Articles liés à India: In Word and Image, Revised, Expanded and Updated:...

Synopsis

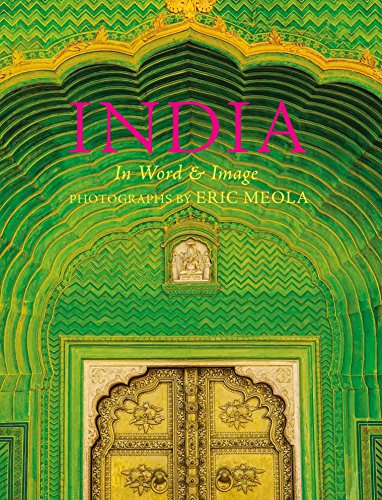

Gorgeously jaw-dropping, India has been beautifully redesigned with 32 additional pages of glorious photos shot by Eric Meola since India was first published.

This revised and expanded version of Eric Meola's 2008 India takes the reader on a journey through Mumbai, Rajasthan, Agra, Dungarpur, along desert roads, to the Ganges water's edge, including spectacular ruins, the Taj Mahal, and the Festival of Elephants, capturing the spectacle and vibrant colors of these ancient regions.

INDIA is rapidly becoming one of the pre-eminent leaders of the twenty-first century. For more than a decade, Eric Meola has returned repeatedly to India, photographing the people, temples, landscapes, architecture, celebrations, and art of this uniquely exuberant and incredibly diverse country. Meola's journeys took him from the Himalayas and monasteries in the North to the temples of Tamil Nadu in the South, from the color and pageantry of Rajasthan in the West to the tea plantations of Darjeeling in the East. Over 200 photographs (edited from more than 25,000 images) will fill this beautifully printed, large-format book. The photographs will be accompanied by dozens of essays, stories, and poems by contemporary and classical Indian writers.

