letter editor nature quantum mechanical de bohr niels (1 résultats)

CommentairesFiltres de recherche

Type d'article

- Tous les types de produits

- Livres (1)

- Magazines & Périodiques (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Bandes dessinées (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Partitions de musique (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Art, Affiches et Gravures (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Photographies (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Cartes (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Manuscrits & Papiers anciens (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

Etat En savoir plus

- Neuf (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Comme neuf, Très bon ou Bon (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Assez bon ou satisfaisant (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Moyen ou mauvais (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Conformément à la description (1)

Reliure

- Toutes

- Couverture rigide (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Couverture souple (1)

Particularités

- Ed. originale (1)

- Signé (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Jaquette (1)

- Avec images (1)

- Sans impressions à la demande (1)

Langue (1)

Prix

- Tous les prix

- Moins de EUR 20 (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- EUR 20 à EUR 45 (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

- Plus de EUR 45

Livraison gratuite

- Livraison gratuite à destination de Etats-Unis (Aucun autre résultat ne correspond à ces critères)

Pays

Evaluation du vendeur

-

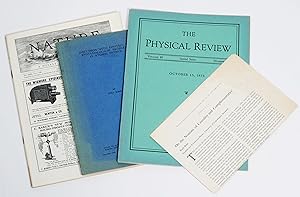

Letter to the Editor of Nature (13 July, 1935); "Can the Quantum Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete?", in Physical Review (1935); "Discussion with Einstein on Epistemological Problems in Atomic Physics", offprint from Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist (1949); "On Notions of Causality and Complementarity", offprint from Science (1950)

Date d'édition : 1950

Vendeur : Manhattan Rare Book Company, ABAA, ILAB, New York, NY, Etats-Unis

Edition originale

EUR 5 910,20

Autre deviseEUR 5,10 expédition vers Etats-UnisQuantité disponible : 1 disponible(s)

Ajouter au panierOriginal wrappers. Etat de la jaquette : Very Good. First edition. IMPORTANT PAPERS BY NIELS BOHR CONCERNING HIS DEBATES WITH ALBERT EINSTEIN OVER FOUNDATIONAL ISSUES IN QUANTUM MECHANICS. From the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s, at scientific conferences, in published papers and in informal discussions, two of the greatest physicists of their generation-Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr-argued about the emerging theory of quantum mechanics. Quantum theory had been phenomenally successful in explaining experimental results that had puzzled physicists for decades, and in accurately predicting new results. No one denied its predictive power, least of all Einstein who had been one of the early pioneers of the theory. However, the interpretation of the theory-the elucidation of its relationship to some (presumably) underlying physical reality-was a different matter. Quantum theory predicted only the probabilities of various experimental outcomes. Of course, probabilistic (or statistical) models of nature were nothing new to physicists. In the nineteenth century, Ludwig Boltzmann and others had developed the theory of statistical mechanics, which was concerned with predicting the bulk thermodynamic properties of materials through a statistical analysis of the motions of large ensembles of molecules, without attempting the impossible task of measuring or predicting the motion of each individual molecule. In statistical mechanics, the results were understood to be mere summaries of a more detailed underlying reality that was, as a practical matter, inaccessible to experimental observation. The question raised by quantum theory was whether its predictions merely reflected an incomplete knowledge of the underlying physical systems, as with statistical mechanics, or whether quantum systems were statistical (or probabilistic) in a more fundamental and ontological sense. Put another way, was the underlying reality itself probabilistic, or were there "hidden variables"-like the motions of individual molecules in statistical mechanics-which, even if not experimentally accessible, explained the rules of the theory? Bohr advanced the former view, and made it one of the fundamental pillars of the so-called "Copenhagen interpretation" of quantum theory that is associated with him and his followers. Initially, Einstein seemed willing to accept some elements of what later became solidified as the Copenhagen interpretation. "In 1905 Einstein had proposed that under certain circumstances monochromatic light [.] behaves as if it consists of light quanta, photons, particle-like objects" (Pais, p. 230). In trying to reconcile his proposal with the traditional wave theory of light, Einstein, in a 1909 paper, stated, "Deshalb ist es meine Meinung, daß die nächste Phase der Entwicklung der theoretischen Physik uns eine Theorie des Lichtes bringen wird, welche sich als eine Art Verschmelzung von Undulations- und Emissionstheorie des Lichtes auffassen läßt." [Therefore it is my opinion that the next phase of in the development of theoretical physics will bring us a theory of light that can be understood as a sort of fusion of the wave and particle theories light.] (Einstein, p. 817). Such a "profound statement", writes Bohr's assistant and later college of Einstein's, Abraham Pais, "foreshadows the fusion achieved in quantum mechanics-the new mechanics so offensive to Einstein's later views." (Pais, p. 231). But when physicists began to take sides on Bohr's emerging theory of complementarity, Einstein joined Schrödinger, Planck and others who were unable to accept the view of the natural world that was implicit in the Copenhagen interpretation. (Schrödinger's best-known contribution to the debate was his famous "Schrödinger's cat" thought experiment. Heisenberg, on the other hand, sided with Bohr.) These disputes became a focus of the Fifth Solvay Conference on Physics, held in Brussels in 1927. "All the creators of both the old and the new quantum theory were in attendance. The general discussion was opened by the venerable Lorentz, president of the meeting, who asked: 'Could one not maintain determinism by making it an article of faith? Must one necessarily elevate indeterminism to a principle?'" (Pais, 425-26). "[Einstein's] reservations [concerning quantum theory] were twofold. Firstly, he felt the theory had abdicated the historical task of natural science to provide knowledge of significant aspects of nature that are independent of observers or their observations. Instead the fundamental understanding of the quantum wave function [.] was that it only treated the outcomes of measurements (via probabilities given by the Born Rule). The theory was simply silent about what, if anything, was likely to be true in the absence of observation. That there could be laws, even probabilistic laws, for finding things if one looks, but no laws of any sort for how things are independently of whether one looks, marked quantum theory as irrealist. Secondly, the quantum theory was essentially statistical. The probabilities built into the state function were fundamental and, unlike the situation in classical statistical mechanics, they were not understood as arising from ignorance of fine details. In this sense the theory was indeterministic. Thus Einstein began to probe how strongly the quantum theory was tied to irrealism and indeterminism." (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). As Einstein saw it, the only way to preserve realism and determinism was to assume that quantum theory, successful as it was empirically, was not a "complete" theory of nature, and that there must be hidden variables affecting the experimental outcomes that would have to be included in any complete theory (even if they were not experimentally observable). The two pairs of papers offered here provide important documentation, from Bohr's perspective, of the Bohr-Einstein debate. I. Bohr's Reaction to the EPR Paper-Letter to the Editor of Nature (July 13, 1935) and "Can the Quantum Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be C.