats-Unis

Destinations, frais et délaisAcheter neuf

Afficher cet articleGratuit expédition vers Etats-Unis

Destinations, frais et délaisRésultats de recherche pour Suite Francaise

Suite Fran?aise

Vendeur : World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, Etats-Unis

Etat : Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. N° de réf. du vendeur 00045634424

Quantité disponible : Plus de 20 disponibles

Suite Fran?aise

Vendeur : World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, Etats-Unis

Etat : Acceptable. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. N° de réf. du vendeur 00054784326

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Suite Française

Vendeur : Gulf Coast Books, Cypress, TX, Etats-Unis

Hardcover. Etat : Good. N° de réf. du vendeur 1400044731-3-20989511

Quantité disponible : 2 disponible(s)

Suite Française

Vendeur : Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, Etats-Unis

Hardcover. Etat : Good. N° de réf. du vendeur 1400044731-3-24237510

Quantité disponible : 2 disponible(s)

Suite Française

Vendeur : Zoom Books Company, Lynden, WA, Etats-Unis

Etat : very_good. Book is in very good condition and may include minimal underlining highlighting. The book can also include "From the library of" labels. May not contain miscellaneous items toys, dvds, etc. . We offer 100% money back guarantee and 24 7 customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur ZBV.1400044731.VG

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Suite Franaise

Vendeur : Used Book Company, Egg Harbor Township, NJ, Etats-Unis

Etat : VeryGood. Shows minimal signs of wear and previous use. Can include minimal notes/highlighting. A portion of your purchase benefits nonprofits! - Note: Edition format may differ from what is shown in stock photo item details. May not include supplementary material (toys, access code, dvds, etc). N° de réf. du vendeur 584ZSU000LYN_ns

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Suite Française

Vendeur : Books for Life, LAUREL, MD, Etats-Unis

Etat : good. Book is in good condition. Minimal signs of wear. It May have markings or highlights, but kept to only a few pages. May not come with supplemental materials if applicable. N° de réf. du vendeur LFM.5WX1

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Suite Fran'aise

Vendeur : More Than Words, Waltham, MA, Etats-Unis

Etat : Very Good. . . All orders guaranteed and ship within 24 hours. Before placing your order for please contact us for confirmation on the book's binding. Check out our other listings to add to your order for discounted shipping. N° de réf. du vendeur BOS-I-09g-01471

Quantité disponible : 2 disponible(s)

Suite Fran'aise

Vendeur : More Than Words, Waltham, MA, Etats-Unis

Etat : Good. . . All orders guaranteed and ship within 24 hours. Before placing your order for please contact us for confirmation on the book's binding. Check out our other listings to add to your order for discounted shipping. N° de réf. du vendeur BOS-L-08g-01626

Quantité disponible : 8 disponible(s)

Suite Française

Vendeur : Seattle Goodwill, Seattle, WA, Etats-Unis

hardcover. Etat : Acceptable. N° de réf. du vendeur mon0000033720

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)