Table of Contents

INDIA: In Word & Image

Photographs by Eric Meola

Contents

19 Eric Meola

My Private India

24 Bharati Mukherjee

Introduction

29 Salman Rushdie

Midnight’s Children

34 I. Allan Sealy

The Trotter-Nama

47 R. K. Narayan

Ganga’s Story

52 R. K. Narayan

The Ramayana

63 William Buck

Mahabharata

67 R. K. Narayan

Mr. Sampath—The Printer of Malgudi

71 Gita Mehta

A River Sutra

83 Kiran Desai

The Inheritance of Loss

86 Manil Suri

The Death of Vishnu

94 R. K. Narayan

The Guide

100 Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

The Housewife

110 Jhumpa Lahiri

Interpreter of Maladies

119 Thomas Byrom

Dhammapada

120 Anita Desai

Fasting, Feasting

129 Amit Chaudhuri

A Strange and Sublime Address

132 Nirad C. Chaudhuri

My Birthplace

136 R. K. Narayan

The Dark Room

147 Nirad C. Chaudhuri

My Birthplace

150 Kiran Desai

Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard

163 Salman Rushdie

Midnight’s Children

169 Clark Blaise and Bharati Mukherjee

Days and Nights in Calcutta

178 Rabindranath Tagore

Subha

182 Upamanyu Chatterjee

English, August

185 Vikram Seth

A Suitable Boy

190 Amit Chaudhuri

A Strange and Sublime Address

194 Arundhati Roy

The God of Small Things

198 Anita Desai

Fasting, Feasting

203 O. V. Vijayan

The River

211 Kamala Markandaya

Nectar in a Sieve

214 Amit Chaudhuri

Sandeep’s Visit

222 Gita Mehta

A River Sutra

232 V. S. Naipaul

An Area of Darkness

239 Manil Suri

The Death of Vishnu

243 Ismat Chughtai

The Wedding Shroud

246 Nirad C. Chaudhuri

The Autobiography of an Unknown Indian

250 Nirad C. Chaudhuri

My Birthplace

254 Anita Desai

A Devoted Son

260 Kamala Markandaya

Nectar in a Sieve

---

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

À propos de l?auteur

Eric Meola’s graphic use of color has informed his photographs for more than four decades. In 2004, Graphis Editions published his first book The Last Places on Earth. An exhibition in England of his photographs of Bruce Springsteen, which coincided with the publication of his second book Born to Run: The Unseen Photos (Insight Editions, 2006), was followed in 2008 by the first edition of INDIA: In Word & Image (Welcome Books, NY), and an exhibit in 2009 at the Art Directors Club of New York. In 2011, Ormond Yard Press of London published his most unusual book, an oversize (18"x24", 14 lbs.) edition of photographs of Bruce Springsteen—Born to Run Revisted—that was limited to 500 copies. Streets of Fire, his fifth book, was published by HarperCollins in September of 2012. Winner of numerous awards, with prints in several private collections and museums, including the National Portrait Gallery, he is a Canon “Explorer of Light”.

Introduction Author

Bharati Mukherjee, award-winning author and professor of English at the University of California, Berkeley, is well known both as a writer of fiction and as a social commentator. Her most recent novel is The Tree Bride, the second novel in a trilogy that bridges modern America and historical India. Her other novels include Jasmine, Leave It to Me, Desirable Daughters, and The Holder of the World. Her short stories are found in The Middleman and Other Stories, and Darkness.

Extrait. © Reproduit sur autorisation. Tous droits réservés.

from India: In Word and Image

Photographs by Eric Meola

1 Flap copy

2 Back cover quote

3 Foreword by Eric Meola

4 Introduction by Bharati Mukherjee

5 "Mahabharata" by William Buck

6 “Fasting, Feasting” by Anita Desai

---

1 Back cover quotes

“[An] exotic five-star vacation in itself. The portraits, landscapes, and photographic studies of flora and architecture are more art than documentary, and are accompanied not by history lessons, but by masterly literary prose…Such words can hold their own with any pictures, even Meola’s glorious photographs.” — Amy Finnerty, New York Times Book Review

“Eric Meola has captured a brilliant portrait of a vast and vibrant India through his artistic mastery of his lens. In a nation where city life resembles any urban metropolis globally, he has captured the unaltered richness of ancient India juxtaposed between thousands of years of its traditional civilization.” — Vishaka Hussain Pathak, US India Business Council

“Within pages I was mesmerized by the changing contrasts in hues, textures, and compositions of this visual odyssey. This work is mostly about India’s onslaught on the senses” — David Braun, National Geographic News Watch

---

2 Flap copy

India: a kingdom of color where every turn dazzles more than the turn before. Where every nuance speaks of pageantry and celebration, of gods within gods, of maharajahs and past glory, of a sense of life and wonder unlike any other place on earth. For more than a decade, Eric Meola has returned repeatedly to India, photographing the people, landscapes, architecture, celebrations, and art of this uniquely exuberant and incredibly diverse country. Meola’s journeys took him from the Himalayas and monasteries in the North to the temples of Tamil Nadu in the South, from the color and pageantry of Rajasthan in the West to the tea plantations of Darjeeling in the East. More than 200 photographs fill this stunning, ambitious book. Camels in the dust at the Pushkar fair; a young boy crossing the Yamuna river on the back of a water buffalo; the spectacular celebration of Holi near Mathura; a lone gypsy in the stark desert near Jaipur. . .each and every one of Meola’s images is a work of art that speaks of India’s myriad colors and wonders. This visual celebration is accompanied with words from major writers whose works derive inspiration from Indian themes. Salman Rushdie speaks of a mythical land with a new dream; Anita Desai gives life to relationships; R. K. Narayan shares the legends of India; Jhumpa Lahiri explores the possibility of love among ancient ruins. More than 30 literary passages capture and immerse readers in the compelling story that is India. INDIA: In Word & Image captures and reveals this mysterious and dazzling country.

---

3 Foreword by Eric Meola

October 2007

I am in an air-conditioned car somewhere in the streets of Kolkata, scrolling through the names on my cell phone: Pankaj, Deepak, Namas, Saritha, Venkat, Narendra, Mahesh. . . I ask the driver to turn off the cold air as my lenses will fog as soon as I jump out, which might be at any moment now.

The summer heat has wrapped itself around us, but inside the car there is only the ubiquitous, incessant sound of honking horns. I watch through the window as men in the street sell fruit, candy, pots, tires, rope . . . all manner of things. A woman walks by breastfeeding her baby. A man, completely naked, walks by in the opposite direction.

What seems like a thousand thousand cars are simmering in the heat, packed within fractions of an inch of one another. Bicyclists weave in and out of the interstices of space between. A man approaches a porter carrying a huge container of water strapped to his back; lifting a bowl to his mouth he drinks, then dips again, and lifting the bowl far above his head he empties a waterfall over his body. Another man is kneeling nearby, welding a car’s axle. Yet another is squatting at the street’s edge repairing shoes, the tools of his trade scattered in dull scraps at his feet.

Dogs, cattle, goats, monkeys, cats, and children scurry through the traffic-choked streets. A man sleeps on his back in a cart. A donkey falls asleep while standing up. In ultraslow motion we drift by a spotless polished Rolls Royce sitting on a rotating pedestal in a showroom. Billboards for Gucci and Prada hang above a man sitting on the pavement, legs crossed, eyes closed. . .motionless. There are no two-way or one-way streets. There are only Everyway streets—left, right, forward, and back. And around and around.

A woman knocks on our window, begging. Just beyond her a bus driver is counting money, the bills crisply folded between fingers of a closed hand while the fingers of the other hand leaf through tightly packed 10-rupee notes.

Suddenly I remark to my guide about this seemingly infinite chaos, which somehow seems choreographed by some unknown force. In its own way, the way of India, there is an order to this world I see spinning out of control. Nowhere is anyone quarreling, nowhere does anyone seem unhappy. A bit impatient perhaps. The honking horns fill my ears again. My ears pick up the incongruous ring of an old thumb-operated bell on a bicycle’s handlebars . . .and then a calliope, its high-pitched notes a perfect metaphor for the circus in front of me.

I comment to my guide about how thunderstruck I am that everything seems to keep going, that somehow, despite a million people moving in opposite directions, despite an overwhelming sense of “it” not working, everyone will get to where they are going. He breaks into a grin and says, “Well, your country gave us that, you know!”

Seeing my puzzled look he continues: “Your great writer from America, Thoreau. He taught us this, this sense of acceptance, this inner peace, this patience with life.” It is not the first time I have been lectured about Thoreau by an Indian. Once, in a small village in the Rann of Kutch, a man came out of a doorway bent over from the blinding sun, which beat down mercilessly. He walked a few steps, then turned and asked me about Thoreau and told me how much Thoreau’s writings meant to him. And to Gandhi.

Suddenly I am wrenched back to the present—the driver is beginning to make a U-turn! He not only has the audacity to consider it, but somehow in this sea of metal on metal he accomplishes the impossible.

January 2007

. . .Seven and a half hours to Paris, two hours on the ground, another seven and a half hours to Mumbai, a delayed flight, and five hours in a dreary, dark lounge before going on another two hours to Delhi. Two hours for the luggage to come off the plane, and three waiting in line to report my check-in luggage had been lost. On to customs and the rep from the tourist board. But customs agent Singh has something different in mind, and I am soon in the midst of the abyss of Indian bureaucracy. I watch as my camera pack is taken into a labyrinthine room and locked away. Three days later my luggage is found and the equipment released. Then a 14-hour night drive to Allahabad to see the Kumbh Mela, the blinding light of oncoming headlights erasing my body’s need to collapse in exhaustion. The next day I am wedged in a mass of human flesh locked so tight that all movment is suspended by a simple law of physics: 10 million people cannot occupy the same space at the same time.

A few days later in Varanasi I watch as five women walk down the steps of the Sankatha ghat and with reverence place a diya at the water’s edge. It floats out to me. I can feel my body’s resistance give in to the week’s endurance marathon. . . the sun is out now and all the colors are electric. An old man walks to the water’s edge and pours water from a small copper pitcher into the Ganges. Life on the river is in ebb and flow. . . .Suddenly my thoughts are interrupted by my guide’s voice. “You take many, many ‘snaps,’ so many, many ‘snaps.’”

. . .Amritsar, or the “pool of nectar,” is the center of the Sikh religion; in the midst of a huge pool surrounded by water sits the Golden Temple, and for two days it’s been obscured by fog. My train back to Delhi is a few minutes late that morning, so I rush to the temple and at last catch the glint of brilliant gold leaf reflected in the pool. On the long train ride back to Delhi, a Sikh sits next to me and we talk the entire eight hours, discussing Sikh history, politics, Kashmir, Punjab, the war in Iraq and his life in Canada. He’s a truck driver and lives in British Columbia, and he keeps me entertained with his stories of working for Wal-Mart and his encounters with redneck truckers in Los Angeles.

February 2007

At last, sand. The desert . . . the road to Jaisalmer . . .fifteen degrees warmer here. Alone on the road, no constant honking of horns. A new driver, “Vinay.” We share a bag of cashews. No matter what I say he smiles and says yes. “Great weather today, Vinay.” “Yes.” “Uh, the car has five flat tires.” “Yes.” But Vinay has an uncanny ability to know what I want to shoot, and in the two hours before sunset on the road from Jodhpur to Jaisalmer, Vinay helps me make half a dozen roadside portraits and it’s as if he’s cheering me on, “. . .Yes, yes, YES.”

Jaisalmer sits on the western edge of Rajasthan, near the sand dunes of the Thar desert and near the border with Pakistan. The ramparts of the old fortress sit on a small mesa of crumbling sand, rising in a dusty pink mirage above the surrounding clay houses.

There is the sense of past glory, with entryways guarded by massive rusting iron doors. Long-forgotten empires are everywhere in this kingdom of color, in this nation obsessed with infinite detail and ambition and hope; each turn bedazzles more than the turn before, each nuance speaks of pageantry and celebration, of gods within gods, of maharajahs, of a sense of life and wonder unlike any other place on earth.

We are on the road—the rutted, dusty roads of an India exploding into the modern world. “She” appears from nowhere, patiently moving through a field of tall winter wheat, her backlit yellow sari unfurling in the sun, her arms outstretched, using a hand scythe to cut out weeds. I have Vinay pull over, and because I want to shoot from a somewhat higher angle I sit on top of the car on the luggage platform as traffic hurtles by. I had tried shooting a scene like this several days before, but this time the backlight is perfect, and although she is very much aware of me, I am able to shoot for several minutes before deciding my luck might run out with the traffic as the trucks are dodging cattle wandering on the highway.

A few days later Vinay and I are on the road again at 6:45 a.m. on a five-hour drive to Jodhpur from Deogarh. Twenty minutes after we start we pass a low stone wall in a field, with several peacocks walking along it toward an arched canopy on one end. I have Vinay maneuvering the car as the sun is about to rise over the Aravelli hills, when one of the peacocks abruptly jumps up on the dome. Just then a truck comes down the otherwise deserted road . . . and the peacock flies off. I change lenses, look up. . .the peacock has returned. I manage to get two shots before it jumps down again. Another auspicious beginning to another auspicious day—a peacock, the national bird of India!

The next day I am at my favorite place in India, the Juna Mahal, the fading 13th-century “old palace” of Dungarpur—almost as old as the town itself. lt is one of the lesser-known treasures of India, and I spend an entire quiet, glorious afternoon photographing the crumbling interior without being disturbed. The only other person there is an Englishwoman who sits on the floor of a nave, pastels and watercolors spread around her, patiently drawing the myriad

details of inlaid tiles, mirrors, and colored glass. Each room is a phantasmagoria of a bygone era; hidden behind a small pair of nondescript wooden doors is a series of detailed paintings from the Kama Sutra.

November 2007

It has been just 10 years since my first trip to India. The population has now swelled to 1.2 billion people—300 million more than there were in 1998. One of every six people on the earth is Indian. In 10 years the population has increased by more than the entire population of the United States, and it took the States more than 200 years to reach that number.

I have been trying for more than a year to get permission to photograph Durbar Hall, at the Amba Vilas Palace in Mysore. At first the minister of Tourism and Culture told me that I have to get permission from the maharajah of Mysore. The maharajah then told me I would have to go to the chief minister of the State of Karnataka, but as I am not a native of India I would need to seek permission from the Department of Internal Affairs in Delhi, which I did. But they have sent me back to the chief minister.

I have for now given up all hope of photographing Durbar Hall and am now simply seeking permission to use my tripod in the great caves at Ellora and Ajanta.

Late one afternoon, my driver takes me to the nondescript offices in New Delhi of the Archaeological Survey of India. In a room that could have been constructed by David Lean at Shepperton Studios near London, men scurry about, each clutching sheaves of paperwork, each holding his agenda like a baby pressed to his chest, each wide-eyed in a nervous quest to push to the front of the line. I am at some point given a few sheets of hand-lined white paper and told to write an essay about who I am and what it is I want.

The object of all the attention in the room seems to be a man that Charles Dickens would have called a “scrivener,” or clerk, or in this case the secretary to the secretary. This courtly old gentleman’s glasses have slid precipitously to the very end of his nose, and one can only guess at what holds them there. A man pushes to the front of the line and with a gasp of relief drops what seems like three New York phone directories’ worth of paperwork onto this man’s desk. Strangely, the clerk does not look up but almost immediately proceeds to make notes. He pulls back 30 or 40 pages, immediately scans the entire page he has miraculously come to and with an almost imperceptible movement crosses out a word or two. Then he’s on to the next invisible divider 20 or 30 pages later, and again, with a sharp clucking of his tongue, crosses out a word. All the while his body arcs forward as if his waist is a ball joint and his nose the beak of a bird, pecking out the words. Peck, peck. . . peck, peck, peck. In less than two minutes he has completely edited to his satisfaction what I guess is a 1,200-page document.

I complete my essay about who I am and what I want to photograph and the secretary to the secretary reviews it, makes a few notes and asks me to wait for the chief secretary, who will append his signature. I wait another two hours, my eyes glazing over, and then the clerk motions to me that my papers are now officially approved. As I am about to leave he begins listing, in a long, monotonous drone, a series of caveats. “You do understand, Sri Eric, that when you reach the State of Maharashtra, you will need to stop at the local office of the Archaeological Survey and fill out additional forms as each office has their own rules for granting permission . . . ”

I walk out into the air and take a deep breath. I smile a small smile. In front of me rotting ancient file cabinets in a long row lean precariously, as if a mynah bird’s weight would topple them in an instant. Papers bulge from every seam. It begins to rain a soft, cooling rain.

* * *

Since my first trip to India, there have been so many changes, the changes that come with wealth and power and TV and cars and the modern world. I see rich and poor, but what I see more than anything else is an entire nation embracing life. Every day there is a celebration, if not dozens, throughout the country, for that is what India is about—a continuous celebration of life and its mysteries.

The light here is like no other place on earth, filtered by the dust of millions on the move, on fire with a sun that seems suspended in time and place. I love to wake before dawn and walk down to the ghats and watch the day, and the people, and India, come alive as the sun rakes across the Ganges.

As a photographer, I am drawn to India because of the psychedelic colors that seem to permeate every facet of life. I go there for all the contradictions of a place that is like no other I have been to; I am drawn to India because the people are blessed with childhood’s sense of wonder, which they have never lost.

I was startled one day to realize that what I had seen as infinite chaos was, in fact, infinitely ordered, and in that simple truth I found the soul of India. A sadhu faced the rising sun. A young boy crossed the Yamuna river on the back of a water buffalo. A mother’s hands gently cupped the face of her daughter. India is caught in the throes of change. But there will forever be a corner of the world that is my private India, the India in my eyes and of my heart.

---

4 Introduction by Bharati Mukherjee

I am a city girl, Kolkata born, Kolkata raised. I see my surroundings in muted urban colors. The Kolkata of my childhood was a subtropical metropolis with a crumbling infrastructure. In fact—shameful as it may sound—urban middle-class children of my generation deliberately insulated themselves from street and rural India. They learned to close their eyes. My neighborhood was my entire universe, and in art classes in grade school I painted it in the sooty grays of cow-dung-fueled cooking fires, the grainy tans of summer dust, the muddy greens of monsoon-churned lawns, the brackish blue of flooded streets, the sludgy browns of open sewers. Few neighbors owned cameras. When a young woman was considered ready to be launched into the matrimonial market, she was led into a photographer’s studio and posed to look shyly desirable in front of props that included potted plants and peacock feathers.

In the winter of 1948, my father splurged on a secondhand camera. All snapshots from the late 1940s and through the 1950s in our family album are in fuzzy focus, black leeching into white, the corners yellow from an excess of glue. All are of groups of relatives staring earnestly at the lens. Film was too expensive to waste on landscape, strangers, or “compositions.” The only photos of individual faces were of departed elders, isolated from the group photos and then enlarged, framed, garlanded, and paid homage to every evening with incense and prayers.

Growing up, I had little awareness of photojournalism and no experience of photography as art. The only images of Kolkata that I chanced upon in library books were reproductions of Samuel Bourne’s and Henri Cartier- Bresson’s black-and-white photographs. Bourne had lived in my hometown from 1863 to 1869, when the subcontinent was under British rule; Cartier-Bresson had visited India for the first time in 1947, commissioned to record the newborn nation’s celebration of independence. The India of these two European professional photographers was simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar, each distinct from the other.

In Bourne’s images I saw my universe distilled into colonial iconography. Cartier-Bresson’s gravely humanistic images of post-Partition, post-independence refugees caught the wit and grace in the anonymous throngs of violently displaced, newly beggared men, women, and children who lived and slept on the sidewalk outside our house. What the well-housed urban-dwellers saw as chaos on the streets, photography showed as emergencyresponse choreography.

Even the willfully unobservant child can learn to open her eyes. For me, it began with the discovery of Mughal miniature paintings, with their vibrant colors and dense, inspired narratives. Later came moonless desert night skies and countless pin-sharp stars and cloudy galaxies—how could we not be persuaded by the myths they spawned?— and then at least one Eric Meola moment. In the mid- 1970s, on a winter drive through the desert of western Rajasthan, our car came upon miles of saris drying on the concrete. As we approached (probably the first vehicle in an hour), word went out and the washerwomen arose magically from the dunes to pull the saris aside.

Eric Meola’s India is at once contemporary and timeless. He uncovers the beauty (and the ballet) of survival embedded in the daily lives of ordinary citizens: a boy bathing his family’s water buffalo, a man hanging up the day’s laundry, wives toting tiffin carriers of food to husbands tilling fields; worshippers floating votive clay lamps in holy river water, a child being hugged by her mother, adults smearing each other with brilliantly hued powders during the annual spring “holi” festival, vendors hawking jasmine wreaths and marigold petals; an elephant painted to look like a tiger, lizards crawling up stone limbs of deities carved into temple walls.

The joy he takes in discovering his “private India” is infectious. Eric’s vision embraces India’s excess of color, complexity, and self-confidence, and I long for him to bring his all-discovering eye to my hometown and to the spectacular new cities of India, to find the vivid colors and subtle order we inattentive urban-dwellers missed the first time around.

---

5 Mahabharata by William Buck

Listen— I was born fullgrown from the dew of my mother’s body. We were alone, and Devi told me, “Guard the door. Let no one enter, because I’m going to take a bath.”

Then Shiva, whom I had never seen, came home. I would not let him into his own house.

“Who are you to stop me?” he raged.

And I told him, “No beggars here, so go away!”

“I may be half naked,” he answered, “but all the world is mine, though I care not for it.”

“Then go drag about your world, but not Parvati’s mountain home! I am Shiva’s son and guard this door for her with my life!”

“Well,” he said, “you are a great liar. Do you think I don’t know my own sons?”

“Foolishness!” I said. “I was only born today, but I know a rag picker when I see one. Now get on your way.”

He fixed his eyes on me and very calmly asked, “Will you let me in?”

“Ask no more!” I said.

“Then I shall not,” he replied, and with a sharp glance he cut off my head and threw it far away, beyond the Himalayas.

---

6 “Fasting, Feasting” by Anita Desai

Curling up on the mat, around Mira-masi’s comfortable lap, one hand on her thumping, wagging knee, Uma would listen to her relate those ancient myths of Hinduism that she made sound as alive and vivid as the latest gossip about the family. To Mira-masi the gods and goddesses she spoke of, whose tales she told, were her family, no matter what Mama might think—Uma could see that.

She never tired of hearing the stories of the games and tricks Lord Krishna played as a child and a cowherd on the banks of the Jumna, or of the poet-saint Mira who was married to a raja and refused to consider him her husband because she believed she was already married to Lord Krishna and wandered through the land singing songs in his praise and was considered a madwoman till the raja himself acknowledged her piety and became her devotee. Best of all was the story of Raja Harishchandra who gave up his wealth, his kingdom and even his wife to prove his devotion to the god Indra and was reduced to the state of tending cremation fires for a living; his own wife was brought to him for her cremation when at last the god took pity on him and restored her to life. Then Uma, with her ears and even her fingertips tingling, felt that here was someone who could pierce through the dreary outer world to an inner world, tantalizing in its color and romance. If only it could replace this, Uma thought hungrily.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurWelcome Books

- Date d'édition2013

- ISBN 10 1599621282

- ISBN 13 9781599621289

- ReliureRelié

- Langueanglais

- Numéro d'édition2

- Nombre de pages288

- Coordonnées du fabricantnon disponible

EUR 27,11 expédition depuis Etats-Unis vers France

Destinations, frais et délaisRésultats de recherche pour India: In Word and Image, Revised, Expanded and Updated:...

India: in Word and Image, Revised, Expanded and Updated : In Word and Image

Vendeur : Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, Etats-Unis

Etat : Very Good. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. N° de réf. du vendeur 48968126-75

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

India: In Word & Image

Vendeur : ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, Etats-Unis

Hardcover. Etat : Fair. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 5.45. N° de réf. du vendeur G1599621282I5N01

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

India: In Word and Image, Revised, Expanded and Updated: In Word and Image

Vendeur : Goodwill of Greater Milwaukee and Chicago, Racine, WI, Etats-Unis

Etat : acceptable. Book is considered to be in acceptable condition. The actual cover image may not match the stock photo. Book may have one or more of the following defects: noticeable wear on the cover dust jacket or spine; curved, dog eared or creased page s ; writing or highlighting inside or on the edges; sticker s or other adhesive on cover; CD DVD may not be included; and book may be a former library copy. N° de réf. du vendeur SEWV.1599621282.A

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

India: In Word and Image, Revised, Expanded and Updated: In Word and Image

Vendeur : Friends of Johnson County Library, Lenexa, KS, Etats-Unis

hardcover. Etat : Good. Ex-library hardcover with stickers and labels but otherwise appears only lightly used. The dust jacket is protected with a mylar covering. The pages appear to be clean and unmarked. All items ship Monday - Saturday - Fast Shipping in a secure package. Your purchase will help support the programs and collections of the Johnson County (Kansas) Library. N° de réf. du vendeur 53DTEE0009HC

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

India: In Word and Image, Revised, Expanded and Updated: In Word and Image

Vendeur : Pink Casa Antiques, Frankfort, KY, Etats-Unis

hardcover. Etat : Very Good. 2nd ed. hardcover with dust jacket, tight, pages clear and bright, shelf and edge wear, corners bumped, packaged in cardboard box for shipment, tracking on U.S. orders. N° de réf. du vendeur 100849OS

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

India: In Word and Image, Revised, Expanded and Updated: In Word and Image

Vendeur : Vive Liber Books, Somers, CT, Etats-Unis

Etat : good. Pages are clean with normal wear. May have limited markings & or highlighting within pages & or cover. May have some wear & creases on the cover. The spine may also have minor wear. May not include CD DVD, access code or any other supplemental materials. N° de réf. du vendeur VLM.SEH

Quantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)